Cambodia: from Dependency to Sovereignty – Emerging National Leadership

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Shadows: Women, Power and Politics in Cambodia

In the Shadows: Women, Power and Politics in Cambodia Kate Frieson CAPI Associate and United N ations Regional Spokesperson, UNMIBH (UN mission in Bosnia Hercegovina) Occasional Paper No. 26 June 2001 Copyright © 2001 Centre for Asia-Pacific Initiatives Box 1700, STN CSC Victoria, BC Canada V8W 2Y2 Tel. : (250) 721-7020 Fax : (250) 721-3107 E-mail: [email protected] National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Frieson, Kate G. (Kate Grace), 1958- In the Shadows: Women, Power and Politics in Cambodia (CAPI occasional paper series ; 26) ISBN 1-55058-230-5 1. Cambodia–Social conditions. 2. Cambodia–Politics and government. 3. Women in politics–Cambodia. I. UVic Centre for Asia-Pacific Initiatives. II. Title. III. Series: Occasional papers (UVic Centre for Asia-Pacific Initiatives) ; #26. DS554.8.F74 2001 305.42'09596 C2001-910945-8 Printed in Canada Table of Contents Theoretical Approaches to Gender and Politics ......................................1 Women and the Politics of Socialization ............................................2 Women and the State: Regeneration and the Reproduction of the Nation ..................4 Women and the Defense of the State during War-Time ................................8 Women as Defenders of the Nation ...............................................12 Women in Post-UNTAC Cambodia ..............................................14 Conclusion ..................................................................16 Notes ......................................................................16 In the Shadows: Women, Power and Politics in Cambodia Kate Frieson, University of Victoria "Behind almost all politicians there are women in the shadows" Anonymous writer, Modern Khmer News, 1954 Although largely unscribed in historical writings, women have played important roles in the Cambodian body politic as lance-carrying warriors and defenders of the Angkorean kingdom, influential consorts of kings, deviant divas, revolutionary heroines, spiritual protectors of Buddhist temples, and agents of peace. -

What Drives Urbanisation in Modern Cambodia? Some Counter-Intuitive Findings

sustainability Article What Drives Urbanisation in Modern Cambodia? Some Counter-Intuitive Findings Partha Gangopadhyay * , Siddharth Jain and Agung Suwandaru School of Business, Western Sydney University, Penrith NSW 2751, Australia; [email protected] (S.J.); [email protected] (A.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 23 October 2020; Accepted: 2 December 2020; Published: 8 December 2020 Abstract: The history of urbanisation in Cambodia is a fascinating case study. During 1965–1973, the Vietnam war triggered the mass migration of Cambodians to the urban centres as its rural economy was virtually annihilated by an unprecedented cascade of aerial bombardments. During the Pol Pot regime, 1975–1979, urban areas were hastily closed down by the Khmer Rouge militia that led to the phase of forced de-urbanisation. With the ouster of the Pol Pot regime, since 1993 a new wave of urbanisation has taken shape for Cambodia. Rising urban population in a few urban regions has triggered multidimensional problems in terms of housing, employment, infrastructure, crime rates and congestions. This paper investigates the significant drivers of urbanisation since 1994 in Cambodia. Despite severe limitations of the availability of relevant data, we have extrapolated the major long-term drivers of urbanization by using autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) analysis and nonlinear autoregressive distributed lag (NARDL) models. Our main finding is that FDI flows have a significant short-run and long-run asymmetric effect on urbanisation. We conclude that an increase in FDI boosts the pull-factor behind rural–urban migration. At the same time, a decrease in FDI impoverishes the economy and promotes the push-factor behind the rural–urban migration. -

Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University Southeast Asian Studies, Vol

https://englishkyoto-seas.org/ Shimojo Hisashi Local Politics in the Migration between Vietnam and Cambodia: Mobility in a Multiethnic Society in the Mekong Delta since 1975 Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 10, No. 1, April 2021, pp. 89-118. How to Cite: Shimojo, Hisashi. Local Politics in the Migration between Vietnam and Cambodia: Mobility in a Multiethnic Society in the Mekong Delta since 1975. Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 10, No. 1, April 2021, pp. 89-118. Link to this article: https://englishkyoto-seas.org/2021/04/vol-10-no-1-shimojo-hisashi/ View the table of contents for this issue: https://englishkyoto-seas.org/2021/04/vol-10-no-1-of-southeast-asian-studies/ Subscriptions: https://englishkyoto-seas.org/mailing-list/ For permissions, please send an e-mail to: english-editorial[at]cseas.kyoto-u.ac.jp Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 49, No. 2, September 2011 Local Politics in the Migration between Vietnam and Cambodia: Mobility in a Multiethnic Society in the Mekong Delta since 1975 Shimojo Hisashi* This paper examines the history of cross-border migration by (primarily) Khmer residents of Vietnam’s Mekong Delta since 1975. Using a multiethnic village as an example case, it follows the changes in migratory patterns and control of cross- border migration by the Vietnamese state, from the collectivization era to the early Đổi Mới reforms and into the post-Cold War era. In so doing, it demonstrates that while negotiations between border crossers and the state around the social accep- tance (“licit-ness”) and illegality of cross-border migration were invisible during the 1980s and 1990s, they have come to the fore since the 2000s. -

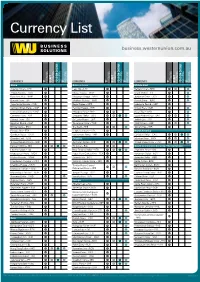

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

Treasury Reporting Rates of Exchange. As of March 31, 1979

^ J ;; u LIBRARY :' -'"- • 5-J 5 4 TREASURY REPORTING RATES OF EXCHANGE. AS OF MARCH 31, 1979 (/.S. DEPARIMENX-OF^JHE. TREASURY Fiscal Service Bureau of Government Financial Operations FOREWORD This report is prepared to promulgate exchange rate information pursuant to Section 613 of P.L. 87-195 dated September 4, 1961 (22 USC 2363(b)) which grants the Secretary of the Treasury "sole authority to establish for all foreign currencies or credits the exchange rates at which such currencies are to be reported by all agencies of the Government." The primary purpose of- this report is to insure that foreign currency reports prepared by agencies shall be consistent with regularly published Treasury foreign currency reports as to amounts stated in foreign currency units and U.S. dollar equivalents. This includes all foreign currencies in which the U.S. Government has an interest, including receipts and disbursements, accrued revenues and expenditures, authorizations, obligations, receivables and payables, refunds, and similar reverse transaction items. Exceptions to using the reporting rates as shown in this report are collections and refunds to be valued at specified rates set by international agreements, conversions of one foreign currency into another, foreign currencies sold for dollars and other types of transactions affecting dollar appropriations. See Chapter I Treasury Fiscal Requirements Manual 2-3200 for further details. This quarterly report reflects exchange rates at which foreign currencies can be acquired by the U.S. Government for official expenditures as reported by Disbursing Officers for each post on the last business day of the month prior to the date of the published report. -

Cambodia: Background and U.S

Order Code RL32986 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Cambodia: Background and U.S. Relations July 8, 2005 Thomas Lum Asian Affairs Specialist Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Cambodia: Background and U.S. Relations Summary Cambodia has made some notable progress, with foreign assistance, in developing its economy, nurturing a civil society, and holding elections that are at least procedurally democratic. A number of significant problems remain, however. Weak legal and financial institutions, corruption, political violence, and the authoritarian tendencies of the Cambodian Prime Minister, Hun Sen, have discouraged foreign investment and strained U.S.-Cambodian relations. U.S. interests in Cambodia include human rights, foreign assistance, trade, and counter terrorism. Several current measures by the United States government reflect human rights concerns in Cambodia. Since 1998, foreign operations appropriations legislation has barred assistance to the Central Government of Cambodia in response to Prime Minister Hun Sen’s seizure of power in 1997 and sporadic political violence against the opposition. The United States has also withheld assistance to the Khmer Rouge tribunal unless standards of judicial independence and fairness are met. Despite these restrictions, Cambodia remains the third largest recipient of United States assistance in Southeast Asia after Indonesia and the Philippines. S.Res. 65would call upon the Government of Cambodia to release Member of Parliament Cheam Channy from prison and to restore the immunity from prosecution of opposition parliamentarians. In 2005, the State Department placed Cambodia in Tier 3 as a country that had not made adequate efforts to eliminate trafficking in persons. -

Between Water and Land: Urban and Rural Settlement Forms in Cambodia with Special Reference to Phnom Penh

Between water and land: urban and rural settlement forms in Cambodia with special reference to Phnom Penh Thomas Kolnberger Identités. Politiques, Sociétés, Espaces (IPSE), Université du Luxembourg, Campus Belval, Maison des Sciences Humaines, 11, Porte des Sciences, L-4366 Esch/Alzette, Luxembourg. E-mail: [email protected] Revised version received 19 May 2015 Abstract. In explaining urban form in Cambodia, morphological continuity between rural and urban forms is examined. Environment and agrarian land use are decisive factors in the location and shape of plots in the countryside. Under conditions of higher population density, urban plots tend to be compressed versions of rural ones. Adopting a historico-geographical approach, the development of the form of Phnom Penh as a colonial city and capital of a French protectorate is explored as an example of the persistence of a rural settlement pattern in a specific urban context. Keywords: Cambodia, Phnom Penh, rural morphology, urban morphology, plot form The shapes of plots have become a significant, plain, made lowland living sustainable, albeit not widely studied, aspect of both urban allowed the population to expand and rendered and rural settlement morphology. However, empire building possible. This explains why much of the attention given to this topic the lowlands have been the demographic and hitherto has focused on Europe. This paper economic core area of polities since the Khmer examines urban and rural settlement form, realm of Angkor (ninth to fifteenth centuries) especially the relationship between rural and and its successor kingdoms up to the French urban plots, in a very different environment – colonial era (1863-1953) and the period of the core area of Cambodia – giving particular independence. -

CAMBODIA Griculture T T Extiles Ourism

CAPITAL: PHNOM PENH Pehn CAMBODIA LANGUAGES POPULATION OF KHMER 16.9 MILLION 181,035 SQ KM IN LAND AREA 47% OF POPULATION FAVOURITE SPORTS: ARE UNDER SOCCER 24 YEARS OLD MARTIAL ARTS SEPAK TAKRAW 97.9% (SIMILAR TO VOLLEYBALL) CAMBODIAN RIEL BUDDHIST MAJOR INDUSTRIES: RELIGION AGRICULTURE 1.1% ISLAM TOURISM EXTILES T 1% OTHER CAMBODIA A students spends time in the recently completed physiotherapy room at LaValla Students at LaValla school help to prepare food for a meal. The Cambodian proverb “Fear not the future, weep not for the past” captures the general approach to life in the country. Given the tragedies experienced during the Khmer Rouge regime, many have demonstrated immense forgiveness to live harmoniously with those who were a part of the regime as well as those Khmer who may Geography have lost loved ones. Cambodians also tend to have a stoic and cheerful demeanour. They rarely complain or The Kingdom of Cambodia is a Southeast Asian nation show discomfort. People often smile or laugh in various that borders Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam. Cambodia scenarios, regardless of whether the situation is positive has a tropical climate and experiences a monsoon or negative. season (May to November) and a dry season (December to April). The terrain is mostly low, flat plains, with AMS Projects in Cambodia – LaValla mountains in the southwest and north. The Lavalla Project, a work of Marist Solidarity Cambodia, History provides formal and inclusive education for children and young people with disabilities. As well the students have For 2,000 years Cambodia’s civilization was influenced by access to a comprehensive health and rehabilitation India and China - it also contributed significantly to these programme. -

Treasury Reporting Rates of Exchange As of March 31, 1978

TREASURY REPORTING RATES OF EXCHANGE AS OF MARCH 31, 1978 DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY Fiscal Service Bureau of Government Financial Operations FOREWORD This report is prepared to promulgate exchange rate information pursuant to Section 613 of P.L. 87-195 dated September 4, 1961 (22 USC 2363(b)) which grants the Secretary of the Treasury "sole authority to establish for all foreign currencies or credits the exchange rates at which such currencies are to be reported by all agencies of the Government." The primary purpose of this report is to insure that foreign currency reports prepared by agencies shall be consistent with regularly published Treasury foreign currency reports as to amounts stated in foreign currency units and U.S. dollar equivalents. This includes all foreign currencies in which the U.S. Government has an interest, including receipts and disbursements, accrued revenues and expenditures, authorizations, obligations, receivables and payables, refunds, and similar reverse transaction items. Exceptions to using the reporting rates as shown in this report are collections and refunds to be valued at specified rates set by international agreements, conversions of one foreign currency into another, foreign currencies sold for dollars and other types of transactions affecting dollar appropriations. See Treasury Circular No, 930, Section 4a (3) of Procedures Memorandum No. 1 for further details. This quarterly report reflects exchange rates at which foreign currencies can be acquired by the U.S. Government for official expenditures as reported by Disbursing Officers for each post on the last business day of the month prior to the date of the published report. -

Women in Cambodia – Analysing the Role and Influence of Women in Rural Cambodian Society with a Special Focus on Forming Religious Identity

WOMEN IN CAMBODIA – ANALYSING THE ROLE AND INFLUENCE OF WOMEN IN RURAL CAMBODIAN SOCIETY WITH A SPECIAL FOCUS ON FORMING RELIGIOUS IDENTITY by URSULA WEKEMANN submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF THEOLOGY in the subject MISSIOLOGY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: DR D C SOMMER CO-SUPERVISOR: PROF R W NEL FEBRUARY 2016 1 ABSTRACT This study analyses the role and influence of rural Khmer women on their families and society, focusing on their formation of religious identity. Based on literature research, the role and influence of Khmer women is examined from the perspectives of history, the belief systems that shape Cambodian culture and thinking, and Cambodian social structure. The findings show that although very few Cambodian women are in high leadership positions, they do have considerable influence, particularly within the household and extended family. Along the lines of their natural relationships they have many opportunities to influence the formation of religious identity, through sharing their lives and faith in words and deeds with the people around them. A model based on Bible storying is proposed as a suitable strategy to strengthen the natural influence of rural Khmer women on forming religious identity and use it intentionally for the spreading of the gospel in Cambodia. KEY WORDS Women, Cambodia, rural Khmer, gender, social structure, family, religious formation, folk-Buddhism, evangelization. 2 Student number: 4899-167-8 I declare that WOMEN IN CAMBODIA – ANALYSING THE ROLE AND INFLUENCE OF WOMEN IN RURAL CAMBODIAN SOCIETY WITH A SPECIAL FOCUS ON FORMING RELIGIOUS IDENTITY is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. -

Cambodia Economic Update

Public Disclosure Authorized REAL GDP GROWTH TOURIST ARRIVALS (Y/Y % Public Disclosure Authorized 12 30 RIGHT SCALE) 10 20 GARMENT EXPORTS (Y/Y % CHANGE, RIGHT SCALE) 8 10 6 0 4 -10 Public Disclosure Authorized 2 0 -20 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 THE WORLD BANK Public Disclosure Authorized SEPTEMBER 2013 RESILIENCE AMIDST A CHALLENGING ENVIRONMENT CAMBODIA ECONOMIC UPDATE SEPTEMBER 2013 @ All rights reserved This Cambodia Economic Update is a product of the World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in the Update are those of World Bank staff, and do not necessarily reflect the views of its management, Executive Board, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Cambodia Economic Update is a product of the staff of the World Bank. It was prepared by Sodeth Ly, and reviewed and edited by Enrique Aldaz-Carroll, Poverty Reduction and Economic Management (PREM) Sector Department, Cambodia Country Office, the World Bank. The Poverty Team, led by Samsen Neak, contributed the poverty section for the Update. The team worked under the guidance of Mathew A. Verghis, Lead Economist and Sector Manager, PREM Sector Department, and Alassane Sow, Country Manager for Cambodia. The Update is produced bi-annually to provide up-to-date information on macroeconomic developments in Cambodia. The Update is published and distributed widely to the Cambodian authorities, the development partner community, the private sector, think tanks, civil society organizations, non-government organizations, and academia. -

Prince Sihanouk: the Model of Absolute Monarchy in Cambodia 1953-1970

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2013 Prince Sihanouk: The Model of Absolute Monarchy in Cambodia 1953-1970 Weena Yong Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, Asian Art and Architecture Commons, Asian History Commons, Environmental Design Commons, Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons, Military, War, and Peace Commons, National Security Law Commons, South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons, and the Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons Recommended Citation Yong, Weena, "Prince Sihanouk: The Model of Absolute Monarchy in Cambodia 1953-1970". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2013. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/309 Prince Norodom Sihanouk Prince Norodom The Model of Absolute Monarchy in Cambodia 1953-1970 by Prince Sihanouk: The Model of Absolute Monarchy in Cambodia By Weena Yong Advised by Michael Lestz Janet Bauer Zayde Gordon Antrim A Thesis Submitted to the International Studies Program of Trinity College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Bachelor of Arts Degree © May 2013 1 For my parents, MiOk Mun and Yong Inn Hoe, My brothers, KeeSing Benjamin and KeeHup Arie, My sister, Lenna XingMei And to all my advisors and friends, Whom have inspired and supported me Every day. 2 Abstract This thesis addresses Prince Sihanouk and the model of absolute monarchy in Cambodia during his ‘golden era.’ What is the legacy bequeathed to his country that emanated from his years as his country’s autocratic leader (1954-1970)? What did he leave behind? My original hypothesis was that Sihanouk was a libertine and ruthless god-king who had immense pride for his country.