Shining Light on the Response to Child Sexual Abuse and Exploitation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pakistan Floods: After the Deluge & the Future of Migration?

Winter 2010 Pakistan Floods: After the Deluge & The Future of Migration? Winter 2010 ISSN 1813-2855 Editor-In-Chief 3 Editorial Jean-Philippe Chauzy 4 Editors Jemini Pandya 4 Pakistan – After the Deluge Chris Lom Niurka Piñeiro Jared Bloch 8 Mass Communications 8 Layout Programme Talks and Listens to Valerie Hagger Joseph Rafanan Pakistan’s Flood Victims Cover Photo Asim Hafeez/OnAsia 11 Giving Voice to Haiti’s © IOM 2010 - MPK0304 11 Earthquake Victims Migration is published twice a year in English, French and Spanish. All correspondence 14 In Search of Normal: Thoughts and inquiries concerning this publication should be sent to: about Haiti after the Earthquake 14 International Organization for Migration (IOM) PO Box 71 17 Helping the Lost Youth CH Geneva 19 Switzerland of Tanzania Tel.: +41 22 717 91 11 Fax: +41 22 798 61 50 17 E-mail: [email protected] The Silent Plight of Migrant Migration is available online 23 on the IOM website: Farm Workers in South Africa http://www.iom.int IOM is committed to the 25 Tehnology, Vigilance and Sound 25 principle that humane and Judgement – Managing the Dominican orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As Republic’s Borders an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts 28 with its partners in the 28 Biometric Passport and Indentification international community Card: Armenia Enters the Digital Age to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration 30 Shedding Light on South-South issues; encourage social Migration to Aid Development and economic development 30 through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1970S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1970s Page 130 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1970 25 Or 6 To 4 Everything Is Beautiful Lady D’Arbanville Chicago Ray Stevens Cat Stevens Abraham, Martin And John Farewell Is A Lonely Sound Leavin’ On A Jet Plane Marvin Gaye Jimmy Ruffin Peter Paul & Mary Ain’t No Mountain Gimme Dat Ding Let It Be High Enough The Pipkins The Beatles Diana Ross Give Me Just A Let’s Work Together All I Have To Do Is Dream Little More Time Canned Heat Bobbie Gentry Chairmen Of The Board Lola & Glen Campbell Goodbye Sam Hello The Kinks All Kinds Of Everything Samantha Love Grows (Where Dana Cliff Richard My Rosemary Grows) All Right Now Groovin’ With Mr Bloe Edison Lighthouse Free Mr Bloe Love Is Life Back Home Honey Come Back Hot Chocolate England World Cup Squad Glen Campbell Love Like A Man Ball Of Confusion House Of The Rising Sun Ten Years After (That’s What The Frijid Pink Love Of The World Is Today) I Don’t Believe In If Anymore Common People The Temptations Roger Whittaker Nicky Thomas Band Of Gold I Hear You Knocking Make It With You Freda Payne Dave Edmunds Bread Big Yellow Taxi I Want You Back Mama Told Me Joni Mitchell The Jackson Five (Not To Come) Black Night Three Dog Night I’ll Say Forever My Love Deep Purple Jimmy Ruffin Me And My Life Bridge Over Troubled Water The Tremeloes In The Summertime Simon & Garfunkel Mungo Jerry Melting Pot Can’t Help Falling In Love Blue Mink Indian Reservation Andy Williams Don Fardon Montego Bay Close To You Bobby Bloom Instant Karma The Carpenters John Lennon & Yoko Ono With My -

Kentucky Ancestors Genealogical Quarterly of The

Vol. 43, No. 1 Autumn 2007 Kentucky Ancestors genealogical quarterly of the Sleettown: The Birth Oral History and of a Community Genealogy: Yes, There is Something For You! Revolutionary War Rev. John “Raccoon” Warrants Database Smith Marriages Vol. 43, No. 1 Autumn 2007 Kentucky Ancestors genealogical quarterly of the Don Rightmyer, Editor Dan Bundy, Graphic Design kentucky ancestors Betty Fugate, Membership Coordinator Governor Steven L. Beshear, Chancellor Robert M. "Mike" Duncan, President Robert E. Rich, 1st Vice President Bill Black, Jr., 2nd Vice President khs officers Sheila M. Burton, 3rd Vice President Walter A. Baker Richard Frymire Yvonne Baldwin Ed Hamilton William F. Brashear II John Kleber Terry Birdwhistell Ruth A. Korzenborn J. McCauley Brown Karen McDaniel Bennett Clark Ann Pennington William Engle Richard Taylor Charles English J. Harold Utley executive comittee Martha R. Francis Kent Whitworth, Executive Director Marilyn Zoidis, Assistant Director director’s office James E. Wallace, KHS Foundation Director Warren W. Rosenthal, President Dupree, Jo M. Ferguson, Ann Rosen- John R. Hall, 1st Vice President stein Giles, Frank Hamilton, Jamie Henry C. T. Richmond III, Hargrove, Raymond R. Hornback, 2nd Vice President Elizabeth L. Jones, James C. Klotter, Kent Whitworth, Secretary Crit Luallen, James H. “Mike” Mol- James Shepherd, Treasurer loy, Maggy Patterson, Erwin Roberts, Martin F. Schmidt, Gerald L. Smith, Ralph G. Anderson, Hilary J. Alice Sparks, Charles Stewart, John Boone, Lucy A. Breathitt, Bruce P. Stewart, William Sturgill, JoEtta Y. Cotton, James T. Crain Jr., Dennis Wickliffe, Buck Woodford foundation board Dorton, Clara Dupree, Thomas research and interpretation Nelson L. Dawson, Director Kentucky Ancestors (ISSN-0023-0103) is published quarterly by the Kentucky Historical Society and is distributed free to Society members. -

Shadows in the Field Second Edition This Page Intentionally Left Blank Shadows in the Field

Shadows in the Field Second Edition This page intentionally left blank Shadows in the Field New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology Second Edition Edited by Gregory Barz & Timothy J. Cooley 1 2008 1 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright # 2008 by Oxford University Press Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Shadows in the field : new perspectives for fieldwork in ethnomusicology / edited by Gregory Barz & Timothy J. Cooley. — 2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-532495-2; 978-0-19-532496-9 (pbk.) 1. Ethnomusicology—Fieldwork. I. Barz, Gregory F., 1960– II. Cooley, Timothy J., 1962– ML3799.S5 2008 780.89—dc22 2008023530 135798642 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper bruno nettl Foreword Fieldworker’s Progress Shadows in the Field, in its first edition a varied collection of interesting, insightful essays about fieldwork, has now been significantly expanded and revised, becoming the first comprehensive book about fieldwork in ethnomusicology. -

El Grito Del Bronx 1

EL GRITO DEL BRONX 1 EL GRITO DEL BRONX (formerly known as CRY OF THE BRONX) Cast Of Characters 1977: JESÚS COLÓN—14, a boy nurtured by rage MAGDALENA COLÓN—12, his sister, tense & nervous. She walks with a cast on her right leg. MARIA COLÓN—40, their mother, very tired. JOSÉ COLÓN—45, their father, very hungry. Voice of a MALE TV NEWSCASTER Voice of a FEMALE TV NEWSCASTER Voice of a PUERTO RICAN MAN on TV 1991: PAPO—28, an inmate on death row. He is gaunt and pale. The adult JESÚS. LULU—26, a poet; the adult MAGDALENA. She has a slight limp when she walks. The GUY NEXT DOOR—PAPO’s neighbor on death row; a shadowy figure. All we see of him is his hands which change from scene to scene, sometimes black sometimes white, sometimes old, etc. MARIA— PAPO & LULU's MOTHER—54, in mourning. *FIRST GAS STATION ATTENDANT—a white man in his 20s. *LAST GAS STATION ATTENDANT—a white man in his 20s. *AND ALL OTHER GAS STATION ATTENDANTS—white men in their 20s. *All played by the same actor, his voice sometimes amplified and altered. ELIZABETH the LAST GAS STATION ATTENDANT’S MOTHER—a white woman from rural Kentucky, in her 40s in mourning. ED—28, a journalist. Jewish-american. SARAH, ELECTROCUTED BOY's MOTHER—a woman in mourning, African-american, 30s. TIME: On LULU's October wedding day in 1991, with some moments from the past also revisted between the years 1977 & 1991. PLACE: The Bronx, New York—in a 1st floor apartment in a five-story walk-up, and in a rubble-filled alley behind the building; Death Row in an Ohio Federal Prison—PAPO’s cell; Darien, CT—in ED & LULU’s studio apartment, and a park; and Lorain, Ohio—in a SOHIO gas station store, and a hospital room. -

Scholarship & Award Breakfast

15TH ANNUAL Scholarship & Award Breakfast Tuesday, April 10, 2012 Dear friends, Good morning! Sherry and I are thrilled to welcome you to the 15th annual Scholarship and Award Breakfast. This is one of our favorite events — what a delight to see our students come together with our scholarship donors and supporters, you who help our students make their plans and dreams come true. At last year’s breakfast, Nelson Carpluk ’12 spoke of the impact scholarship funds had on his ability to complete his schooling. He talked about the motivation he derived from regular communication with his scholarship donors. And he talked about his plans for the future. The University of Alaska Fairbanks is in the business of helping develop a strong Alaska workforce; build intellectual strength; and make a place in this busy world for quiet inquiry. This is heady stuff, and none of it could happen without students’ hard work and donor support. Thank you for all you do to make it possible. Enjoy the morning. Sincerely, Chancellor Brian Rogers Program Cover Artwork: “Blueberries” Klara Maisch Art | 2011 – 2012 Bebe Helen Kneece Woodward Scholarship Program BREAKFAST IS SERVED! Emcee Jeri Wigdahl Community volunteer MUSICAL PERFORMANCE Trevor Adams, viola Music major | 2011 – 2012 String Players Fund Kailyn Davis, clarinet Music major | 2011 – 2012 Pearl Berry Boyd Music Scholarship | 2011 – 2012 Patricia Hughes Eastaugh Teaching Scholarship Ellen Parker, clarinet Music major | 2011 – 2012 Pep Band Support INSPIRING STUDENT SUCCESS Brian Rogers Chancellor, University of Alaska Fairbanks A LONG WAY FROM HOME Theresia Schnurr Biochemistry major | 2011 – 2012 Cynthia J. Northrup Physical Education Scholarship GETTING THE WORD OUT, CONNECTING WITH PEOPLE Wynola Possenti ’68, ’75 UAF donor | Richard G. -

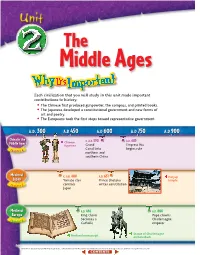

Chapter 4: China in the Middle Ages

The Middle Ages Each civilization that you will study in this unit made important contributions to history. • The Chinese first produced gunpowder, the compass, and printed books. • The Japanese developed a constitutional government and new forms of art and poetry. • The Europeans took the first steps toward representative government. A..D.. 300300 A..D 450 A..D 600 A..D 750 A..DD 900 China in the c. A.D. 590 A.D.683 Middle Ages Chinese Middle Ages figurines Grand Empress Wu Canal links begins rule Ch 4 apter northern and southern China Medieval c. A.D. 400 A.D.631 Horyuji JapanJapan Yamato clan Prince Shotoku temple Chapter 5 controls writes constitution Japan Medieval A.D. 496 A.D. 800 Europe King Clovis Pope crowns becomes a Charlemagne Ch 6 apter Catholic emperor Statue of Charlemagne Medieval manuscript on horseback 244 (tl)The British Museum/Topham-HIP/The Image Works, (c)Angelo Hornak/CORBIS, (bl)Ronald Sheridan/Ancient Art & Architecture Collection, (br)Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY 0 60E 120E 180E tecture Collection, (bl)Ron tecture Chapter Chapter 6 Chapter 60N 6 4 5 0 1,000 mi. 0 1,000 km Mercator projection EUROPE Caspian Sea ASIA Black Sea e H T g N i an g Hu JAPAN r i Eu s Ind p R Persian u h . s CHINA r R WE a t Gulf . e PACIFIC s ng R ha Jiang . C OCEAN S le i South N Arabian Bay of China Red Sea Bengal Sea Sea EQUATOR 0 Chapter 4 ATLANTIC Chapter 5 OCEAN INDIAN Chapter 6 OCEAN Dahlquist/SuperStock, (br)akg-images (tl)Aldona Sabalis/Photo Researchers, (tc)National Museum of Taipei, (tr)Werner Forman/Art Resource, NY, (c)Ancient Art & Archi NY, Forman/Art Resource, (tr)Werner (tc)National Museum of Taipei, (tl)Aldona Sabalis/Photo Researchers, A..D 1050 A..D 1200 A..D 1350 A..D 1500 c. -

20 Sunderlands Links to Slavery

LOCAL STUDIES CENTRE FACT SHEET NUMBER 20 Sunderland’s links to slavery The Hilton family were an important family in the North JAMES FIELD STANFIELD (1749 – 1824) East and owned Hilton Castle in Sunderland, the name Actor, author and campaigner against the Slave Trade changed to Hylton by the 19th century. lived in a house on this site, which was also the birthplace of his son CLARKSON STANFIELD R.A (1793 – 1867) The Hylton’s were a sea faring family who forged links with Theatre, marine and landscape painter the Caribbean. Sir William Hylton was a mariner and salt merchant who went to America in 1621 and settled in There was popular support in Sunderland for an end to New Hampshire. Anthony Hylton from South Shields slavery as shown in the 1790s by petitions and the fact that (probably a relative of Sir William) took settlers to the town’s grocers had agreed to cease selling sugar Jamestown, Virginia in 1623. It is probable that William and produced in the slave plantations of the West Indies. Anthony were connected to the Hyltons at Hylton Castle. Campaigning continued after the abolition of the British Descendants of William Hylton settled in Maryland, Carolina slave trade in 1808 and slavery in the British Empire in and Jamaica before 1700. Records show that Ralph Hilton 1838. Frederick Douglas, the fugitive enslaved worker and of South Shields went to Jamaica in the 1740s and owned antislavery campaigner addressed a meeting in Sunderland slave plantations there. Like many of the first settlers, in 1846. The Dominican Celestine Edwards (1858 – 1894) involvement in the slave trade and slavery grew out of briefly lived in Sunderland before moving to London. -

1 This Was the Year That the Shadows Appeared As Singers Before a Pan

1975 This was the year that The Shadows appeared as singers before a pan-European audience. The earlier 1973 initiative had not produced the desired outcome and by 1974 they were in the wilderness and did not exist as a viable group. They got together to perform at the Palladium on 27 October of that year as a personal tribute to and for the benefit of the widow of BBC producer Colin Charman. BBC boss Bill Cotton heard them and suggested that they might like to represent the UK at the Eurovision Song Contest the following year. They accepted, formed a working ensemble, and undertook a few local ‘practice’ gigs while preparing and practising the songs. The chosen song, [254] LET ME BE THE ONE, was one of six put forward for the UK’s entry in the Eurovision Contest of 1975, and was the last of the contenders performed over six successive weeks on Lulu’s BBC TV show at the start of the year. It was duly televised in Stockholm on 22 March but came in second to Dutch group Teach-In’s lyrically challenged ‘Dinge-Dong’ ~ English title ‘Ding-A-Dong’ (“Ding- A-Dong every hour,/ When you pick a flower …”), which impressed the British public sufficiently to enjoy a seven-week residence in the Singles charts (climbing to No.13). No such good fortune attended the release of The Shadows’ follow-up to their charting Eurovision Single, another piece from the same composer, the staggeringly inane, hopelessly unamusing [266] RUN BILLY RUN (“Closed my eyes, I tried countin’ sheep,/ Desp-rate Dan just looked like Bo-Peep,/ I can’t sleep”). -

Dorothy Potter and the Wizards of Oz

Dorothy Potter And The Wizards Of Oz Script and Lyrics by: Janinne Chadwick c. 2016 For Little People’s Repertory Theatre Script and Lyrics by: Janinne Chadwick c. 2016 Act One: Scene 1 A Nursery Lullaby A nursery that includes a crib and a shelf or dresser. Baby Dorothy is standing in her crib. Her mother is rocking in a rocking chair, knitting. Her father is off-stage. Baby Dorothy: (calling for her father) Daddy! Daddy! Bertie Beans! Lillian: No more candy, darling, it’s time for bed. Father enters. Jim: Did I hear my favorite little witch calling for me? Lillian: Say goodnight to Daddy and I’ll sing you a lullaby. Baby Dorothy: Goodnight Daddy. Lullaby Lillian: Rock a bye, Dorothy, in your baby bed One day you’ll fly on a broomstick instead When the owl comes calling you’ll study and play And learn to use magic in a school far away Veldamort enters. She has a Ruby wand. She points her wand at Father and he falls down dramatically as Mother tries to shield Dorothy. Lillian: (screams) No, not Dorothy! Curse me instead. Veldamort: Out of my way, silly woman! Veldamort waves her wand at Mother, who falls to the ground. Veldamort: (to Dorothy) And now my pretty! There’s not room in this world for the both of us! Avada Kedavra! The spell deflects onto Veldamort, who writhes in pain and staggers out of the room. Veldamort: (as she’s leaving) Ahhh, what have you done? Baby Dorothy: (reaches for her forehead where her ruby scar has appeared) Owie! Mama, Owie. -

082 out of the Shadows Text 9/12/03 9:36 AM Page 1

082 Out of the Shadows Cover 1/20/04 10:14 AM Page 1 If someone you love has an addiction, you may be exhausted by years of trying unsuccessfully to save him or her from self-defeating choices. This book can show you how to make changes that can free you for a life of joy and peace. Learn how to stop feeling responsible for your loved one’s choices. Learn how you can help—and how you need to let go. Letting go may even bring about the healing you’ve been hoping for. Lutheran Hour M inistries ® Lutheran Hour M inistries Lutheran Hour Ministries Lutheran Hour ® M inistries 6BE81 Lutheran Hour M inistries ® Lutheran Hour M inistries Lutheran Hour M inistries Lutheran Hour Ministries 082 Out of the Shadows Text 9/12/03 9:36 AM Page 1 Out of the Shadows When Someone You Love Has an Addiction by Sam N. Foster, LCSW 082 Out of the Shadows Text 9/12/03 9:36 AM Page 2 Lutheran Hour ® Ministries © 2001 Int’l LLL The Int’l Lutheran Laymen’s League, with its outreach through Lutheran Hour Ministries, is an auxiliary of The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod and Lutheran Church—Canada. Scripture taken from the HOLY BIBLE; NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®, NIV®, Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan Publishing House. Capitalization of pronouns referring to the Deity has been added and is not part of the original New International Version text. 082 Out of the Shadows Text 9/12/03 9:36 AM Page 3 Wanting to Help Often those living with or caring deeply about someone who has an addiction recognize there is a serious problem long before the addict does. -

College for All? Is There Too Much Emphasis on Getting a 4-Year College Degree? Research Synthesis

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 431 986 CG 029 345 AUTHOR Boesel, David; Fredland, Eric TITLE College for All? Is There Too Much Emphasis on Getting a 4-Year College Degree? Research Synthesis. INSTITUTION Wisconsin Univ., Madison. Medical Center. SPONS AGENCY National Library of Education (ED/OERI), Washington, DC. REPORT NO NLE-1999-2024 PUB DATE 1999-01-00 NOTE 96p. PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070) Numerical/Quantitative Data (110) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Academic Ability; *Bachelors Degrees; *College Graduates; Community Colleges; Debt (Financial); Dropouts; Higher Education; *Labor Market; *Research; Salaries; School Holding Power; Tables (Data); Vocational Education ABSTRACT Over the years, larger and larger portions of high school graduates have enrolled in 4-year colleges. Although many people view college as essential to success in the labor market, the movement toward 4-year colleges also has its critics. These critics contend that the public has come to believe that almost all high school graduates should go to college. This "college movement" is sweeping many marginally qualified or unqualified students into college, and hence the average ability of college students has declined. As a result of these declining ability levels, college noncompletion and dropout rates have increased. Many noncompleters do poorly in the labor market and would have been better advised to pursue other education and training options. These noncompleters are also burdened by unnecessary debts from college loans. Even college graduates are not doing very well in the labor market. This research synthesis examines the evidence for these arguments. Based on published literature identified through traditional bibliographic sources, ERIC, a variety of internet sources, research reports, and Ph.D.