To Serve Man? Rod Serling and Effective Destining

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Season 5 Article

N.B. IT IS RECOMMENDED THAT THE READER USE 2-PAGE VIEW (BOOK FORMAT WITH SCROLLING ENABLED) IN ACROBAT READER OR BROWSER. “EVEN’ING IT OUT – A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE LAST TWO YEARS OF “THE TWILIGHT ZONE” Television Series (minus ‘THE’)” A Study in Three Parts by Andrew Ramage © 2019, The Twilight Zone Museum. All rights reserved. Preface With some hesitation at CBS, Cayuga Productions continued Twilight Zone for what would be its last season, with a thirty-six episode pipeline – a larger count than had been seen since its first year. Producer Bert Granet, who began producing in the previous season, was soon replaced by William Froug as he moved on to other projects. The fifth season has always been considered the weakest and, as one reviewer stated, “undisputably the worst.” Harsh criticism. The lopsidedness of Seasons 4 and 5 – with a smattering of episodes that egregiously deviated from the TZ mold, made for a series much-changed from the one everyone had come to know. A possible reason for this was an abundance of rather disdainful or at least less-likeable characters. Most were simply too hard to warm up to, or at the very least, identify with. But it wasn’t just TZ that was changing. Television was no longer as new a medium. “It was a period of great ferment,” said George Clayton Johnson. By 1963, the idyllic world of the 1950s was disappearing by the day. More grittily realistic and reality-based TV shows were imminent, as per the viewing audience’s demand and it was only a matter of time before the curtain came down on the kinds of shows everyone grew to love in the 50s. -

Newsletter — Summer 2016

Newsletter — Summer 2016 Since the mid-1980's this organization has been working to honor Rod Serling—one of the most talented and prolific writers in American television. This newsletter highlights the continuing interest in Rod Serling and his work—in an at- tempt to provide RSMF members with information from the press... on bookshelves... DVDs and the internet. RSMF BOARD MEMBERS TO PRESENT AT ROBERSON SCIENCE FICTION CONVENTION The Rod Serling Memorial Foundation is sponsoring an author’s panel at the 2016 Robercon on Saturday, September 24. Featured panelist are Anne Serling — author of As I Knew Him: My Dad, Rod Serling... Tony Albarella — author of As Timeless As Infinity: The Complete Twilight Zone Scripts of Rod Serling... Amy Boyle Johnston — author of Unknown Serling: An Episodic History Vol. 1... and Nicholas Parisi — au- thor of Dimensions of Imagination: A Journey Through the Life, Work and Mind of Rod Serling. The diversity of the panel will allow us to examine all aspects of Rod Serling’s life and career. This is a great chance to meet these authors in person. Presentations by each author will begin at 2 p.m. — followed by a question and an- swer period afterward. Books will be available for sale and the authors will be signing copies. Robercon is held at the Roberson Museum, 30 Front Street in Rod’s hometown of Binghamton, NY. Hope to see you there! MYSTERY IMAGES Can you identify which pro- duction of a Serling script the images above came NEW ANTHOLOGY from? The member with the MAGAZINE... most correct answers will A new anthology appears in your pe- receive a “ROD SERLING ripheral vision: “Another Dimension.” It MEMORIAL FOUNDATION T brings tales of the macabre, the mysteri- -SHIRT.” E-mail your an- ous, and the just-plain-strange—on paper swers — listing the titles by and in digital versions. -

Enter the Zone...THE TWILIGHT ZONE West Endicott Park Ross Park (Closed for Summer 2020) Recreation Park Highland Park George W

Enter the zone...THE TWILIGHT ZONE West Endicott Park West Park Ross Recreation Park Highland Park Johnson Park George W. CF Johnson Park “Everyone has to have a hometown... (Closed for Summer 2020) Binghamton’s Mine” -Rod Serling Rod Serling (1924-1975) Enter the SERLING zone (Limited Hours for Summer 2020) Binghamton Native, Writer, Producer, Teacher Rod Serling (1924-1975) graduated from Known primarily for his role as the host of Binghamton Central HS, Class of 1943. Now television’s The Twilight Zone, Rod Serling known as Binghamton High School, it is the had one of the most exceptional and varied home of the Rod Serling School of Fine Arts. careers in television. As a writer, a producer, Visit the plaque dedicated to Serling on the and for many years a teacher, Serling constantly front lawn, see the door casing where he signed challenged the medium of television to reach for his name in 1943 while working backstage, visit loftier artistic goals. the Helen Foley Theatre named after Rod’s drama After a brief career in radio, Serling entered television in 1951, penning teacher and mentor and where he was commencement speaker in 1968, scripts for several programs including Hallmark Hall of Fame and leaf through his high school yearbook at the library, or just stroll through Playhouse 90, at a time when the medium was referred to as “The the halls that Rod passed through each school day. Appointments are Golden Age.” suggested. Please contact Lawrence Kassan, Coordinator of Special Events In 1955, Kraft Television Theatre presented Serling’s teleplay Patterns and Theatre for the Binghamton City School District at (607) 762-8202. -

Star Wars © 2012 Lucasfilm Ltd

Star Wars © 2012 Lucasfilm Ltd. & ™. All 0 3 No.55 $ 8 . 9 5 A pril 201 2 1 82658 27762 8 LICENSED COMICS ISSUE: THE RETRO COMICS EXPERIENCE! and an interview with Carol Zone” wife Serling, creator of Rod “Twilight Serling STAR WARS Indiana Jones • Edgar Rice Burroughs—Beyond Tarzan at Dark Horse Comics! • Man from Atlantis Volume 1, Number 55 April 2012 Celebrating the Best The Retro Comics Experience! Comics of the '70s, '80s, '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich J. Fowlks COVER ARTIST Brian Koschack COVER COLORIST Dan Jackson COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Scott Allie Karl Kesel Kevin J. Anderson Dave Land BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 Michael Aushenker Rick Leonardi FLASHBACK: Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Weird Worlds . .3 Jeremy Barlow Lucasfilm Mike Baron Pop Mahn Wolfman, Kaluta, and Weiss recall their DC Comics journeys to Barsoom, Venus, and beyond Mike W. Barr Ron Marz BEYOND CAPES: John Carter Lives! . .11 Haden Blackman Bob McLeod Eliot R. Brown David Michelinie Monthly adventures on Barsoom in Marvel Comics’ John Carter, Warlord of Mars Jarrod and Allen Milgrom BACKSTAGE PASS: Who Shot Down Man from Atlantis? . .17 Jamie Buttery John Jackson Miller John Byrne John Nadeau The cancellation of this Marvel TV adaptation might not have been a result of low sales Paul Chadwick Jerry Ordway INTERVIEW: The “Twilight” Saga: A Conversation with Carol Serling . .25 Brian Ching John Ostrander Chris Claremont Steve Perry The widow of Twilight Zone mastermind and Planet of the Apes screenwriter Rod Serling Bob Cooper Thomas Powers shares her fond memories Dark Horse Comics Ron Randall Daniel DeAngelo Mike Richardson FLASHBACK: Star Wars at Dark Horse Comics: The Force is Strong within Them! . -

George Pal Papers, 1937-1986

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf2s2004v6 No online items Finding Aid for the George Pal Papers, 1937-1986 Processed by Arts Library-Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by D.MacGill; Arts Library-Special Collections University of California, Los Angeles, Library Performing Arts Special Collections, Room A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Phone: (310) 825-4988 Fax: (310) 206-1864 Email: [email protected] http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm © 1998 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the George Pal 102 1 Papers, 1937-1986 Finding Aid for the George Pal Papers, 1937-1986 Collection number: 102 UCLA Arts Library-Special Collections Los Angeles, CA Contact Information University of California, Los Angeles, Library Performing Arts Special Collections, Room A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Phone: (310) 825-4988 Fax: (310) 206-1864 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm Processed by: Art Library-Special Collections staff Date Completed: Unknown Encoded by: D.MacGill © 1998 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: George Pal Papers, Date (inclusive): 1937-1986 Collection number: 102 Origination: Pal, George Extent: 36 boxes (16.0 linear ft.) Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Arts Special Collections Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Shelf location: Held at SRLF. Please contact the Performing Arts Special Collections for paging information. Language: English. Restrictions on Access Advance notice required for access. -

Star Wars © 2012 Lucasfilm Ltd

THE RETRO COMICS EXPERIENCE! 1 2 A pril 20 .55 No 5 $ 8 . 9 l l l l A A . 2 2 ™ ™ 1 1 0 0 & & 2 2 . d d © © t t L L s s r r m m a a l l i i f f W W s s a a r r c c a a t t u u L L S S STARat D arWk HorAse CRomiScs! 3 0 8 2 6 7 7 2 8 5 6 LICENSED COMICS ISSUE: Indiana Jones • Edgar Rice Burroughs—Beyond Tarzan • Man from Atlantis 2 8 and an interview with Carol Serling, wife of “Twilight Zone” creator Rod Serling 1 Volume 1, Number 55 April 2012 Celebrating the Best The Retro Comics Experience! Comics of the '70s, '80s, '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich J. Fowlks COVER ARTIST Brian Koschack COVER COLORIST Dan Jackson COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Scott Allie Karl Kesel . BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 ™ Kevin J. Anderson Dave Land & Michael Aushenker Rick Leonardi . d FLASHBACK: Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Weird Worlds . .3 t L Jeremy Barlow Lucasfilm m l i Wolfman, Kaluta, and Weiss recall their DC Comics journeys to Barsoom, Venus, and beyond f Mike Baron Pop Mahn s a c Mike W. Barr Ron Marz u L BEYOND CAPES: John Carter Lives! . .11 2 Haden Blackman Bob McLeod 1 0 Monthly adventures on Barsoom in Marvel Comics’ John Carter, Warlord of Mars 2 Eliot R. Brown David Michelinie © . Jarrod and Allen Milgrom s n BACKSTAGE PASS: Who Shot Down Man from Atlantis ? . -

Origin 31 September 2020

Origin 31 September 2020 The official monthly publication of the National Fantasy Fan Federation’s History and Research Bureau. Origin recalls the past and seeks the future, dealing with both science fiction and fantasy and their place in the literary culture. Read our zine and contemplate our position in things. Edited by John Thiel, addressable at 30 N. 19th Street, Lafayette, Indiana 47904, [email protected] Staff Jeffrey Redmond, [email protected] , 1335 Beechwood NE, Grand Rapids, MI 49505-3830 Jon Swartz, [email protected] , 12115 Missel Thrush Court, Austin, TX 78750 Judy Carroll, [email protected] , 975 East 120 South, Spanish Fork, Utah 84660 Contents Editorial, The Sound of Laughter in the Hills, by John Thiel, page three Early Bantam Science Fiction Paperbacks, by Jon Swartz, page six Romance in Science Fiction by Jeffrey Redmond, page eleven The Beginning of the Beginning: SF & Fandom’s Background, by John Thiel, page thirteen Hard and Soft Science Fiction, by Judy Carroll, page sixteen EDITORIAL The Sound of Laughter in the Hills Off a ways there may be fun and merriment, but here where our interests are concentrated we have little chance to look up and out across those broader horizons. I find a sort of discursiveness to our present net activities and the net achieves a kind of concentration that has that broader range indicated rather than sensed. Like the following: Joe Siclari of the Fan History Project wrote to the last month’s issue of TNFF about the Fan History Project, assuming it would be of some interest here, and in the issue prior to that one he was also talking about the fan history project, and he has been a member of the NFFF right along, but several attempts to contact him via the email given on the roster received no response. -

AM a Fierce Green Fire Production Bios FINAL

Press Contact: Natasha Padilla, WNET 212.560.8824, [email protected] Press Materials: http://pbs.org/pressroom or http://thirteen.org/pressroom Websites: http://pbs.org/americanmasters , http://facebook.com/americanmasters , @PBSAmerMasters , http://pbsamericanmasters.tumblr.com , #AmericanMasters American Masters A Fierce Green Fire Premieres nationally Tuesday, April 22, 2014, 9-10 p.m. on PBS (check local listings) in honor of Earth Day Mark Kitchell Director, Producer and Writer Mark Kitchell is best known for Berkeley in the Sixties , which won the Audience Award at the 1990 Sundance Film Festival, was nominated for an Academy Award, and won other top honors. The film has become a well-loved classic, one of the defining documentaries about the protest movements that shook America during the 1960s. Since, he has worked in non-fiction television, made films for hire, taught at University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC), done freelance production and devoted over a decade to developing, making and distributing A Fierce Green Fire . Kitchell’s career began with Grand Theft Auto . He went to New York University (NYU) film school, where he made The Godfather Comes to Sixth St. , a cinéma vérité look at his neighborhood caught up in filming The Godfather II — for which he received another (student) Academy Award nomination. Marc N. Weiss Executive Producer Marc Weiss is best known as creator and executive producer of P.O.V. , the award-winning independent documentary series now preparing for its 27th season on PBS. He has been a leader in the independent media movement for 40+ years as a filmmaker, journalist, organizer and innovator in using the Internet to engage people on social issues. -

Challenger 42

1 CHALLENGER 42 Spring 2019 Guy H. Lillian III and Rose-Marie Lillian, editors 1390 Holly Avenue, Merritt Island FL 32952 [email protected] * 318-218-2345 GHLIII Press Publication #1252 CONTENTS The Challenger Welcome / Where it All Began: Thinking Machines GHLIII 3 Forget the Flying Cars, Where Is My Rosie? Rose-Marie Lillian 6 Metal Fever Andrew Hooper 8 Robotics – Past, Present and Future Derrick Houston 11 The Man Who Named the Robots Steven Silver 14 The Robot I Love Christopher Garcia 16 A.I. GHLIII (art: Charlie Williams) 18 Dōmo Arigatō, Mr. Roboto Rich Lynch 21 ‘Tis Pity She’s an Android W. J. Donovan (art: Kurt Erichsen) 23 They Walked Like Men GHLIII (art: Charlie Williams &c.) 29 The Shadow of Alfred Bester Anthony Tollin 43 Artificial Insouciance Nic Farey 44 Writer to Writer Michelle Bonnell 46 The Challenger Musical Theater Survey Mike Resnick 47 The Stepford Story Jim Ivers 51 The Challenger Tribute GHLIII 61 The Joker Side of the Force Joseph Major 62 Dissenting on Clifford Simak Joseph L. Green 65 Original Factory Settings Taral Wayne (art: the author) 69 Dissecting the Alien Greg Benford 76 My Ejection from Loscon, 2018 Greg Benford 86 The Chorus Lines you, you and you! 91 Battle of the Toy Robots John Purcell 103 Farewells for Now Guy & Rosy (art: Teddy Harvia & Brad Foster) 105 Challenger no. 42 is © 2019 by Guy H. Lillian III. All individual rights revert to contributors upon print and electronic publication. The challenger welcome And indeed is so: Rose-Marie and I bid you welcome to Challenger no. -

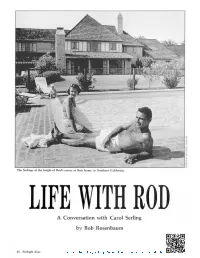

Life with Rod: a Conversation with Carol Serling

It would be diffiCl//t to imagine a T wi light Zone without the genius of Rod Serli/lg. Al1d it's likely Rod would IJa ve had far less impact on the televisioll industry wilii out the Ileip al1d support of Carol Kramer Serlitlg, his wife. Their marriage provided Rod with sufficient motivation to persevere il1 spite of "forty rejection slips ill a row, " (as he once described it), leave tIle security of CillCillllClti, and head for New York City just ill time to assume a pioneering role in th e developing TV medium, Television was lucky to have Serlillg. Lotlg before the creatioH of The Twi light Zone, he had participated in the early shaping of TV drama, writiHg for such landmark programs as the Hall mark Hall of Fame, Studio One, Kraft Television Theater, alld Play house 90. Rod was o l1 e of a hmldful ",...-;or of gifted young writers to w hom the illdustry fumed for direction duril1g its "Go ld€l1 Age". By 1959, tlte year The Twilight Zone had its debut, Serlillg had received three TV Emmys and a Peabody A ward - tlte first ever awarded to a w riter. Rod and Carol working together on a radi o broadca st at Antioch College . TIl e rapid trallSitioll from strugglillg playwright to successful producer put azine, anlollg other activ ities. Carol ers, which is another story. When he pressw 'es a l l Serling alld his fal/lily. graciously cOl/ sented to this interview, came back after the war, he took a "He was bas ically a writer," Carol it'l which she offers us some personal college work-study job at a rehabili t a~ recalls, "and a w riter is a very solitary perspectives 011 her life witl1 a tion hospital near Chicago, because he persall who does his best work off by remarkable man. -

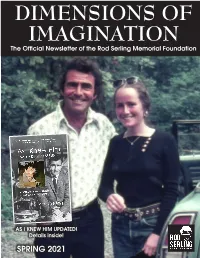

Newsletter Spring 2021

DIMENSIONS OF IMAGINATION The Official Newsletter of the Rod Serling Memorial Foundation AS I KNEW HIM UPDATED! Details inside! SPRING 2021 FOUNDATION NOTES FROM NICK An Update from RSMF President Nick Parisi Hello everyone and welcome to work. Guy has been a professional hope you will let us utilize your work our spring 2021 newsletter! There’s illustrator for over 30 years and in other fundraising efforts. We’ll be lots going on in our little corner of has drawn every major character in touch! the Serling-verse to cover this time and worked with every big name around. in the comics industry imaginable. Since our prior newsletter, a few He’s also a passionate Rod Serling interesting Serling items have In our previous issue, we fan and generously offered to surfaced: mentioned our plans to erect a donate his time and talent to us for statue in Rod Serling’s honor in this project. Thanks, Guy! Check Season one of Betty White’s 1972 Binghamton, New York. By the out www.guydorianart.com for series, PET SET, was recently added time you read this, we will have samples of Guy’s incredible work. to Amazon Prime, and episode started or will soon start our online 20 features a guest appearance campaign to raise funds for this When we initiated this project, one from Rod and his adorable “son,” ambitious project. One of the of our newest board members, Michael, the family’s Irish Setter. many fantastic items that we plan Shelley McKay Young, put out If you had any doubt of Rod’s to offer in exchange for donations a call for artwork and several affection for animals – and dogs is the first official Rod Serling talented artists responded with specifically – check this out.