Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advancing Workers' Rights Under Sdgs

Research Paper IX Advancing Workers’ Rights under SDGs Policy and Situational Analysis of Decent Work in Nepal The Centre for the Study of Labour and Mobility is a research centre within Social Science Baha, Kathmandu, set up with the primary objective of contributing to broader theories and understandings on labour and mobility. It conducts interdisciplinary, policy-relevant research on critical issues affecting working people; serves as a forum to foster academic, policy and public debates; and provides new insights on the impact of labour and migration. Jeevan Baniya with 9 789937934916 Sunita Basnet, Himalaya Kharel and Rajita Dhungana Research Paper IX Advancing Workers’ Rights under SDGs Policy and Situational Analysis of Decent Work in Nepal Jeevan Baniya with Sunita Basnet, Himalaya Kharel and Rajita Dhungana This publication was made possible through the financial support of the Solidarity Center, Washington DC. The authors would like to thank Krishma Sharma of the Solidarity Center for administrative and logistical support during the study. The authors are grateful to Saloman Rajbanshi, Senior Programme Officer and Dr Biswo Poudel, Economic Advisor, from ILO Country Office Nepal, for reviewing the report and providing their valuable feedback. The authors would also like to thank Khem Shreesh at Social Science Baha for his feedback while finalising this publication. © Solidarity Center, 2019 ISBN: 978 9937 9349 1 6 Centre for the Study of Labour and Mobility Social Science Baha 345 Ramchandra Marg, Battisputali, Kathmandu – 9, Nepal Tel: +977-1-4472807, 4480091 • Fax: +977-1-4475215 [email protected] • www.ceslam.org Printed in Nepal CONTENTS Acronyms v Executive Summary vii 1. -

Food Security Bulletin 29

Nepal Food Security Bulletin Issue 29, October 2010 The focus of this edition is on the Mid and Far Western Hill and Mountain region Situation summary Figure 1. Percentage of population food insecure* 26% This Food Security Bulletin covers the period July-September and is focused on the Mid and Far Western Hill and Mountain (MFWHM) 24% region (typically the most food insecure region of the country). 22% July – August is an agricultural lean period in Nepal and typically a season of increased food insecurity. In addition, flooding and 20% landslides caused by monsoon regularly block transportation routes and result in localised crop losses. 18 % During the 2010 monsoon 1,600 families were reportedly 16 % displaced due to flooding, the Karnali Highway and other trade 14 % routes were blocked by landslides and significant crop losses were Oct -Dec Jan-M ar Apr-Jun Jul-Sep Oct -Dec Jan-M ar Apr-Jun Jul-Sep reported in Kanchanpur, Dadeldhura, western Surkhet and south- 08 09 09 09 09 10 10 10 eastern Udayapur. NeKSAP District Food Security Networks in MFWHM districts Rural Nepal Mid-Far-Western Hills&Mountains identified 163 VDCs in 12 districts that are highly food insecure. Forty-four percent of the population in Humla and Bajura are reportedly facing a high level of food insecurity. Other districts with households that are facing a high level of food insecurity are Mugu, Kalikot, Rukum, Surkhet, Achham, Doti, Bajhang, Baitadi, Dadeldhura and Darchula. These households have both very limited food stocks and limited financial resources to purchase food. Most households are coping by reducing consumption, borrowing money or food and selling assets. -

Food Security Bulletin - 21

Food Security Bulletin - 21 United Nations World Food Programme FS Bulletin, November 2008 Food Security Monitoring and Analysis System Issue 21 Highlights Over the period July to September 2008, the number of people highly and severely food insecure increased by about 50% compared to the previous quarter due to severe flooding in the East and Western Terai districts, roads obstruction because of incessant rainfall and landslides, rise in food prices and decreased production of maize and other local crops. The food security situation in the flood affected districts of Eastern and Western Terai remains precarious, requiring close monitoring, while in the majority of other districts the food security situation is likely to improve in November-December due to harvesting of the paddy crop. Decreased maize and paddy production in some districts may indicate a deteriorating food insecurity situation from January onwards. this period. However, there is an could be achieved through the provision Overview expectation of deteriorating food security of return packages consisting of food Mid and Far-Western Nepal from January onwards as in most of the and other essentials as well as A considerable improvement in food Hill and Mountain districts excessive agriculture support to restore people’s security was observed in some Hill rainfall, floods, landslides, strong wind, livelihoods. districts such as Jajarkot, Bajura, and pest diseases have badly affected In the Western Terai, a recent rapid Dailekh, Rukum, Baitadi, and Darchula. maize production and consequently assessment conducted by WFP in These districts were severely or highly reduced food stocks much below what is November, revealed that the food food insecure during April - July 2008 normally expected during this time of the security situation is still critical in because of heavy loss in winter crops, year. -

Summer Paddy Crop Production Increased by 17%

Food Security Bulletin - 19 United Nations World Food Programme FS Bulletin, March 2008 Food Security Monitoring and Analysis System Issue 19 Key Findings 9 Nepal’s summer paddy crop production increased by 17%. 9 Initial reports indicate that the winter crop will yield substantially lower crops in the Mid and Far Western region, due to late winter rains. 9 Market Prices have increased significantly despite these good crop yields leaving an estimated 3.8 million extremely vulnerable. 9 Additionally, many areas in Mid- and Far-West suffered from poor paddy production and are facing increasing food insecurity. The outlook for the winter crop production in many of these areas is also worrying. 9 Many of the extreme poor households in flood affected areas are still struggling to cope with the longer-term affects of the flood. 9 Average household food stocks are down by half compared to a year ago. 9 More households are facing difficulties in accessing sufficient food. Coping strategies are more frequently adopted compared to last quarter and more households find it difficult to find employment. Editorial The past couple of months were the beginning of April. Preliminary Food Security Phase Classification characterized by ongoing bandhs in the expectations are presented on page 4 Map Terai, resulting in shortages of fuel and of this bulletin. other essential items and rising food With support from the SENAC project prices across Nepal. Price rises in In rural areas, the current food security (Strengthening Emergency Needs coarse rice were further exacerbated by situation is largely based upon Assessment Capacity within WFP), the the ongoing ban on export of non- production of the summer crops, maize methodology used to develop the basmati rice from India and the global and rice, as winter wheat has yet to be quarterly food security phase cereal price hikes (see WFP Market harvested. -

Structural Violence Against Children in South Asia © Unicef Rosa 2018

STRUCTURAL VIOLENCE AGAINST CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA © UNICEF ROSA 2018 Cover Photo: Bangladesh, Jamalpur: Children and other community members watching an anti-child marriage drama performed by members of an Adolescent Club. © UNICEF/South Asia 2016/Bronstein The material in this report has been commissioned by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) regional office in South Asia. UNICEF accepts no responsibility for errors. The designations in this work do not imply an opinion on the legal status of any country or territory, or of its authorities, or the delimitation of frontiers. Permission to copy, disseminate or otherwise use information from this publication is granted so long as appropriate acknowledgement is given. The suggested citation is: United Nations Children’s Fund, Structural Violence against Children in South Asia, UNICEF, Kathmandu, 2018. STRUCTURAL VIOLENCE AGAINST CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS UNICEF would like to acknowledge Parveen from the University of Sheffield, Drs. Taveeshi Gupta with Fiona Samuels Ramya Subrahmanian of Know Violence in for their work in developing this report. The Childhood, and Enakshi Ganguly Thukral report was prepared under the guidance of of HAQ (Centre for Child Rights India). Kendra Gregson with Sheeba Harma of the From UNICEF, staff members representing United Nations Children's Fund Regional the fields of child protection, gender Office in South Asia. and research, provided important inputs informed by specific South Asia country This report benefited from the contribution contexts, programming and current violence of a distinguished reference group: research. In particular, from UNICEF we Susan Bissell of the Global Partnership would like to thank: Ann Rosemary Arnott, to End Violence against Children, Ingrid Roshni Basu, Ramiz Behbudov, Sarah Fitzgerald of United Nations Population Coleman, Shreyasi Jha, Aniruddha Kulkarni, Fund Asia and the Pacific region, Shireen Mary Catherine Maternowska and Eri Jejeebhoy of the Population Council, Ali Mathers Suzuki. -

Final Evaluation Combating Exploitive Child Labor Through Education in Nepal: Naya Bato Naya Paila Project -New Path New Steps

FINAL (AFTER COMMENTS) Independent Final Evaluation Combating Exploitive Child Labor through Education in Nepal: Naya Bato Naya Paila Project -New Path New Steps- USDOL Cooperative Agreement No: IL-19513-09-75-K Report prepared by: Dr. Martina Nicolls April 2013 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................ v LIST OF ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................... vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... 1 Country Context ................................................................................................................................................... 1 Relevance: Shifting Project Priorities ................................................................................................................... 1 Effectiveness ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 Efficiency .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Impact .................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Sustainability ....................................................................................................................................................... -

The Kamaiya System of Bonded Labour in Nepal

Nepal Case Study on Bonded Labour Final1 1 THE KAMAIYA SYSTEM OF BONDED LABOUR IN NEPAL INTRODUCTION The origin of the kamaiya system of bonded labour can be traced back to a kind of forced labour system that existed during the rule of the Lichhabi dynasty between 100 and 880 AD (Karki 2001:65). The system was re-enforced later during the reign of King Jayasthiti Malla of Kathmandu (1380–1395 AD), the person who legitimated the caste system in Nepali society (BLLF 1989:17; Bista 1991:38-39), when labourers used to be forcibly engaged in work relating to trade with Tibet and other neighbouring countries. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Gorkhali and Rana rulers introduced and institutionalised new forms of forced labour systems such as Jhara,1 Hulak2, Beth3 and Begar4 (Regmi, 1972 reprint 1999:102, cited in Karki, 2001). The later two forms, which centred on agricultural works, soon evolved into such labour relationships where the workers became tied to the landlords being mortgaged in the same manner as land and other property. These workers overtimes became permanently bonded to the masters. The kamaiya system was first noticed by anthropologists in the 1960s (Robertson and Mishra, 1997), but it came to wider public attention only after the change of polity in 1990 due in major part to the work of a few non-government organisations. The 1990s can be credited as the decade of the freedom movement of kamaiyas. Full-scale involvement of NGOs, national as well as local, with some level of support by some political parties, in launching education classes for kamaiyas and organising them into their groups culminated in a kind of national movement in 2000. -

Council of the European Union

ISSN 1680-9742 QC-AA-05-001-EN-C EN EN COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION GENERAL SECRETARIAT European Union - Union European EU Annual Report This, the seventh EU Annual Report on Human Rights, records the actions and policies undertaken by the EU between 1 July 2004 and 30 on Human Rights June 2005 in pursuit of its goals to promote universal respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. While not an exhaustive account, it Rights-2005 onHuman Annual Report highlights human rights issues that have given cause for concern and what the EU has done to address these, both within the Union and outside it. 2005 EU Annual Report on Human Rights 2005 EU Annual Report on Human Rights, adopted by the Council on 3 October 2005. For further information, please contact the Press, Communication and Protocol Division at the following address: General Secretariat of the Council Rue de la Loi 175 B-1048 Brussels Fax: +32 (0)2 235 49 77 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://ue.eu.int Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this edition. A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server (http://europa.eu.int). Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2005 ISBN 92-824-3179-7 ISSN 1680-9742 © European Communities, 2005 Reproduction is authorised, except for commercial purposes , provided the source is acknowledged. Printed in Belgium 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface................................................................................................................................................................5 1. Introduction..............................................................................................................................................7 2. Developments within the EU ...................................................................................................................8 2.1. -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

Thesis Jiri Pasz.Pdf

UTRECHT UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF GEOSCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF HUMAN GEOGRAPHY AND PLANNING INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT STUDIES MASTER OF SCIENCE THESIS The Starting Point in Life Towards inclusive birth registration in Nepal By Jiří Pasz Thesis supervised by Dr. Paul van Lindert 2011 2 Acknowledgements "Tell me, and I will forget. Show me, and I may remember. Involve me, and I will understand." Confucius The research in Nepal was one of my most valuable work and life experiences. I was amazed by the beauty of Nepal and its people. Besides being amazed, I have learned many valuable lessons, many people have influenced my life and I believe I have influenced theirs too. We have become each other’s guides and even friends during this academic adventure. I am first of all grateful to Paul van Lindert who became the mentor of my research and provided critical, yet friendly advice on all issues I had to deal with during the preparation, research and thesis writing. His input and guidance is very precious indeed and I deeply respect his wisdom and experience. Whenever we travel to another part of the world we wish to have someone there who would make ourselves feel welcome. I found such person in my Nepalese supervisor Indira Thapa. Indira not only introduced me to Plan Nepal but she was always helping me with my tasks, always keen and patient to answer my questions. I am grateful to all the other people in Plan office in Kathmandu for being so kind to me, especially to Donal Keane, Subhakar Baidya and Prem Aryal. -

In the Name of 'Empowerment': Women and Development in Urban Nepal

In the name of ‘empowerment’: women and development in urban Nepal Margaret Becker Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy Department of Anthropology School of Social Sciences, Faculty of Arts The University of Adelaide December 2016 Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................... v Thesis declaration ...................................................................................................... vi Acknowledgements .................................................................................................. vii Transliteration ........................................................................................................... ix List of acronyms and abbreviations ........................................................................... x Introduction ...................................................................................................... 1 Ethnographic locations and methodology .................................................................. 3 Situating the organisations ......................................................................................... 5 Critical perspectives on development ........................................................................ 8 Critical perspectives on empowerment .................................................................... 12 Reflections on empowerment ................................................................................... 18 The structure -

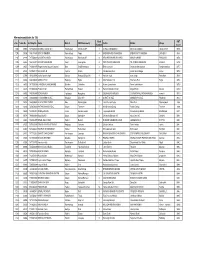

PMT Result 2075 List.Xlsx

Alternate candidates for TSLC Ward PMT S. No. Token No SLC Reg No Name District VDC/Municipality Father Mother Village Number Score 1205 29868 7477022010 BHARAT RAJ BHATT Kanchanpur Bhimdatta NP 8 SHREE NAND BHATT MOTI DEVI BHATT TILACHOUR 997.6 1206 30396 1807718001 BINUTA KHADKA Ramechhap Farpu 4 BADRI BAHADUR KHADKA BISHNU MAYA KHADKA LACHEPU 997.6 1207 32226 7277059022 SUSMITA CHAND Kanchanpur Bhimdatta NP 6 KESHAB BAHADUR CHAND MANJU CHAND BANGAUN 997.6 1208 34943 7441233012 SUSMITA ADHIKARI Kaski Lwangghale 4 TEK PRASAD ADHIKARI TIL KUMARI ADHIKARI KOLELI 997.6 1209 30035 7436031070 Ragani kumari jayswal Jayswal Bara GanjBhawanipur 3 Bhairo parsad Shambha devi jayswal Ganjbhawanipur 997.7 1210 32691 7457005127 SUJATA G M Pyuthan Khaira 2 Nim Bahadur G m Laxmi Gharti Magar Palasi 997.8 1211 32804 7010176010 aasha kumari singh Sunsari RamganjBelgachhi 8 hariram singh nanu singh Ramdhuni 997.8 1212 33666 6946100001 ANDIKA PUN Baglung Righa 6 Man Bahadur Pun Tilachana Pun Righa 997.8 1213 34050 7417059004 CHANDIKA LAMICHHANE Dolakha Chilankha 8 Kumar Lamichhane Rama Lamichhane 997.8 1214 32273 7418082005 Prabin Khatri Ramechhap Deurali 6 Ganesh Bahadur Khatri Maiya Khatri Deurali 997.9 1215 33092 7401013060 SONI MADEN Taplejung Hangdeva 9 SILBAHADUR MADEN SITAMAYA PALUNGWA MADEN eseratol 997.9 1216 33391 7225022009 CHHOISANG GHALE Nuwakot Bidur N.P. 8 SHAKTI GHALE MANMAYA GHALE RAISING 997.9 1217 28738 7436099042 AJAY KUMAR YADAV Bara Madhurijabdi 7 Jhoti Prasad Yadav Mina Devi Madhurijabdi 998 1218 30814 7456070039 PATHA BAHADUR D.C.