First Evaluation of the Population Structure, Genetic Diversity and Landscape Connectivity of the Endangered Arabian Tahr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arabian Ungulate CAMP & Leopard, Tahr, and Oryx PHVA Final Report 2001.Pdf

Conservation Assessment and Management Plan (CAMP) For The Arabian Ungulates and Leopard & Population and Habitat Viability Assessment (PHVA) For the Arabian Leopard, Tahr, and Arabian Oryx 1 © Copyright 2001 by CBSG. A contribution of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group. Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (SSC/IUCN). 2001. Conservation Assessment and Management Plan for the Arabian Leopard and Arabian Ungulates with Population and Habitat Viability Assessments for the Arabian Leopard, Arabian Oryx, and Tahr Reports. CBSG, Apple Valley, MN. USA. Additional copies of Conservation Assessment and Management Plan for the Arabian Leopard and Arabian Ungulates with Population and Habitat Viability Assessments for the Arabian Leopard, Arabian Oryx, and Tahr Reports can be ordered through the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124. USA. 2 Donor 3 4 Conservation Assessment and Management Plan (CAMP) For The Arabian Ungulates and Leopard & Population and Habitat Viability Assessment (PHVA) For the Arabian Leopard, Tahr, and Arabian Oryx TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1: Executive Summary 5. SECTION 2: Arabian Gazelles Reports 18. SECTION 3: Tahr and Ibex Reports 28. SECTION 4: Arabian Oryx Reports 41. SECTION 5: Arabian Leopard Reports 56. SECTION 6: New IUCN Red List Categories & Criteria; Taxon Data Sheet; and CBSG Workshop Process. 66. SECTION 7: List of Participants 116. 5 6 Conservation Assessment and Management Plan (CAMP) For The Arabian Ungulates and Leopard & Population and Habitat Viability Assessment (PHVA) For the Arabian Leopard, Tahr, and Arabian Oryx SECTION 1 Executive Summary 7 8 Executive Summary The ungulates of the Arabian peninsula region - Arabian Oryx, Arabian tahr, ibex, and the gazelles - generally are poorly known among local communities and the general public. -

Arabian Tahr in Oman Paul Munton

Arabian Tahr in Oman Paul Munton Arabian tahr are confined to Oman, with a population of under 2000. Unlike other tahr species, which depend on grass, Arabian tahr require also fruits, seeds and young shoots. The areas where these can be found in this arid country are on certain north-facing mountain slopes with a higher rainfall, and it is there that reserves to protect this tahr must be made. The author spent two years in Oman studying the tahr. The Arabian tahr Hemitragus jayakari today survives only in the mountains of northern Oman. A goat-like animal, it is one of only three surviving species of a once widespread genus; the other two are the Himalayan and Nilgiri tahrs, H. jemlahicus and H. hylocrius. In recent years the government of the Sultanate of Oman has shown great interest in the country's wildlife, and much conservation work has been done. From April 1976 to April 1978 I was engaged jointly by the Government, WWF and IUCN on a field study of the tahr's ecology, and in January 1979 made recommendations for its conservation, which were presented to the Government. Arabian tahr differ from the other tahrs in that they feed selectively on fruits, seeds and young shoots as well as grass. Their optimum habitat is found on the north-facing slopes of the higher mountain ranges of northern Oman, where they use all altitudes between sea level and 2000 metres. But they prefer the zone between 1000 and 1800m where the vegetation is especially diverse, due to the special climate of these north-facing slopes, with their higher rainfall, cooler temperatures, and greater shelter from the sun than in the drought conditions that are otherwise typical of this arid zone. -

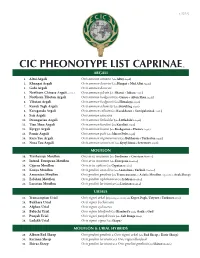

Cic Pheonotype List Caprinae©

v. 5.25.12 CIC PHEONOTYPE LIST CAPRINAE © ARGALI 1. Altai Argali Ovis ammon ammon (aka Altay Argali) 2. Khangai Argali Ovis ammon darwini (aka Hangai & Mid Altai Argali) 3. Gobi Argali Ovis ammon darwini 4. Northern Chinese Argali - extinct Ovis ammon jubata (aka Shansi & Jubata Argali) 5. Northern Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Gansu & Altun Shan Argali) 6. Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Himalaya Argali) 7. Kuruk Tagh Argali Ovis ammon adametzi (aka Kuruktag Argali) 8. Karaganda Argali Ovis ammon collium (aka Kazakhstan & Semipalatinsk Argali) 9. Sair Argali Ovis ammon sairensis 10. Dzungarian Argali Ovis ammon littledalei (aka Littledale’s Argali) 11. Tian Shan Argali Ovis ammon karelini (aka Karelini Argali) 12. Kyrgyz Argali Ovis ammon humei (aka Kashgarian & Hume’s Argali) 13. Pamir Argali Ovis ammon polii (aka Marco Polo Argali) 14. Kara Tau Argali Ovis ammon nigrimontana (aka Bukharan & Turkestan Argali) 15. Nura Tau Argali Ovis ammon severtzovi (aka Kyzyl Kum & Severtzov Argali) MOUFLON 16. Tyrrhenian Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka Sardinian & Corsican Mouflon) 17. Introd. European Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka European Mouflon) 18. Cyprus Mouflon Ovis aries ophion (aka Cyprian Mouflon) 19. Konya Mouflon Ovis gmelini anatolica (aka Anatolian & Turkish Mouflon) 20. Armenian Mouflon Ovis gmelini gmelinii (aka Transcaucasus or Asiatic Mouflon, regionally as Arak Sheep) 21. Esfahan Mouflon Ovis gmelini isphahanica (aka Isfahan Mouflon) 22. Larestan Mouflon Ovis gmelini laristanica (aka Laristan Mouflon) URIALS 23. Transcaspian Urial Ovis vignei arkal (Depending on locality aka Kopet Dagh, Ustyurt & Turkmen Urial) 24. Bukhara Urial Ovis vignei bocharensis 25. Afghan Urial Ovis vignei cycloceros 26. -

Conservation Introduction of the Arabian Tahr to Sir Bani Yas Island, Abu Dhabi Emirate

Evidence-based practice Conservation introduction of the Arabian Tahr to Sir Bani Yas Island, Abu Dhabi Emirate, UAE: challenges and lessons learnt Shaikha Al Dhaheri1, Pritpal S. Soorae1, Meyer de Kock2, Abid Mehmood3, Andries Gouws3, Kate Burns2, Malik Rapaie3, Ibrahim Al Nassan3, John Cole4, Hamad Al Zoywed4, Rashid Al Zaabi1 1Environment Agency-ABU DHABI, United Arab Emirates 2Al Bustan Zoological Center, Al Dhaid, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates 3Barari Forest Management, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates 4Tourism Development & Investment Company, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates Correspondence: Pritpal Singh Soorae; [email protected] JZAR Evidence-based practice Evidence-based JZAR Keywords: Abstract Arabian tahr, conservation introduction, The Arabian tahr (Arabitragus jayakari) is a mountain ungulate endemic to the Arabian Peninsula and Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, Sir found only along the Hajar Mountain range that extends between the United Arab Emirates (UAE) Bani Yas Island and the Sultanate of Oman. In the UAE, the Arabian tahr was known to be present in two locations, namely Wadi Wurayah in Fujairah Emirate and Jebel Hafeet in Abu Dhabi Emirate, but no sightings Article history: have been recorded from Wadi Wurayah since 2013. A conservation introduction project was initiated Received: 19 November 2016 to create a population of semi-wild Arabian tahr that would be better suited for reintroduction into Accepted: 18 April 2017 their historic range. The population on Sir Bani Yas Island in the Arabian Gulf in Abu Dhabi Emirate has Published online: 31 July 2017 generated many challenges and lessons learnt as an individual were lost to predation and another to injury. -

'Arabian Ark' Helps Save Wildlife from Extinction 4 February 2015, by Wissam Keyrouz

'Arabian Ark' helps save wildlife from extinction 4 February 2015, by Wissam Keyrouz started bringing animals to Sir Bani Yas in 1971. "He started developing the island into a nature reserve and the idea back then was to create an Arabian Ark for his people," said Marius Prinsloo, general manager of operations at the island. "We have been successful," he said of the conservation efforts. 'Great results' Sir Bani Yas is now home to about 500 Arabian Oryx—one of the world's largest herds. A falcon takes off on Sir Bani Yas Island, one of the Sameer Ghani, an independent conservation largest natural islands in the UAE specialist, said the reserve's Arabian Oryx breeding programme was showing "great results" after the animal "went extinct in the wild in the early 1970s". Oryx, giraffes and cheetahs roam an "Arabian Ark" A type of antelope, they once roamed most of the nature reserve on a desert Gulf island where Arabian Peninsula but rampant hunting meant that species once facing extinction in the region are for years they survived only in captivity. making a comeback. Since animals were first brought to Sir Bani Yas off the coast of Abu Dhabi more than four decades ago, their total population has soared to more than 13,000. Twenty-five species of mammals and 170 types of birds are found in a nature reserve covering an area of 1,400 hectares (3,500 acres). They include striped hyenas, caracals—also known as the desert lynx—and the Arabian tahr, a small goat-like mammal indigenous to the Hajar Mountains between the UAE and Oman. -

Status and Ecology of the Nilgiri Tahr in the Mukurthi National Park, South India

Status and Ecology of the Nilgiri Tahr in the Mukurthi National Park, South India by Stephen Sumithran Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Fisheries and Wildlife Sciences APPROVED James D. Fraser, Chairman Robert H. Giles, Jr. Patrick F. Scanlon Dean F. Stauffer Randolph H. Wynne Brian R. Murphy, Department Head July 1997 Blacksburg, Virginia Status and Ecology of the Nilgiri Tahr in the Mukurthi National Park, South India by Stephen Sumithran James D. Fraser, Chairman Fisheries and Wildlife Sciences (ABSTRACT) The Nilgiri tahr (Hemitragus hylocrius) is an endangered mountain ungulate endemic to the Western Ghats in South India. I studied the status and ecology of the Nilgiri tahr in the Mukurthi National Park, from January 1993 to December 1995. To determine the status of this tahr population, I conducted foot surveys, total counts, and a three-day census and estimated that this population contained about 150 tahr. Tahr were more numerous in the north sector than the south sector of the park. Age-specific mortality rates in this population were higher than in other tahr populations. I conducted deterministic computer simulations to determine the persistence of this population. I estimated that under current conditions, this population will persist for 22 years. When the adult mortality was reduced from 0.40 to 0.17, the modeled population persisted for more than 200 years. Tahr used grasslands that were close to cliffs (p <0.0001), far from roads (p <0.0001), far from shola forests (p <0.01), and far from commercial forestry plantations (p <0.001). -

ACE Appendix

CBP and Trade Automated Interface Requirements Appendix: PGA August 13, 2021 Pub # 0875-0419 Contents Table of Changes .................................................................................................................................................... 4 PG01 – Agency Program Codes ........................................................................................................................... 18 PG01 – Government Agency Processing Codes ................................................................................................... 22 PG01 – Electronic Image Submitted Codes .......................................................................................................... 26 PG01 – Globally Unique Product Identification Code Qualifiers ........................................................................ 26 PG01 – Correction Indicators* ............................................................................................................................. 26 PG02 – Product Code Qualifiers ........................................................................................................................... 28 PG04 – Units of Measure ...................................................................................................................................... 30 PG05 – Scientific Species Code ........................................................................................................................... 31 PG05 – FWS Wildlife Description Codes ........................................................................................................... -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced from the Microfilm Master

The takin and muskox: A molecular and ecological evaluation of relationship Item Type Thesis Authors Groves, Pamela Download date 01/10/2021 15:20:15 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/9423 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. Hie quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margin^ and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. » Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sectionssmall overlaps.with Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Native Plants of United Arab Emirates

FACTS OF UAE TITLE- FACTS OF UAE 1 NATIVE PLANTS OF THE UAE Cornulaca monacantha – In Arabic it is known as had and djouri is a straggling, branched, woody shrub growing to a height of 60 centimeters (24 in). It is a desert plant found in the Middle East and the Sahara Desert hyacinth (Cistanche tubulosa) – Branchless parasite fleshy herb, up to 1m high with erect whitish single stem, simple and up to 4cm thick, stem arise from tuber. Common in coastal areas of the Arabian Gulf coast and on inland saline sand plains. NATIVE PLANTS 2 NATIVE PLANTS OF THE UAE Arfaj (Rhanterium epapposum) – Once a common dwarf shrub in many north-eastern parts of UAE, overgrazing has led to the disappearance of the species in many locations.- Ausaj (Lycium shawii) – Desert plant, common in the UAE in variety of habitats: gravel plains, hillsides, wadis and plantation. Safrawi (Dipterygium glaucum) – Perennial shrub but often flowering and fruiting in the first year. Very common in the UAE, along the Arabian gulf coast, often very close to beach lines, also on saline sand inland, except for the southern part of Abu Dhabi emirate. NATIVE PLANTS 3 NATIVE ANIMALS OF THE UAE Oryx leucoryx (Al maha, al baqr, al barra) – The Arabian Oryx is uniform white, while the flank stripe is absent . Arabian Oryx once occurred over all or most of the plains and deserts of the Arabian Peninsula. Arabian Red Fox (Al taleb al ahmer)- Is similar in color to the common Red Fox. Found throughout the UAE and can adapt to all habitats, from desert to mountains, as well as the urban environment. -

Annual Report 2020 Annual Report 2020

Annual Report 2020 Annual Report 2020 WELCOME TO THE FIRST ANNUAL REPORT Contents Then enter Covid 19, shortly followed by the whole OF THE TAHR FOUNDATION. country going into lock down. The programmed Presidents Report 3 meeting of the TLIG for March was postponed and e have put together a brief report of Minutes 6 then canceled. the activities of the Foundation since Incorporated Financial Statements 8 The Department prioritised their Covid 19 response our last AGM September 2019. The Tahr Jams 11 ahead of everything else at that stage and rightly so W We hope you find our report Duke of Bedford Award 12 but that meant no progress on tahr issues and the Tahr informative; we want to be open and transparent about Give A Little 14 Foundation had no say in how any of that unfolded. the activities of the Tahr Foundation and encourage you Tahr Wars: Part 1 15 When the lockdown was finally lifted Doc seemed in to take the time to read through the report. NZDA’s Tahr Control Operational Plan Submission 19 a rush to get us back around the table and to start the We have had to rise to some big challenges this year, we NZPHGA DoC Tahr Control Operational Plan Submission 23 process of finalising a plan for tahr control for 20/20. have done that and met them head on. Operational Tahr Plan NZTF Submission 27 We were concerned that this renewed haste could We haven’t always achieved all that we would have Safari Club International (NZ) Submission 31 force us into a process that would produce a rushed wanted to, but we have always done our up most to New Zealand Association of Game Estates DOC 37 ill-conceived plan. -

OMAN 1 Month (December 2019 /January 2020) Arabian Tahr It Was

OMAN 1 month (December 2019 /January 2020) Arabian Tahr It was my fourth trip in Oman and as always I have enjoyed: nice people, wonderful scenery, ease to travel independently and of course good wildlife. As always the birding was excellent, but mammalwatching was exceptional with such species as Arabian Tahr, Caracal, Honey Badger, Arabian Wolf, Striped Hyena and Blanford’s Fox. I spent my first night in the north at Wadi Al Muyaidin where I found a Blandford’s Fox during my last trip and again I saw it at the same place, but it was extremely shy this time. Then I drove to Muntasar, a kind of oasis in the center of Oman: I saw several Desert Red Fox and an Arabian Gerboa, plus a few footprints of gazelles. The following night I slept near Qitbit a place quite close where Rüppel’s Fox has been said common. I saw only Desert Red Fox. During my full trip I never saw any Rüppel’s Fox, but everywhere Desert Red Fox (a lot of them have black underparts, from the the neck to the tail). Desert Red Fox are very different from their counterparts from Europe or elsewhere(slimmer, paler with larger ears) and what I think also confusing is the size of Rüppel’s Fox. Rüppel’s Fox are said to be smaller than Red Fox and all of those I have seen in Western Sahara were smaller(see for example the Handbook of Mammals of the world). By the contrary they are said to have the same size of Red Fox in Mammals of Europe, Northern Africa and the Middle East. -

Animals Native to the Arab World

Animals Native to Syrian Hamster The Syrian hamster’s natural habitat is limited to the arid regions of northern Syria and parts of southern Turkey. In the Arab World the local Syrian dialect, these hamsters are nicknamed abū jarāb) because of / ﺟﺮاب أﺑﻮ) ”The Arab world is home to a variety of indigenous “Mister Saddlebags their ability to store food in their cheeks. animals, many of which are unique due to their resilience to harsh weather conditions. They not only inhabit the region, but also serve as symbols of cultural and historical heritage. This graphic feature nine animals native to the Arab world. Algerian Nuthatch The Algerian nuthatch was discovered in 1975 and is the only bird species endemic to Algeria. It nests mostly in Atlas cedar, Algerian fir or oaks. It is currently classified as an endangered species with a small Arabian Horse overall population size in decline. The Arabian horse is one of the oldest horse breeds in the world and today, their bloodline can be traced in most breeds of riding horses. Arabian are an emblem of pride throughout the Arab world, even playing a role in the founding of Qatar. Today the site of the pivotal Barbary Macaque battle Al Shaqab, located on the grounds of Qatar Foundation’s Education City, is an Arabian breeding This species of macaque is found mainly farm and equestrian center commemorating the role of in the Atlas and Rif Mountains of Algeria the Arabian steed in Qatar's independence. and Morocco with a small population living in Gibraltar. Arabian Mau Originally thought to be a random street cat, the Arabian Mau is a descendant of wild Hamadryas Baboon desert cats, making them well suited for hot and arid climates.