The Chishima—Ravenna Collision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voyager of the Seas®

Voyager of the Seas® From May to October in 2021, Voyager of the Seas® makes its way to Beijing to offer 4-7 night itineraries with stops at culture-rich Kyoto and vibrant Nagasaki. Southeast Asia is home to some of the most exotic shores in the world like temple-rich Malacca in Malaysia, vibrant Bangkok and tropical Phuket in Thailand, and scenic Nha Trang in Vietnam. And from November 2021 to March 2022, Voyager of the Seas® unlocks them all with sailings out of Singapore. Choose from 3 -to 5-night getaways to Penang, Malacca, Kuala Lumpur and Phuket, or opt for longer weeklong wanders with stops in Vietnam and overnights in Bangkok or Phuket —the opportunities for Far East adventures are endless. ITINERARY SAIL DATE PORT OF CALL 4-Night Best of Fukuoka April 30, 2021 Beijing (Tianjin), China • Cruising • May 4, 30, 2021 Fukuoka, Japan • Cruising • Beijing June 8, 2021 (Tianjin), China October 21, 2021 5-Night Fukuoka & Nagasaki May 8, 2021 Beijing (Tianjin), China • Cruising • June 12, 21, 2021 Fukuoka, Japan • Nagasaki, Japan • July 3, 17, 22, 2021 Cruising • Beijing (Tianjin), China August 1, 22, 2021 September 21, 2021 5-Night Shimonoseki & Sasebo May 13, 2021 Beijing (Tianjin), China • Cruising • Shimonoseki, Japan • Sasebo, Japan • Cruising • Beijing (Tianjin), China 5-Night Kumamoto & Nagasaki May 18, 2021 Beijing (Tianjin), China • Cruising • Kumamoto, Japan • Nagasaki, Japan • Cruising • Beijing (Tianjin), China 5-Night Fukuoka & Sasebo June 3, 2021 Beijing (Tianjin), China • Cruising • July 27, 2021 Fukuoka, Japan • Sasebo (Uragashira), October 11, 2021 Japan • Cruising • Beijing (Tianjin), China Book your Asia adventures today! Features vary by ship. -

For Travel Agents SETOUCHI

For Travel Agents SETOUCHI Tokyo JAPAN Kyoto 22 New Experiences Brush Up PROJECT 2018 Videos Information The reflection of ~Re-wind~ You are a Setouchi DMO Setouchi in your eyes vision of beauty at Setouchi Official Homepage To those who are considering traveling to Japan, Please enjoy these videos which illustrate the enchantment of travel to the Setouchi area. For Travel Agents To travel professionals planning for Japan, “Setouchi” is an area that is gaining attention as a new destination location in Japan. Eleven experts have refined and polished hitherto unknown charms of this gemstone of an area, and 22 new travel products have been produced. All of these products designed for foreign tourists visiting Japan have been made for professionals active in the tourism industry. In planning this “brush up” project, the advice and opinions of both domestic and foreign tourism industry professionals, land operators, and tourists from North America and Europe who have experience visiting Japan were taken into consideration. Please make use of this brochure which lays out “Unique Experiences in Setouchi” as new proposals for foreign customers visiting Japan. *The term “Setouchi” refers to the area comprised of the seven prefectures that surround Japan’s Seto Inland Sea. SETOUCHI DMO Chief Operating Officer Katsunori Murahashi 1 2 For Travel Agents Agawa Okayama Hagi Hyogo Tokyo Maneki-Neko Okayama 10 Kyoto Yamaguchi Museum Hiroshima Airport Imbe 3 (Bizen Pottery Village) 2 South Korea 12 Hiroshima (Busan) 4 Hiroshima Sta. 5 Yoshinaga Ruriko-ji Temple Pagoda Airport Okayama Sta. 9 Yamaguchi Miyahama Himeji Castle Onsen Saijo 17 Imbe Shin-Yamaguchi Sta. -

Port of Shimonoseki

Introduction of Destinations for Seto Inland Sea Cruises Based on a survey conducted by the Setouchi Promotion Coordination Council Port of Shimonoseki (No.1 wharf)50,000 tons (Arcaport)50,000 tons Scale of Pier (Choshu Dejima)110,000 tons. From April 2018, 220,000 ton class will be possible Ferry/barge (Ferry) Yes ・ No / (Barge) Yes ・ No 1 Port Summary Shimonoseki City Port and Harbor Bureau Promotion Division General Information (TEL)+81-83-231-1277 (MAIL)[email protected] (URL)http://www.shimonoseki-port.com/e/index.htm (No.1 wharf) walk 10 minutes Transportation & time to central city (Arcaport) Bus 5 minutes areas (Choshu Dejima) Taxi 12 minutes / Bus 30 minutes (No.1 wharf) walk 10 minutes to Shimonoseki Station 2 Secondary Transport (Arcaport)Sanden Transport Kaikyokan mae/1 to 5 minute walk, get on then to Transportation & time to nearest Shimonoseki Station (Choshu Dejima) station Taxi 6 minutes to Hatabu Station Sanden Transport Akada Shogakko Mae / 5 minute walk, then 30 minutes on the bus to Shimonoseki Station (Bus) No. 1 wharf 30 Arcaport 30 ※maximum 10 in the past Parking Choshu Dejima 100 ※maximum 52 in the past (Taxi Pool) Yes ・ No CIQ Acceptance (Customs, Immigration, Quarantine) Can process/General information same as above 3 Procedures at Port /General Information ・Setting up an Information Corner(Tourist Information Office) tourism information, arrange taxis, etc. ・Complimentary shuttle bus ・Set up currency exchange Other facilities, services, etc. ・Set up free Wi-Fi spots when cruise ship anchors(maximum 100 devices) ・Arrange guides for product sales (severala volunteer interpreters) ・Multilingual guide books available (English, Korean, Chinese (traditional/simplified)) ・Kanmon Kaikyo, Castle Town Chofu, Kaikyokan Aquarium, Ganryujima, Tsunoshima ・Kanmon Kaikyo Fireworks Festival, Shimonoseki Kaikyo Festival, Shimonoseki Bakan Festival Main Tourist Spots & Attractions ・Akama Shrine, Karato Market, Kanmon Pedestrian Tunnel ,Mt. -

By Municipality) (As of March 31, 2020)

The fiber optic broadband service coverage rate in Japan as of March 2020 (by municipality) (As of March 31, 2020) Municipal Coverage rate of fiber optic Prefecture Municipality broadband service code for households (%) 11011 Hokkaido Chuo Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11029 Hokkaido Kita Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11037 Hokkaido Higashi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11045 Hokkaido Shiraishi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11053 Hokkaido Toyohira Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11061 Hokkaido Minami Ward, Sapporo City 99.94 11070 Hokkaido Nishi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11088 Hokkaido Atsubetsu Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11096 Hokkaido Teine Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11100 Hokkaido Kiyota Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 12025 Hokkaido Hakodate City 99.62 12033 Hokkaido Otaru City 100.00 12041 Hokkaido Asahikawa City 99.96 12050 Hokkaido Muroran City 100.00 12068 Hokkaido Kushiro City 99.31 12076 Hokkaido Obihiro City 99.47 12084 Hokkaido Kitami City 98.84 12092 Hokkaido Yubari City 90.24 12106 Hokkaido Iwamizawa City 93.24 12114 Hokkaido Abashiri City 97.29 12122 Hokkaido Rumoi City 97.57 12131 Hokkaido Tomakomai City 100.00 12149 Hokkaido Wakkanai City 99.99 12157 Hokkaido Bibai City 97.86 12165 Hokkaido Ashibetsu City 91.41 12173 Hokkaido Ebetsu City 100.00 12181 Hokkaido Akabira City 97.97 12190 Hokkaido Monbetsu City 94.60 12203 Hokkaido Shibetsu City 90.22 12211 Hokkaido Nayoro City 95.76 12220 Hokkaido Mikasa City 97.08 12238 Hokkaido Nemuro City 100.00 12246 Hokkaido Chitose City 99.32 12254 Hokkaido Takikawa City 100.00 12262 Hokkaido Sunagawa City 99.13 -

CV in English

Sarah Brayer sarahbrayer.com [email protected] ________________ born: Rochester, New York lives: Kyoto, Japan and New York since 1980 Solo Exhibitions 2019 Indra’s Cosmic Net, Daitokuji Studio, Kyoto 2018 Kyoto Passages, The Ren Brown Collection, Bodega Bay, California The Red Thread, Daitokuji Studio, Kyoto 2016 Celestial Threads, Daitokuji Studio, Kyoto ArtHamptons, The Tolman Collection: New York 2015 Luminosity, Hanga Ten, London, England Luminosity, Daitokuji Studio, Kyoto 2014 Between Two Worlds: Poured Paperworks by Sarah Brayer, Castellani Art Museum, Niagara University. catalog In the Moment, Gallery Bonten, Shimonoseki, Japan 2013 Tiger’s Eye, The Verne Collection, Cleveland, Ohio Cloud Garden Paperworks, The Ren Brown Collection, Bodega Bay, California 2012 Luminosity: Night Paperworks, Reike Studio, Santa Fe, New Mexico Light and Energy, Gallery Bonten, Shimonoseki, Japan Recent Works by Sarah Brayer, The Tolman Collection: New York 2011 East Meets West, The Tolman Collection, New York, NY New Works in Washi & Glass, Gallery Shinmonzen, Kyoto The Schoolhouse Gallery, Mutianyu, Beijing, China Gallery Bonten, Shimonoseki, Japan 2010 Luminosity: Night Paperworks, Kamigamo Studio, Kyoto Mythos, The Ren Brown Collection, Bodega Bay, California Art in June, Rochester, New York 30 Years of Art in Kyoto: Sarah Brayer Studio, Kyoto 2007 The Ren Brown Collection, Bodega Bay Gallery Bonten, Shimonoseki, Japan Round the Horn, Nantucket Art in June, Rochester, New York 2006 Whisper to the Moon, Iwakura Kukan, Kyoto Art in June, Rochester, -

The Korean War and Japanese Ports: Support for the UN Forces and Its Influences

The Korean War and Japanese Ports: Support for the UN Forces and Its Influences ISHIMARU Yasuzo Introduction When the Korean War broke out on June 25, 1950, Japan had been under the occupation of the Allied Forces. Nevertheless, Japan achieved its role as a rear base for the supply and transit of soldiers and materials. What linked the Korean Peninsula—the battlefield—and Japan—the rear base—were the sea and air transport routes, and what supported the sea transport routes were the Japanese ports. These ports in fact constituted important hubs connecting the battlefield and the rear base. During the same period, new laws pertaining to ports were established. These were the Port and Harbor Law (Law No. 218 of 1950) and the Old Naval Base City Conversion Law (Law No. 220 of 1950). The Port and Harbor Law established on the principle that the ports should be managed by local administration.1 Meanwhile, the aim of the Old Naval Base City Conversion Law was to establish a peaceful Japan by converting the former naval bases2 into industrial port cities. Therefore, right when Japanese ports were changing to new ports, the nation was thrown into the Korean War, which set back their efforts. The Korean War had a decisive influence on the path of post-war Japan,3 which prompted studies on its political and economic influences, its history, and on the rearmament of Japan. However, although some literature exists on Japan’s support to the Korean War,4 no studies have ever tried to focus on ports. This article discusses the role Japanese ports played during the Korean War and how they were affected by the war. -

Comfort Women" Case: Judgment of April 27, 1998, Shimonoseki Branch, Yamaguchi Prefectural Court, Japan

Washington International Law Journal Volume 8 Number 1 1-1-1999 The "Comfort Women" Case: Judgment of April 27, 1998, Shimonoseki Branch, Yamaguchi Prefectural Court, Japan Taihei Okada Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wilj Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Law and Gender Commons Recommended Citation Taihei Okada, Translation, The "Comfort Women" Case: Judgment of April 27, 1998, Shimonoseki Branch, Yamaguchi Prefectural Court, Japan, 8 Pac. Rim L & Pol'y J. 63 (1999). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wilj/vol8/iss1/13 This Translation is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at UW Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington International Law Journal by an authorized editor of UW Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright 0 1999 Pacific Rim Law & Policy Association THE "COMFORT WOMEN" CASE: JUDGMENT OF APRIL 27, 1998, SHIMONOSEKI BRANCH, YAMAGUCHI PREFECTURAL COURT, JAPANt Translated by Taihei Okada$ Abstract: The Court found in favor of three Korean "Comfort Women" plaintiffs awarding monetary damages from the Defendant Japan for failure to pass legislation redressing the acknowledged harm caused to the "Comfort Women." The Court dismissed demands for an official apology and the claims of forced female laborers. JUDGMENT' 2 This court hereby issues the following judgment on the Plaintiffs' 3 claim for an official apology and compensation for "Comfort Women and female Teishintai forced laborers from the city of Pusan, and an official apology and compensation for all female Teishintai forced laborers and "Comfort Women," based on proceedings in this court concluding September 29, 1997. -

Shimonoseki Port Tourist Information

Shimonoseki Port Tourist Information http://www.mlit.go.jp/kankocho/cruise/ Karato Market The Karato Market carries fresh fish that is the pride of strait town Shimonoseki. On weekends and holidays, the shops hold an event called "Iki-ikiBakangai" in which they engage in a sushi battle and show off their skills making globefish sushi and other items, including catch-of-the-day sushi and "donburi." At the Kamon Wharf commercial complex next door, you can enjoy globefish dishes at prices you'll only find there. Location/View 750-0005 10min via car from main port(3km) Access 10min walk from Arcaport Berth Every Friday, Saturday and Sunday, Parking for 40buses Season National Holiday tour buses Related links Contact Us[Shimonoseki City Tourism Policy Division] TEL:083-231-1350 l E-MAIL:[email protected] Website: https://shimonoseki.travel/english/index.html Globefishes(globefish dishes; Fugu dishes) It's said that the season for globefish dishes is from autumn equinox to spring equinox, but today the dishes can be enjoyed year round. Be sure to try authentic globefish dishes. The first of these that comes to mind is "fukusashi," which is arranged on the plate like a beautiful flower. Also called "kiku-mori" in reference to its chrysanthemum ("kiku") appearance, it's a famous globefish dish. Location/View Access Season Year-round Related links Contact Us[Shimonoseki City Tourism Policy Division] TEL:083-231-9653 l E-MAIL:[email protected] Website: https://shimonoseki.travel/english/index.html Kawara-soba This is a specialty dish of KawatanaOnsen. -

Shimonoseki: a Town with a 1000 Year-Old History

Shimonoseki: a town with a 1000 year-old history Shimonoseki, situated on the westernmost end of the mainland of Japan has prospered as a gateway to Eurasia as well as a strategic stop for land and sea transport in the area. The town, boasting attractive scenery along the Kanmon Strait, has witnessed so many important events in Japan’s history that it forms an integral part of its culture. As the location of a famous naval battle in the War between the Genji and the Heike clans in 1185, Shimonoseki played a key role in the transition from aristocratic to warrior rule in Japan. The city has places of natural beauty and historical interest typical of a castle town, such as ancient samurai residences and clay walls. Visitors will enjoy the distinctively Japanese atmosphere they exude. With its wealth of historical sites, ethnic ambience, beautiful scenery and Japanese food, Shimonoseki is a town that will capture your heart. Shimonoseki Japan to Nagato City 276 TSUKUNO Natural scenic attractions HOT SPRING TSUNOSHIMA ISLAND 275 ICHINOMATA HOT SPRING HistoryHof Shimonoseki TOYOTA LAKE 800 years ago the great “Genji” and “Heike” clans fought a decisive JR San-in Main Line battle (the so-called Genji and Heike War in Dannoura) at “Dannoura” HIBIKINADA in Shimonoseki City. Of note are also the Akama Shrine dedicated to Kanmon Strait the 8-year old Emperor Antoku who sacrificed his life after his clan’s FUTAOIJIMA Tsunoshima Island ISLAND defeat in this war, “Ganryujima Island” where two samurais (Miyamoto Musashi and Sasaki Kojiro) clashed swords for the no.1 position in SHIMONOSEKI CITY The Kanmon Walker Shimonoseki is surrounded to the south by Seto Japan 400 years ago, and the numerous footsteps of patriots who to Yoshimi Submarine Tunnel Inland Sea National Park and to the north by Kita- fought for construction of modern Japan under the Meiji Restoration. -

Supplementary Information to Financial Results

J. Front Retailing Supplementary Information to Financial Results I. J. Front Retailing Consolidated Statements 【IFRS】 1. Consolidated business performance (Millions of yen, %) Three months YoY Three months Item ended ended May 31, 2020 May 31, 2019 Amount % 1. Gross sales 113,438 (160,564) (58.6) 274,002 2. Revenue 63,459 (49,023) (43.6) 112,482 3. Gross profit 21,272 (30,895) (59.2) 52,167 4. Gross margin 33.52 % Difference (12.86) % 46.38 % Selling, general and administrative expenses 5. 25,152 (14,539) (36.6) 39,691 (SGA) 6. Business profit (3,879) (16,355) - 12,476 7. Operating profit (27,103) (39,897) - 12,794 8. Profit before tax (28,492) (40,642) - 12,150 Profit attributable to owners of 9. (20,334) (27,781) - 7,447 parent 10. Total assets 1,281,163 40,855 1,240,308 [Of which: right-of-use assets] [194,189] [(8,327)] [202,516] 11. Equity attributable to owners of parent 362,262 (24,926) 387,188 Ratio of equity attributable to owners of 12. 28.3 % Difference (2.9) % 31.2 % parent to total assets 13. Interest-bearing debt 602,093 123,320 478,773 [Of which: lease liabilities] [215,609] [(4,888)] [220,497] Notes: 1. Gross sales are calculated by converting sales from purchase recorded at the time of sale (shoka shiire ) of the "Department Store Business" and "Other (Daimaru Kogyo)," which are recognized as revenue under IFRS, into gross amount and converting the net amount of sales of the "Parco Business" into tenant transaction volume (gross amount basis). -

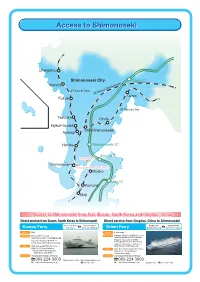

Access to Shimonoseki

AccessAccess toto ShimonosekiShimonoseki Umegatou Shimonoseki City Ozuki IC Yoshimi JR San-in Line JR Sanyo Shinkansen Ozuki Fukue JR Sanyo Line Yasuoka Chofu Kajikuri-Godaich Shin-Shimonoseki Ayaragi Hatabu Shimonoseki IC Mojiko IC Karato Market Shimonoseki Shimonoseki International Terminal Mojiko Moji IC Komorie Moji Access to Shimonoseki from Asia ((Busan, South Korea and Qingdao, China)) Direct service from Busan, South Korea to Shimonoseki Direct service from Qingdao, China to Shimonoseki Busan, South Korea Shimonoseki port Qingdao, China Shimonoseki port Kampu Ferry (Busan port) (International Terminal) Orient Ferry (Qingdao port Terminal) (International Terminal) Service Daily Service 2 days/ week Ferry Schedule Departure: Busan 21:00 → Ferry Schedule Departure: Qingdao 22:00/Mon.& Thu.→ Arrival: Shimonoseki 7:45 following morning Arrival: Shimonoseki 8:30/2 days later Departure: Shimonoseki 12:00/Wed.→ Departure: Shimonoseki 19:45 → Arrival: Qingdao 16:00/2 the next day Arrival: Busan 8:00 following morning Departure: Shimonoseki 17:00/Sat.→ Prices Adult, One-way ¥9,000 (2nd class ~) Arrival: Qingdao 8:00/2 days later Child (6 to 12 Years) Half price Prices Adult, One-way ¥15,000 (2nd B class~) ※Terminal Service Charge extra Child (6 to 11 Years) Half price (Adult: ¥610; Child: ¥300 ) ※Discount available Information Shimonoseki International Terminal Information Shimonoseki International Terminal Pukwan Ferry Co.,Ltd. http://www.pukwan.co.kr/ URL http://www.kampuferry.co.jp/ 051-463-3161 URL http://www.orientferry.co.jp/ Qingdao office 0532-83871160 GuideGuide forfor accessingaccessing ShimonosekiShimonoseki transittransit Ferry from Moji port Kanmon Kaikyo [Channel] connecting ferry Moji port Karato Service Daily Prices Adult: One-way ¥400 Child (Primary School): ¥200 Duration 5 minutes Information Information: Kanmon-kisen Co., Ltd. -

A Hundred Years of Technology and Product Development at Kobe Steel Dr

(Keynote article) A Hundred Years of Technology and Product Development at Kobe Steel Dr. Hiroshi SATOH Executive Vice President Head of Technical Development Group For 100 years, ever since its foundation in 1905, quality requirements. The Casting and Forging Kobe Steel has been one of the world's leaders in Division grew continuously and built up, through the development and commercialization of new in-house development and acquisition, technologies and products. As well as continuing technologies to produce the world's largest the development of the technologies and products propellers at that time for supertankers. In 1976 featured in its original business, the company we introduced an 8000t forging press, one of the quickly extended its scope into totally new world's largest, and since then have led the world technologies and products leading to new business in the area of large-size cast and forged steel opportunities. products with high reliability. In 1905, it was National Policy to grow the Steel In 1959 the Kobe Works achieved a major and Heavy Industries in Japan. In this social milestone with the 'blowing-in' of its No.1 blast climate Kobe Steel started to manufacture steel and furnace, and we made the first step from an open- industrial machinery as its first steps as a material hearth manufacturer toward an integrated, blast and machinery company. The technical and furnace, steel manufacturer. Now, the Kobe Works commercial synergies produced by these separate is one of the world's largest plants specialized in undertakings in the material and machinery fields the production of wire and rods, and produces created opportunities for new products, which over high-quality, high-strength wires used for the years have grown into Kobe Steel's current, automotive valve-springs, suspension springs, diversified, business.