Adolescent Girls' Capabilities in Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kathmandu - Bhaktapur 0 0 0 0 5 5

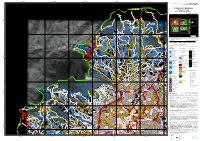

85°12'0"E 85°14'0"E 85°16'0"E 85°18'0"E 85°20'0"E 322500 325000 327500 330000 332500 335000 337500 GLIDE number: N/A Activation ID: EMSN012 Product N.: Reference - A1 NEPAL, v2 Kathmandu - Bhaktapur 0 0 0 0 5 5 7 7 Reference map 7 7 0 0 3 3 2014 - Detail 25k Sheet A1 Production Date: 18/07/2014 N " 0 ' n 8 4 N ° E " !Gonggabu 7 E ú A1 A2 A3 0 2 E E ' 8 E !Jorpati 4 ! B Jhormahankal ° ! n ú B !Kathmandu 7 ! B n 2 !Kirtipur n Madhy! apur Sangla ú !Bhaktapur ú ú ú n ú B1 B2 ú n ! B ! ú B 0 0 0 0 0 n Kabhresthali n 0 5 5 7 7 0 0 3 3 0 5 10 km /" n n ú ú ú n ú n n n Cartographic Information ! ! B B ! B ú ! B ! n B 1:25000 Full color A1, low resolution (100 dpi) ! WX B ! ú B n Meters n ú ú 0 n n 10000 n 20000 30000 40000 50000 XY ! B ú ú Grid: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 45N map coordinate system ni t ! ú B a ! Jitpurphedi ú B Tick Marks: WGS 84 geographical coordinate system ú i n m d n u a ICn n n N n h ! B ! B Legend s ! B i ! B ! n B ! B ! B B ! B n n n ! n B n TokhaChandeswori Hydrography Transportation Urban Areas úú n ! B ! B ! Crossing Point (<500m) Built Up Area n RB iver Line (500>=nm) ! B ! ! B B ! B ú ! ! B B ú n ! ú B WXWX Intermittent Bridge Point Agricultural ! B ! B ! B ! ! ú B B Penrennial WX Culvert Commercial ! B ú ú n River Area (>=1Ha) XY n Ford Educational N n ! B " n n n n n Intermittent Crossing Line (>=500m) Industrial 0 ! B ' n ! ! B B 6 ! B IC ! B Perennial Bridge 4 0 n 0 Institutional N ° E 0 n 0 n E " 7 5 ú Futung ú n5 ! Reservoir Point (<1Ha) B 2 2 0 2 E Culvert ' Medical 7 E 7 6 0 n E 0 õö 3 ú 3 IC 4 Reservoir Point -

Tables Table 1.3.2 Typical Geological Sections

Tables Table 1.3.2 Typical Geological Sections - T 1 - Table 2.3.3 Actual ID No. List of Municipal Wards and VDC Sr. No. ID-No. District Name Sr. No. ID-No. District Name Sr. No. ID-No. District Name 1 11011 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.1 73 10191 Kathmandu Gagalphedi 145 20131 Lalitpur Harisiddhi 2 11021 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.2 74 10201 Kathmandu Gokarneshwar 146 20141 Lalitpur Imadol 3 11031 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.3 75 10211 Kathmandu Goldhunga 147 20151 Lalitpur Jharuwarasi 4 11041 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.4 76 10221 Kathmandu Gongabu 148 20161 Lalitpur Khokana 5 11051 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.5 77 10231 Kathmandu Gothatar 149 20171 Lalitpur Lamatar 6 11061 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.6 78 10241 Kathmandu Ichankhu Narayan 150 20181 Lalitpur Lele 7 11071 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.7 79 10251 Kathmandu Indrayani 151 20191 Lalitpur Lubhu 8 11081 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.8 80 10261 Kathmandu Jhor Mahakal 152 20201 Lalitpur Nallu 9 11091 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.9 81 10271 Kathmandu Jitpurphedi 153 20211 Lalitpur Sainbu 10 11101 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.10 82 10281 Kathmandu Jorpati 154 20221 Lalitpur Siddhipur 11 11111 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.11 83 10291 Kathmandu Kabresthali 155 20231 Lalitpur Sunakothi 12 11121 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.12 84 10301 Kathmandu Kapan 156 20241 Lalitpur Thaiba 13 11131 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.13 85 10311 Kathmandu Khadka Bhadrakali 157 20251 Lalitpur Thecho 14 11141 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.14 86 10321 Kathmandu Lapsephedi 158 20261 Lalitpur Tikathali 15 11151 Kathmandu -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

In the Name of 'Empowerment': Women and Development in Urban Nepal

In the name of ‘empowerment’: women and development in urban Nepal Margaret Becker Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy Department of Anthropology School of Social Sciences, Faculty of Arts The University of Adelaide December 2016 Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................... v Thesis declaration ...................................................................................................... vi Acknowledgements .................................................................................................. vii Transliteration ........................................................................................................... ix List of acronyms and abbreviations ........................................................................... x Introduction ...................................................................................................... 1 Ethnographic locations and methodology .................................................................. 3 Situating the organisations ......................................................................................... 5 Critical perspectives on development ........................................................................ 8 Critical perspectives on empowerment .................................................................... 12 Reflections on empowerment ................................................................................... 18 The structure -

NEPAL: Kathmandu - Operational Presence Map (As of 30 Jun 2015)

NEPAL: Kathmandu - Operational Presence Map (as of 30 Jun 2015) As of 30 June 2015, 110 organizations are reported to be working in Kathmandu district Number of organizations per cluster Health Shelter NUMBER OF ORGANI WASH Protection Protection Education Nutrition 22 5 1 20 20 40 ZATIONS PER VDC No. of Org Gorkha Health No data Dhading Rasuwa 1 Nuwakot 2 - 4 Makawanpur Shelter 5 - 7 8 - 18 Sindhupalchok INDIA CHINA Kabhrepalanchok No. of Org Dolakha Sindhuli Ramechhap Education No data 1 No. of Org Okhaldunga 2 - 10 WASH 11- 15 No data 16 - 40 1 - 2 Creation date: Glide number: Sources: 3 - 4 The boundaries and names shown and the desi 4 - 5 No. of Org 10 July 20156 EQ-2015-000048-NPL- 8 Cluster reporting No data No. of Org 1 2 Nutrition gnations used on this map do not imply offici 3 No data 4 1 2 - 5 6 - 10 11 - 13 al endorsement or acceptance by the Uni No. of Org Feedback: No data [email protected] www.humanitarianresponse.info1 2 ted Nations. 3 4 Kathmandu District List of organizations by VDC and cluster Health Protection Shelter and NFI WASH Nutrition Edaucation VDC name Alapot UNICEF,WHO Caritas Nepal,HDRVG SDPC Restless Badbhanjyang UNICEF,WHO HDRVG OXFAM SDPC Restless Sangkhu Bajrayogini HERD,UNICEF,WHO IRW,MC IMC,OXFAM SDPC NSET Balambu UNICEF,WHO GIZ,LWF IMC UNICEF,WHO DCWB,Women for Human Rights Caritas Nepal RMSO,Child NGO Foundation Baluwa Bhadrabas UNICEF,WHO SDPC Bhimdhunga UNICEF,WHO WV NRCS,WV SDPC Restless JANTRA,UNICEF,WHO,CIVCT Nepal DCWB,CIVCT Nepal,CWISH,The Child NGO Foundation,GIZ,Global SDPC Restless Himalayan Innovative Society Medic,NRCS,RMSO Budhanilkantha UNICEF,WHO ADRA,AWO International e. -

Vegetation and Climate Around 780 Kyrs BP in Northern Kathmandu Valley, Central Nepal

Bulletin of Department of Geology, TribhuvanVegetation University, and climate Kathmandu, around 780 Nepal, kyrs BP vol. in 20-21, northern 2018, Kathmandu pp. 37-48. valley, central Nepal Vegetation and climate around 780 kyrs BP in northern Kathmandu valley, central Nepal *Sima Humagain and Khum N. Paudayal Central Department of Geology, Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal ABSTRACT Palynological study from the Dharmasthali Formation exposed in the northern part of Kathmandu valley revealed the composition of forest vegetation that were growing in middle Pleistocene (780 kyrs BP) in this area. In a total fifteen samples were collected from the 46 m exposed section for the palynological study. The profile can be divided into two zones on the basis of pollen assemblages. The lower part (DF-I) is dominated by Pteridophyte spores such as Lygodium, Polypodium, Cyathea and Pteris. The dominance of Pteridophytes indicate that the forest floor was moist and humid. The tree pollen consists of Abies, Pinus, Quercus, Podocarpus and Alnus. Other Gymnosperms such as Picea and Tsuga were represented by very low percentage. Poaceae and Cyperaceae show their strong presence indicating grassland and wetland conditions around the depositional basin. In the upper zone (DF-II) there is increase of Gymnosperms such as Picea and Abies. The subtropical Gymnosperm Podocarpus decreased while Tsuga completely became absent in this zone. Cold climate preferring trees such as Cedrus, Betula, Juglans and Ulmus appeared first time in this zone. The climate became even colder and drier in the upper part of the section. Near water plants such as Cyperaceae and Typha show their dominance in this zone. -

Neksap Household Food Security and Child Nutrition Monitoring Survey

WFP - World Food Programme NeKSAP Household Food Security and Child Nutrition Monitoring Survey: 2012 Questionnaire Re-design, Survey Re-design, Estimation, and Calibration with 2010 NLSS-III Dr Stephen Haslett Systemetrics Research Ltd www.systemetrics.co.nz May 2012 SUMMARY 1. WFP Nepal has been monitoring food security since 2002. WFP field surveillance capacity consists of a database management system (e-WIN) and integrated electronic data collection via field surveillance staff. The system allows rural, field-based household food security monitoring and analysis in near real-time. The annual sample is approximately 4,000 households, all of which are essentially rural. Data collected includes food security, market situation, water and sanitation, migration patterns, and child nutrition. The household survey is one of the core components of the Nepal Food Security Monitoring System (Nepal Khadhya Surakshya Anugaman Pranali: NeKSAP). The system is currently being institutionalized into the Nepal government system. 2. The data collected has also been used for non-food security purposes such as nutrition (Helen Keller International - HKI, Ministry of Health and Population), education (RIDA, UNICEF, Ministry of Education), and child protection (UNICEF). 3. NeKSAP household survey sampling design has evolved over the years in line with changing information requirements. In 2010, probability sampling was introduced to achieve better representation of seasonality and geographical area, subject to the continuing limitation of the survey to what are essentially rural areas. 4. The 2011 NeKSAP household survey also used probability sampling, although no estimates of accuracy that incorporated the complex survey design (which includes stratification, clustering and unequal selection probabilities) were calculated. -

Nagdhunga-Naubise-Mugling (NNM) Road and Bridges

Public Disclosure Authorized Government of Nepal Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport Department of Roads Development Cooperation Implementation Divisions(DCID) STRATEGIC ROAD CONNECTIVITY AND TRADE IMPROVEMENT PROJECT (SRCTIP) Final Report on Indigenous People Development Plan Public Disclosure Authorized (IPDP) Of Nagdhunga-Naubise-Mugling (NNM) Road and Bridges Environment & Resource Management Consultant (P) Ltd.; Public Disclosure Authorized Group of Engineer’s Consortium (P) Ltd.; and Udaya Consultancy (P.) Ltd. February, 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized i ii iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Project Description Nagdhunga-Naubise-Mugling (NNM) Road is as an important trade and transit routefor linking Kathmandu Valley with Terai region and India. There are other roads as well linking Tarai and Kathmandu valley, but they do not fulfill the required standards for smooth and safe movement of commercial vehicles. NNM road is a part of Asian Highway (AH-42) and is the most important road corridor in Nepal. The road section from Mugling to Kathmandu lies on geologically difficult and fragile hilly and mountainous terrain. Since the average daily traffic in this route is comparatively very high, the present road condition and available facilities are not sufficient to provide the efficient services. Thus, the timely improvement of this road is considered the most important. The project road starts at outskirts of Kathmandu City at a place called Nagdhunga and passes through Sisnekhola, Khanikhola, Naubise, Dharke, Gulchchi, Malekku, Benighat, Kurintar, Manakamana and ends at Mugling Town. The section of project road from Nagdhunga to Naubise (12.3 Km. length) is part of Tribhuvan Highway and the section from Naubise to Mugling (82.4 Km. -

Government of Nepal

Government of Nepal District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development Department of Local Infrastructure Development and Agricultural Roads (DOLIDAR) District Development Committee, KATHMANDU VOLUME-I (MAIN REPORT) AUGUST 2013 Submitted by SITARA Consult Pvt. Ltd. for the District Development Committee (DDC) and District Technical Office (DTO), Kathmandu with Technical Assistance from the Department of Local Infrastructure and Agricultural Roads (DOLIDAR) Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development and grant supported by DFID. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This DTMP Final Report for Kathmandu District has been prepared on the basis of DOLIDAR’s DTMP Guidelines for the Preparation of District Transport Master Plan 2012. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to RTI Sector Maintenance Pilot and DOLIDAR for providing us an opportunity to prepare this DTMP. We would also like to acknowledge the valuable suggestions, guidance and support provided by DDC officials, DTO Engineers and DTICC members and all the participants present in various workshops organized during the preparation this DTMP without which this report would not be in the present form. At last but not the least, we would also like to express our sincere thanks to all the concerned who directly or indirectly helped us in preparing this DTMP. SITARA Consult Pvt. Ltd Kupondole, Lalitpur, Nepal i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Kathmandu District is located in Bagmati Zone of the Central Development Region of Nepal. It borders with Bhaktapur and Kavrepalanchowk district to the East, Dhading and Nuwakot district to the West, Nuwakot and Sindhupalchowk district to the north, Lalitpur and Makwanpur district to the South. The district has one metropolitan city, one municipality and fifty-seven VDCs, ten constituency areas. -

Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in Nepal

Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in Nepal A Civil Society Parallel Report Review Period: April 2007 – July 2013 Submitted to Pre-Sessional Working Group United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Geneva, Switzerland October 2013 Prepared by: ESCR Committee Human Rights Treaty Monitoring Coordination Centre (HRTMCC) Nepal ESCR Committee Coordinator Rural Reconstruction Nepal (RRN) A Civil Society Report on ESCR, 2013, Nepal Overall coordination: Human Rights Treaty Monitoring Coordination Centre (HRTMCC) Secretariat/INSEC Parallel report process coordination: Community Self Reliance Centre (CSRC) Draft contributors: Mr Jagat Basnet, HRTMCC ESCR Committee, CSRC Mr Birendra Adhikari, HRTMCC ESCR Committee, RRN Ms Samjah Shrestha, HRTMCC Secretariat/INSEC Special contributors: Ms Bidhya Chapagain Mr Prakash Gnyawali Committee on ESCR: Coordinator: Rural Reconstruction Nepal (RRN) Members: Lumanti Collective Campaign for Peace (COCAP) Public Health Concern Trust (PHECT) Physician for Social Responsibility, Nepal (PSRN) Community Self Reliance Centre (CSRC) Forest Resources Studies and Action Team (Forest Action) Centre for Protection of Law and Environment (CELP) © ESCR Committee, HRTMCC, 2013, Nepal The Human Rights Treaty Monitoring Coordination Centre (HRTMCC) is a coalition of 63 human rights organizations, functioning as a joint forum for all human rights NGOs in Nepal. It monitors and disseminates information on the status of state obligations to the UN human rights treaties in the form of parallel reports as well as other publications. HRTMCC is also active in domestic lobbying for the protection and promotion of human rights. HRTMCC has previously submitted parallel reports to the UN treaty bodies monitoring CERD, CAT, ICESCR, CEDAW as well as the ICCPR. Materials from this report can be reproduced, republished and circulated with due acknowledgement of the source. -

A Sociolinguistic Study of Dotyali

A Sociolinguistic Study of Dotyali Written by: Stephanie R. Eichentopf Research conducted by: Stephanie R. Eichentopf Sara A. Boon Kimberly D. Benedict Linguistic Survey of Nepal (LinSuN) Central Department of Linguistics Tribhuvan University, Nepal and SIL International 2014 Table of Contents 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 8 1.1 Geography ................................................................................................................ 9 1.2 History of the people ............................................................................................... 9 1.3 Language ................................................................................................................ 11 1.4 Other nearby languages ......................................................................................... 12 1.5 Previous research and resources ............................................................................ 14 2 Purpose and Goals .......................................................................................................... 17 3 Methodology .................................................................................................................. 19 3.1 Instruments ............................................................................................................ 19 3.2 Site selection ......................................................................................................... -

National Population and Housing Census 2011 (National Report)

Volume 01, NPHC 2011 National Population and Housing Census 2011 (National Report) Government of Nepal National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Kathmandu, Nepal November, 2012 Acknowledgement National Population and Housing Census 2011 (NPHC2011) marks hundred years in the history of population census in Nepal. Nepal has been conducting population censuses almost decennially and the census 2011 is the eleventh one. It is a great pleasure for the government of Nepal to successfully conduct the census amid political transition. The census 2011 has been historical event in many ways. It has successfully applied an ambitious questionnaire through which numerous demographic, social and economic information have been collected. Census workforce has been ever more inclusive with more than forty percent female interviewers, caste/ethnicities and backward classes being participated in the census process. Most financial resources and expertise used for the census were national. Nevertheless, important catalytic inputs were provided by UNFPA, UNWOMEN, UNDP, DANIDA, US Census Bureau etc. The census 2011 has once again proved that Nepal has capacity to undertake such a huge statistical operation with quality. The professional competency of the staff of the CBS has been remarkable. On this occasion, I would like to congratulate Central Bureau of Statistics and the CBS team led by Mr.Uttam Narayan Malla, Director General of the Bureau. On behalf of the Secretariat, I would like to thank the Steering Committee of the National Population and Housing census 2011 headed by Honorable Vice-Chair of the National Planning commission. Also, thanks are due to the Members of various technical committees, working groups and consultants.