Proper Display of Bidirectional Structured Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Standard Iso/Iec 10646

This is a preview - click here to buy the full publication INTERNATIONAL ISO/IEC STANDARD 10646 Sixth edition 2020-12 Information technology — Universal coded character set (UCS) Technologies de l'information — Jeu universel de caractères codés (JUC) Reference number ISO/IEC 10646:2020(E) © ISO/IEC 2020 This is a preview - click here to buy the full publication ISO/IEC 10646:2020 (E) CONTENTS 1 Scope ..................................................................................................................................................1 2 Normative references .........................................................................................................................1 3 Terms and definitions .........................................................................................................................2 4 Conformance ......................................................................................................................................8 4.1 General ....................................................................................................................................8 4.2 Conformance of information interchange .................................................................................8 4.3 Conformance of devices............................................................................................................8 5 Electronic data attachments ...............................................................................................................9 6 General structure -

Unicode and Code Page Support

Natural for Mainframes Unicode and Code Page Support Version 4.2.6 for Mainframes October 2009 This document applies to Natural Version 4.2.6 for Mainframes and to all subsequent releases. Specifications contained herein are subject to change and these changes will be reported in subsequent release notes or new editions. Copyright © Software AG 1979-2009. All rights reserved. The name Software AG, webMethods and all Software AG product names are either trademarks or registered trademarks of Software AG and/or Software AG USA, Inc. Other company and product names mentioned herein may be trademarks of their respective owners. Table of Contents 1 Unicode and Code Page Support .................................................................................... 1 2 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 3 About Code Pages and Unicode ................................................................................ 4 About Unicode and Code Page Support in Natural .................................................. 5 ICU on Mainframe Platforms ..................................................................................... 6 3 Unicode and Code Page Support in the Natural Programming Language .................... 7 Natural Data Format U for Unicode-Based Data ....................................................... 8 Statements .................................................................................................................. 9 Logical -

Character Properties 4

The Unicode® Standard Version 14.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see https://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2021 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at https://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see https://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 14.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-29-0 (https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/) 1. -

Tech Day: Universal Acceptance

Tech Day: Universal Acceptance Mark Švančárek Universal Acceptance Today’s Objectives • Definition of Universal Acceptance • Universal Acceptance Steering Group • Challenges • BiDi Stuff • Conclusion 2 Definition of Universal Acceptance ALL domain names and ALL email addresses should work in ALL Internet-enabled applications, devices and systems 3 Universal Acceptance Steering Group (UASG) • A community-based team • ICANN's role is that of supporter, provider of funds • Formed to identify topline issues and proposed solutions, and disseminate best practices • Objective: Help software developers and website owners update systems to keep pace with evolving Internet standards • Message: Universal Acceptance will enable the next billion users build and access their own spaces and identities online • UASG.tech 4 UASG Activities Review Popular Websites, Dev Frameworks, Browsers, OS Build Use Cases, Test Environments, EAI Community Outreach Live Workshops, Panel Discussions, Presentations Writing Knowledge Databases, Whitepapers, Quick Guides 5 Challenges • Technical Challenges • Challenging old assumptions Today’s • Updating old software discussion • Managing backward-compatibility • Business Challenges Learn more • Understanding the opportunity at UASG.tech • Evaluating return on investment 6 Technical Challenges – Old Assumptions • Sometimes coders make bad assumptions about domain name strings and email address strings • This may be because RFCs have changed (e.g. SMTPUTF8) • Or standards may be misleading (e.g. HTML5.3 email input type definition) -

Middle East-I 9 Modern and Liturgical Scripts

The Unicode® Standard Version 13.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2020 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 13.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-26-9 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode13.0.0/) 1. -

Introduction to Universal Acceptance (UA)

Introduction to Universal Acceptance (UA) Universal Acceptance Steering Group (UASG) 23 September 2019 Universal Acceptance – Report UASG007 TABLE OF CONTENTS About This Document 4 Target Audience 4 Background Concepts 5 Domain Names 5 Country Code Top-level Domains (ccTLDs) 5 Generic Top-level Domains (gTLDs) 5 Domain Name Internationalization 6 The Need for Universal Acceptance (UA) 6 U-labels and A-labels 6 Email Address Internationalization (EAI) 7 Dynamic Link Generation (Linkification) 8 The Dynamic Nature of the Root Zone Registry 8 Universal Acceptance in Action 9 Five Criteria of Universal Acceptance 9 User Scenarios 11 Nonconformance to Universal Practices 12 Technical Requirements for UA Readiness 13 High-Level Requirements 13 Developer Considerations 14 Designing Software for Compatibility and Flexibility 14 Good Practices for Developing and Updating Software to Achieve UA-Readiness 14 Authoritative Sources for Domain Names: DNS Root Zone and IANA Lists 21 Email with IDNs and Why It Is Not the Same as EAI 21 Linkification and Its Challenges 22 Good Practice Recommendations 22 Unicode - Background and Code Point Attributes 23 UTF8, UTF16, and Other Encoding Methods 23 IDNA - A Brief History and Current State 24 Use Cases for Testing 24 Upgrading Software for EAI 25 Advanced Topics 25 Complex Scripts 25 Right-to-Left Languages and Unicode Conformance 25 The Bidi Algorithm 25 The Bidi Rule for Domain Names 27 Joiners 27 Homoglyphs and Similar Characters 28 Introduction to Universal Acceptance - Report UASG007 // 2 Normalization, Case Folding, and String Preparation 28 Case Folding and Mapping 30 Glossary and Other Resources 31 Glossary 31 RFCs and Key Standards 34 Key Standards 37 Online Resources 38 Introduction to Universal Acceptance - Report UASG007 // 3 About This Document The Internet’s technologies, including its naming components, continually evolve and change. -

Arabic Alphabet Pdf

Arabic alphabet pdf Continue It is used by many to start any language by teaching it parts of speech; however, it is logically better to start our trip by teaching arabic alphabet (Arabic letters), as this is a reasonable starting point. Consider the lack of alphabets, then, how can we form words and/or sentences?! Pronunciation Of Transliteered Isolated Isolated َ د d'l دَال kh ﺧـ ـﺨـ ـﺦ As Ch in the name of Bach خ khā̛ َﺧﺎء h ﺣـ ـﺤـ ـﺢ hā̛ in pronunciation َﺣﺎء j ﺟـ ـﺠـ ـﺞ Sometimes as G in a Girl or, as J's Jar ج Jim ﺛـ ـﺜـ ـﺚ ِﺟﻴﻢ As Th in the theory of ث thā̛ ﺛَﺎء t ت ﺗـ ـﺘـ ـﺖ ـﺔ tā̛ ﺗَﺎء Like T in Tree ت tā̛ ﺗَﺎء b ﺑـ ـﺒـ ـﺐ bā̛ - As B in Baby ـﺎ ـﺎ ﺑَﺎء leff as in Apple̛ أﻟِﻒ Pronunciation Original Medial Final Transcription ﺿـ ـﻀـ ـﺾ as D in the dead still heavy in pronunciation ض d'd َﺿﺎد with ﺻـ ـﺼـ ـﺺ As S in the garden is still heavy in pronunciation ص garden َﺻﺎد sh ﺷـ ـﺸـ ـﺶ as w in she ِﺷﻴﻦ ش shins ﺳـ ـﺴـ ـﺲ sin - Like S in see ِﺳﻴﻦ z ز ـﺰ ـﺰ As in the zoo ز z'y َزاي r ـﺮ ـﺮ rā̛ - Like R in Rama and َراء z ذ ـﺬ ـﺬ Like The Th's ذ z'l ذَال d د ـﺪ ـﺪ as D's dad َ َ How F ف fā̛ ﻓَﺎء gh ﻏـ ـﻐـ ـﻎ As Gh in Gandhi غ ghain ﻋـ ـﻌـ ـﻊ ̛ع ﻏَﻴﻦ /aliﻋﻠﻲ /ع has no real equivalent sometimes they replace it sound with sound like, for example, Ali's name for ع ainﻋَﻴ ٍﻦ ع ẓ ﻇـ ـﻈـ ـﻆ As in zorro still heavy in pronunciation ظ ẓā̛ ﻇﺎء tons ﻃـ ـﻄـ ـﻂ As T in the table is still heavy in pronunciation ط tā̛ ﻃﺎء d <ﺻـ ـﺼـ ـﺺ <7 w'w'w' , Like the W in response to the وَاو h ﻫـ ـﻬـ ـﻪ Like the H in He ه ﻫـ hā̛ ﻫَﺎء n ﻧـ ـﻨـ ـﻦ nun - Like the -

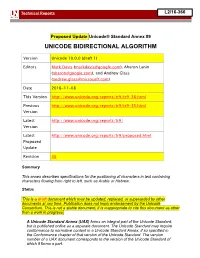

UAX #9: Unicode Bidirectional Algorithm

Technical Reports Proposed Update Unicode® Standard Annex #9 UNICODE BIDIRECTIONAL ALGORITHM Version Unicode 10.0.0 (draft 1) Editors Mark Davis ([email protected]), Aharon Lanin ([email protected]), and Andrew Glass ([email protected]) Date 2016-11-08 This Version http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr9/tr9-36.html Previous http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr9/tr9-35.html Version Latest http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr9/ Version Latest http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr9/proposed.html Proposed Update Revision 36 Summary This annex describes specifications for the positioning of characters in text containing characters flowing from right to left, such as Arabic or Hebrew. Status This is a draft document which may be updated, replaced, or superseded by other documents at any time. Publication does not imply endorsement by the Unicode Consortium. This is not a stable document; it is inappropriate to cite this document as other than a work in progress. A Unicode Standard Annex (UAX) forms an integral part of the Unicode Standard, but is published online as a separate document. The Unicode Standard may require conformance to normative content in a Unicode Standard Annex, if so specified in the Conformance chapter of that version of the Unicode Standard. The version number of a UAX document corresponds to the version of the Unicode Standard of which it forms a part. Please submit corrigenda and other comments with the online reporting form [Feedback]. Related information that is useful in understanding this annex is found in Unicode Standard Annex #41, “Common References for Unicode Standard Annexes.” For the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see [Unicode]. -

Displaying Bidirectional Text Concordances in KWIC Format

Displaying Bidirectional Text Concordances in KWIC format Pavel Rychl´y, Vojtˇech Kov´aˇr Faculty of Informatics Masaryk University Botanick´a68a, 602 00 Brno, Czech Republic {pary,xkovar3}@fi.muni.cz Abstract. The concordance view is one of the main functions of a corpus query system. Usually, it is displayed in the “Key Word(s) In Context” (KWIC) format. It is a table that contains a keyword (or keywords) in its middle column and the left and right context - words that girdle the keyword - in the other two columns. The concordance view enables corpus users to see all possible occurrences of the keyword easily. Other important task for corpus query system is to deal with as many languages as possible. Documents in corpora can also be bilingual or multilingual, e.g. many documents in any language contain English expressions. By handling languages with right-to-left script, e.g. Arabic or Persian, these bilingual documents are usually bidirectional. Since the data is stored in logical order, there is a problem how to display the correct word order in the concordance view. The current corpus query systems can not handle this task well. In the paper, we describe the problem of displaying bidirectional texts in the word concordance view and introduce a system that can handle these texts. A few examples of English word sequences in a corpus of Persian are given. We describe display algorithms and corpus input file modifications needed to achieve the correct word order in the concordance view. We also discuss some related problems, e.g. working with neutral characters (like punctuation or numbers) and the recognition of the left-to-right (right-to-left) text boundaries. -

The Unicode Standard, Version 3.0, Issued by the Unicode Consor- Tium and Published by Addison-Wesley

The Unicode Standard Version 3.0 The Unicode Consortium ADDISON–WESLEY An Imprint of Addison Wesley Longman, Inc. Reading, Massachusetts · Harlow, England · Menlo Park, California Berkeley, California · Don Mills, Ontario · Sydney Bonn · Amsterdam · Tokyo · Mexico City Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and Addison-Wesley was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial capital letters. However, not all words in initial capital letters are trademark designations. The authors and publisher have taken care in preparation of this book, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode®, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. If these files have been purchased on computer-readable media, the sole remedy for any claim will be exchange of defective media within ninety days of receipt. Dai Kan-Wa Jiten used as the source of reference Kanji codes was written by Tetsuji Morohashi and published by Taishukan Shoten. ISBN 0-201-61633-5 Copyright © 1991-2000 by Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or other- wise, without the prior written permission of the publisher or Unicode, Inc. -

Pdflib Tutorial 9.0.1

ABC PDFlib, PDFlib+PDI, PPS A library for generating PDF on the fly PDFlib 9.0.1 Tutorial For use with C, C++, Cobol, COM, Java, .NET, Objective-C, Perl, PHP, Python, REALbasic/Xojo, RPG, Ruby Copyright © 1997–2013 PDFlib GmbH and Thomas Merz. All rights reserved. PDFlib users are granted permission to reproduce printed or digital copies of this manual for internal use. PDFlib GmbH Franziska-Bilek-Weg 9, 80339 München, Germany www.pdflib.com phone +49 • 89 • 452 33 84-0 fax +49 • 89 • 452 33 84-99 If you have questions check the PDFlib mailing list and archive at tech.groups.yahoo.com/group/pdflib Licensing contact: [email protected] Support for commercial PDFlib licensees: [email protected] (please include your license number) This publication and the information herein is furnished as is, is subject to change without notice, and should not be construed as a commitment by PDFlib GmbH. PDFlib GmbH assumes no responsibility or lia- bility for any errors or inaccuracies, makes no warranty of any kind (express, implied or statutory) with re- spect to this publication, and expressly disclaims any and all warranties of merchantability, fitness for par- ticular purposes and noninfringement of third party rights. PDFlib and the PDFlib logo are registered trademarks of PDFlib GmbH. PDFlib licensees are granted the right to use the PDFlib name and logo in their product documentation. However, this is not required. Adobe, Acrobat, PostScript, and XMP are trademarks of Adobe Systems Inc. AIX, IBM, OS/390, WebSphere, iSeries, and zSeries are trademarks of International Business Machines Corporation. -

Consonant Characters and Inherent Vowels

HTML5: proposed markup Richard Ishida changes related to i18n W3C Internationalization Activity What I mean when I say HTML5 is… the main markup specification • http://dev.w3.org/html5/spec/ This presentation contains notes for most slides that can be accessed from the icon at the top left corner of the slide. Outline Character encoding Language Ruby Bidirectional text Date & time Character encoding Character encoding Encoding choice Other جعل شبكة الويب العالميّة عالميّة �حقا! وب �ﮫﺎ�ﯽ را ����ﯽ �ﮫﺎ�ﯽ ﺳﺎز�ﻢ! ﻋﺎﻟﻤﮕﻴﺮ ﻭﻳﺐ ﮐﻮ ﺣﻘﻴﻘﯽ ﻃﻮﺭ ﭘﺮ ﻋﺎﻟﻤﮕﻴﺮ ﺑﻨﺎﻧﺎ Համաշխարհային ցանցն իրոք համաշխարհային դարձնելը ASCII ᑖᑦᓱᒪ ᐃᑭᐊᖅᑭᕕᒃ ᓯᓚᕐᔪᐊᓕᒫᒥᒃ ᓈᕆᑎᑉᐹ. "Дүниежүзілік торды" нағыз дүниежүзілік етеміз! वल्ड वाई् वेबलाई यथाथ्ड म �व�वयााप बनाउने ! የዓለም አቀፉን ድር በእውነት አለም አቀፍ ማድረግ! UTF-8 Κάνοντας τον Παγκόσμιο Ιστό πραγματικά Παγκόσμιο ਵਰਡ ਵਾਈਡ ਵੈਬ ਨੂੰ ਵਾਕਈਵਿਵ-ਈਵਆਪੀ ਬਨਾਉਣਾ ! 缔造真正全球通行的万维网 ליצור מהרשת רשת כלל עולמית באמת! ˈmeɪkɪŋ ðə wɜːld waɪd wɛb ˈtruːlɪ ˈwɜːldˈwaɪd ワールド・ワイド・ウェッブを世界中に広げましょう េធ�ឲ្េេល វ េេវ៉បមានទូទវ ំងពិភទល ភពិ្ប! 전세계의 월드 와이드 웹으로 만들기! Gwneud y we fyd-eang yn wirioneddol fyd-eang! Unicode on the Web การทําให World Wide Web แพรหลายไปทั่วโลกอยางแทจริง འཛམ་ིང་ཡོངས་འེལ་འདི་ ངོ་མ་འབད་རང་ འཛམ་ིང་ཡོངས་�་བ་�གསཔ་བཟོ་བ། Character encoding Encoding declarations <!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Transitional//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-transitional.dtd"> <html lang='en' xml:lang='en' xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml"> <head> <meta http-equiv=Content-Type content="text/html; charset=utf-8" /> </head> ... • Strong encouragement to use UTF-8.