Cambodia Country Report BTI 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University Southeast Asian Studies, Vol

https://englishkyoto-seas.org/ Shimojo Hisashi Local Politics in the Migration between Vietnam and Cambodia: Mobility in a Multiethnic Society in the Mekong Delta since 1975 Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 10, No. 1, April 2021, pp. 89-118. How to Cite: Shimojo, Hisashi. Local Politics in the Migration between Vietnam and Cambodia: Mobility in a Multiethnic Society in the Mekong Delta since 1975. Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 10, No. 1, April 2021, pp. 89-118. Link to this article: https://englishkyoto-seas.org/2021/04/vol-10-no-1-shimojo-hisashi/ View the table of contents for this issue: https://englishkyoto-seas.org/2021/04/vol-10-no-1-of-southeast-asian-studies/ Subscriptions: https://englishkyoto-seas.org/mailing-list/ For permissions, please send an e-mail to: english-editorial[at]cseas.kyoto-u.ac.jp Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 49, No. 2, September 2011 Local Politics in the Migration between Vietnam and Cambodia: Mobility in a Multiethnic Society in the Mekong Delta since 1975 Shimojo Hisashi* This paper examines the history of cross-border migration by (primarily) Khmer residents of Vietnam’s Mekong Delta since 1975. Using a multiethnic village as an example case, it follows the changes in migratory patterns and control of cross- border migration by the Vietnamese state, from the collectivization era to the early Đổi Mới reforms and into the post-Cold War era. In so doing, it demonstrates that while negotiations between border crossers and the state around the social accep- tance (“licit-ness”) and illegality of cross-border migration were invisible during the 1980s and 1990s, they have come to the fore since the 2000s. -

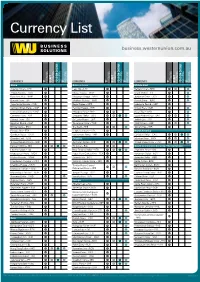

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: an Ambiguous Good News Story

perspectives The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: An Ambiguous Good News Story Milton Osborne A u g u s t 2 0 0 7 The Lowy Institute for International Policy is an independent international policy think tank based in Sydney, Australia. Its mandate ranges across all the dimensions of international policy debate in Australia – economic, political and strategic – and it is not limited to a particular geographic region. Its two core tasks are to: • produce distinctive research and fresh policy options for Australia’s international policy and to contribute to the wider international debate. • promote discussion of Australia’s role in the world by providing an accessible and high quality forum for discussion of Australian international relations through debates, seminars, lectures, dialogues and conferences. Lowy Institute Perspectives are occasional papers and speeches on international events and policy. The views expressed in this paper are the author’s own and not those of the Lowy Institute for International Policy. The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: an ambiguous good news story Milton Osborne It’s [the Khmer Rouge Tribunal] heavily symbolic and won’t have much to do with justice . It will produce verdicts which delineate the KR leadership as having been a small group and nothing to do with the present regime. Philip Short, author of Pol Pot: anatomy of a nightmare, London, 2004, quoted in Phnom Penh Post, 26 January8 February 2007. Some ten months after it was finally inaugurated in July 2006, and more than twentyeight years after the overthrow of the Democratic Kampuchean (DK) regime led by Pol Pot, the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), more familiarly known as the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, has at last handed down its first indictment. -

Treasury Reporting Rates of Exchange. As of March 31, 1979

^ J ;; u LIBRARY :' -'"- • 5-J 5 4 TREASURY REPORTING RATES OF EXCHANGE. AS OF MARCH 31, 1979 (/.S. DEPARIMENX-OF^JHE. TREASURY Fiscal Service Bureau of Government Financial Operations FOREWORD This report is prepared to promulgate exchange rate information pursuant to Section 613 of P.L. 87-195 dated September 4, 1961 (22 USC 2363(b)) which grants the Secretary of the Treasury "sole authority to establish for all foreign currencies or credits the exchange rates at which such currencies are to be reported by all agencies of the Government." The primary purpose of- this report is to insure that foreign currency reports prepared by agencies shall be consistent with regularly published Treasury foreign currency reports as to amounts stated in foreign currency units and U.S. dollar equivalents. This includes all foreign currencies in which the U.S. Government has an interest, including receipts and disbursements, accrued revenues and expenditures, authorizations, obligations, receivables and payables, refunds, and similar reverse transaction items. Exceptions to using the reporting rates as shown in this report are collections and refunds to be valued at specified rates set by international agreements, conversions of one foreign currency into another, foreign currencies sold for dollars and other types of transactions affecting dollar appropriations. See Chapter I Treasury Fiscal Requirements Manual 2-3200 for further details. This quarterly report reflects exchange rates at which foreign currencies can be acquired by the U.S. Government for official expenditures as reported by Disbursing Officers for each post on the last business day of the month prior to the date of the published report. -

Microsoft Office 2000

mCÄmNÐlÉkßrkm<úCa Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) Genocide Education is Genocide Prevention Education on Democratic Kampuchea History in Cambodia (1975-1979) Report 28th Classroom forum on "the importance of studying the Khmer Rouge history (1975-1979) at Bun Rany Hun Sen Koh Dach High School Report by: Seang Chenda January 23, 2018 Documentation Center of Cambodia (constituted in 1995) Searching for the Truth: Memory & Justice EsVgrkKrBit edIm, IK rcg©M nig yutþiFm‘’ 66 Preah Sihanouk Blvd. P.O.Box 1110 Phnom Penh Cambodia t (855-23) 211-875 [email protected] www.dccam.org Table of Content Overall Summary ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Purpose of the forum .................................................................................................................................... 4 Forum ................................................................................................................................................................. 5 1 Opening remark ...................................................................................................................................... 5 2 Pre-forum survey and K-W-L chart ................................................................................................. 5 3 Documentary film screening .............................................................................................................. 5 4 Presentation of DK history and -

07 Raimund Weiß 3교OK.Indd

Asian Journal of Peacebuilding Vol. 8 No. 1 (2020): 113-131 doi: 10.18588/202005.00a069 Research Article Peacebuilding, Democratization, and Political Reconciliation in Cambodia Raimund Weiß This research article explains why Cambodia’s dual transition of peacebuilding and democratization after the civil war led to peace but not democracy. The research finds that democratization often threatened peacebuilding in Cambodia. Particularly elections led to political instability, mass protests, and renewed violence, and thus also blocked reforms to democratize Cambodia’s government institutions. By applying the war-to-democracy transition theory and theories of political reconciliation to Cambodia’s dual transition, the following research article finds that a lack of political reconciliation between Cambodia’s former civil war parties is the main reason why the dual transition failed. This article argues that peace-building and democratization are only complementary processes in post-civil war states when preceded by political reconciliation between the former civil war parties. Keywords Cambodia, dual transition, peacebuilding, democratization, war-to-democracy transition theory Introduction The year 2020 marks almost thirty years of peacebuilding in Cambodia. The country appears to have overcome the violence and destruction of two civil wars and the totalitarian Pol Pot regime. Cambodia experiences the longest-lasting peace since gaining independence from France in 1953. But despite this progress, peacebuilding in Cambodia did not lead to the consolidation of liberal multiparty democracy as foreseen in the Paris Peace Accords. In July 2018, Cambodia held the sixth national election since the end of the civil war. The incumbent Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) under Prime Minister Hun Sen won for the first time all 125 seats of Cambodia’s National Assembly. -

Perspectives

perspectives The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: An Ambiguous Good News Story Milton Osborne A u g u s t 2 0 0 7 The Lowy Institute for International Policy is an independent international policy think tank based in Sydney, Australia. Its mandate ranges across all the dimensions of international policy debate in Australia – economic, political and strategic – and it is not limited to a particular geographic region. Its two core tasks are to: • produce distinctive research and fresh policy options for Australia’s international policy and to contribute to the wider international debate. • promote discussion of Australia’s role in the world by providing an accessible and high quality forum for discussion of Australian international relations through debates, seminars, lectures, dialogues and conferences. Lowy Institute Perspectives are occasional papers and speeches on international events and policy. The views expressed in this paper are the author’s own and not those of the Lowy Institute for International Policy. The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: an ambiguous good news story Milton Osborne It’s [the Khmer Rouge Tribunal] heavily symbolic and won’t have much to do with justice . It will produce verdicts which delineate the KR leadership as having been a small group and nothing to do with the present regime. Philip Short, author of Pol Pot: anatomy of a nightmare, London, 2004, quoted in Phnom Penh Post, 26 January8 February 2007. Some ten months after it was finally inaugurated in July 2006, and more than twentyeight years after the overthrow of the Democratic Kampuchean (DK) regime led by Pol Pot, the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), more familiarly known as the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, has at last handed down its first indictment. -

Cambodia's Appeal for International Conference on Border Issue With

YEAR: 3 NO:31 BULLETIN: JULY - AUG UST, 2010 CONTENT : PAGE 1 - Cambodia’s Appeal for Inter- national Conference on Bor- der Issue with Thailand. Cambodia’s Appeal for International Page 1 Conference on Border Issue with Thailand - PM: Cambodia’s Economic Growth Will Be at 5 Percent. Page 1 sent letters to mier while presiding - Cambodian Premier Presides UN General over the dissemina- Over the Closing of the 5th A s s e m b l y tion ceremony of the CRC General Assembly. President Ali National Program for Page 2 Abdussalam Sub-national Democ- Treki and UN ratic Development - Cambodia, Iran Agree to S e c u r i t y held here on Aug. 9 Boost Ties. Page 2 Council Presi- at Koh Pich confer- dent Vitaly ence center. - Statement of the Ministry of Churkin com- “The bilateral Foreign Affairs and Interna- plaining about mechanism would tional Cooperation. Page 3 Thailand’s not work anymore. threat to use We need to resort to Prime Minister Samdech Akka Moha Sena Padei Techo Hun Sen both diplo- multilateral mecha- - World Heritage Committee addresses the audiences over the launching ceremony of the (WHC) Supports UNESCO National Program for Sub-National Democratic Development matic and nism. We call upon to Work with Cambodia over (2010-2019) military means the ASEAN member Conservation of Preah- to resolve the countries, the UN Vihear. Page 3 border dispute and other countries Phnom Penh, August dia, has called for an with Cambodia. including the country - Cambodian Garment Industry 10, 2010 AKP — international confer- “I am appealing members of the Paris More Competitive, Experts Samdech Akka ence on Cambodia- to hold an interna- Peace Accords,” he Say. -

CAMBODIA Griculture T T Extiles Ourism

CAPITAL: PHNOM PENH Pehn CAMBODIA LANGUAGES POPULATION OF KHMER 16.9 MILLION 181,035 SQ KM IN LAND AREA 47% OF POPULATION FAVOURITE SPORTS: ARE UNDER SOCCER 24 YEARS OLD MARTIAL ARTS SEPAK TAKRAW 97.9% (SIMILAR TO VOLLEYBALL) CAMBODIAN RIEL BUDDHIST MAJOR INDUSTRIES: RELIGION AGRICULTURE 1.1% ISLAM TOURISM EXTILES T 1% OTHER CAMBODIA A students spends time in the recently completed physiotherapy room at LaValla Students at LaValla school help to prepare food for a meal. The Cambodian proverb “Fear not the future, weep not for the past” captures the general approach to life in the country. Given the tragedies experienced during the Khmer Rouge regime, many have demonstrated immense forgiveness to live harmoniously with those who were a part of the regime as well as those Khmer who may Geography have lost loved ones. Cambodians also tend to have a stoic and cheerful demeanour. They rarely complain or The Kingdom of Cambodia is a Southeast Asian nation show discomfort. People often smile or laugh in various that borders Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam. Cambodia scenarios, regardless of whether the situation is positive has a tropical climate and experiences a monsoon or negative. season (May to November) and a dry season (December to April). The terrain is mostly low, flat plains, with AMS Projects in Cambodia – LaValla mountains in the southwest and north. The Lavalla Project, a work of Marist Solidarity Cambodia, History provides formal and inclusive education for children and young people with disabilities. As well the students have For 2,000 years Cambodia’s civilization was influenced by access to a comprehensive health and rehabilitation India and China - it also contributed significantly to these programme. -

Treasury Reporting Rates of Exchange As of March 31, 1978

TREASURY REPORTING RATES OF EXCHANGE AS OF MARCH 31, 1978 DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY Fiscal Service Bureau of Government Financial Operations FOREWORD This report is prepared to promulgate exchange rate information pursuant to Section 613 of P.L. 87-195 dated September 4, 1961 (22 USC 2363(b)) which grants the Secretary of the Treasury "sole authority to establish for all foreign currencies or credits the exchange rates at which such currencies are to be reported by all agencies of the Government." The primary purpose of this report is to insure that foreign currency reports prepared by agencies shall be consistent with regularly published Treasury foreign currency reports as to amounts stated in foreign currency units and U.S. dollar equivalents. This includes all foreign currencies in which the U.S. Government has an interest, including receipts and disbursements, accrued revenues and expenditures, authorizations, obligations, receivables and payables, refunds, and similar reverse transaction items. Exceptions to using the reporting rates as shown in this report are collections and refunds to be valued at specified rates set by international agreements, conversions of one foreign currency into another, foreign currencies sold for dollars and other types of transactions affecting dollar appropriations. See Treasury Circular No, 930, Section 4a (3) of Procedures Memorandum No. 1 for further details. This quarterly report reflects exchange rates at which foreign currencies can be acquired by the U.S. Government for official expenditures as reported by Disbursing Officers for each post on the last business day of the month prior to the date of the published report. -

Women in Cambodia – Analysing the Role and Influence of Women in Rural Cambodian Society with a Special Focus on Forming Religious Identity

WOMEN IN CAMBODIA – ANALYSING THE ROLE AND INFLUENCE OF WOMEN IN RURAL CAMBODIAN SOCIETY WITH A SPECIAL FOCUS ON FORMING RELIGIOUS IDENTITY by URSULA WEKEMANN submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF THEOLOGY in the subject MISSIOLOGY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: DR D C SOMMER CO-SUPERVISOR: PROF R W NEL FEBRUARY 2016 1 ABSTRACT This study analyses the role and influence of rural Khmer women on their families and society, focusing on their formation of religious identity. Based on literature research, the role and influence of Khmer women is examined from the perspectives of history, the belief systems that shape Cambodian culture and thinking, and Cambodian social structure. The findings show that although very few Cambodian women are in high leadership positions, they do have considerable influence, particularly within the household and extended family. Along the lines of their natural relationships they have many opportunities to influence the formation of religious identity, through sharing their lives and faith in words and deeds with the people around them. A model based on Bible storying is proposed as a suitable strategy to strengthen the natural influence of rural Khmer women on forming religious identity and use it intentionally for the spreading of the gospel in Cambodia. KEY WORDS Women, Cambodia, rural Khmer, gender, social structure, family, religious formation, folk-Buddhism, evangelization. 2 Student number: 4899-167-8 I declare that WOMEN IN CAMBODIA – ANALYSING THE ROLE AND INFLUENCE OF WOMEN IN RURAL CAMBODIAN SOCIETY WITH A SPECIAL FOCUS ON FORMING RELIGIOUS IDENTITY is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. -

Cambodia Economic Update

Public Disclosure Authorized REAL GDP GROWTH TOURIST ARRIVALS (Y/Y % Public Disclosure Authorized 12 30 RIGHT SCALE) 10 20 GARMENT EXPORTS (Y/Y % CHANGE, RIGHT SCALE) 8 10 6 0 4 -10 Public Disclosure Authorized 2 0 -20 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 THE WORLD BANK Public Disclosure Authorized SEPTEMBER 2013 RESILIENCE AMIDST A CHALLENGING ENVIRONMENT CAMBODIA ECONOMIC UPDATE SEPTEMBER 2013 @ All rights reserved This Cambodia Economic Update is a product of the World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in the Update are those of World Bank staff, and do not necessarily reflect the views of its management, Executive Board, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Cambodia Economic Update is a product of the staff of the World Bank. It was prepared by Sodeth Ly, and reviewed and edited by Enrique Aldaz-Carroll, Poverty Reduction and Economic Management (PREM) Sector Department, Cambodia Country Office, the World Bank. The Poverty Team, led by Samsen Neak, contributed the poverty section for the Update. The team worked under the guidance of Mathew A. Verghis, Lead Economist and Sector Manager, PREM Sector Department, and Alassane Sow, Country Manager for Cambodia. The Update is produced bi-annually to provide up-to-date information on macroeconomic developments in Cambodia. The Update is published and distributed widely to the Cambodian authorities, the development partner community, the private sector, think tanks, civil society organizations, non-government organizations, and academia.