Weaving the Dark Web: Legitimacy on Freenet, Tor, and I2P (Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PVC Technical Specifications V.1.0

Pryvate™ Ltd. Functional & Technical Specifications PVC Technical Specifications V.1.0 APRIL 10, 2018 © PRYVATE™ 2018. PRYVATE™ is a suite of security products from Criptyque Ltd. Registered in the Cayman Islands. PRYVATE™ Is a brand wholly owned by CRIPTYQUE Ltd. Pryvate™ Ltd. Functional & Technical Specifications TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 GENERAL INFORMATION 5 1.1 Scope 1.2 Current Platform Summary 2 FUNCTIONAL TECH SPECIFICATIONS 5 2.1 Encrypted Voice Calls (VOIP) 2.2 Off Net Calling 2.3 Secure Conferencing 2.4 Encrypted Video Calls 2.5 Encrypted Instant Message (IM) 2.6 Notification of Screenshots 2.7 Encrypted Email 2.8 Secure File Transfer & Storage 2.9 Pin-Encrypted Mobile Protection 2.10 Multiple Account Management 2.11 Secure managed conversations 2.12 Anti-Blocking 3 HYBRIDIZATION 13 3.1 Voice / Video / Messaging 3.2 File Storage / Archival 3.3 Pryvate Crypto Wallet 3.3.1 Two-Wallet Solution 3.3.2 Three Methods 3.3.3 Enterprise Multi - by Pryvate 3.3.4 Risks of Cryptocurrency Wallets 3.4 Decentralized Email 3.5 Pryvate Dashboard 4 PERFORMANCE REQUIREMENTS 20 4.1 System Maintenance 4.2 Failure Contingencies 4.3 Customization and Flexibility 4.4 Equipment 4.5 Software 4.6 Interface / UI 5 CONCLUSION 21 6 APPENDIX 22 © PRYVATE™ 2018. PRYVATE™ is a suite of security products from Criptyque Ltd. Registered in the Cayman Islands. PRYVATE™ Is a brand wholly owned by CRIPTYQUE Ltd. Pryvate™ Ltd. Functional & Technical Specifications Acronyms: Definitions SCP = Secure Communications Platform Crypto= Cryptocurrency IPFS= Interplanetary File System ZRTP= ("Z" is a reference to its inventor, Zimmermann; "RTP" stands for Real-time Transport Protocol) it is a cryptographic key-agreement protocol to negotiate the keys for encryption between two end points in a Voice over Internet Protocol Diffie-Hellman= A method of securely exchanging cryptographic keys over a public channel and was one of the first public-key protocols as originally conceptualized by Ralph Merkle and named after Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman. -

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

The New England College of Optometry Peer to Peer (P2P) Policy

The New England College of Optometry Peer To Peer (P2P) Policy Created in Compliance with the Higher Education Opportunity Act (HEOA) Peer-to-Peer File Sharing Requirements Overview: Peer-to-peer (P2P) file sharing applications are used to connect a computer directly to other computers in order to transfer files between the systems. Sometimes these applications are used to transfer copyrighted materials such as music and movies. Examples of P2P applications are BitTorrent, Gnutella, eMule, Ares Galaxy, Megaupload, Azureus, PPStream, Pando, Ares, Fileguri, Kugoo. Of these applications, BitTorrent has value in the scientific community. For purposes of this policy, The New England College of Optometry (College) refers to the College and its affiliate New England Eye Institute, Inc. Compliance: In order to comply with both the intent of the College’s Copyright Policy, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) and with the Higher Education Opportunity Act’s (HEOA) file sharing requirements, all P2P file sharing applications are to be blocked at the firewall to prevent illegal downloading as well as to preserve the network bandwidth so that the College internet access is neither compromised nor diminished. Starting in September 2010, the College IT Department will block all well-known P2P ports on the firewall at the application level. If your work requires the use of BitTorrent or another program, an exception may be made as outlined below. The College will audit network usage/activity reports to determine if there is unauthorized P2P activity; the IT Department does random spot checks for new P2P programs every 72 hours and immediately blocks new and emerging P2P networks at the firewall. -

Internet Censorship and Resistance May 15, 2009 1 / 32 Historical Censorship

INTERNET CENSORSHIP AND RESISTANCE Joseph Bonneau [email protected] (thanks to Steven Murdoch) Computer Laboratory Gates Scholars' Symposium 2010 Joseph Bonneau (University of Cambridge) Internet Censorship and Resistance May 15, 2009 1 / 32 Historical Censorship He who controls the past controls the future, and he who controls the present controls the past —George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty Four, 1949 Joseph Bonneau (University of Cambridge) Internet Censorship and Resistance May 15, 2009 2 / 32 Historical Censorship He who controls the past controls the future, and he who controls the present controls the past —George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty Four, 1949 Joseph Bonneau (University of Cambridge) Internet Censorship and Resistance May 15, 2009 2 / 32 Information as a Human Right Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expres- sion; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without inter- ference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers. —Article 19, UN Declaration of Human Rights (1948) Joseph Bonneau (University of Cambridge) Internet Censorship and Resistance May 15, 2009 3 / 32 Information as a Human Right The final freedom, one that was probably inherent in what both President and Mrs. Roosevelt thought about and wrote about all those years ago, ... is the freedom to connect—the idea that governments should not prevent people from con- necting to the internet, to websites, or to each other... a new information curtain is descending across much of the world. —Hillary Clinton, US Secretary of State (2010) Joseph Bonneau (University of Cambridge) Internet Censorship and Resistance May 15, 2009 3 / 32 The Internet Dream The Net treats censorship as damage and routes around it. -

Elgg Social Networking

Elgg Social Networking Create and manage your own social network site using this free open-source tool Mayank Sharma BIRMINGHAM - MUMBAI Elgg Social Networking Copyright © 2008 Packt Publishing All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews. Every effort has been made in the preparation of this book to ensure the accuracy of the information presented. However, the information contained in this book is sold without warranty, either express or implied. Neither the author, Packt Publishing, nor its dealers or distributors will be held liable for any damages caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by this book. Packt Publishing has endeavored to provide trademark information about all the companies and products mentioned in this book by the appropriate use of capitals. However, Packt Publishing cannot guarantee the accuracy of this information. First published: March 2008 Production Reference: 1190308 Published by Packt Publishing Ltd. 32 Lincoln Road Olton Birmingham, B27 6PA, UK. ISBN 978-1-847192-80-6 www.packtpub.com Cover Image by Vinayak Chittar ([email protected]) [ FM-2 ] Credits Author Project Manager Mayank Sharma Patricia Weir Reviewer Project Coordinator Diego Ramirez Patricia Weir Senior Acquisition Editor Indexer David Barnes Monica Ajmera Development Editor Proofreader Rashmi Phadnis Nina Hasso Technical Editor Production Coordinator Ajay Shanker Aparna Bhagat Editorial Team Leader Cover Designer Mithil Kulkarni Aparna Bhagat [ FM-3 ] About the Author Mayank Sharma is a contributing editor at SourceForge, Inc's Linux.com. -

An Evolving Threat the Deep Web

8 An Evolving Threat The Deep Web Learning Objectives distribute 1. Explain the differences between the deep web and darknets.or 2. Understand how the darknets are accessed. 3. Discuss the hidden wiki and how it is useful to criminals. 4. Understand the anonymity offered by the deep web. 5. Discuss the legal issues associated withpost, use of the deep web and the darknets. The action aimed to stop the sale, distribution and promotion of illegal and harmful items, including weapons and drugs, which were being sold on online ‘dark’ marketplaces. Operation Onymous, coordinated by Europol’s Europeancopy, Cybercrime Centre (EC3), the FBI, the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) and Eurojust, resulted in 17 arrests of vendors andnot administrators running these online marketplaces and more than 410 hidden services being taken down. In addition, bitcoins worth approximately USD 1 million, EUR 180,000 Do in cash, drugs, gold and silver were seized. —Europol, 20141 143 Copyright ©2018 by SAGE Publications, Inc. This work may not be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means without express written permission of the publisher. 144 Cyberspace, Cybersecurity, and Cybercrime THINK ABOUT IT 8.1 Surface Web and Deep Web Google, Facebook, and any website you can What Would You Do? find via traditional search engines (Internet Explorer, Chrome, Firefox, etc.) are all located 1. The deep web offers users an anonym- on the surface web. It is likely that when you ity that the surface web cannot provide. use the Internet for research and/or social What would you do if you knew that purposes you are using the surface web. -

Everyone's Guide to Bypassing Internet Censorship

EVERYONE’S GUIDE TO BY-PASSING INTERNET CENSORSHIP FOR CITIZENS WORLDWIDE A CIVISEC PROJECT The Citizen Lab The University of Toronto September, 2007 cover illustration by Jane Gowan Glossary page 4 Introduction page 5 Choosing Circumvention page 8 User self-assessment Provider self-assessment Technology page 17 Web-based Circumvention Systems Tunneling Software Anonymous Communications Systems Tricks of the trade page 28 Things to remember page 29 Further reading page 29 Circumvention Technologies Circumvention technologies are any tools, software, or methods used to bypass Inter- net filtering. These can range from complex computer programs to relatively simple manual steps, such as accessing a banned website stored on a search engine’s cache, instead of trying to access it directly. Circumvention Providers Circumvention providers install software on a computer in a non-filtered location and make connections to this computer available to those who access the Internet from a censored location. Circumvention providers can range from large commercial organi- zations offering circumvention services for a fee to individuals providing circumven- tion services for free. Circumvention Users Circumvention users are individuals who use circumvention technologies to bypass Internet content filtering. 4 Internet censorship, or content filtering, has become a major global problem. Whereas once it was assumed that states could not control Internet communications, according to research by the OpenNet Initiative (http://opennet.net) more than 25 countries now engage in Internet censorship practices. Those with the most pervasive filtering policies have been found to routinely block access to human rights organi- zations, news, blogs, and web services that challenge the status quo or are deemed threatening or undesirable. -

Shedding Light on Mobile App Store Censorship

Shedding Light on Mobile App Store Censorship Vasilis Ververis Marios Isaakidis Humboldt University, Berlin, Germany University College London, London, UK [email protected] [email protected] Valentin Weber Benjamin Fabian Centre for Technology and Global Affairs University of Telecommunications Leipzig (HfTL) University of Oxford, Oxford, UK Humboldt University, Berlin, Germany [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This paper studies the availability of apps and app stores across app stores, censorship, country availability, mobile applications, countries. Our research finds that users in specific countries do China, Russia not have access to popular app stores due to local laws, financial reasons, or because countries are on a sanctions list that prohibit ACM Reference Format: Vasilis Ververis, Marios Isaakidis, Valentin Weber, and Benjamin Fabian. foreign businesses to operate within its jurisdiction. Furthermore, 2019. Shedding Light on Mobile App Store Censorship. In 27th Conference this paper presents a novel methodology for querying the public on User Modeling, Adaptation and Personalization Adjunct (UMAP’19 Ad- search engines and APIs of major app stores (Google Play Store, junct), June 9–12, 2019, Larnaca, Cyprus. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 6 pages. Apple App Store, Tencent MyApp Store) that is cross-verified by https://doi.org/10.1145/3314183.3324965 network measurements. This allows us to investigate which apps are available in which country. We primarily focused on the avail- ability of VPN apps in Russia and China. Our results show that 1 INTRODUCTION despite both countries having restrictive VPN laws, there are still The widespread adoption of smartphones over the past decade saw many VPN apps available in Russia and only a handful in China. -

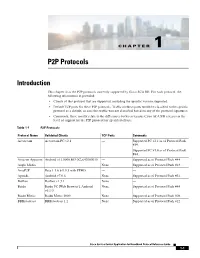

P2P Protocols

CHAPTER 1 P2P Protocols Introduction This chapter lists the P2P protocols currently supported by Cisco SCA BB. For each protocol, the following information is provided: • Clients of this protocol that are supported, including the specific version supported. • Default TCP ports for these P2P protocols. Traffic on these ports would be classified to the specific protocol as a default, in case this traffic was not classified based on any of the protocol signatures. • Comments; these mostly relate to the differences between various Cisco SCA BB releases in the level of support for the P2P protocol for specified clients. Table 1-1 P2P Protocols Protocol Name Validated Clients TCP Ports Comments Acestream Acestream PC v2.1 — Supported PC v2.1 as of Protocol Pack #39. Supported PC v3.0 as of Protocol Pack #44. Amazon Appstore Android v12.0000.803.0C_642000010 — Supported as of Protocol Pack #44. Angle Media — None Supported as of Protocol Pack #13. AntsP2P Beta 1.5.6 b 0.9.3 with PP#05 — — Aptoide Android v7.0.6 None Supported as of Protocol Pack #52. BaiBao BaiBao v1.3.1 None — Baidu Baidu PC [Web Browser], Android None Supported as of Protocol Pack #44. v6.1.0 Baidu Movie Baidu Movie 2000 None Supported as of Protocol Pack #08. BBBroadcast BBBroadcast 1.2 None Supported as of Protocol Pack #12. Cisco Service Control Application for Broadband Protocol Reference Guide 1-1 Chapter 1 P2P Protocols Introduction Table 1-1 P2P Protocols (continued) Protocol Name Validated Clients TCP Ports Comments BitTorrent BitTorrent v4.0.1 6881-6889, 6969 Supported Bittorrent Sync as of PP#38 Android v-1.1.37, iOS v-1.1.118 ans PC exeem v0.23 v-1.1.27. -

Threat Modeling and Circumvention of Internet Censorship by David Fifield

Threat modeling and circumvention of Internet censorship By David Fifield A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor J.D. Tygar, Chair Professor Deirdre Mulligan Professor Vern Paxson Fall 2017 1 Abstract Threat modeling and circumvention of Internet censorship by David Fifield Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science University of California, Berkeley Professor J.D. Tygar, Chair Research on Internet censorship is hampered by poor models of censor behavior. Censor models guide the development of circumvention systems, so it is important to get them right. A censor model should be understood not just as a set of capabilities|such as the ability to monitor network traffic—but as a set of priorities constrained by resource limitations. My research addresses the twin themes of modeling and circumvention. With a grounding in empirical research, I build up an abstract model of the circumvention problem and examine how to adapt it to concrete censorship challenges. I describe the results of experiments on censors that probe their strengths and weaknesses; specifically, on the subject of active probing to discover proxy servers, and on delays in their reaction to changes in circumvention. I present two circumvention designs: domain fronting, which derives its resistance to blocking from the censor's reluctance to block other useful services; and Snowflake, based on quickly changing peer-to-peer proxy servers. I hope to change the perception that the circumvention problem is a cat-and-mouse game that affords only incremental and temporary advancements. -

State of the Art in Lightweight Symmetric Cryptography

State of the Art in Lightweight Symmetric Cryptography Alex Biryukov1 and Léo Perrin2 1 SnT, CSC, University of Luxembourg, [email protected] 2 SnT, University of Luxembourg, [email protected] Abstract. Lightweight cryptography has been one of the “hot topics” in symmetric cryptography in the recent years. A huge number of lightweight algorithms have been published, standardized and/or used in commercial products. In this paper, we discuss the different implementation constraints that a “lightweight” algorithm is usually designed to satisfy. We also present an extensive survey of all lightweight symmetric primitives we are aware of. It covers designs from the academic community, from government agencies and proprietary algorithms which were reverse-engineered or leaked. Relevant national (nist...) and international (iso/iec...) standards are listed. We then discuss some trends we identified in the design of lightweight algorithms, namely the designers’ preference for arx-based and bitsliced-S-Box-based designs and simple key schedules. Finally, we argue that lightweight cryptography is too large a field and that it should be split into two related but distinct areas: ultra-lightweight and IoT cryptography. The former deals only with the smallest of devices for which a lower security level may be justified by the very harsh design constraints. The latter corresponds to low-power embedded processors for which the Aes and modern hash function are costly but which have to provide a high level security due to their greater connectivity. Keywords: Lightweight cryptography · Ultra-Lightweight · IoT · Internet of Things · SoK · Survey · Standards · Industry 1 Introduction The Internet of Things (IoT) is one of the foremost buzzwords in computer science and information technology at the time of writing. -

Disinformation, and Influence Campaigns on Twitter 'Fake News'

Disinformation, ‘Fake News’ and Influence Campaigns on Twitter OCTOBER 2018 Matthew Hindman Vlad Barash George Washington University Graphika Contents Executive Summary . 3 Introduction . 7 A Problem Both Old and New . 9 Defining Fake News Outlets . 13 Bots, Trolls and ‘Cyborgs’ on Twitter . 16 Map Methodology . 19 Election Data and Maps . 22 Election Core Map Election Periphery Map Postelection Map Fake Accounts From Russia’s Most Prominent Troll Farm . 33 Disinformation Campaigns on Twitter: Chronotopes . 34 #NoDAPL #WikiLeaks #SpiritCooking #SyriaHoax #SethRich Conclusion . 43 Bibliography . 45 Notes . 55 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This study is one of the largest analyses to date on how fake news spread on Twitter both during and after the 2016 election campaign. Using tools and mapping methods from Graphika, a social media intelligence firm, we study more than 10 million tweets from 700,000 Twitter accounts that linked to more than 600 fake and conspiracy news outlets. Crucially, we study fake and con- spiracy news both before and after the election, allowing us to measure how the fake news ecosystem has evolved since November 2016. Much fake news and disinformation is still being spread on Twitter. Consistent with other research, we find more than 6.6 million tweets linking to fake and conspiracy news publishers in the month before the 2016 election. Yet disinformation continues to be a substantial problem postelection, with 4.0 million tweets linking to fake and conspiracy news publishers found in a 30-day period from mid-March to mid-April 2017. Contrary to claims that fake news is a game of “whack-a-mole,” more than 80 percent of the disinformation accounts in our election maps are still active as this report goes to press.