Download Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table IV-4.1.1 Summary of Small Pond Development Plan in Trapeang Snao Village, Nhaeng Nhang Commune

Table IV-4.1.1 Summary of Small Pond Development Plan in Trapeang Snao Village, Nhaeng Nhang Commune Pond Size Total Construction Member Family Proposed Condition Assets of Group Leader (m) Existing Volume Cost Pond Sub- Type Status Leader Farm Land Effective Remarks No. Village Irrigable Irrigable Electlic Trans- Land (nos.) (nos.) (m) (m) (m2) (ha) 3 Volume (US$) Cow Pig Chicken Duck Others (m ) 1st (ha) 2nd (ha) Device port (ha) (m3) 1 G R 1 Chheum Chann 5 26 20 12 240 0.51 410 256 0.10 0.05 574 4 4 40 10 Bt Bi(3) 3.00 2 I R 1 Chheum Nonn 1 7 18 17 306 0.19 567 374 0.15 0.07 789 4 2 9 15 Rd Bi 2.50 3 I R 1 Pill Toch 1 6 18 10 180 0.17 284 166 0.07 0.03 113 4 2 Bt,Tv 0.70 4 I R 1 Khorm Bross 1 4 10 23 230 0.12 366 216 0.09 0.04 404 2 1 150 0.90 5 G N 2 Ngouo Duk 5 21 16 26 416 0.95 803 544 0.22 0.10 1,491 6 40 Bt,Tv Bi(2) 3.00 buffalo(5) 6 G N 2 Minh Horn 4 19 34 17 578 0.87 1,167 812 0.32 0.15 2,165 5 10 7 Bt,Rd Bi(2),Mc(2) 4.00 7 Gc N 2 Chhum Choum 4 16 50 13 650 0.30 1,119 756 0.30 0.14 1,680 7 2 30 10 Bt,Tv,Rd Mc,Bi(3) 1.50 8 G N 2 Minh Sariun 3 9 12 20 240 0.20 410 256 0.10 0.05 763 4 2 5 20 Bt,Rd Bi(2) 2.00 9 G R 3 Tob Bunheun 5 28 16 17 272 0.75 828 567 0.23 0.10 371 2 3 7 Bt,Tv,Rd Bi(2) 1.40 10 G N 3 Soun Seun 4 19 16 21 336 0.50 630 420 0.17 0.08 1,170 11 Gc R 3 Naet Sopheap 5 20 80 11 880 0.38 1,455 959 0.38 0.17 1,499 12 G R 4 San Sariun 5 21 40 25 1000 1.00 2,244 1,631 0.65 0.30 2,678 2 10 9 Bt,Rd Mc,Bi 2.00 13 I N 7 Nop Nat 1 5 11 15 165 0.30 266 156 0.06 0.03 499 4 1 10 120 Bt,Tv Bi 0.50 14 I R 4 Prak Yorm 1 5 21 12 252 -

SBI LH AR 2020(21X18cm)

CONTENT About the Bank Financial Report About the Bank Report of the Board of Directors Key Figures Report of the Independent Auditors Page Vision, Mission and Core Values Page Statement of Financial Position Corporate Lenders 1 - 28 30 - 42 Statement of Profit or Loss and Message from Chairman Other Comprehensive Income Statement of Changes in Equity Message from CEO Statement of Cash Flows Board of Directors Senior Management Organizational Chart Risk Management Branch Networks Human Resources Standard Branch Office Products and Services Page Branches 44 - 48 About the Bank About the Bank 02 Key Figures 03 Vision, Mission and Core Values 05 Corporate Lenders 06 Message from Chairman 07 Message from CEO 09 Board of Directors 11 Senior Management 15 Organizational Chart 21 Risk Management 23 Human Resources 25 Products and Services 27 01 SBI LY HOUR Bank / Annual Report 2020 ABOUT THE BANK SBI LY HOUR Bank Plc. is a joint venture between Neak Oknha LY HOUR and SBI Holdings Inc. SBI LY HOUR Bank Plc. is a company duly incorporated under the law of the Kingdom of Cambodia. The Bank’s objective is to provide in any or all commercial SBI Holdings Inc. banking business to individuals, SMEs, companies, and corporations in general as a contribution to socio-economic 70% development in Cambodia and elsewhere as conducted by all commercial banks internationally. The aim is to help Cambodia, Cambodian businesses and people to improve the living standard and grow the business by providing highly professional, technologically advanced banking services, affordable financing and bringing the latest finan- 30% cial technology to make the user’s experience easier and Neak Oknha LY HOUR more attractive. -

Cambodia National Mekong Committee

CAMBODIA NATIONAL MEKONG COMMITTEE Basin Development Plan Programme Integrated Water Resources Management in Cambodia National Sector Review August 2003 Phnom Penh, Cambodia Cambodia National Mekong Committee National Sector Review 2003 Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES....................................................................................................................................... V ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS...................................................................................................VI FOREWORD ...........................................................................................................................................VIII PART I: ESSENTIAL ENTRODUCTORY TEXT......................................................................................I SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................. 1 SECTION 2: THE IMPORTANCE OF CROSS-SECTORAL AND BASIN WIDE LINKAGES ....... 4 2.1. Cross-Border Linkages........................................................................................4 2.2. Sector Linkages ...................................................................................................4 2.3. Planning Linkages ...............................................................................................7 SECTION 3: SUMMARIES OF THE EIGHT SECTORS....................................................................... 8 3.1. Irrigated Agriculture............................................................................................8 -

Ggácmnmucrmhvisambaøkñú

01074906 E1/273.1 ŪĮйŬď₧şŪ˝˝ņįО ď ďijЊ ⅜₤Ĝ ŪĮйņΉ˝℮Ūij GgÁCMnMuCRmHvisamBaØkñúgtulakarkm <úCa Kingdom of Cambodia Nation Religion King Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia Royaume du Cambodge Chambres Extraordinaires au sein des Tribunaux Cambodgiens Nation Religion Roi Β₣ðĄеĕНеĄŪņй⅜ŵřеĠР₣ Trial Chamber Chambre de première instance TRANSCRIPT OF TRIAL PROCEEDINGS PUBLIC Case File Nº 002/19-09-2007-ECCC/TC 9 March 2015 Trial Day 254 Before the Judges: NIL Nonn, Presiding The Accused: NUON Chea YA Sokhan KHIEU Samphan Claudia FENZ Jean-Marc LAVERGNE YOU Ottara Lawyers for the Accused: Martin KAROPKIN (Reserve) Victor KOPPE THOU Mony (Reserve) SON Arun SUON Visal KONG Sam Onn Trial Chamber Greffiers/Legal Officers: Arthur VERCKEN SE Kolvuthy Matthew MCCARTHY Lawyers for the Civil Parties: For the Office of the Co-Prosecutors: Marie GUIRAUD Nicolas KOUMJIAN LOR Chunthy SONG Chorvoin VEN Pov Dale LYSAK For Court Management Section: UCH Arun SOUR Sotheavy 01074907 E1/273.1 Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia Trial Chamber – Trial Day 254 Case No. 002/19-09-2007-ECCC/TC 09/03/2015 I N D E X MR. NEANG OUCH ALIAS TA SAN (2-TCW-803) Questioning by the President .......................................................................................................... page 6 Questioning by Ms. Song Chorvoin .............................................................................................. page 10 Questioning by Mr. Koumjian ........................................................................................................ page 23 Page i 01074908 E1/273.1 Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia Trial Chamber – Trial Day 254 Case No. 002/19-09-2007-ECCC/TC 09/03/2015 List of Speakers: Language used unless specified otherwise in the transcript Speaker Language JUDGE FENZ English MR. KONG SAM ONN Khmer MR. -

Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University Southeast Asian Studies, Vol

https://englishkyoto-seas.org/ Shimojo Hisashi Local Politics in the Migration between Vietnam and Cambodia: Mobility in a Multiethnic Society in the Mekong Delta since 1975 Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 10, No. 1, April 2021, pp. 89-118. How to Cite: Shimojo, Hisashi. Local Politics in the Migration between Vietnam and Cambodia: Mobility in a Multiethnic Society in the Mekong Delta since 1975. Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 10, No. 1, April 2021, pp. 89-118. Link to this article: https://englishkyoto-seas.org/2021/04/vol-10-no-1-shimojo-hisashi/ View the table of contents for this issue: https://englishkyoto-seas.org/2021/04/vol-10-no-1-of-southeast-asian-studies/ Subscriptions: https://englishkyoto-seas.org/mailing-list/ For permissions, please send an e-mail to: english-editorial[at]cseas.kyoto-u.ac.jp Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 49, No. 2, September 2011 Local Politics in the Migration between Vietnam and Cambodia: Mobility in a Multiethnic Society in the Mekong Delta since 1975 Shimojo Hisashi* This paper examines the history of cross-border migration by (primarily) Khmer residents of Vietnam’s Mekong Delta since 1975. Using a multiethnic village as an example case, it follows the changes in migratory patterns and control of cross- border migration by the Vietnamese state, from the collectivization era to the early Đổi Mới reforms and into the post-Cold War era. In so doing, it demonstrates that while negotiations between border crossers and the state around the social accep- tance (“licit-ness”) and illegality of cross-border migration were invisible during the 1980s and 1990s, they have come to the fore since the 2000s. -

First Prospectus Supplement Dated 29 September 2017 to the Base Prospectus Dated 18 May 2017

FIRST PROSPECTUS SUPPLEMENT DATED 29 SEPTEMBER 2017 TO THE BASE PROSPECTUS DATED 18 MAY 2017 Peugeot S.A. (A société anonyme established under the laws of the Republic of France) €5,000,000,000 Euro Medium Term Note Programme guaranteed by GIE PSA Trésorerie This supplement (the First Prospectus Supplement) is supplemental to, and should be read in conjunction with, the Base Prospectus dated 18 May 2017 (the Base Prospectus), prepared in relation to the €5,000,000,000 Euro Medium Term Note Programme of Peugeot S.A. (PSA or the Issuer) guaranteed by GIE PSA Trésorerie (the Programme). The Base Prospectus constitutes a base prospectus for the purpose of the Directive 2003/71/EC as amended (the Prospectus Directive). The Autorité des marchés financiers (the AMF) has granted visa no. 17-210 on 18 May 2017 on the Base Prospectus. Application has been made for approval of this First Prospectus Supplement to the AMF in its capacity as competent authority pursuant to Article 212-2 of its Règlement Général which implements the Prospectus Directive. This First Prospectus Supplement constitutes a supplement to the Base Prospectus for the purposes of Article 16 of the Prospectus Directive and has been prepared for the purposes of (i) incorporating by reference the Issuer’s unaudited consolidated financial statements for the half year ended 30 June 2017 (ii) reflecting the upgraded rating attributed to the Issuer and the Guarantor by Moody’s Investors Services (Moody’s) and (iii) incorporating certain recent events in connection with the Issuer. As a result, certain modifications to the cover page of the Base Prospectus and to the sections “Summary”, “Résumé en Français (Summary in French)”, “Risk Factors”, “Documents Incorporated by Reference”, “Description of the Issuer”, “Recent Developments” and “General Information” of the Base Prospectus have been made. -

Cambodia PRASAC Microfinance Institution

Maybank Money Express (MME) Agent - Cambodia PRASAC Microfinance Institution Branch Location Last Update: 02/02/2015 NO NAME OF AGENT REGION / PROVINCE ADDRESS CONTACT NUMBER OPERATING HOUR 1 PSC Head Office PHNOM PENH #25, Str 294&57, Boeung Kengkang1,Chamkarmon, Phnom Penh, Cambodia 023 220 102/213 642 7.30am-4pm National Road No.5, Group No.5, Phum Ou Ambel, Krong Serey Sophorn, Banteay 2 PSC BANTEAY MEANCHEY BANTEAY MEANCHEY Meanchey Province 054 6966 668 7.30am-4pm 3 PSC POAY PET BANTEAY MEANCHEY Phum Kilometre lek 4, Sangkat Poipet, Krong Poipet, Banteay Meanchey 054 63 00 089 7.30am-4pm Chop, Chop Vari, Preah Net 4 PSC PREAH NETR PREAH BANTEAY MEANCHEY Preah, Banteay Meanchey 054 65 35 168 7.30am-4pm Kumru, Kumru, Thmor Puok, 5 PSC THMAR POURK BANTEAY MEANCHEY Banteay Meanchey 054 63 00 090 7.30am-4pm No.155, National Road No.5, Phum Ou Khcheay, Sangkat Praek Preah Sdach, Krong 6 PSC BATTAMBANG BATTAMBANG Battambang, Battambang Province 053 6985 985 7.30am-4pm Kansai Banteay village, Maung commune, Moung Russei district, Battambang 7 PSC MOUNG RUESSEI BATTAMBANG province 053 6669 669 7.30am-4pm 8 PSC BAVEL BATTAMBANG Spean Kandoal, Bavel, Bavel, BB 053 6364 087 7.30am-4pm Phnom Touch, Pech Chenda, 9 PSC PHNOM PROEK BATTAMBANG Phnum Proek, BB 053 666 88 44 7.30am-4pm Boeng Chaeng, Snoeng, Banan, 10 PSC BANANN BATTAMBANG Battambang 053 666 88 33 7.30am-4pm No.167, National Road No.7 Chas, Group No.10 , Phum Prampi, Sangkat Kampong 11 PSC KAMPONG CHAM KAMPONG CHAM Cham, Krong Kampong Cham, Kampong Cham Province 042 6333 000 7.30am-4pm -

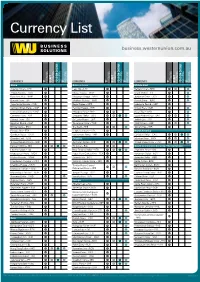

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

Climate-Friendly Agribusiness Value Chains Sector Project Rehabilitation of Prey Kdouch and Kraing Empil Irrigations Subprojects in Takeo Province

Initial Environmental Examination Project number: 48409-002 May 2021 Cambodia: Climate-Friendly Agribusiness Value Chains Sector Project Rehabilitation of Prey Kdouch and Kraing Empil irrigations subprojects in Takeo province Prepared by the loan consulting firms for the Ministry of Water Resources and Meteorology and the Asian Development Bank. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section on ADB’s website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (As of May 2021) Currency Unit = Riel/s (KR) KR1.00 = 0.00025 $ 1.00 = KR 4,052 ABBREVIATIONS AC - Agricultural Cooperative ADB - Asian Development Bank CFAVCP - Climate-Friendly Agribusiness Value Chains Sector Project EA - executive agency EIA - environmental impacts assessment EMP - environmental management plan ESO - environmental safeguards officer RGC - Royal Government of Cambodia JICA - Japan International Cooperation Agency IA - implementation agency IEE - initial environment examination IEIA - initial environmental impact assessment IPM - integrated pest management IWR - irrigation -

Treasury Reporting Rates of Exchange. As of March 31, 1979

^ J ;; u LIBRARY :' -'"- • 5-J 5 4 TREASURY REPORTING RATES OF EXCHANGE. AS OF MARCH 31, 1979 (/.S. DEPARIMENX-OF^JHE. TREASURY Fiscal Service Bureau of Government Financial Operations FOREWORD This report is prepared to promulgate exchange rate information pursuant to Section 613 of P.L. 87-195 dated September 4, 1961 (22 USC 2363(b)) which grants the Secretary of the Treasury "sole authority to establish for all foreign currencies or credits the exchange rates at which such currencies are to be reported by all agencies of the Government." The primary purpose of- this report is to insure that foreign currency reports prepared by agencies shall be consistent with regularly published Treasury foreign currency reports as to amounts stated in foreign currency units and U.S. dollar equivalents. This includes all foreign currencies in which the U.S. Government has an interest, including receipts and disbursements, accrued revenues and expenditures, authorizations, obligations, receivables and payables, refunds, and similar reverse transaction items. Exceptions to using the reporting rates as shown in this report are collections and refunds to be valued at specified rates set by international agreements, conversions of one foreign currency into another, foreign currencies sold for dollars and other types of transactions affecting dollar appropriations. See Chapter I Treasury Fiscal Requirements Manual 2-3200 for further details. This quarterly report reflects exchange rates at which foreign currencies can be acquired by the U.S. Government for official expenditures as reported by Disbursing Officers for each post on the last business day of the month prior to the date of the published report. -

CAMBODIA Griculture T T Extiles Ourism

CAPITAL: PHNOM PENH Pehn CAMBODIA LANGUAGES POPULATION OF KHMER 16.9 MILLION 181,035 SQ KM IN LAND AREA 47% OF POPULATION FAVOURITE SPORTS: ARE UNDER SOCCER 24 YEARS OLD MARTIAL ARTS SEPAK TAKRAW 97.9% (SIMILAR TO VOLLEYBALL) CAMBODIAN RIEL BUDDHIST MAJOR INDUSTRIES: RELIGION AGRICULTURE 1.1% ISLAM TOURISM EXTILES T 1% OTHER CAMBODIA A students spends time in the recently completed physiotherapy room at LaValla Students at LaValla school help to prepare food for a meal. The Cambodian proverb “Fear not the future, weep not for the past” captures the general approach to life in the country. Given the tragedies experienced during the Khmer Rouge regime, many have demonstrated immense forgiveness to live harmoniously with those who were a part of the regime as well as those Khmer who may Geography have lost loved ones. Cambodians also tend to have a stoic and cheerful demeanour. They rarely complain or The Kingdom of Cambodia is a Southeast Asian nation show discomfort. People often smile or laugh in various that borders Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam. Cambodia scenarios, regardless of whether the situation is positive has a tropical climate and experiences a monsoon or negative. season (May to November) and a dry season (December to April). The terrain is mostly low, flat plains, with AMS Projects in Cambodia – LaValla mountains in the southwest and north. The Lavalla Project, a work of Marist Solidarity Cambodia, History provides formal and inclusive education for children and young people with disabilities. As well the students have For 2,000 years Cambodia’s civilization was influenced by access to a comprehensive health and rehabilitation India and China - it also contributed significantly to these programme. -

Press Kit 2018

PRESS KIT 2018 - 33RD EDITION - • CONCEPT CARS AND AUTOMOTIVE DESIGN EXHIBITION • THE GRAND PRIZE OF THE FESTIVAL • THE MOST BEAUTIFUL CAR OF THE YEAR Paris - Hôtel national des Invalides www.festivalautomobile.com Contents Editorial by Rémi DEPOIX p. 1 Highlights of the 33rd Festival Automobile International p. 3 The Concept Cars and Automotive Design Exhibition p. 4 Some of the concept cars on show p 4 Design school corner p. 23 Focus on « The design : a french story » p. 24 Pratical informations p. 27 Exhibition’s campaign p. 28 The Jury 2018 p. 30 The Grand Prizes p. 31 The Most Beautiful Car of The Year 2017 p. 36 Winners of the Grand Prizes 2017 p. 38 CONTACTS p. 53 Editorial THE CONCEPT CAR Creating innovation and emotion We risk repeating it at the start of each new edition, but it cannot be denied: year after year, the International Automobile Festival claims its place as an event which is eagerly awaited by professionals and enthusiasts alike, and much to our delight … It is true that the show enables everyone to take stock of the changes taking place in design and the car itself, in the light of the new experiences these changes create and the new lifestyles they accompany. As the Festival marks its tenth anniversary in the Hôtel des Invalides, we are delighted to celebrate this presti- gious relationship. We are greatly indebted to General Bruno Le Ray, Military Governor of Paris, for continuing the work of his illustrious predecessors, who understood the importance of opening up the Invalides to the cultural and economic life of our times.