1 ELEMENT STEWARDSHIP ABSTRACT for Rhamnus Cathartica, Rhamnus Frangula (Syn. Frangula Alnus) Buckthorns to the User: Element St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Invasion of Transition Hardwood Forests by Exotic Rhamnus Frangula: Chronology and Site Requirements

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Spring 2007 Invasion of transition hardwood forests by exotic Rhamnus frangula: Chronology and site requirements Hanna S. Wingard University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Wingard, Hanna S., "Invasion of transition hardwood forests by exotic Rhamnus frangula: Chronology and site requirements" (2007). Master's Theses and Capstones. 286. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/286 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INVASION OF TRANSITION HARDWOOD FORESTS BY EXOTIC RHAMNUS FRANGULA: CHRONOLOGY AND SITE REQUIREMENTS BY HANNA S. WINGARD Baccalaureate Degree, University of Michigan, 2000 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of M aster of Science in Natural Resources May, 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1443642 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

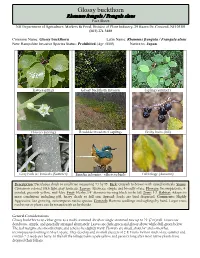

Glossy Buckthorn Rhamnusoriental Frangula Bittersweet / Frangula Alnus Control Guidelines Fact Sheet

Glossy buckthorn Oriental bittersweet Rhamnus frangula / Frangula alnus Control Guidelines Fact Sheet NH Department of Agriculture, Markets & Food, Division of Plant Industry, 29 Hazen Dr, Concord, NH 03301 (603) 271-3488 Common Name: Glossy buckthorn Latin Name: Rhamnus frangula / Frangula alnus New Hampshire Invasive Species Status: Prohibited (Agr 3800) Native to: Japan leaves (spring) Glossy buckthorn invasion Sapling (summer) Flowers (spring) Roadside invasion of saplings Fleshy fruits (fall) Gray bark w/ lenticels (Summer) Emodin in berries - effects to birds Fall foliage (Autumn) Description: Deciduous shrub or small tree measuring 20' by 15'. Bark: Grayish to brown with raised lenticels. Stems: Cinnamon colored with light gray lenticels. Leaves: Alternate, simple and broadly ovate. Flowers: Inconspicuous, 4- petaled, greenish-yellow, mid-May. Fruit: Fleshy, 1/4” diameter turning black in the fall. Zone: 3-7. Habitat: Adapts to most conditions including pH, heavy shade to full sun. Spread: Seeds are bird dispersed. Comments: Highly Aggressive, fast growing, outcompetes native species. Controls: Remove seedlings and saplings by hand. Larger trees can be cut or plants can be treated with an herbicide. General Considerations Glossy buckthorn can either grow as a multi-stemmed shrub or single-stemmed tree up to 23’ (7 m) tall. Leaves are deciduous, simple, and generally arranged alternately. Leaves are dark-green and glossy above while dull-green below. The leaf margins are smooth/entire and tend to be slightly wavy. Flowers are small, about ¼” and somewhat inconspicuous forming in May to June. They develop and in small clusters of 2-8. Fruits form in mid to late summer and contain 2-3 seeds per berry. -

Botanical Name Common Name

Approved Approved & as a eligible to Not eligible to Approved as Frontage fulfill other fulfill other Type of plant a Street Tree Tree standards standards Heritage Tree Tree Heritage Species Botanical Name Common name Native Abelia x grandiflora Glossy Abelia Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes White Forsytha; Korean Abeliophyllum distichum Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes Abelialeaf Acanthropanax Fiveleaf Aralia Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes sieboldianus Acer ginnala Amur Maple Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes Aesculus parviflora Bottlebrush Buckeye Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes Aesculus pavia Red Buckeye Shrub, Deciduous No No Yes Yes Alnus incana ssp. rugosa Speckled Alder Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Alnus serrulata Hazel Alder Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Amelanchier humilis Low Serviceberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Amelanchier stolonifera Running Serviceberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes False Indigo Bush; Amorpha fruticosa Desert False Indigo; Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No No Not eligible Bastard Indigo Aronia arbutifolia Red Chokeberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Aronia melanocarpa Black Chokeberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Aronia prunifolia Purple Chokeberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Groundsel-Bush; Eastern Baccharis halimifolia Shrub, Deciduous No No Yes Yes Baccharis Summer Cypress; Bassia scoparia Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes Burning-Bush Berberis canadensis American Barberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Common Barberry; Berberis vulgaris Shrub, Deciduous No No No No Not eligible European Barberry Betula pumila -

Natural Resources

Plants That Cause Problems – “Invasive Species” DestinationOakland.com STOP! What is an Invasive Species? Imagine spring wildflowers covered with a mat of twisted green vines. This is a sign that Oakland County Offenders invasive plants have moved in and native species have moved out. Invasive plant species originate in other parts of the world and are introduced into to the United States through flower a variety of ways. Not all plants introduced from other countries become invasive. The term invasive species is reserved for plants that grow and reproduce rapidly, causing changes to the areas where they become established. Invasive species impact our health, our economy seed and the environment, and can cost the United States $120 billion annually! flower pod flower A Ticking Time Bomb Growing unnoticed at first, invasive species spread and cover the landscape. They change the seed pod fruit ecology, affecting wildlife communities and the soil. Over time, invasive plant species form a monoculture in which the only plant growing is the invasive plant. Plants with Super Powers Invasive species have super powers to alter the ecological balance of nature. They flourish seed because controls in their native lands do not exist here. The Nature Conservancy ranks invasive species as the second leading cause of species extinction worldwide. Negative Effects of Invasive Species • Changes in hydrology— seed dispersal wetlands dry out • Release of chemicals into the soil that inhibit Black Swallow-wort Cynanchum louiseae & the growth of other plants. This is known as Pale Swallow-wort Cynanchum rossicum Autumn Olive Elaeagnus umbellate Garlic Mustard Allaria periolata Allelopathy. -

Glossy Buckthorn Frangula Alnus

Invasive Species—Best Control Practices Michigan Department of Natural Resources Michigan Natural Features Inventory 2/2012 Glossy buckthorn Frangula alnus Glossy buckthorn is native to Eurasia but has been com- monly planted in this country as a hedge and for wildlife food and cover. It was widely recommended for conserva- tion plantings in the Midwest until its invasive tendencies became apparent; it creates dense thickets and out-com- petes native vegetation. Its fruit is widely dispersed by birds and small mammals. Glossy buckthorn, like many invasive shrubs, leafs out early in the spring and retains its leaves late into fall, increasing its energy production and shading out native plants. It is a particular pest on wet sites and poses a significant threat to Michigan’s rich prairie fens, as well as other wetland com- munities. It is also successful on many upland sites including old fields, roadsides and open woods. Glossy buckthorn is an alternate host for alfalfa mosaic virus and crown fungus, which causes oat rust disease. It has also been implicated as a possible host for the soybean aphid. It is widely distributed in some parts of the state, but is just beginning to appear in others. If it is caught early in its initial invasion, it may be eradicated completely. Robert Vidéki, Doronicum Kft., Bugwood.org Identification Flowers: Habit: Glossy buckthorn flowers Glossy buckthorn is a small tree or shrub with a spreading are tiny with five greenish- crown growing up to 6 m (20 ft) tall. Typically, it has multiple white petals, arranged in stems when young, and develops into a tree with a trunk clusters at the bases of the that may reach 25 cm (10 in) in diameter at maturity. -

Fecundity Limits in Frangula Alnus (Rhamnaceae) Relict Populations at the Species’ Southern Range Margin

POPULATION ECOLOGY Arndt Hampe Fecundity limits in Frangula alnus (Rhamnaceae) relict populations at the species’ southern range margin Abstract The geographic range of many temperate plant through past decades leading to an earlier onset of species is constrained by climate, but it remains little summer drought. This trend and its adverse effects on known how climate affects population performance at seed production may contribute to explaining the recent low-latitude range margins. This study investigated the decline of F. alnus at its southwestern range limit. reproduction of the Eurasian tree Frangula alnus in relict populations near its southwestern range limit in south- Keywords Global change Æ Hydric stress Æ ern Spain. The aim was to identify the principal stages Mediterranean climate Æ Phenology Æ Pollen limitation and causes of ovule loss experienced by these marginal populations. More than 6,800 flowers were monitored over 2 years, insect observations and different experi- ments were carried out to assess levels of pollen and Introduction resource limitation, as well as the influence of flowering phenology on seed production. Most ovule losses oc- The geographic range of many temperate plant species is curred during flower anthesis and were due to strong determined by climate (Woodward 1987). Presumably, cross-pollen limitation. Fruit set was affected by tree populations from the centre of the range experience the size, light regime and flowering phenology, probably most favourable environmental conditions, while envi- through their effects on pollinator behaviour. Fruit set ronmental suitability decreases with distance from the was almost zero throughout the first half of the flower- distribution centre and populations become smaller and ing season. -

Frangula Alnus P

NEW YORK NON-NATIVE PLANT INVASIVENESS RANKING FORM Scientific name: Frangula alnus P. Mill. (Rhamnus frangula) USDA Plants Code: FRAL4 Common names: Glossy buckthorn Native distribution: Eurasia Date assessed: November 6, 2008; edited 3/27/2009 & May 21, 2009 Assessors: Steve Glenn, Gerry Moore Reviewers: LIISMA SRC Date Approved: November 19, 2008 Form version date: 22 October 2008 New York Invasiveness Rank: High (Relative Maximum Score 70.00-80.00) Distribution and Invasiveness Rank (Obtain from PRISM invasiveness ranking form) PRISM Status of this species in each PRISM: Current Distribution Invasiveness Rank 1 Adirondack Park Invasive Program Not Assessed Not Assessed 2 Capital/Mohawk Not Assessed Not Assessed 3 Catskill Regional Invasive Species Partnership Not Assessed Not Assessed 4 Finger Lakes Not Assessed Not Assessed 5 Long Island Invasive Species Management Area Widespread High 6 Lower Hudson Not Assessed Not Assessed 7 Saint Lawrence/Eastern Lake Ontario Not Assessed Not Assessed 8 Western New York Not Assessed Not Assessed Invasiveness Ranking Summary Total (Total Answered*) Total (see details under appropriate sub-section) Possible 1 Ecological impact 40 (30) 17 2 Biological characteristic and dispersal ability 25 (23) 18 3 Ecological amplitude and distribution 25 (25) 21 4 Difficulty of control 10 (10) 8 Outcome score 100 (84)b 62a † Relative maximum score 72.73 § New York Invasiveness Rank High (Relative Maximum Score 70.00-80.00) * For questions answered “unknown” do not include point value in “Total Answered Points Possible.” If “Total Answered Points Possible” is less than 70.00 points, then the overall invasive rank should be listed as “Unknown.” †Calculated as 100(a/b) to two decimal places. -

List of Paludicultural Plants and Utilisation Options (Selection)

Paludicultural plants and utilisation options (selection) English name Latin name Most promising uses Other uses Peat moss Sphagnum spp. Founder material for restoration and Sphagnum farming Insulation and packaging material Orchid cultivation Food preservation Horticultural growing media replacing peat Medical dressings, diapers, and substrates for carnivorous plants, for vivaria with sanitary towels amphibians, reptiles and spiders, Sphagnum extracts as source of substrate for hanging baskets, wreathes and vegetation walls natural sunscreen Sundew Drosera rotundifolia Medicinal uses Vegetarian rennet for cheese making Cattail, Bulrush Typha angustifolia, Insulation material Combustion Typha latifolia Filling material (seed hairs) Biogas Construction material Extraction of proteins likely Packaging and disposable tableware Horticultural growing media replacing peat very Fodder Pollen for feeding predatory mites (pest control in glasshouses) Reed Phragmites australis Thatching material Paper Insulation material Biogas Construction material Liquid fuels cultivation Packaging and disposable tableware Extraction of proteins of Fodder Silicon from reed leaves for high‐ Combustion performance energy storage devices Giant cane Arundo donax Combustion Biogas Uptake Reed Manna Grass Glyceria maxima Fodder Biogas Extraction of proteins Reed canary grass Phalaris arundinacea Packaging and disposable tableware Paper Panels Biogas Fodder Liquid fuels Bedding Extraction of proteins Combustion Sedges Carex -

Alana Cole Conservation Area Management Plan

ALANA COLE PARK LAND MANAGEMENT PLAN Prepared for: City of Lebanon, New Hampshire Planning Department ________________________________________________________________________ Moosewood Ecological LLC Innovative Conservation Solutions for New England PO Box 9—Chesterfield, NH 03443 [email protected] (603) 363-8489 ALANA COLE PARK LAND MANAGEMENT PLAN Prepared for: City of Lebanon, New Hampshire Planning Department JEFFRY N. LITTLETON Conservation Ecologist PO Box 9 Chesterfield, NH 03443 (603) 363-8489 [email protected] www.moosewoodecological.com December 2009 Cover photograph – Sign at trailhead next to parking area. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................1 CURRENT CONDITIONS and RECOMMENDATIONS ......................................5 CONCLUSIONS .......................................................................................................24 RESOURCE DOCUMENTS ...................................................................................25 APPENDICES A – Invasive Plant Management Options ..........................................................26 ________________________________________________________________________ Alana Cole Park ii Lebanon, NH ________________________________________________________________________ Alana Cole Park iii Lebanon, NH INTRODUCTION Background The City of Lebanon received a grant from the Upper Connecticut River Mitigation and Enhancement Fund in 2009 to develop a land -

Palustrine Communities Descriptions

Classification of the Natural Communities of Massachusetts Palustrine Communities Descriptions Palustrine Communities Descriptions These are wetland natural communities in which the species composition is affected by flooding or saturated soil conditions, and the water table is at or near the surface most of the year. Note: The term “wetland” is not used in the sense of a “jurisdictional wetland,” which has a legal definition. Pitcher Plant, photo by Patricia Swain, NHESP Classification of the Natural Communities of Massachusetts Palustrine Communities Descriptions Acidic Graminoid Fen Community Code: CP2B0B1000 State Rank: S3 Concept: Mixed graminoid/herbaceous acidic peatlands with some groundwater and/or surface water flow but no calcareous seepage. Shrubs occur in clumps but are not dominant throughout. Environmental Setting: Peatlands, commonly called bogs or fens, are wetland communities on peat, which is an accumulation of incompletely decomposed organic material. Bogs and acidic fens are northern communities; Massachusetts is at the southern limit of the geographic range of acidic peatlands, meaning that climatic conditions are marginal and occurrences are patchy. Acidic Graminoid Fens are sedge- and sphagnum-dominated peatlands that are weakly minerotrophic (mineral-rich). Acidic Graminoid Fens typically have some surface water inflow and some groundwater connectivity. Inlets and outlets are usually present, and standing water is present throughout much of the growing season. Peat mats are quaking and often unstable. Vegetation Description: Species of sphagnum moss (Sphagnum spp.) are the most common plants in all acidic peatlands. As with vascular plants, the particular sphagnum species present vary depending on acidity and nutrient availability. Acidic Graminoid Fens have the most diversity of vascular plants of the acidic peatland communities. -

Invasive Plant Control Buckthorns – Rhamnus Cathartica & Frangula Alnus

Pest Management – Invasive Plant Control Buckthorns – Rhamnus cathartica & Frangula alnus Conservation Practice Job Sheet NH-595 Common Buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica L.) Glossy Buckthorn (Frangula alnus Mill.) Buckthorns upward toward the tip. Branch stems end in small The buckthorns are native to Eurasia. They were thorns that appear between the last pair of buds. probably introduced to the US before 1800 but did not Fragrant flowers with four greenish-yellow petals become widespread until the early 1900s. They are develop into black fruit (3-4 seeds) that may persist now found throughout much of the central and well into winter. northern United States and into Canada. Glossy buckthorn has thin, alternate glossy leaves Common and glossy buckthorns are shrubs or small which are oblong to elliptical with more than 5 pairs trees that readily invade natural areas, establishing of veins and with smooth or wavy margins. Buds are dense, even-aged thickets which crowd or shade out rust-colored and naked. Five parted, yellowish-green native plants. The buckthorns reproduce sexually by flowers ripen from red to black (2-3 seeds). seed and vegetatively through root suckering. Both buckthorns produce fruits that are readily eaten, and Similar Natives thus seeds are spread by wildlife. The native shrub Alderleaf Buckthorn (Rhamnus alnifolia L’Her) has alternate leaves with 8-9 pairs of Buckthorns generally leaf-out earlier and retain their veins and toothed margins. The leaf surface is leaves longer than many native shrubs. This trait, puckered (like seer sucker fabric). The buds are scaly shared by many invasive shrubs, gives them a (not naked) but lack thorn tips of common buckthorn. -

South Forty Solar Farm Vegetation Management Plan

South Forty Solar Farm Vegetation Management Plan TCE# 2013113-1 | South Forty Solar, LLC Burlington, Vermont Date: April 2, 2014 Prepared For: South Forty Solar, LLC c/o Frank von Turkovich One National Life Drive Montpelier, VT 05604 Prepared By: Karina E. Dailey, PWS April Mouleart, PWS Northwoods Ecological Consulting TABLE OF CONTENTS Project Purpose ............................................................................................................... 1 Site Description ................................................................................................................ 12 Vegetative Cover types and Natural Community Description ............................ 2 Prescribed Management .............................................................................................. 3 Treatment - Cutting and Mowing ............................................................................... 3 Non – Native Invasive Species Control Plan (NISCP) .............................................. 4 Summary ........................................................................................................................... 5 References ....................................................................................................................... 6 Appendix 1 – Vegetative Management Zone Map ............................................... 7 Appendix 2 – Buffer Zone Shade Line Diagram ....................................................... 8 Appendix 3 – Photographic Documentation ..........................................................