UC Berkeley Room One Thousand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parallels and Analogies in the Interwar Architecture in Latvia and Czechoslovakia

Scientific Journal of Latvia University of Agriculture Landscape Architecture and Art, Volume 10, Number 10 Parallels and Analogies in the Interwar Architecture in Latvia and Czechoslovakia Renāte Čaupale, Riga Technical University, Latvia University of Agriculture Abstract. The interconnections of the interactions between the art and architecture of the Latvian and Czechoslovakian nations are relatively fragmented. However, there is one large European cultural space in which both parallels and analogies can be found, as required by the communicative role of art and architecture. In the 1920s and 1930s, a European architecture that was founded on modern features could be found in the architecture of the new Latvian state. Art Deco aesthetics was one of the operative events of the interwar period. Its expression changed along with the changes occurring during this time period, retaining the decorativeness principles of Art Deco. Art Deco aesthetics encompass several distinct but related design trends, including the following: interpretation of elements of folklore – Ansis Cīrulis in Latvia and Pavel Janák in Czechoslovakia authored masterfully designed interior examples. Regardless of their creative potential after the First Wold War, artists and architects in many new states were drawn into the stream of contemporary trends – the folkloristic style, which became one of the decisive sources of inspiration for demonstrating national self-determination, which, in turn, is typical of all cultures and civilisations and can sometimes be international. An analogous interpretation of folklore brings these processes together, which allows them to be identified as folkloristic Art Deco trends. There are moments when folkloristic Art Deco as a component of Modernism art and architecture of the 1920-30s organically foreshadows the aesthetics of pre-postmodernism; modernization of the classic form, which has been highlighted directly in the period of the leader cult common in new states. -

EASTERN AVANT-GARDE ORBIT II DIGITAL DELIGHTS | LIST NO. 4 DECEMBER 2019 Dear Clients, Colleagues and Friends

EASTERN AVANT-GARDE ORBIT II DIGITAL DELIGHTS | LIST NO. 4 DECEMBER 2019 Dear clients, colleagues and friends, I am hereby glad to present my new short list »Digital Delights«, edition no. 4. The following illustrated list contains 30 new arrivals as well as carefully selected items from my stock related to the Central and Eastern European Avant-Garde orbit. Illustrated books and magazines, each created by major proponents of Bulgarian, Czech, Estonian, Hungarian, Latvian, Romanian, Russian and Yugoslavian avant-garde movements from the 1920s and 1930s are waiting to be discovered by you. Highlights include the first ever printed poems by Paul Celan (pos. 1), the striking "Moholy- Nagy issue" of the Hungarian periodical MA (7), the spectacularly covered magazine »Kreisā Fronte« from Latvia (8-11), »The Adventures of The Five Little Roosters Gang«, probably the most breathtaking of all surrealist children books (29), and some particularly rare Bulgarian items, created by a short lifted but nevertheless fervent modernist scene around Geo Milev (please also consider my monograph »Bulgarian Modernism. Books and Magazines 1919-1934« still available in my web-shop). The list is in alphabetical order and the descriptions are mainly done in English, some of them in German language however. English translations on demand. So, please enjoy browsing, watching and reading, and of course I am very much looking forward to your feedback and orders. Yours, 1 1 Paul CELAN: [Drei Gedichte in] Agora. Colecție internațională de artă și literatură [Internationale Sammlung von Kunst und Literatur]. Îngrijită de [Hg. v.] Ion Caraion și Virgil Ierunca. Vol. 1 [Alles Erschienene] (= Colecție »Sisiph«). -

Taking a Stand? Debating the Bauhaus and Modernism, Heidelberg: Arthistoricum.Net 2021, P

Damnatio Memoriae. The Case of Mart Stam Simone Hain Hain, Simone, Damnatio Memoriae. The Case of Mart Stam, in: Bärnreuther, Andrea (ed.), Taking a Stand? Debating the Bauhaus and Modernism, Heidelberg: arthistoricum.net 2021, p. 359-573, https://doi.org/10.11588/arthistoricum.843.c11919 361 Simone Hain [ B ] What do we understand by taking a stand regarding architecture and design, and particularly of the Bauhaus and Modernism? architectural historiography As early as 1932, 33-year-old Mart Stam was preoccupied with the of modernism idea that he might be counted as dead as far as architectural his- tory, or rather the «West», was concerned, because for over a year and a half he had failed to provide new material for art history. «We Are Not Working Here with the Intention of Influencing How Art Develops and Making New Material Available to Art History» On August 20th, 1932, he wrote to Sigfried Giedion, the most im- portant art historian for architects: «You will be amazed to receive another little letter from me after I have been dead for a year and a half. Yes, I am immersed in our Russian work, in one of the most [ B ] difficult tasks that will ever exist. I know that we won’t be able to build a lot of flawless buildings here, that we won’t be able to produce wonderful material compositions, that we won’t even be able to implement pure floor plans and apartment types, maybe not even flawless city plans. [...] we are not working here with the intention of influencing how art develops and making new mate- rial available to art history, but rather because we are witnessing societal projects of modernism a great cultural-historical development that is almost unprecedent- reshaping the world ed in its scope and extent [...].»1 Stam describes his activities in Russia ex negativo, knowing full well that in doing so he is violating the well-established rela- tionship between himself and Giedion and all the rules of the game in the industry. -

Introduction

introduction Writing a Postwar History The biggest victim of the Stalinization of architecture was housing. [Karel] Teige would have recoiled in horror at the endless drab rows of prefabricated boxes of mass housing proliferating around all the major cities of Czechoslo- vakia. Here was the exact antithesis of his utopia of collective dwelling, resem- bling more the housing barracks of capitalist rent exploitation and greed than the joyful housing developments of a new socialist paradise. The result was one of the most depressing collections of banality in the history of Czech architecture, one that still mars the architectural landscape of this small coun- try and will be difficult—if not impossible—to erase from its map for decades, if not centuries. Eric Dluhosch, 2002 Few building types are as vilified as the socialist housing block. Built by the thousands in Eastern Europe in the decades after World War II, the apartment buildings of the planned economy are notorious for problems such as faulty construction methods, lack of space, nonexistent landscaping, long-term maintenance lapses, and general ugliness. The typical narrative of the con- struction and perceived failure of these blocks, the most iconic of which was the structural panel building (panelový dům or panelák, for short, in Czech), places the blame with a Soviet-imposed system of building that was forced upon the unwilling countries of Eastern Europe after the Communists came to power.1 This shift not only brought neoclassicism and historicism to the region but also ended the idealistic era of avant-garde modernism, which dis- appeared with the arrival of fascism in many European countries but sur- vived in Czechoslovakia through World War II. -

Surrealism in and out of the Czechoslovak New Wave

Introduction Surrealism In and Out of the Czechoslovak New Wave Figure I.1 A poet’s execution. A Case for the Young Hangman (Případ pro začínajícího kata, Pavel Juráček, 1969) ©Ateliéry Bonton Zlín, reproduced by courtesy of Bonton Film. 2 | Avant-Garde to New Wave The abrupt, rebellious flowering of cinematic accomplishment in the Czechoslovakia of the 1960s was described at the time as the ‘Czech film miracle’. If the term ‘miracle’ referred here to the very existence of that audacious new cinema, it could perhaps also be applied to much of its content: the miraculous and marvellous are integral to the revelations of Surrealism, a movement that claimed the attention of numerous 1960s filmmakers. As we shall see, Surrealism was by no means the only avant-garde tradition to make a significant impact on this cinema. But it did have the most pervasive influence. This is hardly surprising, as Surrealism has been the dominant mode of the Czech avant-garde during the twentieth century, even if at certain periods that avant-garde has not explicitly identified its work as Surrealist. Moreover, the very environment of the Czech capital of Prague has sometimes been considered one in which Surrealism was virtually predestined to take root. The official founder of the Surrealist movement, André Breton, lent his imprimatur to the founding of a Czech Surrealist group when he remarked on the sublimely conducive locality of the capital, which Breton describes as ‘one of those cities that electively pin down poetic thought’ and ‘the magic capital of old Europe’.1 Indeed, it would seem a given that Czech cinema should evince a strong Surrealist tendency, especially when we consider the Surrealists’ own long-standing passion for this most oneiric of art forms. -

Jury Citation This Is the Inaugural Year of the Czech Architecture Awards

Jury citation This is the inaugural year of the Czech Architecture Awards, introduced by the Czech Chamber of Architects. Over 400 projects completed within the last five years from nearly every region of the Czech Republic were submitted, ranging from private houses to offices, public projects to cultural buildings, and education programmes to regeneration projects, all of which have been reviewed by a specially assembled Jury of architects and designers. This is a brave and forward thinking programme which aims to bring to the public theatre a critical debate focused on the demand for excellence within the construction industry. Even braver is that the Jury for this special prize has been assembled from an international stage of many European states; Holland, Germany, Slovakia, Belgium, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and Spain, in turn opening the debate to a wider international audience beyond the borders of the host country. It is of particular note however, that through an extensive judging process resulting with a shortlist of eight finalists including unanimous winner, non of the projects featured were built within the capital city, Prague. This suggests a broad depth of architectural endeavour for this country with an ambition to build high quality work but also raises worrying trends for a city which sees an intensity of many contemporary urban issues. As part of a three day trip, the Jury travelled the length and breadth of the Czech Republic to interrogate the architects and owners of projects for historical centres, projects in landscape settings, projects for domestic clients, regeneration and renovation projects. However it is also worrying to note an absence of meaningful projects managing the wider social concerns of mass housing or schools within urban settings. -

Terrible Turk”

Chapter 1 The Return of the “Terrible Turk” It seems that they [the Turks] were made only to murder and destroy. In the history of the Turkish nation you will find nothing but fighting, rob- bery, and murder. Every nation has turbulent times in its past, but along- side them also times that are crowned with the marvelous fruits of quiet effort and beneficial work; our nation, for example, has the age of the Hussites, but also the era of the Fathers of Our Country – the unforget- table Charleses. But in the history of the Turks you would search in vain for even a short period devoted to quiet, useful patriotic work. That is also why the images compiled here, in which only fear and terror and gloomy desolation reign, might seem chilling. Nevertheless, the history of the Turks is important, for the fight that Europe has conducted in its defense against the nations of this race has been waged by Christians alone and by the nations of our monarchy in particular. For this reason, the main consideration is given to the scenes that unfolded either in the countries of the Balkan Peninsula or those of Austria-Hungary. kodym, 18791 There have been few other non-Christian figures in European history that have been the object of such a vast range of visual representations as “the Turk.” From the warrior depicted in medieval and early modern German woodcuts, to the Turk as a symbol of wealth woven into the patterns of Renaissance French carpets, the captive Sultan who appeared on the stages of 18th-century Vene- tian opera houses, not to mention the pipe-smoking Turk on the signboards of coffee shops in many European cities and the harem women pictured in 19th- century Orientalist paintings, images of the Turks have accompanied Euro- peans for centuries. -

Surrealism-Revolution Against Whiteness

summer 1998 number 9 $5 TREASON TO WHITENESS IS LOYALTY TO HUMANITY Race Traitor Treason to whiteness is loyaltyto humanity NUMBER 9 f SUMMER 1998 editors: John Garvey, Beth Henson, Noel lgnatiev, Adam Sabra contributing editors: Abdul Alkalimat. John Bracey, Kingsley Clarke, Sewlyn Cudjoe, Lorenzo Komboa Ervin.James W. Fraser, Carolyn Karcher, Robin D. G. Kelley, Louis Kushnick , Kathryne V. Lindberg, Kimathi Mohammed, Theresa Perry. Eugene F. Rivers Ill, Phil Rubio, Vron Ware Race Traitor is published by The New Abolitionists, Inc. post office box 603, Cambridge MA 02140-0005. Single copies are $5 ($6 postpaid), subscriptions (four issues) are $20 individual, $40 institutions. Bulk rates available. Website: http://www. postfun. com/racetraitor. Midwest readers can contact RT at (312) 794-2954. For 1nformat1on about the contents and ava1lab1l1ty of back issues & to learn about the New Abol1t1onist Society v1s1t our web page: www.postfun.com/racetraitor PostF un is a full service web design studio offering complete web development and internet marketing. Contact us today for more information or visit our web site: www.postfun.com/services. Post Office Box 1666, Hollywood CA 90078-1666 Email: [email protected] RACE TRAITOR I SURREALIST ISSUE Guest Editor: Franklin Rosemont FEATURES The Chicago Surrealist Group: Introduction ....................................... 3 Surrealists on Whiteness, from 1925 to the Present .............................. 5 Franklin Rosemont: Surrealism-Revolution Against Whiteness ............ 19 J. Allen Fees: Burning the Days ......................................................3 0 Dave Roediger: Plotting Against Eurocentrism ....................................32 Pierre Mabille: The Marvelous-Basis of a Free Society ...................... .40 Philip Lamantia: The Days Fall Asleep with Riddles ........................... .41 The Surrealist Group of Madrid: Beyond Anti-Racism ...................... -

2009 Druh Dokumentu: XPCA Voľby: Číslovanie Kategórií Publ.Činno

Zoznam publikačnej činnosti a ohlasov Roky vykazovania: 2009 Druh dokumentu: XPCA Voľby: číslovanie kategórií publ.činnosti, zoradiť do skupín KPČ, zobrazenie systémového čísla záznamu, odsadenie celého záznamu doprava; Štatistika: kategória publikačnej činnosti, kategória ohlasov; Triedenie: skupina kategórie publikačnej činnosti, kategória publikačnej činnosti, meno prvého autora; Zobrazovací formát: HSO - modifikácia STN ISO 690 s ohlasmi - všetci autori Skupina A1 - Knižné publikácie charakteru vedeckej monografie (AAA,AAB, ABA, ABB) AAA Vedecké monografie vydané v zahraničných vydavateľstvách AAA01 0027910 KOLESÁR, Zdeno. Kapitoly z dějin designu. II. vydanie, doplnené a revidované. Praha, Česká republika : Vysoká škola uměleckoprůmyslová, 2009. 178 s. [9 AH]. Dostupné na internete: <http://www. vsup.cz/>. ISBN 978-80-86863-28-3. AAB Vedecké monografie vydané v domácich vydavateľstvách AAB01 0029875 RUSINA, Ivan. 59 60 61 : Vysoká škola výtvarných umení v Bratislave 1949-2009 : Academy of fine arts and design 1949-2009. 1. vyd. Bratislava, 2009 ; Bratislava : Vysoká škola výtvarných umení. 299 s. [10 AH]. Dostupné na internete: <http://www.vsvu.sk>. ISBN 978-80-89259-25-0. ABB Štúdie v časopisoch a zborníkoch charakteru vedeckej monografie vydané v domácich vydavateľstvách ABB01 0030081 JABLONSKÁ, Beata. Jednotlivci v príbehu postmoderných dejín. In Osemdesiate: Postmoderna v slovenskom výtvarnom umení 1985-1992. - Bratislava, Slovensko : SNG, 2009. ISBN 978-80-8059-140-3, s. 22-109, [4 AH]. Dostupné na internete: <http://www.sng.sk>. Skupina A2 - Ostatné knižné publikácie (ACA, ACB, BAA, BAB, BCB, BCI, EAI, CAA, CAB, EAJ, FAI) BCB Učebnice pre základné a stredné školy BCB01 0029623 ČARNÝ, Ladislav - FERLIKOVÁ, Klára - PONDELÍKOVÁ, Renáta - ČARNÁ, Daniela. Výtvarná výchova : 5. ročník základných škôl. Aut. -

Czech Republic Today

Rich in History 1 2 Magic Crossroads Whenever European nations were set in motion, they met in a rather small area called the Czech Republic today. Since the early Middle Ages, this area was crossed by long trade routes from the severe North to the sunny South; at the beginning of the first millennium, Christianity emerged from the West, and at its end communism arrived from the East. For six hundred years, the country was an independent Czech kingdom, for three hundred years, it belonged among Austro-Hungarian Empire lands, and since 1918 it has been a republic. In the 14th century, under the Bohemian and German King and Roman Emperor Charles IV, as well as in the 16th century under the Emperor Rudolf II, the country enjoyed a favourable position in European history and also played a great role internationally in the arts and in social affairs. In 1989, the whole world admired the Czechoslovak “velvet revolution” lead by charismatic dramatist Václav Havel, which put an end to socialist experimentation. Numerous famous architects, who built Romanesque churches in Germany but were no longer commissioned to build in their home countries due to the coming Gothic period, succeeded there; at the same time, the French type of Gothic architecture took root in Bohemia. A number of Italian Renaissance or Baroque architects, painters and sculptors, who crossed the Alps to find new opportunity for creating master works and look for well-paid jobs, were hired by members of Czech nobility and clergy; astonished by the mastery of Czech builders and craftsmen with whom they cooperated, they created wonderful castles and breathtaking Catholic churches. -

Mise En Page 1

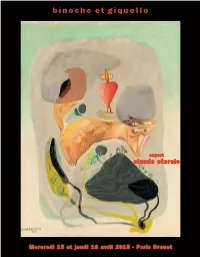

expert claude oterelo Mercredi 15 et jeudi 16 avril 2015 - Paris Drouot MERCREDI 15 AVRIL 2015 À 14H15 du n°1 au n°296 JEUDI 16 AVRIL 2015 À 14H15 du n°297 au n°604 EXPOSITIONS PRIVÉES Étude Binoche et Giquello 5 rue La Boétie - 75008 Paris Jeudi 9 et vendredi 10 avril 2015 de 14h à 18h Tél . +33 1 47 70 48 90 EXPOSITIONS PUBLIQUES Hôtel Drouot - salle 9 Mardi 14 avril 2015 de 11h à 18 heures Mercredi 15 et jeudi 16 avril 2015 de 11h à 12 heures Téléphone pendant l’exposition +33 1 48 00 20 09 AVANT-GARDES DU XXe SIÈCLE ENSEMBLES IMPORTANTS CONCERNANT LA RÉVOLUTION RUSSE, RENÉ CHAR, SALVADOR DALI ÉDITIONS ORIGINALES - LIVRES ILLUSTRÉS - REVUES MANUSCRITS - LETTRES AUTOGRAPHES PHOTOGRAPHIES - DESSINS - TABLEAUX PARIS - HÔTEL DROUOT - SALLE 9 EXPERT Claude OTERELO Membre de la Chambre Nationale des Experts Spécialisés 5, rue La Boétie - 75008 Paris Tél. : +33 6 84 36 35 39 [email protected] assisté de Nicolas Le Bault 5, rue La Boétie - 75008 Paris - tél. +33 (0)1 47 70 48 90 - fax. +33 (0)1 47 42 87 55 [email protected] - www.binocheetgiquello.com Jean-Claude Binoche - Alexandre Giquello - Commissaires-priseurs judiciaires s.v.v. agrément n°2002 389 - Commissaire-priseur habilité pour la vente : Alexandre Giquello JEUDI 16 AVRIL 2015 A 14H15 99 Jeudi 16 avril 2015 14h15 297 297 [ELUARD Paul et Gala]. 2 CARTES DE VISITE. [1917]. 2 x 3,5 cm chacune, sous encadrement. 300/400 € 2 cartes de visite minuscules, la première imprimée Gala, la seconde Paul Eluard. -

The Structural Panel Building in Czechoslovakia Kimberly Elman Zarecor Iowa State University, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Repository @ Iowa State University Architecture Publications Architecture 2010 The Local History of an International Type: The Structural Panel Building in Czechoslovakia Kimberly Elman Zarecor Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/arch_pubs Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, and the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ arch_pubs/44. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Architecture at Digital Repository @ Iowa State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Architecture Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Repository @ Iowa State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Local History of an International Type: The Structural Panel Building in Czechoslovakia Kimberly Elman Zarecor, Iowa State University Abstract: Focusing on the state-run system of architectural offices as a mediator between politics and practice, this article considers how the 1948 Communist Party takeover of Czechoslovakia affected architectural practice and the establishment of housing types in the early 1950s. The legacy of a strong local construction industry before 1948 was critical to these developments. At the new Institute of Prefabricated Buildings, created in 1952, architects and engineers continued earlier research on prefabricated construction technologies. Through this work, the Czechoslovak government and its architectural administration soon concluded that its best long-term option for solving the country’s housing crisis was the use of structural panel construction.