The Curious Case of the Bradley Center, 27 Marq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yankee Stadium and the Politics of New York

The Diamond in the Bronx: Yankee Stadium and The Politics of New York NEIL J. SULLIVAN OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS THE DIAMOND IN THE BRONX This page intentionally left blank THE DIAMOND IN THE BRONX yankee stadium and the politics of new york N EIL J. SULLIVAN 1 3 Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paolo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Copyright © 2001 by Oxford University Press Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available. ISBN 0-19-512360-3 135798642 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper For Carol Murray and In loving memory of Tom Murray This page intentionally left blank Contents acknowledgments ix introduction xi 1 opening day 1 2 tammany baseball 11 3 the crowd 35 4 the ruppert era 57 5 selling the stadium 77 6 the race factor 97 7 cbs and the stadium deal 117 8 the city and its stadium 145 9 the stadium game in new york 163 10 stadium welfare, politics, 179 and the public interest notes 199 index 213 This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgments This idea for this book was the product of countless conversations about baseball and politics with many friends over many years. -

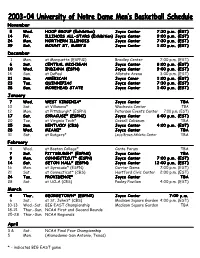

04 Mbb Schedule

2003-04 University of Notre Dame Men’s Basketball Schedule November 5 Wed. HOOP GROUP (Exhibition) Joyce Center 7:30 p.m. (EST) 14 Fri. ILLINOIS ALL-STARS (Exhibition) Joyce Center 9:00 p.m. (EST) 24 Mon. NORTHERN ILLINOIS Joyce Center 7:30 p.m. (EST) 29 Sat. MOUNT ST. MARY’S Joyce Center 1:00 p.m. (EST) December 1 Mon. at Marquette (ESPN2) Bradley Center 7:00 p.m. (EST) 6 Sat. CENTRAL MICHIGAN Joyce Center 8:00 p.m. (EST) 10 Wed. INDIANA (ESPN) Joyce Center 9:00 p.m. (EST) 14 Sun. at DePaul Allstate Arena 3:00 p.m. (EST) 21 Sun. AMERICAN Joyce Cener 1:00 p.m. (EST) 23 Tue. QUINNIPIAC Joyce Center 7:30 p.m. (EST) 28 Sun. MOREHEAD STATE Joyce Center 1:00 p.m. (EST) January 7 Wed. WEST VIRGINIA* Joyce Center TBA 10 Sat. at Villanova* Wachovia Center TBA 12 Mon. at Pittsburgh* (ESPN) Petersen Events Center 7:00 p.m. (EST) 17 Sat. SYRACUSE* (ESPN2) Joyce Center 6:00 p.m. (EST) 20 Tue. at Virginia Tech* Cassell Coliseum TBA 25 Sun. KENTUCKY (CBS) Joyce Center 4:00 p.m. (EST) 28 Wed. MIAMI* Joyce Center TBA 31 Sat. at Rutgers* Louis Brown Athletic Center TBA February 4 Wed. at Boston College* Conte Forum TBA 7 Sat. PITTSBURGH* (ESPN2) Joyce Center TBA 9 Mon. CONNECTICUT* (ESPN) Joyce Center 7:00 p.m. (EST) 14 Sat. SETON HALL* (ESPN) Joyce Center 12:00 p.m. (EST) 16 Mon. at Syracuse* (ESPN) Carrier Dome 7:00 p.m. -

University of Cincinnati News Record. Friday, February 2, 1968. Vol. LV

\LI T , Vjb, i ;-/ Cineinneti, Ohio; Fr~day, February 2, 1968' No. 26 Tickets. For Mead Lectilres ..". liM,ore.ea. H' d''Sj·.L~SSI., .' F"eet...-< II Cru~cialGame.~ Gr~atestNeed'Of Young; Comments -MargQret Mead Are Ava'ilab'le by Alter Peerless '\... that the U.S. was fighting an evil Even before the Bearcatsget enemy, but now-people can see "In the, past fifty years there a chance to recover from the'" for themselves that in' war both has been too much use of feet, sides kill and mutilate other peo- _ shell shock of two conference and not enough use' of heads," ple. road loses in a row, tihey baY~,to -said Dr: Margaret Mead, inter- Another reason this generation play 'the most 'Crucial' game' of nationally kn'own· anthropologist, is unhappy is because the num- in her lecture at the YMCA.'last bers involved are smaller. In the yea!,~at Louisville. Tuesday., . Wednesday n i gh t's Bradley World War II, the Americans had Dr. Mead .spoke on "College no sympathy for war victims. game goes down as' a wasted ef- Students' Disillusionment: Viet- They could not comprehend the fort. Looking strong at the begin- nam War and National Service." fact that six' .million Jews were· ningthe 'Cats faded in the final She said that this is not the first ' killed, or that an entire city was period when 'young people have wiped out. The horror of World minutes, missing several shots. , demonstrated for 'good causes. Jim Ard played welleonsidering War II was so great, America There have' been peace marches, could not react to it. -

Visit-Milwaukee-Map-2018.Pdf

19 SHERIDAN’S BOUTIQUE HOTEL & CAFÉ J7 38 HISTORIC MILWAUKEE, INC. C3 57 77 97 MILWAUKEE PUBLIC MARKET C3 117 WATER STREET BREWERY C2 ACCOMMODATIONS BLU C3 FUEL CAFÉ D1 135 MILWAUKEE HARLEY-DAVIDSON I6 5133 S. Lake Dr., Cudahy 235 E. Michigan St., Milwaukee 424 E. Wisconsin Ave., Milwaukee 818 E. Center St., Milwaukee 400 N. Water St., Milwaukee 1101 N. Water St., Milwaukee 11310 W. Silver Spring Rd., Milwaukee (414) 747-9810 | sheridanhouseandcafe.com (414) 277-7795 | historicmilwaukee.org (414) 298-3196 | blumilwaukee.com (414) 372-3835 | fuelcafe.com (414) 336-1111 | milwaukeepublicmarket.org (414) 272-1195 | waterstreetbrewery.com (414) 461-4444 | milwaukeeharley.com 1 ALOFT MILWAUKEE DOWNTOWN C2 Well appointed, uniquely styled guest rooms Offering architectural walking tours through Savor spectacular views from the top of the Pfi ster Hotel Fuel offers killer coffee and espresso drinks, great Visit Milwaukee’s most unique food destination! In the heart of the entertainment district, Visit Milwaukee Harley, a pristine 36K sq ft 1230 N. Old World 3rd St., Milwaukee with high end furnishings. Seasonal menu, casual downtown Milwaukee and its historic neighborhoods. while enjoying a fi ne wine or a signature cocktail. sandwiches, paninis, burritos, and more. Awesome A year-round indoor market featuring a bounty of Milwaukee’s fi rst brew pub serves a variety of showroom fi lled with American Iron. Take home (414) 226-0122 | aloftmilwaukeedowntown.com gourmet fare. Near downtown and Mitchell Int’l. Special events and private tours available. t-shirts and stickers. It’s a classic! the freshest and most delicious products. award-winning craft brews served from tank to tap. -

Assembly Journal Eighty-Seventh Regular Session

_ STATE OF WISCONSIN Assembly Journal Eighty-Seventh Regular Session MONDAY, January 7, 1985. 2:00 P.M. The assembly was called to order by the chief clerk of COMMUNICATIONS the 1983 session, Joanne Duren. State of Wisconsin The prayer was offered by Reverend M. Ted Steege, Elections Board Director of Lutheran Office for Public Policy in Madison Wisconsin, 116 West Washington Avenue, Madison. January 4, 1985 "Eternal God, Ruler of the Universe, in whom we live To the Honorable the Assembly: and move and have our being: We give thanks, for in you all things are made new. As we enter a new session of this Dear Ms. Duren: great decision-making body, we rejoice in the gifts of Please be advised that the attached is a listing of those creation with which our state is so abundantly blessed -- persons elected Representative to the Assembly at the river and stream; forest and glade; soil and sky; a diverse General Election held in the State of Wisconsin on people of energy, enterprise and concern. Bless the November 6, 1984. members of this legislature, who are called to be good stewards of the power which has been placed into their Also, enclosed is a copy of the signed official canvass hands for the well-being of all. Bless all the legislators — for the election of Representative to the Assembly. women and men, people of diverse races and ethnic Very truly yours, heritage, people of differing economic interests, people KEVIN J. KENNEDY who call you by a variety of names or who do not call on Executive Secretary you at all — that together they may serve the cause of justice and peace for all the people. -

Making History in Milwaukee Religion and Gay Rights in Wisconsin

WINTER 2015-2016 ma Vel Phillips: Making History in Milwaukee Religion and Gay Rights in Wisconsin BOOK EXCERPT Milwaukee Mayhem MAKE A PLAN MAKE RENCE "I have proudly contributed to the Wisconsin Historical Society for years. I also created a plan for added legacy support through a bequest in my will. I did this as a sign of my deep appreciation for everything that Society staff and volunteers do to collect, preserve and share Wisconsin's stories." -John Evans, Robert B.L. Murphy Legacy Circle member The above image of the Ames Family Tree is adapted from Wisconsin Historical Society Image #5049 1. A Planned Gift Of Estate ASSetS Can Robert B.L. Murphy Legacy Circle members are Society Offer You Financial Advantages and supporters who planned estate gifts Provide Lasting Support for the Society we hold their pledges in very high rep-^ and respect their enduring commitmen Wisconsin Historical FOUNDATION To ask about joining this distinguished group contact: (608) 261-9364 or [email protected] WISCONSIN MAGAZINE OF HISTORY A Gastronomic Forecast Dire was the clang of plate, of knife and fork. That merciless fell, like tomahawk, to work. WISCONSIN — Dr. Wotcot's Peter Pindar. HISTORICAL CREAM OF TOMATO SOCIETY ROAST TURKEY Director, Wisconsin Historical Society Press Kathryn L. Borkowski NEAPOLITAN ICE CREAM ASSORTED CAKE BENT'S CRAC KERS CHEESE Editorial COFFEE Jane M. De Broux, Sara Phillips, Elizabeth Wyckoff From the Maennerchor Managing Editor Diane T. Drexler First Tenor First Bass CHAS. HOEBEL JACOB ESSER FRANK C. BLIED HERMAN GAERTNER Image Researcher WJYl. JOACHIM John H. Nondorf Second Tenor Second Bass A. -

Wisconsin Briefs from the Legislative Reference Bureau

Wisconsin Briefs from the Legislative Reference Bureau Brief 12−1 April 2012 INITIATIVE, REFERENDUM, AND RECALL IN WISCONSIN INTRODUCTION government bodies) may submit petitions This brief summarizes the laws relating to proposing legislation. the initiative, referendum, and recall in While Section 9.20, Wisconsin Statutes, is Wisconsin. titled “Direct legislation,” the initiative Unlike many states, Wisconsin does not process in Wisconsin cities and villages is have a statewide initiative process, but actually an indirect form. A direct initiative residents of cities and villages may initiate process enables a measure to be placed directly legislation by petition. In addition, statewide on the ballot if a sufficient number of and local referenda are required in numerous signatures are gathered on petitions, thus circumstances. The state legislature or any enabling citizens to bypass the legislative city, village, or county may also enact a law or body completely and avoid any threat of an ordinance contingent upon approval at a executive veto. referendum. The state legislature or these local In contrast, under the indirect initiative governing bodies may, at their discretion, process available to residents of Wisconsin submit questions to the voters in the form of cities and villages, electors may propose, via advisory referenda. petition, that the city common council or Citizens may use the recall process to village board pass a desired ordinance or remove almost any statewide or local resolution without amendment. In addition, s. government elective official. As with an 66.0101 (6) permits electors to initiate the initiative, the recall process is started via enactment, amendment, or repeal of city or petition. -

Eric Church Doesn't Back Down on Holdin' My Own

ERIC CHURCH DOESN’T BACK DOWN ON HOLDIN’ MY OWN TOUR Standing behind his vow to put face-value tickets in fans’ hands, Church cancels secondary market ticket orders and releases them back to the public - Tuesday, Feb 21 at NOON. Tickets available while supplies last for Eric’s show at STAPLES Center in Los Angeles on March 31 at www.AXS.com. Nashville, Tenn. – After witnessing the three-hour, two-set marathon show at Brooklyn’s Barclays Center merely weeks ago, Rolling Stone professed, “Eric Church sets the bar.” The exchange in energy with the audience and passion that fuels the man behind the CMA’s Album of the Year is an earned one after years of putting his fans first. Whether it is the dozens in attendance at his first performance in Bethel, New York or the 15,842 in attendance for last month’s breezy night in Brooklyn, it is that unrivaled dedication to surpassing their expectations that is driving another mission: ensuring fans’ hard-earned money is spent fairly on face-value tickets at each and every stop on his 60-plus city Holdin’ My Own Tour. Throughout the Holdin’ My Own Tour, Eric and his team have systematically identified, cancelled and released tickets back to the public that were identified as scalper tickets. Already on the tour, Eric’s management team used a proprietary program to release thousands of tickets back to the public and fans in markets like Brooklyn, Philadelphia, Toronto, Vancouver and Boston. On Feb. 21 at noon local time, the team will release to the official ticketing website all tickets identified as scalper-purchased for the remaining markets back to the public. -

Village of Weston Meeting Notice & Agenda

VILLAGE OF WESTON MEETING NOTICE & AGENDA of a Village Board, Commission, Committee, Agency, Corporation, Quasi-Municipal Corporation, or Sub-unit thereof Meeting of: BOARD OF TRUSTEES Members: White {c}, Berger, Ermeling, Jaeger, Porlier, Schuster, Ziegler Location: Weston Municipal Center (5500 Schofield Ave); Board Room Date/Time: Monday, August 4th, 2014 @ 6:00 P.M. 1. Call to Order. 1.1 Pledge of Allegiance. 1.2 Roll Call of Attendance. 2. Comments from the public. 3. Communications. 3.1 Recommendation from Clerk to acknowledge and place on file meeting minutes from all standing and non- standing committees, commissions or boards. 4. Consent Items for Consideration. 4.1 Approval of prior meeting minutes of 07/21/14 4.2 Approval of Vouchers. 4.3 Recommendation from Chief Sparks to approve operator licenses. 4.4 Recommendation from Village Clerk to approve Kriston Koffler as Agent for Kwik Trip 356, 5603 Bus. Hwy. 51 4.5 Recommendation from Village Clerk to approve request for Class B Beer and Class B Liquor License for Kim’s Wisconsin, LLC, Pine Ridge Family Restaurant (3705 Schofield Avenue), with contingency as listed in the attached Request for Consideration. 4.6 Recommendation from Finance Committee to approve an amendment to the FY2014 budget to continue Clerk Department Administrative Assistant position funding partnership with the WI Dept. of Vocational Rehabilitation at the expense of not to exceed $1,200. 4.7 Recommendation from Finance Committee to approve budget amendments to Room Tax Fund 29 and assign and increase expenditure authority in FY2014. 4.8 Recommendation from staff to approve Change Order #1 from Fahrner Asphalt Sealers for crack sealing on additional streets for an amount up to $14,800. -

New York Sun New York

PAGE 2 MONDAY, JUNE 13, 2005 THE NEW YORK SUN NEW YORK PAGE 2 MONDAY, JUNE 13, 2005 THE NEW YORK SUN CAFTA Sparks Divided Reactions in City’s Caribbean Communities By DANIELA GERSON lines of those who say the agreement cultural workers in the Dominican ers in the garment trades. Last month, NEW StaffYORK Reporter of the Sun will enable the poor countries to enter Republic as well, he said. when President Fernandez of the Do- In neighborhoods where events the global market, and those who say “Most of the things that we sell in minican Republic came to New York across the Caribbean Sea are often felt American interests will abuse them. bodegas, like fruit and vegetables to promote CAFTA, Mr. Laranceunt as keenly as developments here, the A leading organizer of the support- and agriculture, these products stood in front of City College protest- Central American Free Trade Agree- ers is a Dominican-born entrepre- come from those countries at a very ing the pact. ment has sparked an intense and divid- “We wanted to let the president ed reaction. know that this treaty does not benefit CAFTA Sparks Divided Reactions in City’s CaribbeanOne immigrant from Communities the Dominican the Dominican people in the Domini- Republic, Rafael Chavez, was so em- can Republic nor the people in the phatic in his opposition to CAFTA, as United States,” he said. Low-wage jobs By DANIELA GERSON lines of those who say the agreement cultural workers in the Dominicanthe pending erpacts in on the trade garment is known, trades. -

Stadium Development and Urban Communities in Chicago

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1996 Stadium Development and Urban Communities in Chicago Costas Spirou Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Spirou, Costas, "Stadium Development and Urban Communities in Chicago" (1996). Dissertations. 3649. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3649 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1996 Costas Spirou LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO STADIUM DEVELOPMENT AND URBAN COMMUNITIES IN CHICAGO VOLUME 1 (CHAPTERS 1 TO 7) A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY BY COSTAS S. SPIROU CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JANUARY, 1997 Copyright by Costas S. Spirou, 1996 All rights reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The realization and completion of this project would not have been possible without the contribution of many. Dr. Philip Nyden, as the Director of the Committee provided me with continuous support and encouragement. His guidance, insightful comments and reflections, elevated this work to a higher level. Dr. Talmadge Wright's appreciation of urban social theory proved inspirational. His knowledge and feedback aided the theoretical development of this manuscript. Dr. Larry Bennett of DePaul University contributed by endlessly commenting on earlier drafts of this study. -

2019-2020 Wisconsin Blue Book

Significant events in Wisconsin history First nations 1668 Nicolas Perrot opened fur trade Wisconsin’s original residents were with Wisconsin Indians near Green Bay. Native American hunters who arrived 1672 Father Allouez and Father Louis here about 14,000 years ago. The area’s André built the St. François Xavier mis- first farmers appear to have been the sion at De Pere. Hopewell people, who raised corn, 1673 Louis Jolliet and Father Jacques squash, and pumpkins around 2,000 Marquette traveled the length of the years ago. They were also hunters and Mississippi River. fishers, and their trade routes stretched 1679 to the Atlantic Coast and the Gulf of Daniel Greysolon Sieur du Lhut Mexico. Later arrivals included the (Duluth) explored the western end of Chippewa, Ho-Chunk (Winnebago), Lake Superior. Mohican/Munsee, Menominee, Oneida, 1689 Perrot asserts the sovereignty of Potawatomi, and Sioux. France over various Wisconsin Indian tribes. Under the flag of France 1690 Lead mines are discovered in Wis- The written history of the state began consin and Iowa. with the accounts of French explorers. 1701–38 The Fox Indian Wars occurred. The French explored areas of Wiscon- 1755 Wisconsin Indians, under Charles sin, named places, and established trad- Langlade, helped defeat British Gen- ing posts; however, they were interested eral Braddock during the French and in the fur trade, rather than agricultural Indian War. settlement, and were never present in 1763 large numbers. The Treaty of Paris is signed, mak- ing Wisconsin part of British colonial 1634 Jean Nicolet became the first territory. known European to reach Wisconsin.