Unreasonable Access: Disguised Issue Advocacy and the First Amendment Status of Broadcasters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protests Say: Abortion Is a Woman's Right to Choose!

· AUSTRALIA $1.50 · CANADA $1.25 · FRANCE 1.00 EURO · NEW ZEALAND $1.50 · SWEDEN KR10 · UK £.50 · U.S. $1.00 INSIDE How attempts to shut abortion clinics were defeated in early ’90s — PAGE 9 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF WORKING PEOPLE VOL. 73/NO. 23 JUNE 15, 2009 Washington Protests say: abortion is a seeks new sanctions woman’s right to choose! Vigils condemn killing of clinic doctor in Kansas on N. Korea BY TED LEONARD BY BEN Joyce AND MAGGIE TROWE The U.S. government and its impe- WICHITA, Kansas—Just hours af- rialist allies have condemned a recent ter Dr. George Tiller was shot to death, nuclear test and missile launches by about 400 people joined a candlelight North Korea. Washington and Tokyo vigil here May 31 to protest his killing are pressing for a UN resolution to and defend a woman’s right to choose impose more punitive sanctions and abortion. other measures against the country In nearby Lawrence 150 people for daring to challenge their dictates. participated in a similar vigil that Susan Rice, the U.S. ambassador to night. In the days following the doc- the United Nations, said June 1 that tor’s death, similar events took place the UN Security Council was “mak- throughout Kansas and the Midwest, ing progress” in coming up with a and across the country. new resolution that may involve new sanctions on North Korea. A partial MOBILIZE TO DEFEND draft of the resolution obtained by the Associated Press May 29 calls on WOMEN’S RIGHT TO CHOOSE! all governments “immediately to en- Editorial —p. -

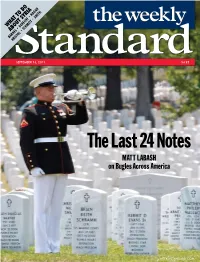

The Weekly Standard…Don’T Settle for Less

“THE ORACLE OF AMERICAN POLITICS” — Wolf Blitzer, CNN …don’t settle for less. POSITIONING STATEMENT The Weekly Standard…don’t settle for less. Through original reporting and prose known for its boldness and wit, The Weekly Standard and weeklystandard.com serve an audience of more than 3.2 million readers each month. First-rate writers compose timely articles and features on politics and elections, defense and foreign policy, domestic policy and the courts, books, art and culture. Readers whose primary common interests are the political developments of the day value the critical thinking, rigorous thought, challenging ideas and compelling solutions presented in The Weekly Standard print and online. …don’t settle for less. EDITORIAL: CONTENT PROFILE The Weekly Standard: an informed perspective on news and issues. 18% Defense and 24% Foreign Policy Books and Arts 30% Politics and 28% Elections Domestic Policy and the Courts The value to The Weekly Standard reader is the sum of the parts, the interesting mix of content, the variety of topics, type of writers and topics covered. There is such a breadth of content from topical pieces to cultural commentary. Bill Kristol, Editor …don’t settle for less. EDITORIAL: WRITERS Who writes matters: outstanding political writers with a compelling point of view. William Kristol, Editor Supreme Court and the White House for the Star before moving to the Baltimore Sun, where he was the national In 1995, together with Fred Barnes and political correspondent. From 1985 to 1995, he was John Podhoretz, William Kristol founded a senior editor and White House correspondent for The new magazine of politics and culture New Republic. -

Randall A. Terry, Founder, Operation Rescue

This is me presenting John Paul II a copy of my book and video, Operation Rescue. I spoke in the Vatican at an international pro-life convention, and I urged leaders from around the world to take Operation Rescue to their own country. This was October, 1991. Mr. Newman told the Trademark Office he had been using the name Operation Rescue since July, 1991. As I will now prove, Mr. Newman’s filing with the Trademark Office, as well as his use of the name Operation Rescue is completely fraudulent. Randall A. Terry, Founder, Operation Rescue 1 In addition to finances, Mr. Newman has received unearned notoriety and Operation Rescue “Identity Theft” credibility with the media and the public due to the respect that the name Operation Rescue earned in the late 1980s and early 1990s, long before Troy Newman was involved in the pro-life movement, much less the mission and Suit Filed against Mr. Troy Newman by Mr. Randall Terry, activities of Operation Rescue. Founder of Operation Rescue, in the U.S. Trademark Trial and Appeal Board. I filed this suit because in April of 2007, I sought to file a trademark of ownership of the name Operation Rescue with the Trademark Office. At that Mr. Newman is fraudulently raising money and sending out press time, my attorney informed me that Mr. Newman had filed for ownership in December of 2006. releases in the name of Operation Rescue; Mr. Newman lied on the oath he filed with the Trademark Office Mr. Newman Lied By Randall Terry In his sworn statement to the Federal Trademark Office, Mr. -

Issues Raised by the Abortion Rescue Movement Charles E

Notre Dame Law School NDLScholarship Journal Articles Publications 1989 Issues Raised by the Abortion Rescue Movement Charles E. Rice Notre Dame Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship Part of the Health Law and Policy Commons, and the Human Rights Law Commons Recommended Citation Charles E. Rice, Issues Raised by the Abortion Rescue Movement, 23 Suffolk U. L. Rev. 15 (1989). Available at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship/316 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ISSUES RAISED BY THE ABORTION RESCUE MOVEMENT Charles E. Rice* The civil rights protests of the fifties and sixties taught the nation about the relation of the enacted law to the higher law of justice. Though less favorably publicized, the abortion rescue movement provides another such teaching moment today. As with the civil rights protests, the abor- tion rescue movement involves ordinary people putting their bodies on the line-and in jail-to vindicate their conception of justice. The rescue movement raises issues that transcend the question of whether one ap- proves or disapproves of abortion. This paper examines what society might learn from the Operation Rescue movement about the weaknesses of our law. A Newsweek commentary entitled Operation Rescue captured the movement's essence: Abortion is the most painfully divisive issue in American public life, and after years of relative dormancy, it shows signs of erupting again. -

'Us Versus Them': Abortion and the Rhetoric of the New Right1

Retrospectives | 2 Spring 2013 ! ‘Us versus Them’: Abortion and the Rhetoric of the New Right1 Will Riddington* This paper analyses America's anti-abortion movement from a rhetorical perspective. It examines the rhetorical tactics used by conservative elites to galvanise the movement and traces their effect on the movement's response to anti-abortion violence in the late 1980s and early 1990. It concludes by arguing that the fusion of populist dichotomies and religious justifications had an ultimately negative effect on the movement, despite initial successes. It engages with a number of historiographical debates surrounding the emergence of the New Right and its place in the wider American political tradition. By analysing the anti-abortion movement, its motivations and its actions, this paper will argue that although the movement invoked a number of long-standing conservative themes, its invocation of populism relied on new rhetorical devices whose resonance derived from opposition to sixties liberalism. Historiographical debate also revolves around the relationship between New Right activists and the Republican party, some arguing that conservative grassroots activism dragged the GOP to the right, others that social issues were manipulated by Republican elites for electoral gain. It will argue that, at least in the case of the anti-abortion movement, the fundamentalist and evangelical Christians who joined the fray in the late 1970s !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! 1 This work was supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council [grant number AH/K502959/1]. * Will Riddington is a first-year doctoral student at the University of Cambridge. 86 Retrospectives | 2 Spring 2013 ! did so at the urging of the New Right and their pastors, rather than as part of a spontaneous grassroots uprising. -

The Last 24 Notes MATT LABASH on Bugles Across America

WHAT TO DO ABOUT SYRIA BARNES • GERECHT • KAGAN KRISTOL • SCHMITT • SMITH SEPTEMBER 16, 2013 $4.95 The Last 24 Notes MATT LABASH on Bugles Across America WWEEKLYSTANDARD.COMEEKLYSTANDARD.COM Contents September 16, 2013 • Volume 19, Number 2 2 The Scrapbook We’ll take the disposable Post, the march of science, & more 5 Casual Joseph Bottum gets stuck in the land of honey 7 Editorial The Right Vote BY WILLIAM KRISTOL Articles 9 I Came, I Saw, I Skedaddled BY P. J. O’ROURKE Decisive moments in Barack Obama history 7 10 Do It for the Presidency BY GARY SCHMITT Congress, this time at least, shouldn’t say no to Obama 12 What to Do About Syria BY FREDERICK W. K AGAN Vital U.S. interests are at stake 14 Sorting Out the Opposition to Assad BY LEE SMITH They’re not all jihadist dead-enders 16 Hesitation, Delay, and Unreliability BY FRED BARNES Not the qualities one looks for in a war president 17 The Louisiana GOP Gains a Convert BY MICHAEL WARREN Elbert Lee Guillory, Cajun noir Features 20 The Last 24 Notes BY MATT LABASH Tom Day and the volunteer buglers who play ‘Taps’ at veterans’ funerals across America 26 The Muddle East BY REUEL MARC GERECHT Every idea Obama had about pacifying the Muslim world turned out to be wrong Books & Arts 9 30 Winston in Focus BY ANDREW ROBERTS A great man gets a second look 32 Indivisible Man BY EDWIN M. YODER JR. Albert Murray, 1916-2013 33 Classical Revival BY MARK FALCOFF Germany breaks from its past to embrace the past 36 Living in Vein BY JOSHUA GELERNTER Remember the man who invented modern medicine 37 With a Grain of Salt BY ELI LEHRER Who and what, exactly, is the chef du jour? 39 Still Small Voice BY JOHN PODHORETZ Sundance gives birth to yet another meh-sterpiece 20 40 Parody And in Russia, the sun revolves around us COVER: An honor guard bugler plays at the burial of U.S. -

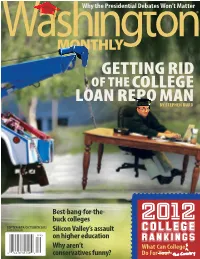

Getting Rid of Thecollege Loan Repo Man by STEPHEN Burd

Why the Presidential Debates Won’t Matter GETTING RID OF THECOLLEGE LOAN REPO MAN BY STEPHEN BURd Best-bang-for-the- buck colleges 2012 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2012 $5.95 U.S./$6.95 CAN Silicon Valley’s assault COLLEGE on higher education RANKINGS Why aren’t What Can College conservatives funny? Do For You? HBCUsHow do tend UNCF-member to outperform HBCUsexpectations stack in up successfully against other graduating students from disadvantaged backgrounds. higher education institutions in this ranking system? They do very well. In fact, some lead the pack. Serving Students and the Public Good: HBCUs and the Washington Monthly’s College Rankings UNCF “Historically black and single-gender colleges continue to rank Frederick D. Patterson Research Institute Institute for Capacity Building well by our measures, as they have in years past.” —Washington Monthly Serving Students and the Public Good: HBCUs and the Washington “When it comes to moving low-income, first-generation, minority Monthly’s College Rankings students to and through college, HBCUs excel.” • An analysis of HBCU performance —UNCF, Serving Students and the Public Good based on the College Rankings of Washington Monthly • A publication of the UNCF Frederick D. Patterson Research Institute To receive a free copy, e-mail UNCF-WashingtonMonthlyReport@ UNCF.org. MH WashMonthly Ad 8/3/11 4:38 AM Page 1 Define YOURSELF. MOREHOUSE COLLEGE • Named the No. 1 liberal arts college in the nation by Washington Monthly’s 2010 College Guide OFFICE OF ADMISSIONS • Named one of 45 Best Buy Schools for 2011 by 830 WESTVIEW DRIVE, S.W. The Fiske Guide to Colleges ATLANTA, GA 30314 • Named one of the nation’s most grueling colleges in 2010 (404) 681-2800 by The Huffington Post www.morehouse.edu • Named the No. -

42 Kansas History Assembling a Buckle of the Bible Belt: from Enclave to Powerhouse by Jay M

Immanuel Baptist Church, with its towering cross, in downtown Wichita, Kansas. Courtesy of Jay M. Price. Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 41 (Spring 2018): 42-61 42 Kansas History Assembling a Buckle of the Bible Belt: From Enclave to Powerhouse by Jay M. Price n Sunday, July 14, 1991, Bob Knight, mayor of Wichita, Kansas, had just delivered a talk at a local church when Chief of Police Rick Stone came up and warned him that “we’re going to have some very difficult circumstances tomorrow.” Operation Rescue, an antiabortion organization, intended to picket local abortion facilities. In particular, Operation Rescue leaders such as Randall Terry wanted to organize local and national antiabortion efforts to focus national attention on abortion providers such as George Tiller. Stone noted that “they’ll Oblock, they’ll protest, first of all, but they’ve been known to block entrances.” Knight responded that these actions “shouldn’t be insurmountable to enforce our laws.” If there were arrests, he presumed that ordinary law enforcement channels would suffice. The next morning, July 15, Knight received a call from Ryder Truck Rental concerned that protesters who had gathered outside Tiller’s office were being arrested and loaded into the company’s rented vehicles. In the days that followed, the arrests did not dissuade the protesters. In fact, the protests grew, and police efforts included helicopters flying overhead and blocking Kellogg Avenue. Initially, the protesters had envisioned a week-long series of events, including rallies and training in how to blockade the entrances to abortion clinics and intercept women going to the clinics. -

Disguised Issue Advocacy and the First Amendment Status of Broadcasters

Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 25 Volume XXV Number 1 Volume XXV Book 1 Article 3 2014 Unreasonable Access: Disguised Issue Advocacy and the First Amendment Status of Broadcasters Kerry L. Monroe Yale University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Kerry L. Monroe, Unreasonable Access: Disguised Issue Advocacy and the First Amendment Status of Broadcasters, 25 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J. 117 (2014). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol25/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Unreasonable Access: Disguised Issue Advocacy and the First Amendment Status of Broadcasters Cover Page Footnote Ph.D. candidate in Law, class of 2016, Yale University; J.D., 2010, University of Michigan Law School. I would like to thank Floyd Abrams, Jack Balkin, Vince Blasi, Molly Brady, Rebecca Crootof, Zach Herz, Eric Fish, Robert Post, Richard Primus, Reva Siegel, Gordon Silverstein, Rory Van Loo, and participants in the 2014 Freedom of Expression Scholars Conference at Yale Law School for their comments on earlier drafts of this Article. In the interest of full disclosure, I should note that I represented the broadcasters who were subject to the October 2012 FCC decisions discussed in this Article, along with my former colleagues at Covington & Burling LLP. -

Fulton John Sheen, American Roman Catholic

Evangelicals and Democracy in America: General Timeline 1927 – 1962: Robert “Bob” Reynolds Jones, Sr., an American Fundamentalist Christian evangelist, launches daily and weekly network programs on the East Coast.1 1927: Robert “Bob” Reynolds Jones, Sr. founds Bob Jones College in Bay County, FL. In 1947, the college moves to Greenville, SC, admits 2,500 students, and changes its name to Bob Jones University (BJU).2 1927: Father Charles Edward Coughlin, a Roman Catholic priest, gives first Catholic services on the radio. In 1930, CBS picks up Coughlin‟s radio show and broadcasts it over its national network, which is the first time such a program is broadcasted over a national network. In 1932, Coughlin strongly supports FDR‟s presidential bid – “Roosevelt or Ruin.” Within a few years, however, Coughlin becomes a vociferous critic of FDR. In 1934, Coughlin sets up the National Union for Social Justice Organization.3 In 1938, Coughlin “indirectly” sets up the Christian Front (via a 23 May 1938 Social Justice article) with the basic organizational unit being the “platoon.”4 Also in 1938, Coughlin publishes a version of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.5 Finally, in 1938, 10 November – Kristallnacht – Coughlin states, “Jewish persecution only followed after Christians first were persecuted.”6 1936: Father John Ryan, a Roman Catholic priest, social reformer, and university educator denounces Father Coughlin for his “ugly, cowardly and flagrant” attacks on FDR.7 1939: The National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) adopts its first industry code, which has provisions covering religion that are believed to have been an attempt to bar Father Coughlin from buying airtime.8 1941: The FCC establishes the Chain Broadcasting Regulations, which governs the licensing and content of chain broadcasting stations. -

2012 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTOR CANDIDATES (As of September 7, 2012)

2012 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTOR CANDIDATES (as of September 7, 2012) Constitution Party (write-in candidates) Pledged to Virgil H. Goode, Jr., of Virginia for President Joseph O. Henzler, of Indianapolis Audrey Queckboerner, of Leo Austin Teltoe, of Indianapolis Elyne Strauss, of Indianapolis Eric Johnson, of Bloomington Gary Queckboerner, of Leo Fred Bailey, of Fort Wayne Democratic Party: Pledged to Barack Obama of Illinois for President and Joe Biden of Delaware for Vice-President Clay M. Patton, of Valparaiso Michael Schmuhl, of South Bend Randy S. Schmidt, of Fort Wayne Jeffrey S. Fites, of Brownsburg James A. Schellinger, of Indianapolis Beverly Matthews, of New Castle Lacy M. Johnson, of Indianapolis Sherrianne M. Standley, of Evansville Dustin T. White, of Jeffersonville Katherine L. Davis, of Indianapolis Robin E. Winston, of Indianapolis Freedom Socialist Party (write-in candidates) Pledged to Stephen Durham of New York for President Susan E. Williams, of New York, New York Elizabeth Maloney, of Newark, New Jersey Freedom Socialist Party (write-in candidates) Pledged to Christina Lopez, of Washington for President Doug Barnes, of Seattle, Washington Doreen McGrath, of Seattle, Washington Christopher Smith, of Seattle, Washington Green Party (write-in candidates) Pledged to Jill Stein of Massachusetts for President Andrew Straw, of Goshen Beth Hayes, of Indianapolis Jay Parks, of Indianapolis Jeff Sutter, of South Bend John Loflin, of Indianapolis Kathleen Petitjean, of Mishawaka Kevin McCracken, of Columbus Michael Berndt, of Bloomington Neal Smith, of Indianapolis Pam Raider, of Nashville Sarah Dillon, of Terre Haute Libertarian Party: Pledged to Gary Johnson of New Mexico for President and James P. Gray of California for Vice-President Sam Goldstein, of Indianapolis Brad Klopfenstein, of Indianapolis Chris Spangle, of Greenwood Dan Drexler, of Indianapolis Mike Kole, of Fishers Jerry Titus, of Kokomo Susan Bell, of Hagerstown Paul Morrell, of Arlington Matt Wittlief, of Indianapolis Andy Wolf, of LaPorte Beth Duensing, of St. -

2012 General Election Results

2012 General Election November 6 Official Results Ballots Counted Mailin Ballots Distributed: 137,711 Mailin: 130,252 Total Registered: 248,903 Early Voting: 17,750 Active Voters: 187,962 Polling Place: 32,710 Expected Turnout: 173,890 Total: 180,712 Website last updated: 10:00 AM, Nov. 21, 2012 Complete Results PRESIDENTIAL ELECTORS Votes Percent VIRGIL H GOODE JR / JIM CLYMER AMERICAN CONSTITUTION 262 0.15% BARACK OBAMA / JOE BIDEN DEMOCRATIC 125,091 69.69% MITT ROMNEY / PAUL RYAN REPUBLICAN 49,981 27.84% GARY JOHNSON / JAMES P GRAY LIBERTARIAN 2,794 1.56% JILL STEIN / CHERI HONKALA GREEN 870 0.48% STEWART ALEXANDER / ALEX MENDOZA SOCIALIST USA 16 0.01% ROSS C ROCKY ANDERSON / LUIS J RODRIGUEZ JUSTICE 99 0.06% ROSEANNE BARR / CINDY LEE SHEEHAN PEACE AND FREEDOM 202 0.11% JAMES HARRIS / ALYSON KENNEDY SOCIALIST WORKERS 5 0.00% TOM HOEFLING / JONATHAN D ELLIS AMERICA'S 19 0.01% GLORIA LA RIVA / FILBERTO RAMIREZ JR SOCIALISM AND LIBERATION 9 0.01% MERLIN MILLER / HARRY V BERTRAM AMERICAN THIRD POSITION 16 0.01% JILL REED / TOM CARY UNAFFILIATED 87 0.05% THOMAS ROBERT STEVENS / ALDEN LINK OBJECTIVIST 14 0.01% SHEILA SAMM TITTLE / MATTHEW A TURNER WE THE PEOPLE 22 0.01% JERRY WHITE / PHYLLIS SCHERRER SOCIALIST EQUALITY 12 0.01% RANDALL TERRY / MISSY REILLY SMITH INDEPENDENT / REPUBLICAN 0 0.00% Total Votes: 179,499 REPRESENTATIVE TO THE 113TH UNITED STATES CONGRESS DISTRICT 2 Votes Percent KEVIN LUNDBERG REPUBLICAN 27,623 21.54% JARED POLIS DEMOCRATIC 93,758 73.11% RANDY LUALLIN LIBERTARIAN 3,922 3.06% SUSAN P HALL GREEN 2,934 2.29%