The Critical Shoulder Angle As a Diagnostic Measure for Osteoarthritis and Rotator Cuff Pathology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List: Bones & Bone Markings of Appendicular Skeleton and Knee

List: Bones & Bone markings of Appendicular skeleton and Knee joint Lab: Handout 4 Superior Appendicular Skeleton I. Clavicle (Left or Right?) A. Acromial End B. Conoid Tubercle C. Shaft D. Sternal End II. Scapula (Left or Right?) A. Superior border (superior margin) B. Medial border (vertebral margin) C. Lateral border (axillary margin) D. Scapular notch (suprascapular notch) E. Acromion Process F. Coracoid Process G. Glenoid Fossa (cavity) H. Infraglenoid tubercle I. Subscapular fossa J. Superior & Inferior Angle K. Scapular Spine L. Supraspinous Fossa M. Infraspinous Fossa III. Humerus (Left or Right?) A. Head of Humerus B. Anatomical Neck C. Surgical Neck D. Greater Tubercle E. Lesser Tubercle F. Intertubercular fossa (bicipital groove) G. Deltoid Tuberosity H. Radial Groove (groove for radial nerve) I. Lateral Epicondyle J. Medial Epicondyle K. Radial Fossa L. Coronoid Fossa M. Capitulum N. Trochlea O. Olecranon Fossa IV. Radius (Left or Right?) A. Head of Radius B. Neck C. Radial Tuberosity D. Styloid Process of radius E. Ulnar Notch of radius V. Ulna (Left or Right?) A. Olecranon Process B. Coronoid Process of ulna C. Trochlear Notch of ulna Human Anatomy List: Bones & Bone markings of Appendicular skeleton and Knee joint Lab: Handout 4 D. Radial Notch of ulna E. Head of Ulna F. Styloid Process VI. Carpals (8) A. Proximal row (4): Scaphoid, Lunate, Triquetrum, Pisiform B. Distal row (4): Trapezium, Trapezoid, Capitate, Hamate VII. Metacarpals: Numbered 1-5 A. Base B. Shaft C. Head VIII. Phalanges A. Proximal Phalanx B. Middle Phalanx C. Distal Phalanx ============================================================================= Inferior Appendicular Skeleton IX. Os Coxae (Innominate bone) (Left or Right?) A. -

Chapter 5 Upper Limb Anatomy Bones and Joints

Chapter 5 Upper limb anatomy Bones and joints Scapula Costal Surface The costal (anterior) surface of the scapula faces the ribcage. It contains a large concave depression over most of its surface, known as the subscapular fossa. The subscapularis (rotator cuff muscle) originates from this fossa. Originating from the superolateral surface of the costal scapula is the coracoid process. It is a hook-like projection, which lies just underneath the clavicle. Three muscles attach to the coracoid process: the pectoralis minor, coracobrachialis, the short head of biceps brachii. Acromion Coracoid process Glenoid fossa Subscapular fossa © teachmeanatomy Lateral surface • Glenoid fossa - a shallow cavity, located superiorly on the lateral border. It articulates with the head of the humerus to form the glenohumeral (shoulder) joint. • Supraglenoid tubercle - a roughening immediately superior to the glenoid fossa. The place of attachment of the long head of the biceps brachii. • Infraglenoid tubercle - a roughening immediately inferior to the glenoid fossa. The place of attachment of the long head of the triceps brachii. Supraglenoid tubercle Glenoid fossa Infraglenoid tubercle gn teachmeanatomy Posterior surface • Spine - the most prominent feature of the posterior scapula. It runs transversely across the scapula, dividing the surface into two. • Acromion - projection of the spine that arches over the glenohumeral joint and articulates with the clavicle at the acromioclavicular joint. • Infraspinous fossa - the area below the spine of the scapula, it displays a convex shape. The infraspinatus muscle originates from this area. • Supraspinous fossa - the area above the spine of the scapula, it is much smaller than the infraspinous fossa, and is more convex in shape.The supraspinatus muscle originates from this area. -

Bone Limb Upper

Shoulder Pectoral girdle (shoulder girdle) Scapula Acromioclavicular joint proximal end of Humerus Clavicle Sternoclavicular joint Bone: Upper limb - 1 Scapula Coracoid proc. 3 angles Superior Inferior Lateral 3 borders Lateral angle Medial Lateral Superior 2 surfaces 3 processes Posterior view: Acromion Right Scapula Spine Coracoid Bone: Upper limb - 2 Scapula 2 surfaces: Costal (Anterior), Posterior Posterior view: Costal (Anterior) view: Right Scapula Right Scapula Bone: Upper limb - 3 Scapula Glenoid cavity: Glenohumeral joint Lateral view: Infraglenoid tubercle Right Scapula Supraglenoid tubercle posterior anterior Bone: Upper limb - 4 Scapula Supraglenoid tubercle: long head of biceps Anterior view: brachii Right Scapula Bone: Upper limb - 5 Scapula Infraglenoid tubercle: long head of triceps brachii Anterior view: Right Scapula (with biceps brachii removed) Bone: Upper limb - 6 Posterior surface of Scapula, Right Acromion; Spine; Spinoglenoid notch Suprspinatous fossa, Infraspinatous fossa Bone: Upper limb - 7 Costal (Anterior) surface of Scapula, Right Subscapular fossa: Shallow concave surface for subscapularis Bone: Upper limb - 8 Superior border Coracoid process Suprascapular notch Suprascapular nerve Posterior view: Right Scapula Bone: Upper limb - 9 Acromial Clavicle end Sternal end S-shaped Acromial end: smaller, oval facet Sternal end: larger,quadrangular facet, with manubrium, 1st rib Conoid tubercle Trapezoid line Right Clavicle Bone: Upper limb - 10 Clavicle Conoid tubercle: inferior -

Trapezius Origin: Occipital Bone, Ligamentum Nuchae & Spinous Processes of Thoracic Vertebrae Insertion: Clavicle and Scapul

Origin: occipital bone, ligamentum nuchae & spinous processes of thoracic vertebrae Insertion: clavicle and scapula (acromion Trapezius and scapular spine) Action: elevate, retract, depress, or rotate scapula upward and/or elevate clavicle; extend neck Origin: spinous process of vertebrae C7-T1 Rhomboideus Insertion: vertebral border of scapula Minor Action: adducts & performs downward rotation of scapula Origin: spinous process of superior thoracic vertebrae Rhomboideus Insertion: vertebral border of scapula from Major spine to inferior angle Action: adducts and downward rotation of scapula Origin: transverse precesses of C1-C4 vertebrae Levator Scapulae Insertion: vertebral border of scapula near superior angle Action: elevates scapula Origin: anterior and superior margins of ribs 1-8 or 1-9 Insertion: anterior surface of vertebral Serratus Anterior border of scapula Action: protracts shoulder: rotates scapula so glenoid cavity moves upward rotation Origin: anterior surfaces and superior margins of ribs 3-5 Insertion: coracoid process of scapula Pectoralis Minor Action: depresses & protracts shoulder, rotates scapula (glenoid cavity rotates downward), elevates ribs Origin: supraspinous fossa of scapula Supraspinatus Insertion: greater tuberacle of humerus Action: abduction at the shoulder Origin: infraspinous fossa of scapula Infraspinatus Insertion: greater tubercle of humerus Action: lateral rotation at shoulder Origin: clavicle and scapula (acromion and adjacent scapular spine) Insertion: deltoid tuberosity of humerus Deltoid Action: -

The Elbow and Radioulnar Joints

6/5/2017 The Elbow and Radioulnar Joints Bones Humerus trochlea of the humerus capitulum: spherical knob on lateral side medial and lateral epicondyle Ulnar Trochlear notch of ulna Olecranon Process on posterior aspect radial notch coronoid process ulnar tuberosity Radius Head radial tuberosity The Elbow Joint Classified as a ginglymus (hinge) joint The ELBOW consists of 2 joints: humeroulnar olecranon process of the ulnar distal aspect of humerus radiohumeral radial head has small amount of articulation with humerus (capitulum) 1 6/5/2017 Proximal Radioulnar Joint Proximal radioulnar joint articulation between radius and ulnar not part of “hinge” joint trochoid (pivot) joint allows for forearm pronation/supination Movements Elbow Flexion Extension Forearm movements about the Proximal Radioulnar joint Supination: Lateral rotation Pronation: Medial Rotation Muscles Anterior Posterior Biceps brachii Triceps brachii Brachialis Anconeus Brachioradialis Supinator Pronator teres Pronator quadratus 2 6/5/2017 Muscles Elbow Flexors biceps brachii brachialis brachioradialis pronator teres Muscles Elbow Extensors triceps brachii anconeus Forearm Pronators pronator teres pronator quadratus brachioradialis* Muscles Forarm Supinators supinator biceps brachii brachioradialis* 3 6/5/2017 Anconeus (p56) Origin posterior surface of lateral epicondyle of humerus Insertion ulna, posterior surface of olecranon process Action elbow extension Biceps Brachii (p 57) Origin: long head: supraglenoid tubercle -

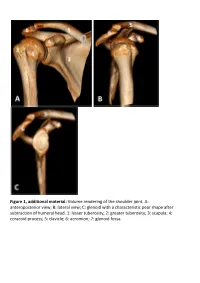

Glenoid with a Characteristic Pear Shape After Subtraction of Humeral Head

Figure 1, additional material: Volume rendering of the shoulder joint. A: anteroposterior view; B: lateral view; C: glenoid with a characteristic pear shape after subtraction of humeral head. 1: lesser tuberosity; 2: greater tuberosity; 3: scapula; 4: coracoid process; 5: clavicle; 6: acromion; 7: glenoid fossa. Figure 2, additional material: Schematic illustration of simplified shoulder anatomy. LHBT: Long head of biceps tendon; SGHL: Superior glenohumeral ligament. Trapezoid ligament and conoid ligament forming the coracoclavicular ligament. Figure 3, additional material: (A) axial, (B) sagittal oblique and (C) coronal oblique MR anatomy of the shoulder. PD-weighted sections obtained with 3 Tesla device. 1: Acromion, 2: Clavicle, 3: Acromioclavicular joint, 4: Lesser tuberosity, 5: Greater tuberosity, 6: Bicipital groove, 7: Anatomical neck, 8: Glenoid fossa/glenohumeral joint, 9: Scapula, 10: Scapular neck, 11: Suprascapular notch, 12: Coracoid process, 13: Deltoid, 14: Infraspinatus muscle, 15: Subscapularis muscle, 16: Subscapularis tendon, 17: Teres minor tendon, 18: Long head of biceps tendon, 19: Anterior labrum, 20: Posterior labrum, 21: Middle glenohumeral ligament, 22: Suprascapular nerve, 23: Inferior glenohumeral ligament/capsule, 24: Teres minor muscle, 25: Rib, 26: Humeral diaphysis, 27: Supraspinatus tendon, 28: Infraspinatus tendon, 29: Long head of biceps muscle, 30: Lateral head of triceps muscle, 31: Coracoacromial ligament, 32: Subacromial bursa, 33: Humeral head, 34: Pectoralis major muscle, 35: Coracobrachialis -

Lab Activity 9

Lab Activity 9 Appendicular Skeleton Martini Chapter 8 Portland Community College BI 231 Appendicular Skeleton • Upper & Lower extremities • Shoulder Girdle • Pelvic Girdle 2 Humerus 3 Humerus: Proximal End Greater tubercle Lesser tubercle Head: Above the epiphyseal line Anatomical Neck Surgical neck Intertubercular groove Anterior Medial Posterior4 Deltoid Tuberosity 5 Radial Groove 6 Trochlea (Distal Humerus) Anterior Posterior Anterior Posterior 7 Capitulum (Distal Humerus) Anterior Posterior Anterior Posterior 8 Olecranon Fossa (Distal Humerus) Anterior Posterior Anterior Posterior 9 Medial Epicondyle (Distal Humerus) Anterior Posterior Anterior Posterior 10 Lateral Epicondyle (Distal Humerus) Anterior Posterior Anterior Posterior 11 Radial Fossa (Distal Humerus) Anterior Posterior Anterior Posterior 12 Coronoid Fossa (Distal Humerus) Anterior Posterior Anterior Posterior 13 Lateral Supracondylar Ridge (Distal Humerus) Anterior Posterior Anterior Posterior 14 Medial Supracondylar Ridge (Distal Humerus) Anterior Posterior Anterior Posterior 15 Humerus: Distal End/Anterior Medial Lateral Supracondylar Supracondylar Ridge Ridge Coronoid Fossa Radial fossa Lateral Medial Epicondyle Epicondyle Capitulum Trochlea 16 Humerus: Distal End/Posterior Olecranon Fossa Medial Epicondyle Lateral Epicondyle Trochlea 17 Radius • “Rotates” • On the thumb side of the forearm 18 Radius: Head 19 Radial Tuberosity 20 Ulnar Notch of the Radius 21 Ulnar Notch of the Radius 22 Radius: Interosseous Ridge 23 Styloid Process of the Radius 24 Radius Distal Anterior -

Upper Extremity Scapula

Lab 6 FUNCTIONAL HUMAN ANATOMY LAB #6 UPPER/LOWER EXTREMITY OSTEOLOGY OSTEOLOGY: UPPER EXTREMITY SCAPULA: Borders: Medial (Vertebral) - most superior aspect called the Superior angle Lateral - most inferior aspect called the inferior angle Fossa: Supraspinous fossa Infraspinous fossa Subscapular fossa Glenoid fossa Other Features: acromion process coracoid process scapular spine scapular notch infraglenoid tubercle - located at the bottom of the glenoid fossa supraglenoid tubercle - located at the top of the glenoid fossa Note: the shape of the Glenoid fossa suggests that shoulder stability is heavily reliant on connective tissues surrounding the joint to prevent dislocation CLAVICLE: sternal end - blunt, articulates with the Manubrium acromial end - flat/bladelike, articulates with the Acromium process HUMERUS: head greater tubercle lesser tubercle interturbicular (bicipital) groove - located between the tubercles deltoid tuberosity shaft medial/lateral epicondyles capitulum - the part of the distal condyle that articulates with the Radius trochlea - the part of the distal condyle that articulates with the Ulna olecranon fossa coronoid fossa ULNA: 1 Lab 6 coronoid process olecranon process trochlear notch ulnar tuberosity body head (distal end) radial notch - where the proximal end of the radius articulates interosseous border (lateral side) styloid process RADIUS: body neck head (proximal end) radial tuberosity anterior oblique line interosseous border styloid process CARPAL BONES # of rows? # of bones? Which carpal primarily articulates -

Shoulder Anatomy

ShoulderShoulder AnatomyAnatomy www.fisiokinesiterapia.biz ShoulderShoulder ComplexComplex BoneBone AnatomyAnatomy ClavicleClavicle – Sternal end – Acromion end ScapulaScapula Acromion – Surfaces end Sternal Costal end Dorsal – Borders – Angles ShoulderShoulder ComplexComplex BoneBone AnatomyAnatomy Scapula 1. spine 2. acromion 3. superior border 4. supraspinous fossa 5. infraspinous fossa 6. medial (vertebral) border 7. lateral (axillary) border 8. inferior angle 9. superior angle 10. glenoid fossa (lateral angle) 11. coracoid process 12. superior scapular notch 13 subscapular fossa 14. supraglenoid tubercle 15. infraglenoid tubercle ShoulderShoulder ComplexComplex BoneBone AnatomyAnatomy HumerousHumerous – head – anatomical neck – greater tubercle – lesser tubercle – greater tubercle – lesser tubercle – intertubercular sulcus (AKA bicipital groove) – deltoid tuberosity ShoulderShoulder ComplexComplex BoneBone AnatomyAnatomy HumerousHumerous – Surgical Neck – Angle of Inclination 130-150 degrees – Angle of Torsion 30 degrees posteriorly ShoulderShoulder ComplexComplex ArticulationsArticulations SternoclavicularSternoclavicular JointJoint – Sternal end of clavicle with manubrium/ 1st costal cartilage – 3 degree of freedom – Articular Disk – Ligaments Capsule Anterior/Posterior Sternoclavicular Ligament Interclavicular Ligament Costoclavicular Ligament ShoulderShoulder ComplexComplex ArticulationsArticulations AcromioclavicularAcromioclavicular JointJoint – 3 degrees of freedom – Articular Disk – Ligaments Superior/Inferior -

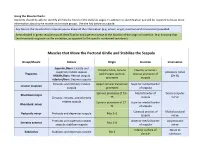

Muscle Charts: Students Should Be Able to Identify All Muscles Listed on the Daily Lab Pages

Using the Muscle Charts: Students should be able to identify all muscles listed on the daily lab pages. In addition to identification you will be required to know more information about some muscle and muscle groups. Use the key below as a guide. Any box on the muscle chart requires you to know all the information (e.g. action, origin, insertion and innervation) provided. Areas shaded in green require muscle identification and a general sense of the location of the origin or insertion. (e.g. knowing that the rhomboids originate on the vertebrae, as opposed to the specific numbered vertebrae). Muscles that Move the Pectoral Girdle and Stabilize the Scapula Group/Muscle Actions Origin Insertion Innervation Superior fibers: Elevate and Occipital bone, cervical Clavicle; acromion superiorly rotate scapula Accessory nerve Trapezius and thoracic spinous process and spine of Middle fibers: Retract scapula (CN XI) processes scapula Inferior fibers: Depress scapula Elevates and inferiorly rotates Upper cervical transverse Superior medial border Levator scapulae scapula processes of scapula Spinous processes of T2– Medial border of Dorsal scapular Rhomboid major Elevates, retracts, and inferiorly T5 scapula nerve rotates scapula Spinous processes of C7– Superior medial border Rhomboid minor T1 of scapula Coracoid process of Medial pectoral Pectoralis minor Protracts and depresses scapula Ribs 3–5 scapula nerve Protracts and superiorly rotates Anterior medial border Long thoracic Serratus anterior Ribs 1–8 scapula; stabilizes scapula of scapula nerve -

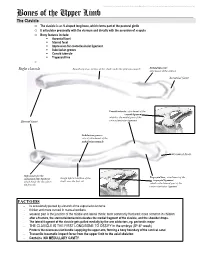

Bones of the Upper Limb

This document was created by Alex Yartsev ([email protected]); if I have used your data or images and forgot to reference you, please email me. Bones of the Upper Limb The Clavicle o The clavicle is an S-shaped long bone, which forms part of the pectoral girdle o It articulates proximally with the sternum and distally with the acromion of scapula o Bony features include: . Acromial facet . Sternal facet . Impression for costoclavicular ligament . Subclavian groove . Conoid tubercle . Trapezoid line o Right clavicle Smooth superior surface of the shaft, under the platysma muscle Deltoid tubercle: attachment of the deltoid Acromial facet Conoid tubercle, attachment of the conoid ligament which is the medial part of the Sternal facet coracoclavicular ligament Subclavian groove: site of attachment of the subclavius muscle Acromial facet Impression for the Trapezoid line, attachment of the costoclavicular ligament Rough inferior surface of the trapezoid ligament which binds the clavicle to shaft, over the first rib which is the lateral part of the the first rib coracoclavicular ligament FACTOIDS - Its occasionally pierced by a branch of the supraclavicular nerve - thicker and more curved in manual workers - weakest part is the junction of the middle and lateral thirds: most commonly fractured; more common in children - after a fracture, the sternocleidomastoid elevates the medial fragment of the clavicle, and the shoulder drops. - The lateral fragment of the clavicle gets pulled medially by the arm adductors, eg. pectoralis major - THE CLAVICLE IS THE FIRST LONG BONE TO OSSIFY in the embryo (5th-6th week) - Protects the neurovascular bundle supplying the upper arm, forming a bony boundary of the cervical canal - Transmits traumatic impact force from the upper limb to the axial skeleton - Contains NO MEDULLARY CAVITY - This document was created by Alex Yartsev ([email protected]); if I have used your data or images and forgot to reference you, please email me. -

Lecture (7) Arm and Elbow.Pdf

Arm and elbow Musculoskeletal block- Anatomy-lecture 7 Editing file Color guide : Objectives Only in boys slides in Blue Only in girls slides in Purple ✓ Describe the attachments, actions and innervations of: important in Red a. Biceps brachii Doctor note in Green b. Coracobrachialis Extra information in Grey c. Brachialis d. Triceps brachii ✓ Define the boundaries of the cubital fossa and enumerate its contents. ✓ Demonstrate the following features of the elbow joint: a. Articulating bones b. Capsule c. Lateral & medial collateral ligaments d. Synovial membrane ✓ Demonstrate the movements; flexion and extension of the elbow. ✓ List the main muscles producing the above movements. ✓ Define the boundaries of the cubital fossa and enumerate its contents. Shoulder THE ARM: Posterior Anterior An aponeurotic sheet separating various view muscles of the upper limbs, including lateral A R M R A view and medial humeral septa. Elbow - The lateral and medial intermuscular septa Arm Humerus divide the distal part of the arm into two compartments Lateral Medial intermuscular intermuscular septum septum Neurovascular skin Anterior Posterior bundle (flexor compartment) (extensor compartment) Fascia Humerus 1-Anterior Fascial Compartment: Note: the radial and ulnar nerves begin in the anterior compartment then pierce the intermuscular septum and enter the posterior compartment Radial Brachialis Ulnar Median Biceps Basilic vein brachii Brachial Musculocutaneous artery Coracobrachialis 2. Blood 3. Nerves 1. muscles vessels Muscles Of Anterior Compartment Muscles Biceps Brachii Coracobrachialis Brachialis -Long Head (lateral head) from supraglenoid tubercle of Tip of the coracoid Origin scapula (intracapsular) process of scapula (with Front of the lower half -Short Head from the tip of coracoid process of scapula short head of biceps of humerus -The two heads join in the middle of the arm brachii) -Into the posterior part of the radial tuberosity.