In the Name of 'Empowerment': Women and Development in Urban Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CEDAW Shadow Report Writing Process Consultation Meeting on CEDAW Shadow • Take Away on CEDAW Shadow Report Report Writing Process

FWLD’S QUARTERLY ONLINE BulletinVol. 8 Year 3 Jan-Mar, 2019 CEDAW SHADOW REPORT WRITING Working for non-discrimination PROCESS and equality Formation of Shadow Report Preparation Inside Committee (SRPC) • CEDAW Shadow Report Writing Process Consultation Meeting on CEDAW Shadow • Take away on CEDAW Shadow Report Report Writing Process • Take away on Citizenship/Legal Aid Provincial Consultation on draft of CEDAW • Take away on Inclusive Transitional Justice Shadow Report • Take away on Reproductive Health Rights • Take away on Violence against Women Discussion on List of Issues (LOI) • Take away on Status of Implementation of Constitution and International Instruments National Consultation of the CEDAW Shadow • Media Coverage on the different issues initiated by FWLD Report Finalization of CEDAW Shadow Report Participated in the Reveiw of 6th Periodic Report of Nepal on CEDAW Concluding Observations on Sixth Periodic Report of Nepal on CEDAW Take away on CEDAW SHADOW REPORT A productive two days consultative meeting on CEDAW obligations on 2nd and 3rd October 2018. Submission of CEDAW Press meet on CEDAW Shadow Report CEDAW Shadow Report Preparation Committee coordinated by FWLD has submitted the CEDAW Shadow Report and the A press meet was organized on 11th Oct. 2018 to report has been inform media about reporting process of Shadow uploaded in Report on Sixth Periodic Report of Nepal on CEDAW. The timeline of review of the report and its OHCHR’s website on outcome was also discussed. October 1st 2018. NGO Briefs and Informal Country meeting on the Lunch Meeting role of civil society in the 71st Session of CEDAW A country meeting was organized to discuss about the role of civil society in the 71st Session of CEDAW on 11th Oct, 2018. -

Gaaro: Nepali Women Tell Their Stories Sarah Cramer AD: Christina Monson SIT Nepal Fall 2007

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2007 Gaaro: Nepali Women Tell Their tS ories Sarah Cramer SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, and the Politics and Social Change Commons Recommended Citation Cramer, Sarah, "Gaaro: Nepali Women Tell Their tS ories" (2007). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 134. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/134 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gaaro: Nepali Women Tell Their Stories Sarah Cramer AD: Christina Monson SIT Nepal Fall 2007 Dedication: Cramer 2 For every Nepali or bideshi who can learn something from it or already has. For everyone who knows something of human empathy and for those who wish to strive for more. Cramer 3 Acknowledgements: Firstly, I would like to acknowledge Mina Rana for her help with my project. Without her translation help and her endless curiosity which constantly pushed me to reach for more, this paper would have been empty of many things. I also want to thank her for her exuberance and love of learning new things which showed me over and over again the value of such an endeavor as mine. I would secondly like to thank Aarti Bhatt, Rory Katz, and Patrick Robbins for all of our late nights, silly and serious. -

Report: Intersections of Violence Against Women and Girls with Post

Intersections of violence against women and girls with state-building and peace-building: Lessons from Nepal, Sierra Leone and South Sudan Cover image: Josh Estey/CARE The photos in this report do not represent women and girls who themselves have been affected by gender-based violence nor who Table of contents accessed services. Acknowledgements 2 Acronyms 3 Executive summary 4 Background 4 Case study development 5 Overall summary findings 6 Conclusions and recommendations 9 Background 11 Violence against women and girls in conflict and post-conflict settings 11 State-building and peace-building processes 13 The study 15 Intersections of SBPB and VAWG – findings from the literature review 16 A conceptual framework linking state-building and peace-building and violence against women and girls 18 Case studies 22 Overall summary findings 27 Conclusions and recommendations 41 Annexes 47 Annex 1: Methods 48 Annex 2: Analytical framework 50 Annex 3: Nepal case study 56 Annex 4: Sierra Leone case study 68 Annex 5: South Sudan case study 80 Bibliography 94 Funding 100 Partners 101 Intersections of violence against women and girls with state-building and peace-building: Lessons from Nepal, Sierra Leone and South Sudan 1 Acknowledgements Acronyms The overall report and case studies were drafted by Aisling All People’s Congress APC Swaine, Michelle Spearing, Maureen Murphy and Manuel Contreras. Armed Forces Revolutionary Council AFRC In-country support for qualitative research was received Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) CPN (M) from CARE’s country offices in Nepal (particularly Bisika Comprehensive Peace Agreement CPA Thapa), Sierra Leone (particularly Christiana Momoh) and South Sudan (particularly Dorcas Acen). -

Nepali Times, but Only About the Kathmandu District Are You Writing an Article

#217 8-14 October 2004 20 pages Rs 25 Weekly Internet Poll # 157 Q. Should the government announce a unilateral ceasefire before Dasain? Peace by peace Total votes:1,001 ANALYSIS by KUNDA DIXIT Hope is strongest Weekly Internet Poll # 158. To vote go to: www.nepalitimes.com Q. Do you think the human rights situation in s Dasain approaches there are indications that both sides will Nepal has improved or deteriorated in the when things seem most hopeless past one year? observe an unofficial festival truce, but prospects of peace A talks to resolve the conflict are more remote than ever. A purported statement from the Maoists declaring a Dasain-Tihar ceasefire on Tuesday turned out to be a hoax. Rebel spokesman Krishna Bahadur Mahara set the record straight by dashing off an e- statement, but that was followed on Wednesday by another release purportedly signed by Prachanda saying the original statement was correct and action would be taken against Mahara. Analysts do not rule out the possibility of army disinformation at work, and see signs of a rift in the Maoist hierarchy following the groups plenum in Dang last month which reportedly rejected peace talks for now. The meeting was followed by strident anti-Indian rhetoric and an intriguing silence on the part of Baburam Bhattarai, who is said to have favoured a softer line on India. The contradictions between central-level statements about links to fraternal parties and recent attacks on the leftist United Peoples Front in the mid-west hint at a breakdown in control. While the leadership calls on UN mediation, grassroots militia defy international condemnation of forced recruitment of school students, abduction of a Unicef staffer and looting of WFP aid. -

Rebuilding Nepal: Women's Roles in Political Transition and Disaster

Rebuilding Nepal: Women’s Roles in Political Transition and Disaster Recovery BRIANA MAWBY AND ANNA APPLEBAUM Authors Briana Mawby (Hillary Rodham Clinton Research Fellow 2015–17, GIWPS) Anna Applebaum (Hillary Rodham Clinton Research Fellow 2015–17, GIWPS) Expert Advisers Ambassador Melanne Verveer (Executive Director, GIWPS) Roslyn Warren (Former Research Partnerships Manager, GIWPS) Acknowledgements The authors of this report are deeply grateful to the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security and to the many individuals who helped make this report possible. The authors would like to express their profound gratitude to Preeti Thapa (Asia Foundation and mediator/dialogue facilitator) and Margaret Ar- nold (World Bank) for serving as external reviewers of this report. They served in an individual capacity and not on behalf of their respective organizations. The authors would like to thank the following individuals for their advice and support: Ambassador Alaina B. Teplitz, Jasmine-Kim Westendorf, Jeni Klugman, Roslyn Warren, Mayesha Alam, Chloé White, Holly Fuhrman, Sarah Rutherford, Rebecca Turkington, Luis Mancilla, Andrew Walker, Andrea Welsh, Haydn Welch, Katherine Butler-Dines, Alexander Rohlwing, Kayla Elson, Tala Anchassi, Elizabeth Dana, Abigail Nichols, and Meredith Forsyth. The authors would also like to express deep gratitude to Reeti K. C. and Claire Naylor for their contributions and support. The Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security Georgetown University’s Institute for Women, Peace and Security (GIWPS) seeks to promote a more stable, peaceful, and just world by focusing on the important role women play in preventing conflict and building peace, growing economies, and addressing global threats like climate change and violent extremism. -

Nepal COBP 2011-2013

Summary Report - Consultations with Stakeholders - 2009-2010 I. Introduction The Asian Development Bank (ADB), UK Department for International Development (DFID), and the World Bank (WB) held joint country consultations held in October- November 2008 with the aim to get insights from a wide range of stakeholders on what role they should play in supporting Nepal's development efforts. After the joint consultations, all the three agencies have developed their Country Business/Assistance Plans for their programs in Nepal. The three agencies decided to go back to the stakeholders and share these plans with them and seek their suggestions on how the proposed strategies could be effectively implemented. In this context, ADB contracted HURDEC (P). Ltd. to design and implement the consultation events. This report summarizes the findings and outcomes of the discussions and is organized as follows. The first part of the report summarizes the overall findings, and next part presents a summary of the recommendations from each event. The list of participants is annexed to this report. II. Locations and Process All the consultation events took place from December 2009 till April 2010. Consultations were held with the following stakeholders and locations: • Private Sector • Youth • Civil Society • Women and Excluded Groups • Nepalgunj • Pokhara • Biratnagar • GON Secretaries. In the locations outside Kathmandu, two events were held - one with community groups (CBOs, users' groups, women groups etc.); and second with district level political leaders, district line agencies, INGO/NGO representatives, project/program staff, youth and journalists. In each location, participants came from an average of 15 districts. Refer below for a map of Nepal showing districts from where participants attended the events. -

Priority Areas for Addressing Sexual and Gender Based Violence in Nepal

Report UNFPA Nepal Priority Areas for Addressing Sexual and Gender Based Violence in Nepal HURDEC, May 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Context ............................................................................................ 1 II. Framework and Methodology ......................................................... 2 III. Women, Peace and Security related Initiatives ............................. 2 IV. Sexual and Gender Based Violence (SGBV), Conflict and Peace 5 V. Key Initiatives regarding SGBV ...................................................... 7 5.1 Service Providers: ..................................................................... 8 5.2. Area Coverage, Target Groups and Implementing Partners .... 9 5.3. Institutional Measures taken regarding SGBV ........................ 10 VI. Assessment of Areas of Improvement in existing SGBV related interventions: .................................................................................... 12 VII. Recommendations - Priority Areas for UNFPA .......................... 14 7.1. Increase capacity of service providers at all levels ................. 15 7.2 Strengthen/Build Partnerships ................................................. 15 7.3 Support establishment of community level women's groups networks for prevention and protection. ........................................ 16 ANNEXES ........................................................................................ 17 Report - Identifying UNFPA Nepal priority areas for SGBV I. Context Impact of the 11 year insurgency in -

Silence Breaking the Silence

www.fridayweekly.com.np Every Thursday | ISSUE 194 | RS. 20 SUBSCRIBER COPY | ISSN 2091-1092 13 NOVEMBER 2013 @& sflt{s @)&) 9 772091 109009 www.facebook.com/fridayweekly Silence Breaking the Silence 9/11 will experience the country’s loudest musical explosion this year in the form of Silence Festival, allowing fans an opportunity to witness great acts right here in the city. Continued on page 2 Model: Ashma Singh Model: 2007 record “The Apostasy” At a glance was inspired by his trip here. getstarted What Silence Festival start off with our picks Hailed for the last two decades as one of the few metal bands Who Silence Entertainment getting better with each album, When Behemoth could be the ultimate 9 November (Saturday) Silence Breaking the Silence treat for fans here. Time 12:00 pm onwards Samyam Shrestha Opening for the Polish Where Bhrikuti Mandap Fun Park juggernauts are six killer eavy metal has come here has steadily grown. It was bands from Nepal, India and Ticket Price Rs. 700 a long way in Nepal as if the Michael Jacksons of Switzerland - UgraKarma, Hsince its introduction in metal were playing here one Underside, Newaz, Jugaa, to promote our music and bring While the previous editions late 80s-early 90s. But until after the other, while the people Zygnema, Derrick and And it to an international standard. I of the festival were held at a few years ago, no major beyond the metal circle were We Came. The festival has believe it’s getting better every Jawlakhel Football Ground, international metal band had totally oblivious to it all. -

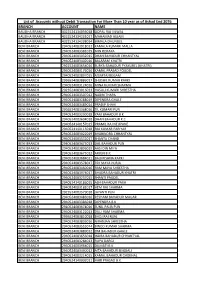

Branch Account Name

List of Accounts without Debit Transaction For More Than 10 year as of Ashad End 2076 BRANCH ACCOUNT NAME BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134056018 GOPAL RAJ SILWAL BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134231017 MAHAMAD ASLAM BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134298014 BIMALA DHUNGEL BENI BRANCH 2940524083918012 KAMALA KUMARI MALLA BENI BRANCH 2940524083381019 MIN ROKAYA BENI BRANCH 2940524083932015 DHAN BAHADUR CHHANTYAL BENI BRANCH 2940524083402016 BALARAM KHATRI BENI BRANCH 2922524083654016 SURYA BAHADUR PYAKUREL (KHATRI) BENI BRANCH 2940524083176016 KAMAL PRASAD POUDEL BENI BRANCH 2940524083897015 MUMTAJ BEGAM BENI BRANCH 2936524083886017 SHUSHIL KUMAR KARKI BENI BRANCH 2940524083124016 MINA KUMARI SHARMA BENI BRANCH 2923524083016013 HASULI KUMARI SHRESTHA BENI BRANCH 2940524083507012 NABIN THAPA BENI BRANCH 2940524083288019 DIPENDRA GHALE BENI BRANCH 2940524083489014 PRADIP SHAHI BENI BRANCH 2936524083368016 TIL KUMARI PUN BENI BRANCH 2940524083230018 YAM BAHADUR B.K. BENI BRANCH 2940524083604018 DHAN BAHADUR K.C BENI BRANCH 2940524140157015 PRAMIL RAJ NEUPANE BENI BRANCH 2940524140115018 RAJ KUMAR PARIYAR BENI BRANCH 2940524083022019 BHABINDRA CHHANTYAL BENI BRANCH 2940524083532017 SHANTA CHAND BENI BRANCH 2940524083475013 DAL BAHADUR PUN BENI BRANCH 2940524083896019 AASI DIN MIYA BENI BRANCH 2940524083675012 ARJUN B.K. BENI BRANCH 2940524083684011 BALKRISHNA KARKI BENI BRANCH 2940524083578017 TEK MAYA PURJA BENI BRANCH 2940524083460016 RAM MAYA SHRESTHA BENI BRANCH 2940524083974017 BHADRA BAHADUR KHATRI BENI BRANCH 2940524083237015 SHANTI PAUDEL BENI BRANCH 2940524140186015 -

Cover Final.Indd

The Landmark Decisions of THE SUPREME COURT, NEPAL on GENDER JUSTICE NJA-Nepal Publisher: National Judicial Academy Hariharbhawan, Lalitpur Nepal The Landmark Decisions of the Supreme Court, Nepal on Gender Justice Editor Dr. Ananda Mohan Bhattarai NJA - Nepal National Judicial Academy Hariharbhawan, Lalitpur Nepal Advisor: Hon. Tope Bahadur Singh, Executive Director, NJA Translators: Hon. Dr. Haribansh Tripathi, Judge – CoA Mr. Shree Prasad Pandit, Advocate Mr. Sajjan Bar Singh Thapa, Advocate Management & Editorial Assistance Hon. Narishwar Bhandari, Faculty/Judge – DC, NJA Mr. Nripadhwoj Niroula, Registrar Mr. Shree Krishna Mulmi, Research Officer Mr. Paras Paudel, Statistical Officer Mr. Rajan Kumar KC, Finance Coordinator Assistants: Mr. Bishnu Bahadur Baruwal, Publication Assistant Ms. Poonam Lakhey, Office Secretary Ms. Sami Moktan, Administration Assistant Ms. Patrika Basnet, Personal Secretary Copy Rights: © National Judicial Academy/ UNIFEM, Nepal, 2010 Publishers: National Judicial Academy, Nepal Harihar Bhawan, Lalitpur & United Nations Fund for Women (UNIFEM) 401/42 Ramshah Path, Thapathali, Kathmandu Nepal Printing Copies: 500 Copies Financial Assistance: United Nations Fund for Women (UNIFEM) 401/42 Ramshah Path, Thapathali, Kathmandu Nepal Tel No: 977-1-425510/4254899 Fax No: 977-1-4247265 URL: www.unifem.org Printing: Format Printing Press, Hadigoan, Kathmandu Editor’s Note The decisions in this volume basically represent the second generation cases relating to gender justice in Nepal. I call them second generation because in the first generation (1990- 2005) the struggle was for securing women’s right to parental property, their rights against discrimination, their reproductive rights etc culminating in the parliamentary enactment 2005/6 which repealed many provisions of the National Code and other laws, found to be discriminatory on the basis of sex. -

Epicentre to Aftermath Edited by Michael Hutt, Mark Liechty, Stefanie Lotter Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-83405-6 — Epicentre to Aftermath Edited by Michael Hutt, Mark Liechty, Stefanie Lotter Frontmatter More Information Epicentre to Aftermath Epicentre to Aftermath makes both empirical and conceptual contributions to the growing body of disaster studies literature by providing an analysis of a disaster aftermath that is steeped in the political and cultural complexities of its social and historical context. Drawing together scholars from a range of disciplines, this book highlights the political, historical, cultural, artistic, emotional, temporal, embodied and material dynamics at play in the earthquake aftermath. Crucially, it shows that the experience and meaning of a disaster are not given or inevitable, but are the outcome of situated human agency. The book suggests a whole new epistemology of disaster consequences and their meanings, and dramatically expands the field of knowledge relevant to understanding disasters and their outcomes. Michael Hutt is a scholar of Nepali literature and Emeritus Professor of Nepali and Himalayan Studies at SOAS, University of London. He has authored and edited fourteen books and over fifty articles and book chapters on Nepali and Himalayan topics. He co-edited, with Pratyoush Onta, Political Change and Public Culture in Post-1990 Nepal, which was published by the Press in 2017. Mark Liechty is Professor of Anthropology and History at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He is a cultural anthropologist by training and has been a student of Nepali and South Asian culture and history for more than three decades. He is the author of influential books on modern Nepal and a oundingf co-editor of the journal Studies in Nepali History and Society. -

Adolescent Girls' Capabilities in Nepal

GAGE Report: Title Adolescent girls’ capabilities in Nepal The state of the evidence Alex Cunningham and Madeleine D’Arcy d December 2017 Disclaimer Gender and Adolescence: Global Evidence (GAGE) is a nine-year longitudinal research programme building knowledge on good practice programmes and policies that support adolescent girls in the Global South to reach their full potential. Acknowledgements This document is an output of the programme which is The authors of this report are Alex Cunningham and funded by UK Aid from the UK Department for International Madeleine D’Arcy. The authors would like to thank Rachel Development (DFID). The views expressed and information Marcus and Nicola Jones for comments on previous contained within are not necessarily those of or endorsed versions, Denise Powers for copy-editing and Alexandra by DFID, which accepts no responsibility for such views or Vaughan, Gabbi Gray and Jojoh Faal for formatting. information or for any reliance placed on them. Table of Contents Acronyms and abbreviations ............................................................................................................... i Executive summary ...........................................................................................................................ii Report objectives ............................................................................................................................... ii Methodology ....................................................................................................................................