Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University Southeast Asian Studies, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

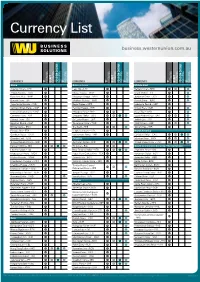

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

Treasury Reporting Rates of Exchange. As of March 31, 1979

^ J ;; u LIBRARY :' -'"- • 5-J 5 4 TREASURY REPORTING RATES OF EXCHANGE. AS OF MARCH 31, 1979 (/.S. DEPARIMENX-OF^JHE. TREASURY Fiscal Service Bureau of Government Financial Operations FOREWORD This report is prepared to promulgate exchange rate information pursuant to Section 613 of P.L. 87-195 dated September 4, 1961 (22 USC 2363(b)) which grants the Secretary of the Treasury "sole authority to establish for all foreign currencies or credits the exchange rates at which such currencies are to be reported by all agencies of the Government." The primary purpose of- this report is to insure that foreign currency reports prepared by agencies shall be consistent with regularly published Treasury foreign currency reports as to amounts stated in foreign currency units and U.S. dollar equivalents. This includes all foreign currencies in which the U.S. Government has an interest, including receipts and disbursements, accrued revenues and expenditures, authorizations, obligations, receivables and payables, refunds, and similar reverse transaction items. Exceptions to using the reporting rates as shown in this report are collections and refunds to be valued at specified rates set by international agreements, conversions of one foreign currency into another, foreign currencies sold for dollars and other types of transactions affecting dollar appropriations. See Chapter I Treasury Fiscal Requirements Manual 2-3200 for further details. This quarterly report reflects exchange rates at which foreign currencies can be acquired by the U.S. Government for official expenditures as reported by Disbursing Officers for each post on the last business day of the month prior to the date of the published report. -

CAMBODIA Griculture T T Extiles Ourism

CAPITAL: PHNOM PENH Pehn CAMBODIA LANGUAGES POPULATION OF KHMER 16.9 MILLION 181,035 SQ KM IN LAND AREA 47% OF POPULATION FAVOURITE SPORTS: ARE UNDER SOCCER 24 YEARS OLD MARTIAL ARTS SEPAK TAKRAW 97.9% (SIMILAR TO VOLLEYBALL) CAMBODIAN RIEL BUDDHIST MAJOR INDUSTRIES: RELIGION AGRICULTURE 1.1% ISLAM TOURISM EXTILES T 1% OTHER CAMBODIA A students spends time in the recently completed physiotherapy room at LaValla Students at LaValla school help to prepare food for a meal. The Cambodian proverb “Fear not the future, weep not for the past” captures the general approach to life in the country. Given the tragedies experienced during the Khmer Rouge regime, many have demonstrated immense forgiveness to live harmoniously with those who were a part of the regime as well as those Khmer who may Geography have lost loved ones. Cambodians also tend to have a stoic and cheerful demeanour. They rarely complain or The Kingdom of Cambodia is a Southeast Asian nation show discomfort. People often smile or laugh in various that borders Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam. Cambodia scenarios, regardless of whether the situation is positive has a tropical climate and experiences a monsoon or negative. season (May to November) and a dry season (December to April). The terrain is mostly low, flat plains, with AMS Projects in Cambodia – LaValla mountains in the southwest and north. The Lavalla Project, a work of Marist Solidarity Cambodia, History provides formal and inclusive education for children and young people with disabilities. As well the students have For 2,000 years Cambodia’s civilization was influenced by access to a comprehensive health and rehabilitation India and China - it also contributed significantly to these programme. -

Treasury Reporting Rates of Exchange As of March 31, 1978

TREASURY REPORTING RATES OF EXCHANGE AS OF MARCH 31, 1978 DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY Fiscal Service Bureau of Government Financial Operations FOREWORD This report is prepared to promulgate exchange rate information pursuant to Section 613 of P.L. 87-195 dated September 4, 1961 (22 USC 2363(b)) which grants the Secretary of the Treasury "sole authority to establish for all foreign currencies or credits the exchange rates at which such currencies are to be reported by all agencies of the Government." The primary purpose of this report is to insure that foreign currency reports prepared by agencies shall be consistent with regularly published Treasury foreign currency reports as to amounts stated in foreign currency units and U.S. dollar equivalents. This includes all foreign currencies in which the U.S. Government has an interest, including receipts and disbursements, accrued revenues and expenditures, authorizations, obligations, receivables and payables, refunds, and similar reverse transaction items. Exceptions to using the reporting rates as shown in this report are collections and refunds to be valued at specified rates set by international agreements, conversions of one foreign currency into another, foreign currencies sold for dollars and other types of transactions affecting dollar appropriations. See Treasury Circular No, 930, Section 4a (3) of Procedures Memorandum No. 1 for further details. This quarterly report reflects exchange rates at which foreign currencies can be acquired by the U.S. Government for official expenditures as reported by Disbursing Officers for each post on the last business day of the month prior to the date of the published report. -

Cambodia Economic Update

Public Disclosure Authorized REAL GDP GROWTH TOURIST ARRIVALS (Y/Y % Public Disclosure Authorized 12 30 RIGHT SCALE) 10 20 GARMENT EXPORTS (Y/Y % CHANGE, RIGHT SCALE) 8 10 6 0 4 -10 Public Disclosure Authorized 2 0 -20 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 THE WORLD BANK Public Disclosure Authorized SEPTEMBER 2013 RESILIENCE AMIDST A CHALLENGING ENVIRONMENT CAMBODIA ECONOMIC UPDATE SEPTEMBER 2013 @ All rights reserved This Cambodia Economic Update is a product of the World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in the Update are those of World Bank staff, and do not necessarily reflect the views of its management, Executive Board, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Cambodia Economic Update is a product of the staff of the World Bank. It was prepared by Sodeth Ly, and reviewed and edited by Enrique Aldaz-Carroll, Poverty Reduction and Economic Management (PREM) Sector Department, Cambodia Country Office, the World Bank. The Poverty Team, led by Samsen Neak, contributed the poverty section for the Update. The team worked under the guidance of Mathew A. Verghis, Lead Economist and Sector Manager, PREM Sector Department, and Alassane Sow, Country Manager for Cambodia. The Update is produced bi-annually to provide up-to-date information on macroeconomic developments in Cambodia. The Update is published and distributed widely to the Cambodian authorities, the development partner community, the private sector, think tanks, civil society organizations, non-government organizations, and academia. -

The Mekong Region 27% Viet Nam JPY 34.4 Billion Laos Loans: % Preparing for the 64 Next Stage of Growth Technical 2019 Is Mekong-Japan Exchange Year

P. 4 - 7 Technical Grants: 2% Cooperation: 6% Human Resource Development for Industry Technical Cooperation: 22% Laos Grants: Viet Nam Official Name: Lao People’s 41% JPY Official Name: Socialist Republic Democratic Republic of Viet Nam JPY 10.4 billion Capital: Hanoi Capital: Vientiane billion Myanmar Currency: Lao Kip Currency: Vietnamese Dong 114.7 Population: 6.49 million Population: 93.7 million Official Name: Republic of the (General Statistics Union of Myanmar (Lao Statistics Bureau, Loans: % 2015) 37 Office of Viet Nam, 2017) Capital: Naypyidaw Official Language: Vietnamese Currency: Burmese Kyat Official Language: Lao Loans: 92% Population: 51.41 million (Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population, Sept. 2014) Official Language: Burmese Grants: 9% Technical Feature Cooperation: Myanmar The Mekong Region 27% Viet Nam JPY 34.4 billion Laos Loans: % Preparing for the 64 Next Stage of Growth Technical 2019 is Mekong-Japan Exchange Year. For many years, Japan has been working together with countries of the Cooperation: 9% Mekong region to enhance development by means of training personnel and improving the region’s industrial and Thailand socioeconomic foundation. Japan has helped set the basis for significant growth in the region through its efforts to develop economic corridors linking people in the Mekong countries. Matching the need for increased connectivity within the region, we trace Japan’s efforts to help overcome the problems faced by each of the countries—from JPY developing business personnel and improving logistics, to coordinating with Thailand, the forerunner in the region, 30.1billion Thailand to contribute to development of the other Mekong countries. Official Name: Kingdom of Cambodia Pie Graphs: Amount of JICA assistance in the Mekong Region (FY2017) Thailand Capital: Bangkok Technical Cooperation Loans Grants *The figure in the center of the pie graph indicates the total amount. -

Cambodia Country Report BTI 2016

BTI 2016 | Cambodia Country Report Status Index 1-10 4.12 # 104 of 129 Political Transformation 1-10 3.73 # 98 of 129 Economic Transformation 1-10 4.50 # 96 of 129 Management Index 1-10 3.42 # 111 of 129 scale score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2016. It covers the period from 1 February 2013 to 31 January 2015. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2016 — Cambodia Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2016. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. BTI 2016 | Cambodia 2 Key Indicators Population M 15.3 HDI 0.584 GDP p.c., PPP $ 3259.3 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 1.6 HDI rank of 187 136 Gini Index 30.8 Life expectancy years 71.7 UN Education Index 0.495 Poverty3 % 37.0 Urban population % 20.5 Gender inequality2 0.505 Aid per capita $ 53.4 Sources (as of October 2015): The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2015 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2014. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $3.10 a day at 2011 international prices. Executive Summary The outcome of Cambodia’s parliamentary elections in July 2013 was much closer than expected. Although the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) used various instruments to reduce the competitive character of the election, it lost more than 9% points and garnered just 48.8% of the vote, while the fledgling Cambodian National Rescue Party (CNRP) – founded in 2012 through the merger of two liberal opposition parties, the Sam Rainsy Party and the Human Rights Party – garnered 44.5% of the vote. -

42361-013: Medium-Voltage Sub-Transmission Expansion

Initial Environmental Examination November 2014 CAM: Medium-Voltage Sub-Transmission Expansion Sector Project (Package 2) Subproject 1: Kampong Thom Province (extension) Subproject 3: Siem Reap Province (extension) Subproject 4: Kandal Province Subproject 5: Banteay Meanchey Province Prepared by Electricité du Cambodge, Royal Government of Cambodia for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Official exchange rate of the National Bank of Cambodia as of 24 November 2014) Currency unit – Cambodian Riel (KHR) KHR1.00 = $0.000246 $1.00 = KHR 4,063 ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank AP Affected person APSARA Authority for the Protection and Management of Angkor and the Region of Siem Reap CEMP Construction Environmental Management Plan CMAA Cambodian Mine Action and Victim Assistance Authority DCFA Department of Culture and Fine Arts DMC Developing member country DoE Department of Environment EA Executing Agency EAC Electricity Authority of Cambodia EARF Environmental Assessment and Review Framework EDC Electricité du Cambodge EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EMoP Environmental Monitoring Plan EMP Environmental Management Plan GRM Grievance Redress Mechanism IA Implementing agency IBA Important Bird Area IEC International Electrotechnical Commission IEE Initial Environmental Examination IEIA Initial Environmental Impact Assessment IFC International Finance Corporation IUCN International Union for Conservation of Nature LV Low voltage MARPOL Marine Pollution Convention MCFA Ministry of Culture and -

Read the Volunteer Handbook

Som Swa Kom! Welcome to Cambodia! Welcome to Cambodia! I am very grateful for your interest and initiative in wanting to come to Cambodia, not only to enjoy the scenery and culture but also to work with Habitat for Humanity in Cambodia. I hope that you benefit from this trip as you immerse yourself building houses with our partner families and volunteers. Joining a short-term Global Village trip will be one of the most challenging and rewarding experiences of your life. It may feel like an overwhelming responsibility, and at times it will be. But most of our Global Village volunteers find that the excitement, the sense of accomplishment, and the joy they give and receive are all well worth the work. As important, this experience also benefits our partner families by broadening their relations with foreign cultures and people. We fully expect that your stay in the country will build friendships as well as homes. You will find that living, working and associating with the local community is the core experience- the focus is on teamwork and partnership. Come to Cambodia with an open mind and with broad expectations. You will find that plans often unfold in ways you might not expect, but usually in ways that make the trip even more meaningful and the experience more fulfilling. We will do our best to ensure that you learn, grow and perhaps even be transformed while you build and help provide homes for deserving families in need. Kif Nguyen National Director Habitat for Humanity Cambodia CAMBODIA Country Profile Population and Location THE KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA occupies a land area of 181, 035 square kilometers and is located in the heart of Southeast Asia. -

Cambodia Sustaining Strong Growth for the Benefit of All a Systematic Country Diagnostic Public Disclosure Authorized

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized CAMBODIA SUSTAINING STRONG GROWTH FOR THE BENEFIT OF ALL A Systematic Country Diagnostic Public Disclosure Authorized Report No. 115189-KH This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Attribution Please cite the work as follows: World Bank. 2017. Cambodia - Sustaining strong growth for the benefit of all. Washington, D.C. : World Bank Group. https://hubs.worldbank.org/docs/imagebank/pages/docprofile.aspx?nodeid=27520556 Rights and permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. -

ANNEX a to the 1998 FX and CURRENCY OPTION DEFINITIONS AMENDED and RESTATED AS of NOVEMBER 19, 2017 I

ANNEX A to the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions _________________________ Amended and Restated November 19, 2017 Amended March 16, 2020 INTERNATIONAL SWAPS AND DERIVATIVES ASSOCIATION, INC. EMTA, INC. TRADE ASSOCIATION FOR THE EMERGING MARKETS Copyright © 2000-2020 by INTERNATIONAL SWAPS AND DERIVATIVES ASSOCIATION, INC. EMTA, INC. ISDA and EMTA consent to the use and photocopying of this document for the preparation of agreements with respect to derivative transactions and for research and educational purposes. ISDA and EMTA do not, however, consent to the reproduction of this document for purposes of sale. For any inquiries with regard to this document, please contact: INTERNATIONAL SWAPS AND DERIVATIVES ASSOCIATION, INC. 10 East 53rd Street New York, NY 10022 www.isda.org EMTA, Inc. 405 Lexington Avenue, Suite 5304 New York, N.Y. 10174 www.emta.org TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION TO ANNEX A TO THE 1998 FX AND CURRENCY OPTION DEFINITIONS AMENDED AND RESTATED AS OF NOVEMBER 19, 2017 i ANNEX A CALCULATION OF RATES FOR CERTAIN SETTLEMENT RATE OPTIONS SECTION 4.3. Currencies 1 SECTION 4.4. Principal Financial Centers 6 SECTION 4.5. Settlement Rate Options 9 A. Emerging Currency Pair Single Rate Source Definitions 9 B. Non-Emerging Currency Pair Rate Source Definitions 21 C. General 22 SECTION 4.6. Certain Definitions Relating to Settlement Rate Options 23 SECTION 4.7. Corrections to Published and Displayed Rates 24 INTRODUCTION TO ANNEX A TO THE 1998 FX AND CURRENCY OPTION DEFINITIONS AMENDED AND RESTATED AS OF NOVEMBER 19, 2017 Annex A to the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions ("Annex A"), originally published in 1998, restated in 2000 and amended and restated as of the date hereof, is intended for use in conjunction with the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions, as amended and updated from time to time (the "FX Definitions") in confirmations of individual transactions governed by (i) the 1992 ISDA Master Agreement and the 2002 ISDA Master Agreement published by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association, Inc. -

The Economic Consequences of Civil War in Asia: a Comparison of Sri Lanka and Cambodia

78 The Economic Consequences of Civil War in Asia: A comparison of Sri Lanka and Cambodia Simon CAREY* Abstract This study looks into the nature of two prominent Asian civil wars and the impacts they had on their respective economies. Comparing the 1967-1979 Khmer Rouge genocides in Cambodia with the more recent 1983-2009 Sri Lankan war for Tamil independence, we look specifically at the impacts on infrastructure and land, the fiscal system, and the monetary and financial systems. Evidence suggests that the Cambodian civil war fits the standard mould for internally worn-torn countries, while the relatively more isolated nature of the Sri Lankan conflict led to significantly different outcomes. It is still too soon to compare the post-conflict impacts on the two nations, however. *[email protected] Essay submitted towards FIN1234 SJEF Vol 1 (2011) No 1 79 1 Introduction and Brief Literature Review For any country, engaging in conflict comes with significant cost. However, for countries engaged in domestic conflicts the costs are often particularly high (Collier, 1999). Violence and social upheaval drastically alter the lives of those living in afflicted areas and take their toll via a number of economic impacts. This study looks at these economic impacts in two Asian countries – Cambodia and Sri Lanka. These two countries make an interesting comparison because although they are in a similar part of the world they experienced distinctly different civil wars, as we shall discuss below. This study will compare the experiences of each country and the similarities and differences between them and other civil wars more generally.