They're Gone a Decade, but Vince Lloyd's, Red Mottlow's Voices Remind of Eternal Friendships

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

W In, Lose, Or Draw Ji

Michigan Wins New Poll Over Notre Dame, 2 to 1 --- T.: ......;-i---1-1- Ballot Is 226 to 119 Yanks Sign Di Maggio Record Score Marks or Draw w in, Lose, At Believed Third Win By FRANCIS E. STANN In Special Vote of Figure Hogan's Dilemma in the Far West Nation's Writers Close to $70,000 At Los Angeles That curious hissing noise you may have been hearing in this fty Hm Aikoctotod Pr#kk ■y die Associated tr*u new year means, in all probability, that out on the West Coast those By Witt Grimsley NEW Jan. 6.—Joe Di LOS ANGELES, Jan. I.—Ben sponsors of the remarkable Rose Bowl pact between the Pacific Associated Press Sports Writer YORK, Mag- the gio of the Yankees announced today Hogan left town today, having ac- Conference and the Big Nine are rapidly approaching boiling NEW Jan. 6.—The burn- YORK, that he had signed a contract for complished the following feats In of the point. ing sport* question day— the coming season which made him the game of golf: The Coast Conference people who bought which was the greater college foot- "very happy,” and a consensus of Won the $10,000 Los Angeles Open have been ridiculed and ball of or this particular turkey power 1947, Michigan those who heard the great center- for the third time. Notre Dame—never to be settled on editorially tarred and feathered ever since they fielder express his pleasure placed Established a new the was answered today at record for the entered into an agreement which practically field, the amount of his stipend at close the ballot box—and it’s Michigan tournament at the Riviera Country handed over the Rose' Bowl to the Big Nine for to $70,000. -

Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: a Comparison of Rose V

Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 13 | Number 3 Article 6 1-1-1991 Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: A Comparison of Rose v. Giamatti and the 1921 Black Sox Trial Michael W. Klein Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_comm_ent_law_journal Part of the Communications Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael W. Klein, Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: A Comparison of Rose v. Giamatti and the 1921 Black Sox Trial, 13 Hastings Comm. & Ent. L.J. 551 (1991). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_comm_ent_law_journal/vol13/iss3/6 This Commentary is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: A Comparison of Rose v. Giamatti and the 1921 Black Sox Trial by MICHAEL W. KLEIN* Table of Contents I. Baseball in 1919 vs. Baseball in 1989: What a Difference 70 Y ears M ake .............................................. 555 A. The Economic Status of Major League Baseball ....... 555 B. "In Trusts We Trust": A Historical Look at the Legal Status of Major League Baseball ...................... 557 C. The Reserve Clause .......................... 560 D. The Office and Powers of the Commissioner .......... 561 II. "You Bet": U.S. Gambling Laws in 1919 and 1989 ........ 565 III. Black Sox and Gold's Gym: The 1919 World Series and the Allegations Against Pete Rose ............................ -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 116 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 116 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 165 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, DECEMBER 19, 2019 No. 206 Senate The Senate met at 9:30 a.m. and was U.S. SENATE, House amendment to the Senate called to order by the Honorable THOM PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE, amendment), to change the enactment TILLIS, a Senator from the State of Washington, DC, December 19, 2019. date. North Carolina. To the Senate: McConnell Amendment No. 1259 (to Under the provisions of rule I, paragraph 3, Amendment No. 1258), of a perfecting f of the Standing Rules of the Senate, I hereby appoint the Honorable THOM TILLIS, a Sen- nature. McConnell motion to refer the mes- PRAYER ator from the State of North Carolina, to perform the duties of the Chair. sage of the House on the bill to the The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- CHUCK GRASSLEY, Committee on Appropriations, with in- fered the following prayer: President pro tempore. structions, McConnell Amendment No. Let us pray. Mr. TILLIS thereupon assumed the 1260, to change the enactment date. Eternal God, You are our light and Chair as Acting President pro tempore. McConnell Amendment No. 1261 (the salvation, and we are not afraid. You instructions (Amendment No. 1260) of f protect us from danger so we do not the motion to refer), of a perfecting na- tremble. RESERVATION OF LEADER TIME ture. Mighty God, You are not intimidated The ACTING PRESIDENT pro tem- McConnell Amendment No. 1262 (to by the challenges that confront our Na- pore. -

The Curious Case of the Bradley Center, 27 Marq

Marquette Sports Law Review Volume 27 Article 2 Issue 2 Spring The urC ious Case of the Bradley Center Matthew .J Parlow Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Repository Citation Matthew J. Parlow, The Curious Case of the Bradley Center, 27 Marq. Sports L. Rev. 271 (2017) Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw/vol27/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GANN 27.1 (DO NOT DELETE) 7/19/17 10:04 AM ARTICLES THE CURIOUS CASE OF THE BRADLEY CENTER MATTHEW J. PARLOW* I. INTRODUCTION On March 5, 1985, Jane Bradley Pettit—along with her husband, Lloyd Pettit—announced that she was going to pay for the construction of a new sports arena, the Bradley Center, and donate it to the people of the State of Wisconsin so that they could enjoy and benefit from a state-of-the-art sports facility.1 The announcement was met with much enthusiasm, appreciation, and even marvel due to Mrs. Pettit’s incredible generosity.2 But few, if any, seemed to fully understand and appreciate how unique and extraordinary Mrs. Pettit’s gift was and would become. This lack of awareness was due to at least a few contextual factors. Up until the time of Mrs. Pettit’s announcement, the United States and Canada—where all of the teams in the four major profes- sional sports leagues played3—experienced only a modest number of new * Dean and Donald P. -

The Irish in Baseball ALSO by DAVID L

The Irish in Baseball ALSO BY DAVID L. FLEITZ AND FROM MCFARLAND Shoeless: The Life and Times of Joe Jackson (Large Print) (2008) [2001] More Ghosts in the Gallery: Another Sixteen Little-Known Greats at Cooperstown (2007) Cap Anson: The Grand Old Man of Baseball (2005) Ghosts in the Gallery at Cooperstown: Sixteen Little-Known Members of the Hall of Fame (2004) Louis Sockalexis: The First Cleveland Indian (2002) Shoeless: The Life and Times of Joe Jackson (2001) The Irish in Baseball An Early History DAVID L. FLEITZ McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Fleitz, David L., 1955– The Irish in baseball : an early history / David L. Fleitz. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-3419-0 softcover : 50# alkaline paper 1. Baseball—United States—History—19th century. 2. Irish American baseball players—History—19th century. 3. Irish Americans—History—19th century. 4. Ireland—Emigration and immigration—History—19th century. 5. United States—Emigration and immigration—History—19th century. I. Title. GV863.A1F63 2009 796.357'640973—dc22 2009001305 British Library cataloguing data are available ©2009 David L. Fleitz. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. On the cover: (left to right) Willie Keeler, Hughey Jennings, groundskeeper Joe Murphy, Joe Kelley and John McGraw of the Baltimore Orioles (Sports Legends Museum, Baltimore, Maryland) Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Je›erson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Acknowledgments I would like to thank a few people and organizations that helped make this book possible. -

Baseball Broadcasting in the Digital Age

Baseball broadcasting in the digital age: The role of narrative storytelling Steven Henneberry CAPSTONE PROJECT University of Minnesota School of Journalism and Mass Communication June 29, 2016 Table of Contents About the Author………………………………………………………………………………… 3 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………… 4 Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………………… 5 Introduction/Background…………………………………………………………………… 6 Literature Review………………………………………………………………………………… 10 Primary Research Studies Study I: Content Analysis…………………………………………………………… 17 Study II: Broadcaster Interviews………………………………………………… 31 Study III: Baseball Fan Interviews……………………………………………… 48 Conclusion/Recommendations…………………………………………………………… 60 References………………………………………………………………………………………….. 65 Appendix (A) Study I: Broadcaster Biographies Vin Scully……………………………………………………………………… 69 Pat Hughes…………………………………………………………………… 72 Ron Coomer…………………………………………………………………… 72 Cory Provus…………………………………………………………………… 73 Dan Gladden…………………………………………………………………… 73 Jon Miller………………………………………………………………………… 74 (B) Study II: Broadcaster Interview Transcripts Pat Hughes…………………………………………………………………… 75 Cory Provus…………………………………………………………………… 82 Jon Miller……………………………………………………………………… 90 (C) Study III: Baseball Fan Interview Transcripts Donna McAllister……………………………………………………………… 108 Rick Moore……………………………………………………………………… 113 Rowdy Pyle……………………………………………………………………… 120 Sam Kraemer…………………………………………………………………… 121 Henneberry 2 About the Author The sound of Chicago Cubs baseball has been a near constant part of Steve Henneberry’s life. -

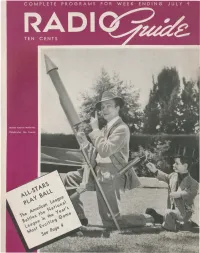

Radio Guide's Instant Program Locator Alka-Seltzer

AEA87BDC tener wants to know how the story ends. The other camp insists that the end be left untold. Doubles Your Radio Enjoyment Peeking behind the scenes, we see the motion-picture moguls on 731 PLYMOUTH COURT the one side attempting to harness CHICAGO, ILLINOIS radio so that it will fill their thea ters. Their device has been to pre It Looks Like sent their stars in a cleverly drama Politics Again tized "trailer" which was supposed to stir up our curiosity so that we Is the farmer's radio entertain would run to the nearest theater to ment going the way 01 his hogs and learn how the villain was loiled his wheat? The same Congress and virtue remained triumphant. which took away his right to plant There are clear indications, how as much cotton as he wanted to ever, that listeners are beginning plant, and which took away his to resent these strong-arm methods. right to raise as many head 01 live In their behalf, radio producers are stock as he wanted to raise is in demanding the lull story or none at the process 01 deciding that he can all. During the summer months, the not hear all the broadcasts he battle will be lought and a decision would like to hear. reached. Most American farmers are han But we still remain curious. dicapped by being at a distance Which is better entertainment, real from the powerful transmitters. ly? Do you want the complete During daylight hours, summer story or just enough to give you a heat and kindred hobgoblins blast taste? II you heard the whole story his reception with static. -

Chicago White Sox Charities Lots 1-52

CHICAGO WHITE SOX CHARITIES LOTS 1-52 Chicago White Sox Charities (CWSC) was launched in 1990 to support the Chicagoland community. CWSC provides annual financial, in-kind and emotional support to hundreds of Chicago-based organizations, including those who lead the fight against cancer and are dedicated to improving the lives of Chicago’s youth through education and health and well- ness programs and offer support to children and families in crisis. In the past year, CWSC awarded $2 million in grants and other donations. Recent contributions moved the team’s non-profit arm to more than $25 million in cumulative giving since its inception in 1990. Additional information about CWSC is available at whitesoxcharities.org. 1 Jim Rivera autographed Chicago White Sox 1959 style throwback jersey. Top of the line flannel jersey by Mitchell & Ness (size 44) is done in 1959 style and has “1959 Nellie Fox” embroi- dered on the front tail. The num- ber “7” appears on both the back and right sleeve (modified by the White Sox with outline of a “2” below). Signed “Jim Rivera” on the front in black marker rating 8 out of 10. No visible wear and 2 original retail tags remain affixed 1 to collar tag. Includes LOA from Chicago White Sox: EX/MT-NM 2 Billy Pierce c.2000s Chicago White Sox ($150-$250) professional model jersey and booklet. Includes pinstriped jersey done by the team for use at Old- Timers or tribute event has “Sox” team logo on the left front chest and number “19” on right. Num- ber also appears on the back. -

Major League Baseball

Appendix 1 to Sports Facility Reports, Volume 4, Number 1 ( Copyright 2003, National Sports Law Institute of Marquette University Law School) MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL Note: Information complied from Sports Business News, Forbes.com, Lexis-Nexis, and other sources published on or before June 6, 2003. Team Principal Owner Most Recent Purchase Price Current Value ($/Mil) ($/Mil) Percent Increase/Decrease From Last Year Anaheim Angels Walt Disney Co. 183.5 (2003) $225 (+15%) Stadium ETA Cost % Facility Financing (millions) Publicly Financed Edison 1966 $24 100% In April 1998, Disney completed a $117 M renovation. International Field Disney contributed $87 M toward the project while the of Anaheim City of Anaheim contributed $30 M through the retention of $10 M in external stadium advertising and $20 M in hotel taxes and reserve funds. UPDATE In May 2003, the Anaheim Angels made history by becoming the first American based professional sports team to be owned by an individual of Latino decent. Auturo Moreno, an Arizona businessman worth an estimated $940 million, bought the Angels for $183.5 million. Moreno, one of eleven children, is the former owner of a minor league baseball team and was once a minority owner of the Arizona Diamondbacks. NAMING RIGHTS The Anaheim Angels currently play at Edison International Field of Anaheim. On September 15, 1997, Edison International entered into a naming-rights agreement that will pay the Angels $50 million over 20 years with an average annual payout of $2.5 million. The naming-rights agreement expires in 2018. Team Principal Owner Most Recent Purchase Price Current Value ($/Mil) ($/Mil) Percent Increase/Decrease From Last Year Arizona Jerry Colangelo $130 (1995) $269 (-1%) Diamondbacks Stadium ETA Cost % Facility Financing (millions) Publicly Financed Bank One Ballpark 1998 $355 71% The Maricopa County Stadium District provided $238 M for the construction through a .25% increase in the county sales tax from April 1995 to November 30, 1997. -

Wrigley Field 1060 W

LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT Wrigley Field 1060 W. Addison St. Preliminary Landmark recommendation approved by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, November 1, 2000, and revised March 6, 2003 CITY OF CHICAGO Richard M. Daley, Mayor Department of Planning and Development Alicia Mazur Berg, Commissioner Cover: An aerial view of Wrigley Field. Above: Wrigley Field is located in the Lake View community area on Chicago’s North Side. The Commission on Chicago Landmarks, whose nine members are appointed by the Mayor, was established in 1968 by city ordinance. The Commission is responsible for recommending to the City Council which individual buildings, sites, objects, or districts should be designated as Chicago Landmarks, which protects them by law. The landmark designation process begins with a staff study and a preliminary summary of information related to the potential designation criteria. The next step is a preliminary vote by the land- marks commission as to whether the proposed landmark is worthy of consideration. This vote not only initiates the formal designation process, but it places the review of city permits for the property under the jurisdiction of the Commission until a final landmark recommendation is acted on by the City Council. This Landmark Designation Report is subject to possible revision and amendment during the designation process. Only language contained within the designation ordinance adopted by the City Council should be regarded as final. Wrigley Field 1060 W. Addison St. (bounded by Addison, Clark, Sheffield, Waveland, and the Seminary right of way) Built: 1914 Architects: Zachary T. and Charles G. Davis Alterations: 1922, 1927-28, 1937, and 1988 “One of the most beloved athletic facilities in the country . -

Extensions of Remarks

June 1, 1988 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 13187 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS A NEW PARTNERSHIP FOR democratic neighbors to resort to armed widely despised thug into a symbol of resist PLURALISM AND PROSPERITY force. ance to Yankee imperialism, and generate Had previous administrations accepted considerable concern on the part of our the essential truth of these propositions and allies abroad. HON. ROBERT G. TORRICELU acted accordingly, then perhaps we would Similarly, we must recognize that in Nica OF NEW JERSEY not now be saddled with a Sandinista regime ragua we have a far better chance of achiev IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES in Nicaragua that has threatened the peace ing our objectives and advancing the cause and stability of Central America. Wednesday, June 1, 1988 of democracy at the negotiating table than Had earlier administrations more actively on the battlefield. Mr. TORRICELLI. Mr. Speaker, a few days promoted democracy in Cuba, then perhaps But while opposing the resumption of ago our colleague, the gentleman from New we would not now be faced with a Soviet military aid to the contras-both because it York [Mr. SOLARZ], delivered an address on ally 90 miles from our own shores. is counterproductive and because it sets a It is, of course, one thing to acknowledge dangerous precedent for interventionism the promotion and preservation of democracy the general desirability of democracy, and in Latin America before the Democratic elsewhere-we must not be indifferent to quite another to figure out the best way to the struggle of Nicaraguan democrats for Party's platform committee. promote and sustain it. -

University Library 11

I ¡Qt>. 565 MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL PRINCIPAL PLAY-BY-PLAY ANNOUNCERS: THEIR OCCUPATION, BACKGROUND, AND PERSONAL LIFE Michael R. Emrick A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY June 1976 Approved by Doctoral Committee DUm,s¡ir<y »»itti». UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 11 ABSTRACT From the very early days of radio broadcasting, the descriptions of major league baseball games have been among the more popular types of programs. The relationship between the ball clubs and broadcast stations has developed through experimentation, skepticism, and eventual acceptance. The broadcasts have become financially important to the teams as well as the advertisers and stations. The central person responsible for pleasing the fans as well as satisfying the economic goals of the stations, advertisers, and teams—the principal play- by-play announcer—had not been the subject of intensive study. Contentions were made in the available literature about his objectivity, partiality, and the influence exerted on his description of the games by outside parties. To test these contentions, and to learn more about the overall atmosphere in which this focal person worked, a study was conducted of principal play-by-play announcers who broadcasted games on a day-to-day basis, covering one team for a local audience. With the assistance of some of the announcers, a survey was prepared and distributed to both announcers who were employed in the play-by-play capacity during the 1975 season and those who had been involved in the occupation in past seasons.