W [7Ns -MW» Ηοπηι Nannn -»Ow "Pypw . Onn > Civ Vino

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Temurah 018.Pub

ה' אב תשע“ט Tues, Aug 6 2019 י“ח תמורה OVERVIEW of the Daf Distinctive INSIGHT 1) Clarifying the Mishnah (cont.) The offspring of a shelamim must be left to die אלא אמר רב חייא בר אבא אמר ר ‘ יוחנן היינו טעמא דר ‘ אליעזר -The Gemara continues to analyze one of the exposi גזירה שמא יגדל מהם עדרים עדרים tions cited in the Baraisa that was cited to explain the rul- ings in the Mishnah. n the Mishnah on our daf we find a disagreement R’ Akiva’s exposition in the Baraisa is clarified. I among Tannaim regarding the offspring of a shelamim The exchange between the two Baraisos concerning their respective sources for the Mishnah’s rulings is pre- animal. R’ Eliezer says that the offspring of a shelamim sented. may not be brought as a shelamim. Rather, due to a rab- 2) MISHNAH: The Mishnah presents different opinions binic consideration which the Gemara explains, the ani- regarding the status of the offspring of shelamim. mal must be locked in a closed cell and left to die. 3) Offspring of Shelamim Chachamim hold that this offspring may be brought as a R’ Ami in the name of R’ Yochanan suggests a source shelamim. In the Gemara, R’ Chiya b. Abba concludes in for R’ Eliezer’s position that the offspring of a shelamim the name of R’ Yochanan that the reason for the opinion may not be offered as a shelamim. of R’ Eliezer is that we are concerned that if it were permit- This explanation is rejected in favor of another expla- ted to bring this animal as an offering, its owner would nation. -

Pharmacology and Dietetics in the Bible and Talmud Fred

PHARMACOLOGY AND DIETETICS IN THE BIBLE AND TALMUD FRED ROSNER Introduction In his classic book on biblical and talmudic medicine, Julius Preuss devotes an entire chapter to materia medica and another chapter to dietetics, thereby accentuating the importance of these topics in Jewish antiquity and the middle ages. 1 Since numerous volumes could be written on either of these two vast subjects, this essay confines itself primarily to presentations of two examples of each topic. In regard to pharmacology in the Bible and Talmud, the famous balm of Gilead and the equally renowned biblical mandrakes will be discussed. As examples of dietetics, classic Jewish sources dealing with dairy products as well as chicken soup, the Jewish penicillin, will be cited. Pharmacology in Bible and Talmud One must be extremely careful in describing the pharmacology of antiquity. The entire system of dispensing drugs today is much simpler and more precise than even only a few decades ago. One need only compare the list of ingredients or length of prescriptions of one hundred years ago to a modern prescription. Medications described in the Bible and Talmud are mostly derived from the flora. However, numerous animal remedies were known to the talmudic Sages. For example, although honey was used to revive a person who fainted (? hypoglycemia), eating honey was thought to be harmful for wound healing. 2 A person with pain in the heart should suck goat's milk directly from the udder of the animal. 3 Someone bitten by a dog was given liver from that dog to eat4 as recommended by physicians in antiquity, perhaps an early form of immunotherapy. -

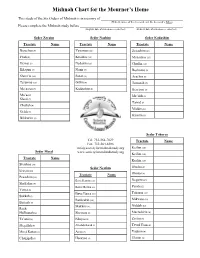

English Mishnah Chart

Mishnah Chart for the Mourner’s Home This study of the Six Orders of Mishnah is in memory of (Hebrew names of the deceased, and the deceased’s father) Please complete the Mishnah study before (English date of shloshim or yahrtzeit ) (Hebrew date of shloshim or yahrtzeit ) Seder Zeraim Seder Nashim Seder Kodashim Tractate Name Tractate Name Tractate Name Berachos (9) Yevamos (16) Zevachim (14) Peah (8) Kesubos (13) Menachos (13) Demai (7) Nedarim (11) Chullin (12) Kilayim (9) Nazir (9) Bechoros (9) Shevi’is (10) Sotah (9) Arachin (9) Terumos (11) Gittin (9) Temurah (7) Ma’asros (5) Kiddushin (4) Kereisos (6) Ma’aser Me’ilah (6) Sheni (5) Tamid (7) Challah (4) Middos (5) Orlah (3) Kinnim (3) Bikkurim (3) Seder Tohoros Tel: 732-364-7029 Tractate Name Fax: 732-364-8386 [email protected] Keilim (10) Seder Moed www.societyformishnahstudy.org Keilim (10) Tractate Name Keilim (10) Shabbos (24) Seder Nezikin Oholos (9) Eruvin (10) Tractate Name Oholos (9) Pesachim (10) Bava Kamma (10) Negaim (14) Shekalim (8) Bava Metzia (10) Parah (12) Yoma (8) Bava Basra (10) Tohoros (10) Sukkah (5) Sanhedrin (11) Mikvaos (10) Beitzah (5) Makkos (3) Niddah (10) Rosh HaShanah (4) Shevuos (8) Machshirin (6) Ta’anis (4) Eduyos (8) Zavim (5) Megillah (4) Avodah Zarah (5) Tevul Yom (4) Moed Kattan (3) Avos (5) Yadaim (4) Chagigah (3) Horayos (3) Uktzin (3) • Our Sages have said that Asher, son of the Patriarch Jacob sits at the opening to Gehinom (Purgatory), and saves [from entering therein] anyone on whose behalf Mishnah is being studied . -

Guide to Hebrew Transliteration and Rabbinic Texts

Guide to using Rabbinic texts: Transliteration issues: Hebrew has a different phonetic structure from English, and there is no universally accepted transliteration system. Therefore, the same title or word might show up in English works with diverse spellings. Here are a few things you can look for. Consonants ß The Hebrew letter b is usually an English B, but under some circumstances it is pronounced as a V. In those cases, it can be transliterated as either b, b, or v. (In German, it might even show up as a w.) ß Hebrew w can show up as either a v or a w. ß Hebrew x is an aspirated h sound, and is correctly transliterated as a h 9 (with a dot underneath). Ashkenazic Jews pronounce it as a gutteral, like the soft k (see below), and so it is often transliterated as a kh or ch. ß The Hebrew y, which is a Y consonant, might be transliterated as i or j (especially in German works). ß Similarly, the letter k is usually a simple K, but under some circumstances it is a guttural (Scottish/German) ch or kh sound, and is transliterated accordingly. ß Hebrew p can be either a P or F sound, depending on certain grammatical rules. In the latter case, it can be written as a p, p, f or ph. ß The Hebrew c is an emphatic S sound with no real equivalent in English. The correct transliteration is s,9 but Ashkenazic Jews generally pronounce it as a TZ sound, so that it will be transliterated as z, tz, ts, c or.ç. -

Jesus, the New Temple, and the New Priesthood

Letter & Spirit 4 (2008): 47–83 Jesus, the New Temple, and the New Priesthood 1 Brant Pitre 2 Our Lady of Holy Cross College Almost fifty years ago, in his excellent but often-overlooked book, The Mystery of the Temple, the great Dominican theologian Yves Congar highlighted a paradox present in the gospels—a mystery of sorts: When the gospel texts are read straight through with a view to discovering the attitude of Jesus towards the Temple and all it represented, two apparently contradictory features become immediately apparent: Jesus’ immense respect for the Temple; his very lively criticism of abuses and of formalism, yet above and beyond this, his constantly repeated assertion that the Temple is to be transcended, that it has had its day, and that it is doomed to disappear. With these words, Congar put his finger on one of the most puzzling aspects of Jesus’ relationship to the Judaism of his day. For it is of course true that the Gospels contain numerous statements of Jesus in which he esteems the Temple as the dwelling place of God, and others in which he explicitly denounces the Temple and declares that it will eventually be destroyed. For example, on the one hand, Jesus says, “he who swears by the Temple, swears by it and by him who dwells in it” (Matt. 23:21). On the other hand, he denounces the city of Jerusalem for opposing the prophets of God and says to her: “Behold, your house [the Temple] is forsaken and desolate” (Matt. 23:38). How do we explain this seeming paradox? How can Jesus both revere the Temple and at the same time declare its eventual destruction? In order to answer this question, I will focus on four aspects of the Jewish Temple that are widely known but have not been sufficiently highlighted in the his- torical study of Jesus. -

Torah from the Years of Wrath 1939-1943: the Historical Context of the Aish Kodesh

Touro Scholar Lander College of Arts and Sciences Books Lander College of Arts and Sciences 2017 Torah from the Years of Wrath 1939-1943: The Historical Context of the Aish Kodesh Henry Abramson Touro College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://touroscholar.touro.edu/lcas_books Part of the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Abramson, H. (2017). Torah from the Years of Wrath 1939-1943: The Historical Context of the Aish Kodesh. Retrieved from https://touroscholar.touro.edu/lcas_books/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Lander College of Arts and Sciences at Touro Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Lander College of Arts and Sciences Books by an authorized administrator of Touro Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Torah from the Years of Wrath 1939-1943 Torah from the Years of Wrath 1939-1943 The Historical Context of the Aish Kodesh הי׳׳ד Rabbi Kalonymus Kalmish Shapira The Rebbe of Piaseczno, also known as the Aish Kodesh (Holy Fire) Son of Rabbi Elimelekh of Grodzisk Son-in-law of Rabbi Yerahmiel Moshe of Kozienice Henry Abramson 2017 CreateSpace Edition License Notes Educational institutions may reproduce, copy and distribute portions of this book for non-commercial purposes without charge, provided appropriate citation of the source, in accordance with the Talmudic dictum of Rabbi Elazar in the name of Rabbi Hanina (Megilah 15a): “anyone who cites a teaching in the name of its author brings redemption to the world.” Copyright 2017 Henry Abramson Version 1.0 Heshvan 5778 (October 2017) Cover design by Meir Weiss and Tehilah Weiss Dedicated to the Piaseczno Rebbe and his students איך וויל זע גאר ניסט. -

Temple Israel Library

NEWELAZAR07252011 Introduction TEMPLE ISRAEL LIBRARY Is organized according to the Elazar Classification Scheme The Elazar classification scheme, first drafted in 1952 for use in the Library of the United Hebrew Schools of Detroit, Michigan, passed through several revisions and modifications and was originally published in 1962, The National Foundation for Jewish Culture assisting with the circulation of the incipient draft for comment and criticism. Wayne State University Libraries provided a grant-in-aid which prepared the manuscript for publication. The Second Edition, which was published in 1978, was revised on the basis of comments by the members of the Association of Jewish Libraries of Southern California. Rita B. Frischer and Rachel K. Glasser of Sinai Temple Blumenthal Library, and the Central Cataloging Service for Libraries of Judaica (CCS) in Los Angeles, assisted in the preparation and revision of the Third Edition. (See David H. Elazar, and Daniel J. Elazar, A Classification System for Libraries of Judaica, Northvale, N.J.: Jason Aronson Inc, 1997.) Its use has spread widely throughout the United States, Israel, and other parts of the Jewish world. Libraries of all kinds, in synagogues and community centers, in Hebrew schools. On college campuses and in research institutions, have adopted the scheme and worked with it. The system is structured around The following ten classes: 001-099 Bible and Biblical Studies 100-199 Classical Judaica: Halakhah and Midrash 200-299 Jewish Observance and Practice 300-399 Jewish Education 400-499 Hebrew, Jewish Languages and Sciences 500-599 Jewish Literature (including Fiction and Children‟s Literature) 600-699 The Jewish Community: Society and the Arts 700-799 Jewish History, Geography, Biography 800-899 Israel and Zionism 900-999 General Works ELAZAR CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM 001---099 Bible and Biblical Studies Torah, Apocrypha, Pseudepigrapha 001 Complete Bible .1 Art, Rare, Special Editions .2 Hebrew with translation .5 Polyglot Bibles .8 Combined “Old Testament” and “New Testament” The Holy Scriptures. -

Download File

Halevy, Halivni and The Oral Formation of the Babylonian Talmud Ari Bergmann Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Ari Bergmann All rights reserved ABSTRACT Halevy, Halivni and The Oral Formation of the Babylonian Talmud Ari Bergmann This dissertation is dedicated to a detailed analysis and comparison of the theories on the process of the formation of the Babylonian Talmud by Yitzhak Isaac Halevy and David Weiss Halivni. These two scholars exhibited a similar mastery of the talmudic corpus and were able to combine the roles of historian and literary critic to provide a full construct of the formation of the Bavli with supporting internal evidence to support their claims. However, their historical construct and findings are diametrically opposed. Yitzhak Isaac Halevy presented a comprehensive theory of the process of the formation of the Talmud in his magnum opus Dorot Harishonim. The scope of his work was unprecedented and his construct on the formation of the Talmud encompassed the entire process of the formation of the Bavli, from the Amoraim in the 4th century to the end of the saboraic era (which he argued closed in the end of the 6th century). Halevy was the ultimate guardian of tradition and argued that the process of the formation of the Bavli took place entirely within the amoraic academy by a highly structured and coordinated process and was sealed by an international rabbinical assembly. While Halevy was primarily a historian, David Weiss Halivni is primarily a talmudist and commentator on the Talmud itself. -

Maimonides on the Purpose of Ritual Sacrifices

religions Essay Weaning Away from Idolatry: Maimonides on the Purpose of Ritual Sacrifices Reuven Chaim Klein Independent Researcher, Beitar Illit 90500, Israel; [email protected] Abstract: This essay explores Maimonides’ explanation of the Bible’s rationale behind the ritual sacrifices, namely to help wean the Jews away from idolatrous rites. After clearly elucidating Maimonides’ stance on the topic, this essay examines his view from different angles with various possible precedents in earlier rabbinic literature for such an understanding. The essay also shows why various other Jewish commentators objected to Maimonides’ understanding and how Maimonides might respond to those critiques. Additionally, this essay also situates Maimonides’ view on sacrifices within his broader worldview of the Bible’s commandments in general as serving as a counterweight to idolatrous rituals. Keywords: sacrifices; theology; maimonides; ritual; idolatry; paganism; cult; fetishism; nahmanides; judaism; bible; midrash; talmud; rabbinics; philosophy; rationalism; polemics; mysticism; ancient near east; bible studies 1. Maimonides’ Position In his Guide for the Perplexed (3:30, 3:32), Maimonides explains that the Torah’s main objective is to eradicate the viewpoint of paganism. Thus, to truly understand the Torah’s original intent, one must be familiar with the philosophies and practices of ancient idolaters (in Maimonidean terms, this refers to practitioners of non-monotheistic religions). Citation: Klein, Reuven Chaim. 2021. Weaning Away from Idolatry: Taking this idea a step further, Maimonides seemingly assumes that ritual sacrifices Maimonides on the Purpose of Ritual are a sub-optimal form of worship, leading him to making the bold statement that the Torah Sacrifices. Religions 12: 363. https:// instituted its system of ritual sacrifices to facilitate the rejection of idolatrous practices. -

SYNOPSIS the Mishnah and Tosefta Are Two Related Works of Legal

SYNOPSIS The Mishnah and Tosefta are two related works of legal discourse produced by Jewish sages in Late Roman Palestine. In these works, sages also appear as primary shapers of Jewish law. They are portrayed not only as individuals but also as “the SAGES,” a literary construct that is fleshed out in the context of numerous face-to-face legal disputes with individual sages. Although the historical accuracy of this portrait cannot be verified, it reveals the perceptions or wishes of the Mishnah’s and Tosefta’s redactors about the functioning of authority in the circles. An initial analysis of fourteen parallel Mishnah/Tosefta passages reveals that the authority of the Mishnah’s SAGES is unquestioned while the Tosefta’s SAGES are willing at times to engage in rational argumentation. In one passage, the Tosefta’s SAGES are shown to have ruled hastily and incorrectly on certain legal issues. A broader survey reveals that the Mishnah also contains a modest number of disputes in which the apparently sui generis authority of the SAGES is compromised by their participation in rational argumentation or by literary devices that reveal an occasional weakness of judgment. Since the SAGES are occasionally in error, they are not portrayed in entirely ideal terms. The Tosefta’s literary construct of the SAGES differs in one important respect from the Mishnah’s. In twenty-one passages, the Tosefta describes a later sage reviewing early disputes. Ten of these reviews involve the SAGES. In each of these, the later sage subjects the dispute to further analysis that accords the SAGES’ opinion no more a priori weight than the opinion of individual sages. -

Beginners Guide for the Major Jewish Texts: Torah, Mishnah, Talmud

August 2001, Av 5761 The World Union of Jewish Students (WUJS) 9 Alkalai St., POB 4498 Jerusalem, 91045, Israel Tel: +972 2 561 0133 Fax: +972 2 561 0741 E-mail: [email protected] Web-site: www.wujs.org.il Originally produced by AJ6 (UK) ©1998 This edition ©2001 WUJS – All Rights Reserved The Guide To Texts Published and produced by WUJS, the World Union of Jewish Students. From the Chairperson Dear Reader Welcome to the Guide to Texts. This introductory guide to Jewish texts is written for students who want to know the difference between the Midrash and Mishna, Shulchan Aruch and Kitzur Shulchan Aruch. By taking a systematic approach to the obvious questions that students might ask, the Guide to Texts hopes to quickly and clearly give students the information they are after. Unfortunately, many Jewish students feel alienated from traditional texts due to unfamiliarity and a feeling that Jewish sources don’t ‘belong’ to them. We feel that Jewish texts ought to be accessible to all of us. We ought to be able to talk about them, to grapple with them, and to engage with them. Jewish texts are our heritage, and we can’t afford to give it up. Jewish leaders ought to have certain skills, and ethical values, but they also need a certain commitment to obtaining the knowledge necessary to ensure that they aren’t just leaders, but Jewish leaders. This Guide will ensure that this is the case. Learning, and then leading, are the keys to Jewish student leadership. Lead on! Peleg Reshef WUJS Chairperson How to Use The Guide to Jewish Texts Many Jewish students, and even Jewish student leaders, don’t know the basics of Judaism and Jewish texts. -

Jewish Folk Literature

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of Near Eastern Languages and Departmental Papers (NELC) Civilizations (NELC) 1999 Jewish Folk Literature Dan Ben-Amos University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/nelc_papers Part of the Cultural History Commons, Folklore Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, and the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons Recommended Citation Ben-Amos, D. (1999). Jewish Folk Literature. Oral Tradition, 14 (1), 140-274. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/nelc_papers/93 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/nelc_papers/93 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jewish Folk Literature Abstract Four interrelated qualities distinguish Jewish folk literature: (a) historical depth, (b) continuous interdependence between orality and literacy, (c) national dispersion, and (d) linguistic diversity. In spite of these diverging factors, the folklore of most Jewish communities clearly shares a number of features. The Jews, as a people, maintain a collective memory that extends well into the second millennium BCE. Although literacy undoubtedly figured in the preservation of the Jewish cultural heritage to a great extent, at each period it was complemented by orality. The reciprocal relations between the two thus enlarged the thematic, formal, and social bases of Jewish folklore. The dispersion of the Jews among the nations through forced exiles and natural migrations further expanded