R.N.D. Royal Naval Division

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COMPTE-RENDU DE LA RÉUNION DU CONSEIL MUNICIPAL Du 2 Avril 2019

COMPTE-RENDU DE LA RÉUNION DU CONSEIL MUNICIPAL du 2 Avril 2019 L’an 2019, le 2 Avril à 19 heures, le Conseil Municipal de la Commune de Maroeuil s’est réuni à la mairie, lieu ordinaire de ses séances, sous la présidence de Monsieur DAMART Daniel, Maire, en session ordinaire. Les convocations individuelles, contenant l’ordre du jour, ont été transmises par écrit aux conseillers municipaux le 27/03/2019. La convocation et l’ordre du jour ont été affichés à la porte de la Mairie le 28/03/2019. Présents : M. DAMART Daniel, Maire, Mmes : DUPENT Marie-Andrée, HARLE Florence, LAGACHE Armel, LOURDE-ROCHEBLAVE Alexandra, SERLET Véronique, Melle JOLIBOIS Karine, MM : CARBONNET Thomas, DEBOVE Marcel, DEMAREST Marc, DUEZ François-Xavier, FRANCOIS Serge, PUCHOIS Michel, VANIET Vincent Procuration(s): Mmes : CUISINIER Anne-Sylvie à M. DAMART Daniel, RAMS Dominique à Mme HARLE Florence, MM : DESAILLY Frédéric à Mme DUPENT Marie-Andrée, DOUDAIN Jean-Luc à M. FRANCOIS Serge Excusé(s) : Mme LEMAIRE Nathalie A été nommé(e) secrétaire : Mme LOURDE-ROCHEBLAVE Alexandra Monsieur le Maire ouvre la séance du Conseil Municipal en demandant aux personnes présentes d’observer une minute de silence en hommage de Monsieur Jean-Jacques PAYEN, agent communal décédé le 29 mars 2019. 2019DE9 : Subvention à l'association "A.I.M.E" CONSIDÉRANT le contexte budgétaire particulièrement contraint pour les collectivités territoriales, CONSIDÉRANT la volonté de la municipalité de ne pas répercuter sur les associations les baisses de recettes liées à la baisse des dotations de l'Etat, CONSIDÉRANT la proposition du bureau municipal de maintenir en 2019, sauf demande inférieure de l'association, le niveau des subventions attribuées aux associations en 2018, hors subventions exceptionnelles, CONSIDÉRANT la demande de subvention déposée par l'association, Le Conseil Municipal, après en avoir délibéré, DÉCIDE d’attribuer une subvention de 800 € à l’association "A.I.M.E" au titre de l’année 2019. -

The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2Nd December 1917

Centre for First World War Studies A Moonlight Massacre: The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2nd December 1917 by Michael Stephen LoCicero Thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts & Law June 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The Third Battle of Ypres was officially terminated by Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig with the opening of the Battle of Cambrai on 20 November 1917. Nevertheless, a comparatively unknown set-piece attack – the only large-scale night operation carried out on the Flanders front during the campaign – was launched twelve days later on 2 December. This thesis, a necessary corrective to published campaign narratives of what has become popularly known as „Passchendaele‟, examines the course of events from the mid-November decision to sanction further offensive activity in the vicinity of Passchendaele village to the barren operational outcome that forced British GHQ to halt the attack within ten hours of Zero. A litany of unfortunate decisions and circumstances contributed to the profitless result. -

Inventaire Des Cavités Souterraines Achicourt – Arras – Beaurains

Inventaire des cavités souterraines Achicourt – Arras – Beaurains Réunion de concertation du 24 avril 2018 Déroulement Contexte Objectifs Présentation des résultats d’étude (Alp’géorisques) Débat Inventaire des cavités souterraines Achicourt – Arras – Beaurains Réunion de concertation du 24 avril 2018 Contexte général Les cavités souterraines : une réalité Des cavités connues et valorisées ; Des mouvements de terrains recensés ; Des nouvelles carrières découvertes impactant des projets de rénovation urbaine. Source : https://www.carrierewellington.com/ Inventaire des cavités souterraines Achicourt – Arras – Beaurains Réunion de concertation du 24 avril 2018 Source : Rapport d’étude SEMOFI Contexte : Les impacts => Impacts sur le bâti : - Fissures ; - Tassements ; - effondrement. => Impacts sur les réseaux : - Fuites de réseaux ; - Canalisations rompus. => Impacts économiques : - Relogement ; - Arrêt d’activités. => Impacts sur les personnes : - Foyers privés d’électricité, gaz, eau ; - Mise en place de déviation ; - Danger pour les vies humaines Inventaire des cavités souterrainesSource : Achicourt DDTM – Arras 62 – Beaurains Réunion de concertation du 24 avril 2018 Objectifs => Sensibiliser et accompagner ; => Améliorer la prise en compte du risque dans l’aménagement du territoire ; => Proposer un programme d’étude ou de surveillance des cavités recensées avérées. Diagnostic : S’assurer de l’état et la stabilité de la carrière ; Intervenir au plus tôt pour limiter les coûts ; Pérenniser la connaissance. Inventaire des cavités souterraines Achicourt – Arras – Beaurains Réunion de concertation du 24 avril 2018 Étude du risques de mouvements de terrain liés aux cavités souterraines sur le territoire de la communauté urbaine d’Arras. Direction Départementale des Territoires Communes d’Arras, Beaurains et et de la Mer du Pas-de-Calais Achicourt (Tranche Ferme) Préfet du Pas-de-Calais COCON – 24 avril 2018 Ordre du jour Rappel du contexte ; Type de cavités identifiées ; Travaux réalisés ; Restitution des travaux ; Échanges. -

Canada and the BATTLE of VIMY RIDGE 9-12 April 1917 Bataille De Vimy-E.Qxp 1/2/07 11:37 AM Page 4

BRERETON GREENHOUS STEPHEN J. HARRIS JEAN MARTIN Bataille de Vimy-E.qxp 1/2/07 11:37 AM Page 2 Bataille de Vimy-E.qxp 1/2/07 11:37 AM Page 1 Bataille de Vimy-E.qxp 1/2/07 11:37 AM Page 3 BRERETON GREENHOUS STEPHEN J. HARRIS JEAN MARTIN Canada and the BATTLE OF VIMY RIDGE 9-12 April 1917 Bataille de Vimy-E.qxp 1/2/07 11:37 AM Page 4 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Greenhous, Brereton, 1929- Stephen J. Harris, 1948- Canada and the Battle of Vimy Ridge, 9-12 April 1917 Issued also in French under title: Le Canada et la Bataille de Vimy 9-12 avril 1917. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-660-16883-9 DSS cat. no. D2-90/1992E-1 2nd ed. 2007 1.Vimy Ridge, Battle of, 1917. 2.World War, 1914-1918 — Campaigns — France. 3. Canada. Canadian Army — History — World War, 1914-1918. 4.World War, 1914-1918 — Canada. I. Harris, Stephen John. II. Canada. Dept. of National Defence. Directorate of History. III. Title. IV.Title: Canada and the Battle of Vimy Ridge, 9-12 April 1917. D545.V5G73 1997 940.4’31 C97-980068-4 Cet ouvrage a été publié simultanément en français sous le titre de : Le Canada et la Bataille de Vimy, 9-12 avril 1917 ISBN 0-660-93654-2 Project Coordinator: Serge Bernier Reproduced by Directorate of History and Heritage, National Defence Headquarters Jacket: Drawing by Stéphane Geoffrion from a painting by Kenneth Forbes, 1892-1980 Canadian Artillery in Action Original Design and Production Art Global 384 Laurier Ave.West Montréal, Québec Canada H2V 2K7 Printed and bound in Canada All rights reserved. -

The Evolution of British Tactical and Operational Tank Doctrine and Training in the First World War

The evolution of British tactical and operational tank doctrine and training in the First World War PHILIP RICHARD VENTHAM TD BA (Hons.) MA. Thesis submitted for the award of the degree of Master of Philosophy by the University of Wolverhampton October 2016 ©Copyright P R Ventham 1 ABSTRACT Tanks were first used in action in September 1916. There had been no previous combat experience on which to base tactical and operational doctrine for the employment of this novel weapon of war. Training of crews and commanders was hampered by lack of vehicles and weapons. Time was short in which to train novice crews. Training facilities were limited. Despite mechanical limitations of the early machines and their vulnerability to adverse ground conditions, the tanks achieved moderate success in their initial actions. Advocates of the tanks, such as Fuller and Elles, worked hard to convince the sceptical of the value of the tank. Two years later, tanks had gained the support of most senior commanders. Doctrine, based on practical combat experience, had evolved both within the Tank Corps and at GHQ and higher command. Despite dramatic improvements in the design, functionality and reliability of the later marks of heavy and medium tanks, they still remained slow and vulnerable to ground conditions and enemy counter-measures. Competing demands for materiel meant there were never enough tanks to replace casualties and meet the demands of formation commanders. This thesis will argue that the somewhat patchy performance of the armoured vehicles in the final months of the war was less a product of poor doctrinal guidance and inadequate training than of an insufficiency of tanks and the difficulties of providing enough tanks in the right locations at the right time to meet the requirements of the manoeuvre battles of the ‘Hundred Days’. -

The German Army, Vimy Ridge and the Elastic Defence in Depth in 1917

Journal of Military and Strategic VOLUME 18, ISSUE 2 Studies “Lessons learned” in WWI: The German Army, Vimy Ridge and the Elastic Defence in Depth in 1917 Christian Stachelbeck The Battle of Arras in the spring of 1917 marked the beginning of the major allied offensives on the western front. The attack by the British 1st Army (Horne) and 3rd Army (Allenby) was intended to divert attention from the French main offensive under General Robert Nivelle at the Chemin des Dames (Nivelle Offensive). 1 The French commander-in-chief wanted to force the decisive breakthrough in the west. Between 9 and 12 April, the British had succeeded in penetrating the front across a width of 18 kilometres and advancing around six kilometres, while the Canadian corps (Byng), deployed for the first time in closed formation, seized the ridge near Vimy, which had been fiercely contested since late 1914.2 The success was paid for with the bloody loss of 1 On the German side, the battles at Arras between 2 April and 20 May 1917 were officially referred to as Schlacht bei Arras (Battle of Arras). In Canada, the term Battle of Vimy Ridge is commonly used for the initial phase of the battle. The seizure of Vimy ridge was a central objective of the offensive and was intended to secure the protection of the northern flank of the 3rd Army. 2 For detailed information on this, see: Jack Sheldon, The German Army on Vimy Ridge 1914-1917 (Barnsley: Pen&Sword Military, 2008), p. 8. Sheldon's book, however, is basically a largely indiscriminate succession of extensive quotes from regimental histories, diaries and force files from the Bavarian War Archive (Kriegsarchiv) in Munich. -

The Birth of Airpower, 1916 the Character of the German Offensive

The Birth of Airpower, 1916 359 the character of the German offensive became clear, and losses reached staggering levels, Joffre urgently demanded as early a start as possible to the allied offensive. In May he and Haig agreed to mount an assault on I July 'athwart the Somme.' Long before the starting date of the offensive had been fixed the British had been preparing for it by building up, behind their lines, the communications and logistical support the 'big push' demanded. Masses of materiel were accumulated close to the trenches, including nearly three million rounds of artillery ammuni tion. War on this scale was a major industrial undertaking.• Military aviation, of necessity, made a proportionate leap as well. The RFC had to expand to meet the demands of the new mass armies, and during the first six months of 1916 Trenchard, with Haig's strong support, strove to create an air weapon that could meet the challenge of the offensive. Beginning in January the RFC had been reorganized into brigades, one to each army, a process completed on 1 April when IV Brigade was formed to support the Fourth Army. Each brigade consisted of a headquarters, an aircraft park, a balloon wing, an army wing of two to four squadrons, and a corps wing of three to five squadrons (one squadron for each corps). At RFC Headquarters there was an additional wing to provide reconnais sance for GHQ, and, as time went on, to carry out additional fighting and bombing duties.3 Artillery observation was now the chief function of the RFC , with subsidiary efforts concentrated on close reconnaissance and photography. -

Memoire Technique Justificatif

RRééssuumméé nnoonn tteecchhnniiqquuee Recyclage des boues par épandage agricole Communauté Urbaine d’Arras Station d’épuration d’ARRAS (62) SVI/KTO/002016 - Septembre 2016 RRééssuumméé nnoonn tteecchhnniiqquuee ddee ll’’ééttuuddee dd’’iimmppaacctt La Communauté Urbaine d’Arras traite ses effluents au sein de stations d’épuration. Ce présent dossier concerne l’épandage des boues de la station d’épuration de la Communauté Urbaine d’Arras implantée sur la commune de Saint Laurent Blangy. Cet ouvrage a une capacité de traitement de 140 000 équivalents-habitants par aération prolongée à faible charge avec un traitement spécifique de l’azote et du phosphore. Les boues sont épandues dans les départements du Nord et du Pas-de-Calais. Les boues issues de cet ouvrage sont conditionnées au chlorure ferrique et à la chaux puis déshydratées par filtre-presse. Les boues sont ensuite orientées vers une aire de stockage permettant d’entreposer les boues avant leur épandage en agriculture. L'étude est basée sur un fonctionnement à long terme tenant compte des prévisions de raccordements au réseau d’assainissement ainsi que le traitement des boues des stations d’épuration de Bailleul Sir Berthoult, Wailly les Arras, Fampoux, Feuchy/Athies, Thélus, Gavrelle et Mercatel sur la station d’épuration de Saint Laurent Blangy. La production prévue est de 15 600 tonnes de brutes de boues déshydratées et chaulées. L’azote, le phosphore, la magnésie et le calcium constituent l’intérêt majeur de ces boues. La valeur fertilisante des boues est présentée dans le tableau -

Victory, 1918' at the Canadian War Museum

Canadian Military History Volume 28 Issue 1 Article 25 2019 Constructing and Deconstructing 'Victory, 1918' at the Canadian War Museum Tim Cook Marie-Louise Deruaz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Cook, Tim and Deruaz, Marie-Louise "Constructing and Deconstructing 'Victory, 1918' at the Canadian War Museum." Canadian Military History 28, 1 (2019) This Canadian War Museum is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cook and Deruaz: Constructing and Deconstructing 'Victory, 1918' CANADIAN WAR MUSEUM Constructing and Deconstructing Victory, 1918 at the Canadian War Museum TIM COOK & MARIE-LOUISE DERUAZ Abstract : This article explores the history behind the creation of the Canadian War Museum’s exhibition, Victory, 1918: The Last Hundred Days. The exhibition presented the story of the Canadian Corps during the Hundred Days campaign of the First World War and the Canadian contributions to Allied victory. What follows is a glimpse into the challenges of exhibition development. Together, artifacts, personal stories, films, works of art, immersive spaces, reconstructions and colourized historical photographs created an engaging visitor experience while communicating key concepts about the Hundred Days. Cet article explore l’histoire de la création de l’exposition Victoire 1918: Les cent derniers jours du Musée canadien de la guerre. L’exposition présentait l’histoire du Corps canadien lors de la campagne des Cent Jours de la Première Guerre mondiale et les contributions canadiennes à la victoire des Alliés. -

Monchy-Le-Preux

COMMUNAUTE URBAINE D’ARRAS COMMUNE DE MONCHY-LE-PREUX PLAN LOCAL D’URBANISME RAPPORT DE PRESENTATION 1 Approuvé par délibération du Conseil Communautaire du : 17 novembre 2006 COMMUNAUTE URBAINE D’ARRAS COMMUNE DE MONCHY-LE-PREUX – PAS-DE-CALAIS 2 PLAN LOCAL D’URBANISME – RAPPORT DE PRESENTATION SOMMAIRE INTRODUCTION 4 Présentation de la commune 5 1 - DIAGNOSTIC PROSPECTIF ET BESOINS REPERTORIES 8 1.01 - Le Schéma Directeur de l’Arrageois 9 1.02 - Démographie 12 1.03 - Habitat 20 1.04 - Activités Economiques 30 1.05 - Besoins en surfaces urbanisables 43 1.06 - Circulation et déplacements 44 1.07 - Equipements et services 49 1.08 - Protection de l’environnement 53 2- ETAT INITIAL DE L’ENVIRONNEMENT 56 2.01 - Le site et le milieu naturel 57 2.02 - Les paysages et l’environnement 61 2.03 - Les éléments d’histoire locale et le patrimoine 65 2.04 - La structure du bâti 70 2.05 - Les risques 73 2.06 - Données environnementales 76 COMMUNAUTE URBAINE D’ARRAS COMMUNE DE MONCHY-LE-PREUX – PAS-DE-CALAIS 3 PLAN LOCAL D’URBANISME – RAPPORT DE PRESENTATION 3 – JUSTIFICATION DES DISPOSITIONS DU P.L.U. 80 3.01 - Les objectifs de l’élaboration du P.L.U. de Monchy-le-Preux 81 3.02 - Le zonage du P.L.U. et la vocation des zones 84 3.03 - La réglementation du P.L.U. 90 3.04 - La réponse aux objectifs de développement Durable 104 3.05 - Les documents d’urbanisme supracommunaux 109 3.06 - Cohérence avec les documents d’urbanisme des communes contiguës 111 4 - LES INCIDENCES DU P.L.U. -

Fallen 1914 - 1918

THE FALLEN 1914 - 1918 part two shenington THE FALLEN 1914-1918 About “The Fallen” – Part Two The author of The Fallen, a tribute to the men from Alkerton and Shenington who fell in the two world wars, is Alistair Cook of Tysoe Hill Cottage in Shenington. When former Shenington Green editor Carole Young appealed for information on the six men named on the Alkerton war memorial, Alistair, a confirmed ‘non-historian,’ decided to pursue a fascination cultivated over long dog walks: namely, the lost stories behind the many names engraved on the large chunks of stone that take pride of place in our local villages. The Fallen, Part Two follows the publishing of Part One in the December 2015 issue of the Shenington Green. Part one covered the stories of the men remembered on the Alkerton war memorial; part two honours the men whose names are listed on a plaque in Shenington church and Richard Coles, a young Shenington soldier whose name is honoured on a small wooden plaque hanging just below it. The Fallen was inspired by the stories of Epwell’s soldiers killed in the wars, compiled by local historian Eric Kaye, who also wrote the story of the Edgehill airfield. Alistair spent weeks finding the soldiers’ respective regimental details, where they are buried, what they had done, where they lived and the actions that took place on or around the dates they fell. This was all achieved with the help of the internet and a visit to the National Archives in Kew where Alistair was allowed access to all records, free of charge. -

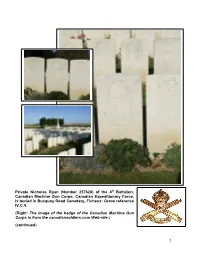

Ryan, Nicholas

Private Nicholas Ryan (Number 257628) of the 4th Battalion, Canadian Machine Gun Corps, Canadian Expeditionary Force, is buried in Bucquoy Road Cemetery, Ficheux: Grave reference IV.C.9. (Right: The image of the badge of the Canadian Machine Gun Corps is from the canadiansoldiers.com Web-site.) (continued) 1 His occupation prior to military service recorded as that of a farm labourer, Nicholas Ryan appears to have left behind him no history of his movement from the Dominion of Newfoundland to Canada. There is a Nicholas Ryan found on the passenger list of the SS Ivermore for the journey of May 28, 1912, from Port aux Basques to North Sydney, Nova Scotia, the young man on his way to the industrial city of Sydney, but this is hardly enough to confirm him as the subject of this biography. All that may said with any certainty is that he was a resident of the province of Saskatchewan – his only given address at the time – in October of 1917, for that was where and when he was called up by means of the Canadian Military Service Act of 1917 – otherwise known as conscription. It was in the small community of Melville that Nicholas Ryan (Military Service Number 453333*) underwent a medical examination on October 16, 1917, which found him as…fit for dispatching overseas. The number 2 in his given category, A2, indicates that he had undergone no prior training. *Not to be confused with his designated Regimental Number, 257628. It was to be some thirteen weeks later, on January 18, that he was called up and attested in the provincial capital city, Regina, and taken on strength by the 1st Depot Battalion* of the Saskatchewan Regiment.