Heritage Research Matters. Case Studies of Research Impact Contributing to Sustainable Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iaea Tecdoc Series Tecdoc Iaea @

IAEA-TECDOC-1803 IAEA-TECDOC-1803 IAEA TECDOC SERIES Trends of Synchrotron Radiation Applications in Cultural Heritage, Forensics and Materials Science Forensics Applications in Cultural Heritage, of Synchrotron Radiation Trends IAEA-TECDOC-1803 Trends of Synchrotron Radiation Applications in Cultural Heritage, Forensics and Materials Science @ TRENDS OF SYNCHROTRON RADIATION APPLICATIONS IN CULTURAL HERITAGE, FORENSICS AND MATERIALS SCIENCE The following States are Members of the International Atomic Energy Agency: AFGHANISTAN GEORGIA OMAN ALBANIA GERMANY PAKISTAN ALGERIA GHANA PALAU ANGOLA GREECE PANAMA ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA GUATEMALA PAPUA NEW GUINEA ARGENTINA GUYANA PARAGUAY ARMENIA HAITI PERU AUSTRALIA HOLY SEE PHILIPPINES AUSTRIA HONDURAS POLAND AZERBAIJAN HUNGARY PORTUGAL BAHAMAS ICELAND QATAR BAHRAIN INDIA REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA BANGLADESH INDONESIA ROMANIA BARBADOS IRAN, ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF RUSSIAN FEDERATION BELARUS IRAQ RWANDA BELGIUM IRELAND SAN MARINO BELIZE ISRAEL SAUDI ARABIA BENIN ITALY SENEGAL BOLIVIA, PLURINATIONAL JAMAICA SERBIA STATE OF JAPAN SEYCHELLES BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA JORDAN SIERRA LEONE BOTSWANA KAZAKHSTAN SINGAPORE BRAZIL KENYA SLOVAKIA BRUNEI DARUSSALAM KOREA, REPUBLIC OF SLOVENIA BULGARIA KUWAIT SOUTH AFRICA BURKINA FASO KYRGYZSTAN SPAIN BURUNDI LAO PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC SRI LANKA CAMBODIA REPUBLIC SUDAN CAMEROON LATVIA SWAZILAND CANADA LEBANON SWEDEN CENTRAL AFRICAN LESOTHO SWITZERLAND REPUBLIC LIBERIA SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC CHAD LIBYA TAJIKISTAN CHILE LIECHTENSTEIN THAILAND CHINA LITHUANIA THE FORMER YUGOSLAV -

A Research on the Representation of Turkish National Identity: Buildings Abroad

A RESEARCH ON THE REPRESENTATION OF TURKISH NATIONAL IDENTITY: BUILDINGS ABROAD A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF NATURAL AND APPLIED SCIENCES OF THE MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY M. HALUK ZELEF IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE SEPTEMBER 2003 Approval of the Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences __________________________ Prof. Dr. Canan Özgen Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy __________________________ Assoc. Prof. Dr. Selahattin Önür Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. __________________________ Assoc. Prof. Dr. Selahattin Önür Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Bozkurt Güvenç ___________________________ Prof. Dr. Haluk Pamir ___________________________ Prof. Dr. Yıldırım Yavuz ___________________________ Assoc. Prof. Dr. Aydan Balamir ___________________________ Assoc. Prof. Dr. Selahattin Önür ___________________________ ABSTRACT A RESEARCH ON THE REPRESENTATION OF TURKISH IDENTITY BUILDINGS ABROAD Zelef, M. Haluk Ph.D., Department of Architecture Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Selahattin Önür September 2003, 264 pages This thesis is the result of an attempt to record, classify and develop an understanding of the motivations and dynamics in the design and realization of the buildings -

Spectator Guide

spectator guide Information in this guide is correct as of the date of publication. The Foundation "Directorate of the 2nd European Games 2019" may update and supplement this version. For more information go to www.minsk2019.by CULTURAL OLYMPIAD CULTURAL 2nd EUROPEAN GAMES MINSK 2019 01. GREETINGS 02. FLAME OF PEACE 03. SPORTS 04. COMPETITION SCHEDULE 1-1 HI, FRIENDS! I am Lesik, mascot of the 2nd European Games MINSK 2019. I invite you to Minsk to the main European sports celebration in 2019! MINSK 2019 will bring together the finest athletes to promote Olympic values and unite all nations of Europe in a fair contest. The Games will be a mix of the centuries-old Belarusian culture and ideals of the sporting movement. I have prepared a lot of nice bright vytsinankas for the Games. Vytsynanka is the traditional Belarusian paper craft which has been chosen as a symbol of GREETINGS the Games. The 2nd European Games logo is a colourful fern flower. Legends tell that the fern flower blossoms on the summer night of Ivan Kupala. The lucky ones to find it will have all their dreams come true. Athletes from all over Europe will gather in Minsk in June 2019 to follow their dreams and compete for the priceless trophy. It is not only triumphs, record-breaking results and splendid shows that make this celebration bright – but your smiles, too. MINSK 2019 is for everyone! Your emotions will breathe life into the stadiums and sports arenas. Your support will encourage the best athletes of Europe to be faster, stronger and higher. -

E-Readiness Assessment Report

The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) for the Information for Development Program (infoDev) National Academy of Sciences of Belarus Belarusian Fund of Informatization ICT Infrastructure and E-Readiness Assessments in the Republic of Belarus Grant # ICT 015 E-Readiness Assessment Report April 2003 Minsk LIST OF RESEARCHERS 1. Victor I. Dravitsa, Contact Person of the Grant – Belarusian Fund of Informatization 2. Uladzimir V. Anishchanka Deputy Contact Person, Coordinating Group executive – United Institute of Informatics Problems, National Academy of Sciences of Belarus 3. Vladimir V. Basko – IT Companies Association 4. Yury I. Vorotnitsky – Belarusian State University 5. Sergey V. Yenin – NGO “Information Society” 6. Yuriy A. Zisser – TUT.BY Belarusian Portal (Reliable Software Co.) 7. Alexander N. Gorbach – State Center of Information Security 8. Valery E. Kratenok – Ministry of Health 9. Leonid V. Semenenko – Institute of Applied Physical Problems 10. Oleg I. Tavgen – Academy after Degree Education 11. Vladimir A. Labunov – Belarusian State University of Informatics and Radio Electronics 12. Nikolay I. Listopad – Ministry of Education 13. Alexander N. Kurbatsky – Association “National Infopark” 14. Gennadiy P. Chepurny – Ministry of Economics 15. Boris N. Panshin – National Centre of Marketing and Price Study 16. Michael M. Makhaniok – National Centre of Information Resources & Technologies, National Academy of Sciences of Belarus 17. Artour I. Savitsky – Belarusian Fund of Informatization 18. Ivan A. Korol – Ministry of Labour and Social Assurances 19. Anatoly L. Rodtsevich – Ministry of Industry 20. Anatoly N. Morozevich – High Attestation Committee 21. Michael M. Kovalev – National Bank 22. Oleg F. Seklitsky – RA “Beltelecom” 23. Oleg T. Manaev – Independent Institute of Socio-Economic & Political Studies in Minsk, Belarus 24. -

Proceedings Book

PROCEEDINGS BOOK 5th International Conference on New Trends in Architecture and Interior Design APRIL 26-28, 2019 Istanbul/Turkey http://www.icntadconference.com/ 2 ICNTAD’2019 5th International Conference on New Trends in Architecture and Interior Design Istanbul/Turkey Published by the ICNTAD Secretariat Editors: Prof. Dr. Burçin Cem Arabacıoğlu ICNTAD Secretariat Büyükdere Cad. Ecza sok. Pol Center 4/1 Levent-İstanbul E-mail: [email protected]@gmail.com http://www.icntadconference.com ISBN: 978-605-66506-7-3 Conference organised in collaboration with Smolny Institute of the Russian Academy of Education Copyright @ 2019 AIOCICNTAD and Authors All Rights Reserved No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying , recording or by any storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the copyrights owners. 3 SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Prof. Dr. Barbara Camocini Polytechnic University of Milan – Italy Prof. Dr. Birgül Çolakoğlu İstanbul Technical University – Turkey Prof. Dr. Burçin Cem Arabacıoğlu Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University – Turkey Prof. Dr. Çiğdem Polatoğlu Yıldız Technical University – Turkey Prof. Dr. Demet Binan Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University – Turkey Prof. Dr. Deniz İncedayı Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University – Turkey Prof. Dr. Didem Baş Yanarateş İstanbul Arel University – Turkey Prof. Dr. Füsun Seçer Kariptaş Haliç University – Turkey Prof. Dr. Gül Koçlar Oral İstanbul Technical University – Turkey Prof. Dr. Gülay Zorer Gedik Yıldız Technical University – Turkey Prof. Dr. Gülay Usta İstanbul Kültür University – Turkey Prof. Dr. Gülşen Özaydın Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University – Turkey Prof Dr. İnci Deniz Ilgın Marmara University – Turkey Prof. -

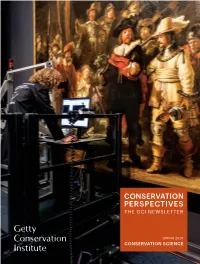

CONSERVATION PERSPECTIVES the Gci Newsletter

CONSERVATION PERSPECTIVES THE GCI NEWSLETTER SPRING 2020 CONSERVATION SCIENCE A Note from As this issue of Conservation Perspectives was being prepared, the world confronted the spread of coronavirus COVID-19, threatening the health and well-being of people across the globe. In mid-March, offices at the Getty the Director closed, as did businesses and institutions throughout California a few days later. Getty Conservation Institute staff began working from home, continuing—to the degree possible—to connect and engage with our conservation colleagues, without whose efforts we could not accomplish our own work. As we endeavor to carry on, all of us at the GCI hope that you, your family, and your friends, are healthy and well. What is abundantly clear as humanity navigates its way through this extraordinary and universal challenge is our critical reliance on science to guide us. Science seeks to provide the evidence upon which we can, collectively, make decisions on how best to protect ourselves. Science is essential. This, of course, is true in efforts to conserve and protect cultural heritage. For us at the GCI, the integration of art and science is embedded in our institutional DNA. From our earliest days, scientific research in the service of conservation has been a substantial component of our work, which has included improving under- standing of how heritage was created and how it has altered over time, as well as developing effective conservation strategies to preserve it for the future. For over three decades, GCI scientists have sought to harness advances in science and technology Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI Anna Flavin, Photo: to further our ability to preserve cultural heritage. -

Across the Borders

Contact information: Conference East European Warsaw mail: [email protected] Skype: weec.sta Facebook: Weec Sew UW Internet Registration: www.studium.uw.edu.pl/weec Information: www.uw.edu.pl link: Conferences The Conference Headquarters are located at: The Centre for East European Studies The Conference O ce 7/55 Oboźna str., entrance from Sewerynów street PL 00-927 Warszawa phone no (0-48) 22-55-21-888 fax no (0-48) 22-55-21-887 media: Across the Borders partners: Organized by: Programme Studium Europy Wschodniej – Uniwersytet Warszawski Pałac Potockich, Krakowskie Przedmieście 26/28 00-927 Warszawa University of Warsaw phone no (0-48) 22-55-22-555 fax no (0-48) 22-55-22-222 2013 July 15-18, 2013 mail: [email protected] www.studium.uw.edu.pl Warsaw, Poland 000 + Okladka 2013_CS55.indd 41 7/8/13 12:48 PM TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Foreword from Prof. Alojzy Z. Nowak, Ph.D. Vice-Rector for Research and Liaison .......................3 2. Foreword from Jan Malicki, Conference Director ................................................................................................4 3. Conference organizing Board and Staff ....................................................................................................................6 4. Panel Grid .....................................................................................................................................................................................8 5. MONDAY Grid .........................................................................................................................................................................14 -

Central Banks Or Single Financial Authorities? Economics, Politics and Law

PRELIMINARY DRAFT : DECEMBER, 16, 2003 CENTRAL BANKS OR SINGLE FINANCIAL AUTHORITIES? ECONOMICS, POLITICS AND LAW Donato Masciandaro¨ ABSTRACT The objective of this work is to offer a political delegation approach for the analysis of the financial supervision architectures. Focusing on the key issue in the debate on financial supervision structure – single authority versus multi-authorities model – the paper claims that the optimal degree of concentration in the financial supervision regime cannot be defined a priori; rather it is an expected variable, calculated by the policymakers that maintains or reform the financial architecture. Therefore the adopted approach is to consider the supervisory structure with one or more authorities as an endogenous variable, determined in turn by the dynamics of other structural variables, economic and institutional, that can explain the political delegation process. In order to construct this endogenous variable, it is first introduced a Financial Authorities’ Concentration Index (FAC Index). The comparative analysis of 69 countries, based on this indicator, showed that an increase in the degree of concentration was evident in the developed countries, and particularly in the European Union. Then, in order to consider the nature of the institutions involved in the control responsibilities – i.e. what role the central bank plays - it is introduced an index of the central bank's involvement in financial supervision, the Central Bank as Financial Authority Index (CBFA Index). Each national regime can be identified with the two above characteristics. Two the most frequent models: countries with a high concentration of powers with low central bank involvement (Single Financial Authority Regime); countries with a low concentration of powers with high central bank involvement (Central Bank Dominated Multiple Supervisors Regime). -

Sacred Places Europe: 108 Destinations

Reviews from Sacred Places Around the World “… the ruins, mountains, sanctuaries, lost cities, and pilgrimage routes held sacred around the world.” (Book Passage 1/2000) “For each site, Brad Olsen provides historical background, a description of the site and its special features, and directions for getting there.” (Theology Digest Summer, 2000) “(Readers) will thrill to the wonderful history and the vibrations of the world’s sacred healing places.” (East & West 2/2000) “Sites that emanate the energy of sacred spots.” (The Sunday Times 1/2000) “Sacred sites (to) the ruins, sanctuaries, mountains, lost cities, temples, and pilgrimage routes of ancient civilizations.” (San Francisco Chronicle 1/2000) “Many sacred places are now bustling tourist and pilgrimage desti- nations. But no crowd or souvenir shop can stand in the way of a traveler with great intentions and zero expectations.” (Spirituality & Health Summer, 2000) “Unleash your imagination by going on a mystical journey. Brad Olsen gives his take on some of the most amazing and unexplained spots on the globe — including the underwater ruins of Bimini, which seems to point the way to the Lost City of Atlantis. You can choose to take an armchair pilgrimage (the book is a fascinating read) or follow his tips on how to travel to these powerful sites yourself.” (Mode 7/2000) “Should you be inspired to make a pilgrimage of your own, you might want to pick up a copy of Brad Olsen’s guide to the world’s sacred places. Olsen’s marvelous drawings and mysterious maps enhance a package that is as bizarre as it is wonderfully acces- sible. -

SYNCHROTRON RADIATION in ART, ARCHAEOLOGY and CULTURAL HERITAGE SCIENCE Dipartimento Di Fisica E Di Scienze Della Terra Univers

SYNCHROTRON RADIATION IN ART, ARCHAEOLOGY AND CULTURAL HERITAGE SCIENCE Dipartimento di Fisica e di Scienze della Terra Università di Messina Viale Ferdinando Stagno d’Alcontres 98166 Messina S. Agata, Italy Abstract The scientific investigations aimed to the study, characterization and conservation of archaeological and artistic finds are in general based on a strong interdisciplinary approach, which implies the collaboration among scientists and archaeologists expert in many different fields. The knowledge transfer between different research groups is in particular required by the considerable amount of different conventional and advanced techniques which can be applied to ancient materials. This requires that researchers have specific technical and scientific background. One of the main requirement imposed by the archaeologists in the studies of ancient and precious materials is that the selected techniques must be non-destructive (or at most micro-destructive). In this scenario, synchrotron radiation-based methods can play a central role, being specifically suitable for micro-non-destructive analyses. The objective of this lesson is to show how synchrotron radiation-based experiments, employing highly brilliant and collimated micro-beams of X-rays can be exploited in diffractometric, spectroscopic and imaging investigations of archaeological and artistic objects, obtaining results with unprecedented space and energy resolution. Introduction The application of synchrotron radiation (SR) in archaeological and cultural heritage (CH) science is relatively recent, dating to the end of ’80s, and it became wide spread only in the last years, thanks to a more continuous dialog between archaeologists and experts of the physical and chemical techniques based on the use of SR and neutrons. This welcome development is mainly due to the fact that, for many reasons, SR is a very suitable and powerful tool in the investigations of very rare and fragile objects, on which no damages must be induced and only non-destructive analyses are allowed. -

Virtual Restoration and Virtual Reconstruction in Cultural Heritage: Terminology, Methodologies, Visual Representation Techniques and Cognitive Models

information Article Virtual Restoration and Virtual Reconstruction in Cultural Heritage: Terminology, Methodologies, Visual Representation Techniques and Cognitive Models Eva Pietroni * and Daniele Ferdani CNR, Institute of Heritage Science, Research Area Rome 1, Via Salaria Km 29,300, Monterotondo St., 00015 Rome, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-06-9067-2721 Abstract: Today, the practice of making digital replicas of artworks and restoring and recontex- tualizing them within artificial simulations is widespread in the virtual heritage domain. Virtual reconstructions have achieved results of great realistic and aesthetic impact. Alongside the practice, a growing methodological awareness has developed of the extent to which, and how, it is permissible to virtually operate in the field of restoration, avoid a false sense of reality, and preserve the reliability of the original content. However, there is not yet a full sharing of meanings in virtual restoration and reconstruction domains. Therefore, this article aims to clarify and define concepts, functions, fields of application, and methodologies. The goal of virtual heritage is not only producing digital replicas. In the absence of materiality, what emerges as a fundamental value are the interaction processes, the semantic values that can be attributed to the model itself. The cognitive process originates from this interaction. The theoretical discussion is supported by exemplar case studies carried out by the authors over almost twenty years. Finally, the concepts of uniqueness and authenticity need Citation: Pietroni, E.; Ferdani, D. Virtual Restoration and Virtual to be again pondered in light of the digital era. Indeed, real and virtual should be considered as a Reconstruction in Cultural Heritage: continuum, as they exchange information favoring new processes of interaction and critical thinking. -

Analysis of Diagnostic Images of Artworks and Feature Extraction: Design of a Methodology

Journal of Imaging Article Analysis of Diagnostic Images of Artworks and Feature Extraction: Design of a Methodology Annamaria Amura 1,*, Alessandro Aldini 1 , Stefano Pagnotta 2 , Emanuele Salerno 3 , Anna Tonazzini 3 and Paolo Triolo 4 1 Department of Pure and Applied Sciences, University of Urbino Carlo Bo, 61029 Urbino, Italy; [email protected] 2 Department of Earth Sciences, University of Pisa, 56126 Pisa, Italy; [email protected] 3 National Research Council of Italy, Institute of Information Science and Technologies, 56124 Pisa, Italy; [email protected] (E.S.); [email protected] (A.T.) 4 Department of Earth Sciences of the Environment and Life, Methodologies for Conservation and Restoration of Cultural Heritage, University of Genoa, 16126 Genova, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Digital images represent the primary tool for diagnostics and documentation of the state of preservation of artifacts. Today the interpretive filters that allow one to characterize information and communicate it are extremely subjective. Our research goal is to study a quantitative analysis method- ology to facilitate and semi-automate the recognition and polygonization of areas corresponding to the characteristics searched. To this end, several algorithms have been tested that allow for separating the characteristics and creating binary masks to be statistically analyzed and polygonized. Since our methodology aims to offer a conservator-restorer model to obtain useful graphic documentation in a short time that is usable for design and statistical purposes, this process has been implemented in a Citation: Amura, A.; Aldini, A.; single Geographic Information Systems (GIS) application.