Looking for a Career Where the Sky Is the Limit?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aeronáutica Básica Flota De Históricos Flotas Modernas ULD Flete Y Recargos

TRANSPORTE AEREO Aeronáutica básica Flota de históricos Flotas modernas ULD Flete y recargos Tipología de aviones Messerschmitt Me 323 Gigant, Alemania. 1942 Tropero más grande el avión de transporte de tropas más grande de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Se construyeron 213 unidades. Hughes H-4 Hercules,EE.UU. 1947 Lo construyó una de las empresas del magnate Howard Hughes, y era capaz de levantar 180.000 kilos. Solo se construyó uno. Armstrong Whitworth AW.660 Argosy, Reino Unido. 1959 Este transporte de carga y personal exhibía también una línea muy particular, con el fuselaje mucho más grueso en la perte frontal. Cargaba hasta 13.000 kilos y se le conocía como "The Whistling Wheelbarrow" (la carretilla silbadora Antonov An-22, Unión Soviética. 1965 Es el avión de hélice turbopropulsado más grande del mundo y el más grande de la época hasta la aparición del C-5 Galaxy estadounidense. Cargaba 80.000 kilos. Antonov 12 Se han construido más de 900 unidades civiles y militares de este transporte pesado mixto de hasta 20.000 kilos. Su capacidad para despegar y aterrizar en pistas sin asfaltar lo ha hecho muy popular en países en vías de desarrollo. Antonov An-225 Mriya, Unión Soviética. 1988 • Aparte de cargar transbordadore s espaciales, este es el avión de carga más grande y pesado del mundo. Él solo es capaz de levantar 253.820 kilos. Lockheed C-5 Galaxy, EE.UU. 1968 Dotado de un inusual sistema de carga desde la parte delantera, el C-5 es de uso exclusivo del ejército estadounidense y sigue en activo. -

Sanders Aviation to Train Pilots for Delta at Walker County Airport

Sanders Aviation to train pilots for Delta at Walker County Airport JASPER, Alabama — Working in partnership with the Delta Air Crew Training Center in Atlanta, Sanders Aviation is launching a training program that will feed a pipeline of new pilots for Delta, as well as all leading airlines. The first class in the Sanders-Delta Airline Transport Pilot Certified Training Program (ATP-CTP) is scheduled to begin Sept. 27 at Jasper’s Walker County Airport-Bevill Field. The 10-day course involves 30 hours of classroom academics, hands-on experience in full-motion flight simulators, and several hours of training in the Sanders Flight Training Center’s multi-engine airplanes. The certification course is designed to help students, mainly former military pilots, land a job as a pilot for Delta and other large airlines. “This is going to cover everything they need to know to transition from the military to the airlines,” said Jessica S. Walker, chief operating officer at Sanders Aviation. “So if they’ve been flying F-18s, F-35s or KC-135s, this is a course that focuses on how to use the first officer, how to act as a captain, how to talk to air traffic control around the world, how to use all resources possible to transition from the military life into the airline.” Delta’s partnership with Sanders Aviation comes as the Atlanta-based airline company looks to increase its pilot ranks amid retirements and an expansion of routes. During the next decade, Delta expects to hire more than 8,000 pilots to staff the daily flights it operates around the world. -

Air Travel Consumer Report

U.S. Department of Transportation Air Travel Consumer Report A Product Of The OFFICE OF AVIATION ENFORCEMENT AND PROCEEDINGS Aviation Consumer Protection Division Issued: May 2006 1 Flight Delays March 2006 12 Months Ending March 2006 1 Mishandled Baggage March 2006 January-March 2006 1 st Oversales 1 Quarter 2006 2 Consumer Complaints March 2006 (Includes Disability and January-March 2006 Discrimination Complaints) Customer Service Reports to the Dept. of Homeland Security3 March 2006 Airline Animal Incident Reports4 March 2006 1 Data collected by the Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Website: http://www.bts.gov/ 2 Data compiled by the Aviation Consumer Protection Division. Website: http://airconsumer.ost.dot.gov/ 3 Data provided by the Department of Homeland Security, Transportation Security Administration 4 Data collected by the Aviation Consumer Protection Division TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page Section Page Introduction ......................…2 Flight Delays Mishandled Baggage Explanation ......................…3 Explanation ....................…..25 Table 1 ......................…4 Ranking--Month ....................…..26 Overall Percentage of Reported Flight Ranking--YTD ..................…....27 Operations Arriving On Time, by Carrier Table 1A ......................…5 Oversales Overall Percentage of Reported Flight Explanation ....................…..28 Operations Arriving On Time and Carrier Rank, Ranking--Quarter ..................…....29 by Month, Quarter, and Data Base to Date Table 2 ......................…6 Consumer Complaints -

The Return to Air Travel Aviation in a Post-Pandemic World

The Return to Air Travel Aviation in a post-pandemic world Executive Summary COVID-19 has caused an unprecedented disruption to global travel. As of May 14th, less than 20% of people felt comfortable travelling by air. For airports and airlines, the rate at which passengers return to traveling will determine not just corporate strategy but long-term financial viability. This research characterizes general attitudes toward air travel and how people currently anticipate their Key Findings travel habits to change in the coming months and years, with the objective of determining the rate of recovery and what factors will influence it. People are concerned about the Methods have significantly impacted their jobs, health of the airport environment, but their ability to take personal trips and are also excited to return to air travel. We administered a national survey their overall happiness, with 38% of exploring how COVID-19 has impacted people reporting that restrictions on people’s perceptions of air travel on Airport strategies of continuous travel lowered their happiness either May 14, 2020 via Amazon Mechanical environmental monitoring, real-time very much or extremely. Turk (MTurk). 970 respondents met the display of environmental conditions, survey criteria and were included in the Passengers universally ranked strategies and touchless technology are analysis. Respondents were prompted that limit the risk of COVID-19 transmis- associated with increased traveler with questions relating to the impact of sion as important. While temperature confidence in the airport. travel restrictions on their life and monitoring and handwashing signage happiness, their positive and negative are the two policies most passengers Boosting traveler confidence can sentiments around returning to air expect to encounter next time they bring travelers back to air travel 6-8 travel, their concerns with various travel, continuous environmental months sooner. -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

Hypermobile Travellers

6. HYPERMOBILE TRAVELLERS Stefan Gössling, Jean-Paul Ceron, Ghislain Dubois, Michael C. Hall [a]Introduction The contribution of aviation to climate change is, with a global share of just 2 per cent of emissions of CO 2 (see chapter 2, this volume), often regarded as negligible. This perspective ignores, however, the current and expected growth in air traffic, as well as its socio-cultural drivers. Aviation is a rapidly growing sector, with annual passenger growth forecasts of 4.9 per cent in the coming 20 years (Airbus 2008) In a carbon-constrained world with the ambition to reduce absolute levels of greenhouse gas emissions and limited options to technically achieve these (see chapter 13, this volume), the growth in air traveller numbers thus indicates an emerging conflict (see also chapter 4, this volume) Moreover, it becomes increasingly clear that aviation is an activity in which comparably few people participate. With regard to international aviation, it can be estimated that only about 2-3 per cent of the world’s population fly in between any two countries over one consecutive year (Peeters et al 2006), indicating that participation in air travel is highly unequally distributed on a global scale. The vast majority of air travellers currently originate from industrialized countries, even though there are some recent trends, particularly in China and India, showing rapid growth in air travel (cf. UNWTO 2007) There is also evidence that air travel is unevenly distributed within nations, particularly those with already high levels of individual mobility. In industrialized countries there is evidence of a minority of highly mobile individuals, who account for a large share of the overall kilometres travelled, especially by air. -

Aviation Deregulation and Safety: Theory and Evidence

AVIATION DEREGULATION AND SAFETY Theory and Evidence By Leon N. Moses and Ian Savage* The popular press paints a bleak picture of contemporary aviation safety in the United States. The cover stories of Time (12 January 1987), Newsweek (27 July 1987), and Insight (26 October 1987) are of crashes and escalating numbers of near midair collisions, with allegations of improper maintenance. In the minds of the public, these allegations are confirmed by the recent record fines for irregularities imposed on airlines with household names. The popular belief, expressed for example by Nance (1986), is that the root cause is the economic deregulation of the industry in 1978. Deregulation, it is argued, has led to com petitive pressures on air carriers to reduce expenditure on safety-related items, and allowed entry into the market by inexperienced new carriers. In addition many believe that the congestion caused by the greater number of airline flights, occasioned by the substantial rise in demand since deregulation, has led to an increased probability of collision. This paper considers the evidence to date on the validity of these contentions. However, initially we will present a theoretical framework that links economic conditions and the safety performance of firms. This framework allows inferences to be drawn more easily from the various strands of evidence. THE THEORY A definition of "safety" Before we present the theory of safety provision an important semantic issue arises. Throughout the discussion we will speak of "safety" as if it were some unambiguously defined unidimensional concept. It is no such thing. Even if we were to define safety as the "probability that a trip would end in an accident", there would still be the problem that accidents vary in severity from minor damage-only incidents to major tragedies with loss of life. -

The Impact of the First Officer Qualification Ruling: Pilot Performance in Initial Training

Available online at http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/jate Journal of Aviation Technology and Engineering 5:1 (2015) 25–32 The Impact of the First Officer Qualification Ruling: Pilot Performance in Initial Training Nancy R. Shane (University of North Dakota) Abstract The intent of the First Officer Qualification (FOQ) ruling was to improve the quality of first officers flying for Part 121 carriers. In order to test this, a study was completed at a regional carrier to compare pilots hired prior to the FOQ ruling with those hired after the FOQ ruling. The study compared 232 pilots hired from 2005–2008 with 184 pilots hired from August 2013–November 2014. The pilots’ date of hire as compared to the date the FOQ ruling went into effect defined the input (Source) variable. Initial training defined the output (Success) variables. The airline name and all identifying information were removed from the data set. The pilots were compared in three areas: total flight hours, training completion and extra training events. The results of the study show that, while pilots hired after the FOQ ruling had a significantly higher number of total flight hours, that group was more likely to need additional training and less likely to successfully complete training than those who were hired prior to FOQ. The study shows that there may have been some unintended consequences of the FOQ ruling and that more extensive research is needed to confirm that these results are representative of regional carriers across the industry. Keywords: air carrier, aviation degree, first officer, first officer qualification, flight hours, flight instructor, Part 61, Part 121, pilot certification, pilot source study, pilot training, regional airline On February 12, 2009, a Colgan Airways Q400 crashed in bad weather on approach to Buffalo Niagara International Airport (National Transportation Safety Board, 2010). -

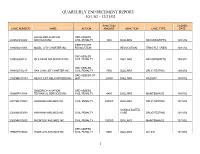

Quarterly Enforcement Report 10/1/02 - 12/31/02

QUARTERLY ENFORCEMENT REPORT 10/1/02 - 12/31/02 SANCTION CLOSED CASE NUMBER NAME ACTION AMOUNT SANCTION CASE TYPE DATE HAGELAND AVIATION ORD ASSESS 2002SO030029 SERVICES INC CIVIL PENALTY 1000 DOLLARS RECORDS/RPTS 10/01/02 CERTIFICATE 1996SO210003 MUSIC CITY CHARTER INC REVOCATION REVOCATION TRNG-FLT CREW 10/01/02 ORD ASSESS 1999SO950132 ISLA NENA AIR SERVICE INC CIVIL PENALTY 8251 DOLLARS RECORDS/RPTS 10/03/02 ORD ASSESS 1999SO730217 SAN JUAN JET CHARTER INC CIVIL PENALTY 7000 DOLLARS DRUG TESTING 10/04/02 ORD ASSESS CP 2002NM010133 HEAVY LIFT HELICOPTERS INC HMT 20000 DOLLARS HAZ MAT 10/07/02 GOODRICH AVIATION ORD ASSESS 1999WP910064 TECHNICAL SERVICES INC CIVIL PENALTY 4400 DOLLARS MAINTENANCE 10/07/02 2001NM910061 HAWAIIAN AIRLINES INC CIVIL PENALTY 250000 DOLLARS DRUG TESTING 10/10/02 CONSOLIDATED 2002NM030008 HAWAIIAN AIRLINES INC CIVIL PENALTY CASE DRUG TESTING 10/10/02 2002NM030032 FRONTIER AIRLINES INC CIVIL PENALTY 100000 DOLLARS MAINTENANCE 10/10/02 ORD ASSESS 1996WP010042 FRONTIER AIRLINES INC CIVIL PENALTY 5000 DOLLARS OTHER 10/10/02 1 QUARTERLY ENFORCEMENT REPORT 10/1/02 - 12/31/02 SANCTION CLOSED CASE NUMBER NAME ACTION AMOUNT SANCTION CASE TYPE DATE ORD ASSESS 2001WP270114 JRS ENTERPRISES INC CIVIL PENALTY 1500 DOLLARS TYPE DESGN DATA 10/15/02 ORD ASSESS 2002GL070037 HOSES UNLIMITED CIVIL PENALTY 8562 DOLLARS MAINTENANCE 10/15/02 CAPITAL AIRCRAFT ORD ASSESS 2002NM130029 ELECTRONICS INC CIVIL PENALTY 1000 DOLLARS AIRCRAFT ALTR 10/15/02 CP COMPROMIS 1999SO250107 EXECUTIVE FLIGHT INC NO FINDING 10000 DOLLARS MAINTENANCE 10/15/02 -

168 Subpart P—Aircraft Dispatcher Qualifications and Duty Time

§ 121.445 14 CFR Ch. I (1–1–12 Edition) § 121.445 Pilot in command airport (3) By completing the training pro- qualification: Special areas and air- gram requirements of appendix G of ports. this part. (a) The Administrator may deter- [Doc. No. 17897, 45 FR 41594, June 19, 1980] mine that certain airports (due to items such as surrounding terrain, ob- § 121.447 [Reserved] structions, or complex approach or de- parture procedures) are special airports § 121.453 Flight engineer qualifica- requiring special airport qualifications tions. and that certain areas or routes, or (a) No certificate holder may use any both, require a special type of naviga- person nor may any person serve as a tion qualification. flight engineer on an airplane unless, (b) Except as provided in paragraph within the preceding 6 calendar (c) of this section, no certificate holder months, he has had at least 50 hours of may use any person, nor may any per- flight time as a flight engineer on that son serve, as pilot in command to or type airplane or the certificate holder from an airport determined to require or the Administrator has checked him special airport qualifications unless, on that type airplane and determined within the preceding 12 calendar that he is familiar and competent with months: all essential current information and (1) The pilot in command or second in operating procedures. command has made an entry to that (b) A flight check given in accord- airport (including a takeoff and land- ance with § 121.425(a)(2) satisfies the re- ing) while serving as a pilot flight quirements of paragraph (a) of this sec- crewmember; or tion. -

Electric Airports

Electric Airports In the next few years, it is highly likely that the global aircraft fleet will undergo a transformative change, changing air travel for everyone. This is a result of advances in battery technology, which are making the viability of electric aircraft attractive to industry leaders and startups. The reasons for switching from a fossilfueled to electric powertrain are not simply environmental, though aircraft do currently contribute around 3% of global carbon dioxide emissions [1]. Electric aircraft will provide convenient, comfortable, cheap and fast transportation for all. This promise provides a powerful incentive for large companies such as Airbus and many small startups to work on producing compelling electric aircraft. There are a number of fundamental characteristics that make electric aircraft appealing. The most intuitive is that they are predicted to produce very little noise, as the propulsion system does not rely on violent combustion [2]. This makes flying much quieter for both passengers and people around airports. As they do not need oxygen for burning jet fuel, they can fly much higher, which in turn will make them faster than today’s aircraft as air resistance decreases with altitude [3]. The most exciting characteristic is that electric aircraft could make vertical takeoff and landing, or VTOL, flight a possibility for everyone. Aircraft currently take off using a long runway strip, gaining speed until there is enough airflow over the wings to fly. It obviously doesn’t have to be this way, as helicopters have clearly demonstrated. You can just take off vertically. Though helicopters are far too expensive and slow for us to use them as airliners. -

REJECTED CONTRACTS Non-Debtor Party Contract

REJECTED CONTRACTS Non-Debtor Party Contract Description ACG 1030 Higgins LLC Office Lease Dated October 1, 2002 between Atlantic Coast Airlines and ACG 1030 Higgins LLC ACG 1030 Higgins LLC Rider 1 to Lease Agreement between Atlantic Coast Airlines and ACG 1030 Higgins LLC dated 1/15/2003 ACG 1030 Higgins LLC Rider 2 to Lease Agreement between Atlantic Coast Airlines and ACG 1030 Higgins LLC signed 10/1/2002 ACG 1030 Higgins, LLC Consent to Assignment among Atlantic Coast Airlines, ACG 1030 Higgins, LLC, and Air Wisconsin Airlines Corporation dated 12/1/2003 Aero Snow Removal a Division of East Coast Amendment I to Snow Removal Agreement between Atlantic Sweeping Inc Coast Airlines and Aero dated 11/1/2004 Snow Removal Agreement between Atlantic Coast Airlines, Inc. Aero Snow Removal, a division of East Coast dba United Express and Aero Snow Removal, a division of East Sweeping, Corp. Coast Sweeping, Corp. signed 11/19/1999 Airport Group International Agreement for Airport Services between Atlantic Coast Airlines dba Independence Air and Airport Group International dated 6/15/2004 Airport Group International Agreement for Into-Plane Fueling Services between Atlantic Coast Airlines dba Independence Air and Airport Group International Airline Use and Lease Agreement between Independence Air and Albany County Airport Authority Albany County Airport Authority dated 6/1/2004 Agreement Regarding Boarding Assistance between Atlantic Albany International Airport Coast Airlines and Albany International Airport Amadeus Global Travel Distribution, SA Amadeus AIS Agreement for Airlines between Independence Air, Inc. and Amadeus Global Travel Distribution, SA dated 2/1/2005 Amadeus Global Travel Distribution, SA Amadeus Instant Marketing Agreement between Independence Air, Inc.