Mapledurham Conservation Area to Give an Overview of the Established Character to Be Preserved and to Identify Possible Areas for Future Enhancement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thames Valley Papists from Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829

Thames Valley Papists From Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829 Tony Hadland Copyright © 1992 & 2004 by Tony Hadland All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without prior permission in writing from the publisher and author. The moral right of Tony Hadland to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 9547547 0 0 First edition published as a hardback by Tony Hadland in 1992. This new edition published in soft cover in April 2004 by The Mapledurham 1997 Trust, Mapledurham HOUSE, Reading, RG4 7TR. Pre-press and design by Tony Hadland E-mail: [email protected] Printed by Antony Rowe Limited, 2 Whittle Drive, Highfield Industrial Estate, Eastbourne, East Sussex, BN23 6QT. E-mail: [email protected] While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, neither the author nor the publisher can be held responsible for any loss or inconvenience arising from errors contained in this work. Feedback from readers on points of accuracy will be welcomed and should be e-mailed to [email protected] or mailed to the author via the publisher. Front cover: Mapledurham House, front elevation. Back cover: Mapledurham House, as seen from the Thames. A high gable end, clad in reflective oyster shells, indicated a safe house for Catholics. -

Themed Cruises

Visit Thames CRUISES The New Orleans, Hobbs of Henley Enjoy a cruise on the River Thames... www.visitthames.co.uk There are so many options for a cruise on the River Thames, you are spoilt for choice. River Thames passenger boat operators offer round trips, stopping or one-way services and can provide all-weather viewing. As well as the scheduled services, you might enjoy a themed cruise. Choose from wildlife watching, party nights or seasonal trips, to name but a few! Packages can include entertainment, food and drink. The main cruising season is April-September but each operator may have sailings outside of this time including special events so please check availability with the business. Cruises are available in London, Windsor, Reading, Henley and Oxford. Here are some great ideas: • River Thames sightseeing cruises from 40 minutes to 2 hours • Music cruises from Jazz and Blues to Tribute nights • Wildlife or picnic cruises • Xmas Party nights or Santa Cruises More information on passenger boat cruises on the River Thames Private Charters are great for special occasions, unforgettable events with family, friends and colleagues, catering from 4- 180. Great ideas for groups too. Visit Thames recommends... www.visitthames.co.uk Hobbs of Henley www.hobbsofhenley.com The Consuta, The Hibernia and the Waterman operate frequent river trips on the Henley Royal Regatta Reach between Marsh Lock and Hambleden Lock with pre- recorded commentary. LOCATION: HENLEY-ON-THAMES City Cruises www.citycruises.com Cruises depart every 30 minutes, every day of the week, all year round from pier locations at Westminster, London Eye, Tower of London and Greenwich. -

South Oxfordshire Emerging Local Plan 2011-2034 Summary and Call for Action

South Oxfordshire Emerging Local Plan 2011-2034 Summary and call for action A Better South Oxfordshire South Oxfordshire Local Plan 2011-2034 South Oxfordshire is part of the Oxfordshire Housing and Growth Deal, along with the other district and county councils in Oxfordshire. In return for a payment of £150m to spend on infrastructure, Oxfordshire has committed to plan for 100,000 new homes in Oxfordshire over the period 2011-2031. To put this in context, there are currently 285,750 homes in Oxfordshire in total South Oxfordshire has committed to build 22,775 homes, far in excess of need, in order to meet the requirements of the Growth Deal. The Plan goes even further than this, proposing sites that will allow the building of 28,465 new homes. Currently there are 58,720 homes in South Oxfordshire, so this is a nearly 50% increase The proposed Oxford-Cambridge Expressway may add another 200,000 to Oxfordshire’s total Why so many – how South Oxfordshire developed the housing NEED Local Authorities have to establish minimum local housing need using the Government’s ‘Standard Method’ - this gives a figure of 556 homes per annum for South Oxfordshire, 12,788 over the plan period (2011-2034) However in 2014 a Strategic Housing Market Assessment (SHMA) was conducted for Oxfordshire, looking at housing required for projected economic growth – this gave a figure of 775 homes per annum, a total of 17,825 over the plan period Oxford City Council signalled it could not meet its own housing need and SODC consider they can take an extra 4,950 homes -

South Oxfordshire Zone Botley 5 ©P1ndar 4 Centre©P1ndart1 ©P1ndar

South_Oxon_Network_Map_South_Oxon_Network_Map 08/10/2014 10:08 Page 1 A 3 4 B4 0 20 A40 44 Oxford A4 B B 4 Botley Rd 4 4017 City 9 South Oxfordshire Zone Botley 5 ©P1ndar 4 Centre©P1ndarT1 ©P1ndar 2 C 4 o T2 w 1 le 4 y T3 A R A o 3 a 4 d Cowley Boundary Points Cumnor Unipart House Templars Ox for Travel beyond these points requires a cityzone or Square d Kenilworth Road Wa Rd tl SmartZone product. Dual zone products are available. ington Village Hall Henwood T3 R Garsington A420 Oxford d A34 Science Park Wootton Sandford-on-Thames C h 4 i 3 s A e Sugworth l h X13 Crescent H a il m d l p A40 X3 to oa R n 4 Radley T2 7 Stadhampton d X2 4 or B xf 35 X39 480 A409 O X1 X40 Berinsfield B 5 A 415 48 0 0 42 Marcham H A Abingdon ig Chalgrove A41 X34 h S 7 Burcot 97 114 T2 t Faringdon 9 X32 d Pyrton 00 7 oa 1 Abingd n R O 67 67A o x 480 B4 8 fo B 0 4 40 Clifton r P 67B 3 d a 45 B rk B A Culham R Sta Hampden o R n 114 T2 a T1 d ford R Rd d w D Dorchester d A4 rayton Rd Berwick Watlington 17 o Warborough 09 Shellingford B Sutton Long Salome 40 Drayton B B Courtenay Wittenham 4 20 67 d 67 Stanford in X1 8 4 oa Little 0 A R 67A The Vale A m Milton Wittenham 40 67A Milton 74 nha F 114 CERTAIN JOURNEYS er 67B a Park r Shillingford F i n 8 3 g Steventon ady 8 e d rove Ewelme 0 L n o A3 45 Fernham a G Benson B n X2 ing L R X2 ulk oa a 97 A RAF Baulking B d Grove Brightwell- 4 Benson ©P1ndar67 ©P1ndar 0 ©P1ndar MON-FRI PEAK 7 Milton Hill 4 67A 1 Didcot Cum-Sotwell Old AND SUNDAYS L Uffington o B 139 n Fa 67B North d 40 A Claypit Lane 4 eading Road d on w 1 -

RFI2793 Your Ref: FOI Request – Chalgrove Masterplan Tel: 0300 1234 500 Email: [email protected]

Date: 15/11/19 Our Ref: RFI2793 Your Ref: FOI Request – Chalgrove Masterplan Tel: 0300 1234 500 Email: [email protected] Windsor House By Email Only Homes England – 6th Floor 50 Victoria Street London SW1H 0TL Dear RE: Request for Information – RFI2793 Thank you for your request of information, which was processed under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA). For clarification, you requested the following information: What relationship does the recent purchase have to the existing Masterplan for Chalgrove Airfield? What is the intended final scale of the Masterplan, given the recent purchase? Is it intended that this additional land will be developed? Are there any changes to the Masterplan that should be communicated to local residents? When will any changes to the Masterplan be communicated to local residents affected by this development? What is the Homes England definition of "Town", and when did the Masterplan that was consulted on change from being one for a Market Village to one for a Market Town? Response We can confirm that we do hold information that falls within the scope of your request, please see below our response. What relationship does the recent purchase have to the existing Masterplan for Chalgrove Airfield? We have bought 189 hectares of land to the north of Chalgrove Airfield to provide flexibility for the high quality housing and employment uses identified in our masterplan. This supports our plans for a new sustainable 21st century market town. What is the intended final scale of the Masterplan, given the recent purchase? Is it intended that this additional land will be developed? Homes England is preparing a planning application for a 3,000 home residential led mixed-use development on the Chalgrove Airfield site which comprises an area of 254hectare in line with the requirements of policy STRAT7 of the South Oxfordshire District Council draft Local Plan 2034. -

Henley-On-Thames Is an Attractive Market Town Set on the River Thames in the Chilterns Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty

HHeennlleeyy--oonn--TThhaammeess TThhee AAccttiioonn PPllaann ffoorr YYeeaarr TThhrreeee 22000066--77 Based upon the Countryside Agency’s Market Town Healthcheck Handbook CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 THE ACTION PLAN 2 CONSULTATION ON PROJECTS 3 HOW TO GET INVOLVED 4 SUMMARY OF YEAR TWO 5 APPENDICES ONE - Strategic Objectives TWO - Action Plan Projects –Short Term & Long Term Henley Action Plan INTRODUCTION Henley-on-Thames is an attractive market town set on the River Thames in the Chilterns Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. With river trade dating back to the 12th century and over 300 buildings designated ‘of special architectural or historical interest’, it is one of the oldest settlements in Oxfordshire. Although known worldwide for its rowing tradition and for hosting the Henley Royal Regatta, the town has much more to offer its visitors, businesses and 10,600 residents throughout the year. That is not to say that the town, like any small market town, is without its challenges. These include traffic and public transport issues, shortage of funding and lack of affordable housing. This Action Plan aims to address some of these issues and to make Henley a better place to work, live in and visit. To achieve this, all parts of the community need to work together –local authorities, residents, the business community and local organisations. Above all, the Plan demonstrates the need for effective partnership. 1 Henley Action Plan THE ACTION PLAN The Henley Action Plan sets out to provide a strategy for improving the town such as maintaining its retail competitiveness, and increasing its community spirit, through various economic, environmental, transport, and social initiatives. -

17 Years and Counting Western Rail Link to Heathrow

t: 0118 946 1800 e: [email protected] insight w: farmeranddyer.com Summer 2018 Bulletin What do men and women want? When analysing the results from its latest Housing Futures survey, a leading nationwide estate agent looked at the differing answers supplied by each sex. When asked to rate their motivations for moving than women, perhaps to enjoy pursuits such house, women listed as important features: as sailing and fishing. Homes with sporting Better schools, broadband connectivity, facilities such as a gym, pool and tennis courts closeness to family and friends, access to public were also more popular with men, while more transport, shops and amenities. women were keen on equestrian amenities. Men on the other hand rated the following as Environmental features appeared to be of more 17 years their top priorities: importance to men than they were to women. Tax changes, retirement, pension support, Code level 5 ratings, renewable energy, living and counting political environment, mobile coverage. walls, grey/potable water and green roofs were all markedly more popular with male At the start of June, the staff of Farmer When it came to dream home items, the survey respondents. & Dyer were in joyous mood as they revealed that 14% of men wanted a cinema/ celebrated its 17th birthday. We have screening room and 12% wanted a wine cellar. Both genders place personal finances as moved thousands of clients since that day In contrast, 24% of women rated an AGA oven important which reflects both the capital as their top home accessory, while 18% wanted growth of the last 30 years from residential and as we seem to say every year ‘time a kitchen island. -

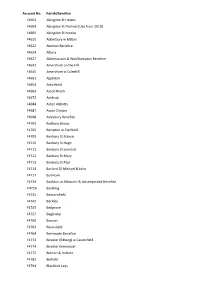

List of Fee Account

Account No. Parish/Benefice F4603 Abingdon St Helens F4604 Abingdon St Michael (Use from 2019) F4605 Abingdon St Nicolas F4610 Adderbury w Milton F4622 Akeman Benefice F4624 Albury F4627 Aldermaston & Woolhampton Benefice F4642 Amersham on the Hill F4645 Amersham w Coleshill F4651 Appleton F4654 Arborfield F4663 Ascot Heath F4672 Ashbury F4684 Aston Abbotts F4687 Aston Clinton F4698 Aylesbury Benefice F4703 Badbury Group F4705 Bampton w Clanfield F4709 Banbury St Francis F4710 Banbury St Hugh F4711 Banbury St Leonard F4712 Banbury St Mary F4713 Banbury St Paul F4714 Barford SS Michael & John F4717 Barkham F4724 Basildon w Aldworth & Ashampstead Benefice F4726 Baulking F4735 Beaconsfield F4742 Beckley F4745 Bedgrove F4757 Begbroke F4760 Benson F4763 Berinsfield F4764 Bernwode Benefice F4773 Bicester (Edburg) w Caversfield F4774 Bicester Emmanuel F4775 Bierton & Hulcott F4782 Binfield F4794 Blackbird Leys F4797 Bladon F4803 Bledlow w Saunderton & Horsenden F4809 Bletchley F4815 Bloxham Benefice F4821 Bodicote F4836 Bracknell Team Ministry F4843 Bradfield & Stanford Dingley F4845 Bray w Braywood F6479 Britwell F4866 Brize Norton F4872 Broughton F4875 Broughton w North Newington F4881 Buckingham Benefice F4885 Buckland F4888 Bucklebury F4891 Bucknell F4893 Burchetts Green Benefice F4894 Burford Benefice F4897 Burghfield F4900 Burnham F4915 Carterton F4934 Caversham Park F4931 Caversham St Andrew F4928 Caversham Thameside & Mapledurham Benefice F4936 Chalfont St Giles F4939 Chalfont St Peter F4945 Chalgrove w Berrick Salome F4947 Charlbury -

THE RIVER THAMES a Complete Guide to Boating Holidays on the UK’S Most Famous River the River Thames a COMPLETE GUIDE

THE RIVER THAMES A complete guide to boating holidays on the UK’s most famous river The River Thames A COMPLETE GUIDE And there’s even more! Over 70 pages of inspiration There’s so much to see and do on the Thames, we simply can’t fit everything in to one guide. 6 - 7 Benson or Chertsey? WINING AND DINING So, to discover even more and Which base to choose 56 - 59 Eating out to find further details about the 60 Gastropubs sights and attractions already SO MUCH TO SEE AND DISCOVER 61 - 63 Fine dining featured here, visit us at 8 - 11 Oxford leboat.co.uk/thames 12 - 15 Windsor & Eton THE PRACTICALITIES OF BOATING 16 - 19 Houses & gardens 64 - 65 Our boats 20 - 21 Cliveden 66 - 67 Mooring and marinas 22 - 23 Hampton Court 68 - 69 Locks 24 - 27 Small towns and villages 70 - 71 Our illustrated map – plan your trip 28 - 29 The Runnymede memorials 72 Fuel, water and waste 30 - 33 London 73 Rules and boating etiquette 74 River conditions SOMETHING FOR EVERY INTEREST 34 - 35 Did you know? 36 - 41 Family fun 42 - 43 Birdlife 44 - 45 Parks 46 - 47 Shopping Where memories are made… 48 - 49 Horse racing & horse riding With over 40 years of experience, Le Boat prides itself on the range and 50 - 51 Fishing quality of our boats and the service we provide – it’s what sets us apart The Thames at your fingertips 52 - 53 Golf from the rest and ensures you enjoy a comfortable and hassle free Download our app to explore the 54 - 55 Something for him break. -

Crossways Dorchester-On-Thames F Oxfordshire

CROSSWAYS www.warmingham.com DORCHESTER-ON-THAMES F OXFORDSHIRE CROSSWAYS DORCHESTER-ON-THAMES F OXFORDSHIRE Oxford - 9 miles F Wallingford - 4.5 miles F Abingdon - 5.5 miles F Culham Station - 3.9 miles F Didcot/Mainline Station for London Paddington - 6.5 miles F Goring on Thames - 10.4 miles F Oxford Tube Coach connection to London at Lewknor - 11 miles (Distances approximate) Located to the South of Oxford on the River Thames, in the heart of this this historic village with its impressive Abbey and excellent road and nearby rail connections. Situated opposite the village recreation ground with playground and tennis courts. A characterful detached village house dating from the 17th Century, presented beautifully with contemporary yet traditional décor, with 4-5 bedroom accommodation, 3 reception rooms, a delightful South facing walled garden private gated driveway and detached garage. F Reception Hall F Study F Sitting Room with Inglenook Fireplace & Wood Burning Stove F Garden Room SITUATION The Thameside village of Dorchester-on-Thames has a long history dating back to Neolithic times with evidence locally of Bronze and Iron Age Settlements including Dyke Hills a rare example of a pre-Roman town. F Kitchen/Dining Room with Aga and French doors to Garden Dorchester’s proximity to the navigable Thames and being bounded on 3 sides by water made it ideally suited and strategic for both F Utility Room communication and defence. The present village extends over the old Romano walled town of which the Southern and Western boundaries can still be traced. Later the F Vaulted Master Bedroom with En-Suite Bathroom town become the centre of a Saxon settlement. -

Situation of Polling Stations Police and Crime Commissioner Election

Police and Crime Commissioner Election Situation of polling stations Police area name: Thames Valley Voting area name: South Oxfordshire No. of polling Situation of polling station Description of persons entitled station to vote S1 Benson Youth Hall, Oxford Road, Benson LAA-1, LAA-1647/1 S2 Benson Youth Hall, Oxford Road, Benson LAA-7, LAA-3320 S3 Crowmarsh Gifford Village Hall, 6 Benson Lane, LAB1-1, LAB1-1020 Crowmarsh Gifford, Wallingford S4 North Stoke Village Hall, The Street, North LAB2-1, LAB2-314 Stoke S5 Ewelme Watercress Centre, The Street, LAC-1, LAC-710 Ewelme, Wallingford S6 St Laurence Hall, Thame Road, Warborough, LAD-1, LAD-772 Wallingford S7 Berinsfield Church Hall, Wimblestraw Road, LBA-1, LBA-1958 Berinsfield S8 Dorchester Village Hall, 7 Queen Street, LBB-1, LBB-844 Dorchester, Oxon S9 Drayton St Leonard Village Hall, Ford Lane, LBC-1, LBC-219 Drayton St Leonard S10 Berrick and Roke Village Hall, Cow Pool, LCA-1, LCA-272 Berrick Salome S10A Berrick and Roke Village Hall, Cow Pool, LCD-1, LCD-86 Berrick Salome S11 Brightwell Baldwin Village Hall, Brightwell LCB-1, LCB-159 Baldwin, Watlington, Oxon S12 Chalgrove Village Hall, Baronshurst Drive, LCC-1, LCC-1081 Chalgrove, Oxford S13 Chalgrove Village Hall, Baronshurst Drive, LCC-1082, LCC-2208 Chalgrove, Oxford S14 Kingston Blount Village Hall, Bakers Piece, LDA-1 to LDA-671 Kingston Blount S14 Kingston Blount Village Hall, Bakers Piece, LDC-1 to LDC-98 Kingston Blount S15 Chinnor Village Hall, Chinnor, Church Road, LDB-1971 to LDB-3826 Chinnor S16 Chinnor Village Hall, -

A Transport Service for Disabled and Mobility- Impaired People

Oxfordshire Dial-a-Ride 0845 310 11 11 A transport service for disabled and mobility- impaired people operated by With financial support from What is Dial-a-Ride? Oxfordshire Dial-a-Ride is a door-to-door transport service for those who are unable to use or who find it difficult to use conventional public transport, such as elderly or disabled people. The drivers of the vehicles are specially trained in the assistance of wheelchair users and those with mobility problems. Where can I go? Whatever your journey purpose*, Dial-a-Ride is available to take you! *The only exception is for journeys to hospitals for appointments. Please speak to your doctor about travel schemes to enable you to make your appointment . How do I qualify to use Oxfordshire Dial-a-Ride? • You must be resident in Oxfordshire. • You can use Dial-a-Ride if you have a mobility or other condition which means that you cannot use, or find it difficult to use, conventional public transport. You don’t have to be registered disabled or be a wheelchair-user. For example, you might be unable to walk to the bus stop. • Age and nature of disability are irrelevant. Advantages of using Oxfordshire Dial-a-Ride When and where can I travel? The service is available between 9:00am and 5:00pm as follows: We want to make sure that the Dial-a-Ride service is available to as many members as possible, as fairly as possible, every day it operates. However, due to high demand, and to make best use of the buses, we serve certain areas on set days, allocating places to customers to travel on the day when the bus is in their area.