The DNA Fingerprinting Story Mark a Jobling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): the Second Generation of DNA Analysis Methods Takes the Stand, 9 Santa Clara High Tech

Santa Clara High Technology Law Journal Volume 9 | Issue 1 Article 8 January 1993 The olP ymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): The Second Generation of DNA Analysis Methods Takes the Stand Kamrin T. MacKnight Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/chtlj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Kamrin T. MacKnight, The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): The Second Generation of DNA Analysis Methods Takes the Stand, 9 Santa Clara High Tech. L.J. 287 (1993). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/chtlj/vol9/iss1/8 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Clara High Technology Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POLYMERASE CHAIN REACTION (PCR): THE SECOND GENERATION OF DNA ANALYSIS METHODS TAKES THE STAND Kamrin T. MacKnightt TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................... 288 BASIC GENETICS AND DNA REPLICATION ................. 289 FORENSIC DNA ANALYSIS ................................ 292 Direct Sequencing ....................................... 293 Restriction FragmentLength Polymorphism (RFLP) ...... 294 Introduction .......................................... 294 Technology ........................................... 296 Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) ....................... 300 H istory ............................................... 300 Technology .......................................... -

Mittelalterliche Migrationen Als Gegenstand Der "Genetic History"

Jörg Feuchter Mittelalterliche Migrationen als Gegenstand der ‚Genetic History‘ Zusammenfassung Genetic History untersucht historische Fragen mit der Quelle DNA. Migrationen sind ihr Hauptgegenstand, woraus sich eine große Bedeutung für die Mediävistik ergibt. Doch bis vor kurzem waren Historiker nicht beteiligt. Der Beitrag gibt eine Definition der neuen Dis- ziplin (), untersucht die Rolle des Konzeptes Migration in der Populationsgenetik () und beschreibt den Stand der Migrationsforschung in der Mediävistik (). Anschließend gibt er einen kurzen Überblick über die von der Genetic History untersuchten Migrationsräu- me (), betrachtet exemplarisch zunächst eine Studie zur angelsächsischen Migration nach Britannien () und dann ein aktuelles Projekt, in dem erstmals ein Mediävist die Leitung innehat (). Der Beitrag endet mit einigen allgemeinen Beobachtungen und Postulaten (). Keywords: Genetik; DNA; Mittelalter; Angelsachsen; Langobarden; Völkerwanderung. Genetic History is the study of historical questions with DNA as a source. Migrations are its main subject. It is thus very relevant to Medieval Studies. Yet until recently historians have not been involved. The contribution provides a definition of the new discipline (), explores the role of migration as a concept in Population Genetics () and describes the state of migration studies in Medieval History (). It then sets out for an overview of medieval migratory areas studied by Genetic History () and takes an exemplary look first () at a study on Anglo-Saxon migration to Britain and later () at a current project where for the first time a medieval historian has taken the lead. The contribution ends () with some general observations and stipulations. Keywords: Genetics; DNA; Middle Ages; Anglo-Saxons; Lombards; Migration Period. Danksagung: Der Verfasser dankt Prof. Dr. Veronika Lipphardt (University College Frei- burg) und der von ihr von bis geleiteten Nachwuchsgruppe Twentieth Century Felix Wiedemann, Kerstin P. -

Final Programme

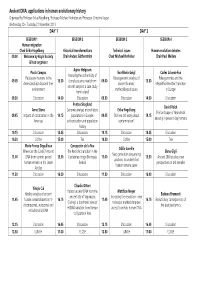

Ancient DNA: applications in human evolutionary history Organised by Professor Erika Hagelberg, Professor Michael Hofreiter and Professor Christine Keyser Wednesday 20 - Thursday 21 November 2013 DAY 1 DAY 2 SESSION 1 SESSION 2 SESSION 3 SESSION 4 Human migration Chair Erika Hagelberg Historical transformations Technical issues Human evolution debates 09.00 Welcome by Royal Society Chair Anders Götherström Chair Michael Hofreiter Chair Paul Mellars & lead organiser Agnar Helgason Paula Campos Eva-Maria Geigl Carles Lalueza-Fox Assessing the authenticity of Pleistocene humans in the Palaeogenomic analysis of Paleogenomics and the 09.05 13.30 clonal sequence reads from 09.00 13.30 Americans/East Asia and their ancient humans: Mesolithic-Neolithic transition ancient samples: a case study environment methodological issues in Europe from Iceland 09.30 Discussion 14.00 Discussion 09.30 Discussion 14.00 Discussion Pontus Skoglund David Reich Anne Stone Genomic analysis of prehistoric Erika Hagelberg The landscape of Neandertal 09.45 Impacts of colonization in the 14.15 populations in Europe: 09.45 Shall we still worry about 14.15 ancestry in present-day humans Americas authentication and population contamination? history 10.15 Discussion 14.45 Discussion 10.15 Discussion 14.45 Discussion 10.30 Coffee 15.00 Tea 10.30 Coffee 15.00 Tea Marie-France Deguilloux Concepción de la Rua Odille Loreille Where are the Caribs? Ancient The Neolithic transition in the Elena Gigli Next generation sequencing 11.00 DNA from ceramic period 15.30 Cantabrian fringe -

Profile of Alec J. Jeffreys

Profile of Alec J. Jeffreys s one of the great contributors to modern genetics, Sir Alec Jeffreys was born with curiosity in his genes as the son and Agrandson of prolific inventors. Jeffreys displayed an insatiable quest for knowl- edge, and his father fostered his son’s budding scientific interests with gifts of a microscope and chemistry set, the latter of which produced one of Jeffreys’ most memorable scientific ventures. ‘‘Those were back in the happy days of chemis- try,’’ Jeffreys points out, ‘‘where you could go down to your local pharmacist and get virtually everything you wanted.’’ The end result of that chemistry experiment was the detonation of his aunt’s apple tree and a set of scars that Jeffreys still bears to- day. ‘‘You learn science very fast that way,’’ he says, ‘‘but it was quite fun.’’ Jeffreys’ scientific curiosity only in- creased after the apple tree incident, and years later it would lead to one of the Alec J. Jeffreys most widely used applications in genetics: DNA fingerprinting. Among other uses, the DNA fingerprinting technique has freys go there, so Jeffreys entered the turn led to another groundbreaking find- helped solve numerous criminal investi- university in 1968. He was at first intent ing about the composition of eukaryotic gations, settle countless paternity dis- on pursuing a degree in biochemistry DNA: introns (3). ‘‘I was 27 at the time, putes, and spark a resurgence of interest but soon decided to alter his course. so still a real rookie, with the ability to in the forensic sciences. That achieve- ‘‘This was no criticism of the way it was detect single-copy DNA by Southern blot ment alone is worthy of merit, contrib- taught,’’ he says of biochemistry at Ox- hybridization and a nice paper on introns uting to Jeffreys’ receiving three high ford, ‘‘but rather a reflection of the fac- under my belt, which is, yeah, not a bad distinctions in 2005: the Albert Lasker ulty’s research, which leaned heavily to start,’’ he says. -

Past Human Migrations in East Asia: Matching Archaeology, Linguistics

16 A genetic perspective on the origins and dispersal of the Austronesians Mitochondrial DNA variation from Madagascar to Easter Island Erika Hagelberg, Murray Cox, Wulf Schiefenhövel, and Ian Frame Introduction This chapter describes the study of one genetic system, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), within the Austronesian-speaking world, and discusses whether the patterns of genetic variation at this genetic locus are consistent with the principal models of the settlement and linguistic diversity in this vast geographical region. Mitochondria are the seat of cellular metabolism and have their own complement of DNA. MtDNA is a tiny proportion of the genetic makeup of a human being, and has both advantages and disadvantages in population studies. It is inherited maternally, in contrast with the nuclear chromosomal DNA inherited from both parents. (Note: the mitochondria of the spermatozoon are eliminated from the egg soon after fertilization, so offspring do not inherit paternal mtDNA, although there are exceptions to this rule, as shown by Schwartz and Vissing 2002.) The maternal mode of inheritance permits the study of female lineages through time. Despite the small size of the mitochondrial genome, each mitochondrion has many thousands of copies of mtDNA, and there are many mitochondria in each cell. The abundance of mtDNA in cells has been exploited in anthropological research on ancient, rare or degraded biological samples, including archaeological bones, old hair samples, or dried blood (Hagelberg 1994). MtDNA accumulates mutations at a relatively fast rate, and so is useful for the investigation of recent evolutionary events. These features have made mtDNA an excellent marker for geneticists interested in human evolutionary history (see Wallace 1995 for review). -

A Lecture by Professor Erika Hagelberg

H-Announce Is there such a thing as a Jewish genome? A lecture by Professor Erika Hagelberg Announcement published by Leah Sidebotham on Friday, April 1, 2016 Type: Lecture Date: April 12, 2016 Location: United Kingdom Subject Fields: Research and Methodology, Jewish History / Studies, Holocaust, Genocide, and Memory Studies, History of Science, Medicine, and Technology, Contemporary History New developments in DNA technology are having a huge impact on industry, medical science and forensic identification. They have also opened new opportunities for research in archaeology and human evolution, as we have seen in the recent identification of the skeleton of Richard III, and the advances in Neanderthal genetics. The technology is also aiding a growing industry in genetic genealogies, where human identity is defined in terms of patterns of DNA variants, obtained easily and cheaply from commercial companies, and giving rise to controversial notions, like that of a Jewish genome. In this talk Professor Hagelberg will describe the opportunities offered by human evolutionary genetics, as well as some of the limitations and more troubling aspects of research on genetic genealogies. Erika Hagelberg’s father came to the UK on a Kindertransport in 1939, aged 13. She studied biochemistry in London and gained a PhD at Cambridge. Her main field of research is the analysis of DNA from archaeological bones, and she has worked on several high-profile cases, including the identification of the skeletal remains of Joseph Mengele and of the Romanov family. She is professor of evolutionary biology at the University of Oslo, and Cheney Fellow in the Arts at the University of Leeds. -

DNA and the Dead Sea Scrolls

Putting the Pieces Together: DNA and the Dead Sea Scrolls Scott R. Woodward A number of questions concerning the origin and production of the Dead Sea Scrolls may be addressed using DNA analysis. These documents were for the most part written on what is thought to be goat- or sheepskin parchment. Based on radiocarbon and other analyses, these manuscripts date between the mid–second century BCE and the rst century CE.1 Under most conditions it would be remarkable that organic material, like parchment, would survive intact after such a long period of time. However, some of the material is remarkably well preserved because of the unique climate and storage conditions at Qumran. Because these parchments were produced from animal skins, they may contain remnant DNA molecules. Within the last decade, new techniques in molecular biology have been developed that have made it possible to recover DNA from ancient sources. The molecular analysis of ancient DNA (aDNA) from the Judean desert parchment fragments would enable us to establish a genetic signature unique for each manuscript. The precision of the DNA analysis will allow us to identify the species, population, and individual animal from which the parchment was produced. Background The ability to recover biomolecules, most importantly DNA, from ancient remains has opened new research that has many implications.2 Access to aDNA provides the opportunity to study the genetic material of past organisms and identify individual and population histories. Unfortunately, the DNA recovered from archaeological specimens is of such a degraded nature that the usual techniques associated with DNA ngerprinting cannot be used. -

Nature Medicine Essay

COMMENTARY LASKER CLINICAL MEDICAL RESEARCH AWARD Genetic fingerprinting Alec J Jeffreys Southern, n.2 Used attrib. (chiefly in by good fortune, teamed up with Richard Southern blot, blotting: see *BLOT n.1 1 f, Flavell on a project to purify a single-copy *BLOTTING vbl. n. 4) with reference to a mammalian gene—the gene encoding rab- technique for the identification of specific bit β-globin—by mRNA hybridization. The nucleotide sequences in DNA, in which problem was how to monitor purification. The fragments separated on a gel are trans- answer was provided by Ed Southern and his ferred directly to a second medium on blots (incidentally, and with typical modesty, http://www.nature.com/naturemedicine which assay by hybridization, etc., may be Ed never calls them Southerns but generally carried out. DNA transfers), which we showed, much to Genetic fingerprinting, the obtaining or our surprise, were capable of detecting single- comparing of genetic fingerprints for iden- copy genes in complex genomes. This led to the tification; spec. the comparison of DNA in a first physical map of a mammalian gene1 and person’s blood with that identified in matter one of the first descriptions of introns2. found at the scene of a crime, etc. – Oxford English Dictionary Human DNA variation Figure 1 Alec Jeffreys at age eight. A budding In 1977 I moved to the Department of Genetics scientist not yet familiar with the focal plane. There can be few higher accolades in sci- at the University of Leicester and, at the tender ence than making it into the Oxford English age of 27, was faced with the thorny issue of Dictionary—except perhaps receiving the where to go next with this arcane new science tively uninformative biallelic markers. -

Genetic Affinities of Prehistoric Easter Islanders: Reply to Langdon Erika Hagelberg University of Cambridge

Rapa Nui Journal: Journal of the Easter Island Foundation Volume 9 Article 4 Issue 1 Rapa Nui Journal 9#1, March 1995 1995 Genetic Affinities of Prehistoric Easter Islanders: Reply to Langdon Erika Hagelberg University of Cambridge Follow this and additional works at: https://kahualike.manoa.hawaii.edu/rnj Part of the History of the Pacific slI ands Commons, and the Pacific slI ands Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Hagelberg, Erika (1995) "Genetic Affinities of Prehistoric Easter Islanders: Reply to Langdon," Rapa Nui Journal: Journal of the Easter Island Foundation: Vol. 9 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://kahualike.manoa.hawaii.edu/rnj/vol9/iss1/4 This Commentary or Dialogue is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Hawai`i Press at Kahualike. It has been accepted for inclusion in Rapa Nui Journal: Journal of the Easter Island Foundation by an authorized editor of Kahualike. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hagelberg: Genetic Affinities of Prehistoric Easter Islanders Genetic Affinities of Prehistoric Easter Islanders: Reply to Langdon Erika Hagelberg, Ph.D. Department ofBiological Anthropology, University ofCambridge, CB2 3DZ, United Kingdom Last year my colleagues and I published a short article in used to follow female lineages in the same way that surnames the journal Nature (Hagelberg et al. 1994) describing the can be used to trace male lineages. analysis of genetic polymorphisms in bones of prehistoric MtDNA is fairly variable in human populations. For Easter Islanders. A few months later I was interested to read instance, in a survey of 100 Caucasian males in Britain, a manuscript disputing our DNA result, submitted by Robert Piercy et al. -

Ancient Dna: a Multifunctional Tool for Resolving Anthropological Questions

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Departament de Biologia Animal, de Biologia Vegetal i d’Ecologia Unitat d’Antropologia Biològica ANCIENT DNA: A MULTIFUNCTIONAL TOOL FOR RESOLVING ANTHROPOLOGICAL QUESTIONS Marc Simón Martínez PhD dissertation 2015 This research received support from Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia in the project entitled “Efectos de la insularidad, migración y cultura en la evolución de la población humana de Menorca durante la edad de bronce” (CGL2008-00800, CGL2005-02567) and from Institut Menorquí d’Estudis in the project entitled “Caracterización genética de la población de Son Olivaret” (IME2006-01). ANCIENT DNA: A MULTIFUNCTIONAL TOOL FOR RESOLVING ANTHROPOLOGICAL QUESTIONS Dissertation presented by Marc Simón Martínez in fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate in Biodiversity of Department de Biologia Animal, de Biologia Vegetal i d’Ecologia, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, directed by: Dr. Assumpció Malgosa, Chair Professor at Unitat d’Antropologia Biològica, Departament de Biologia Animal, de Biologia Vegetal i d’Ecologia, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Dr. Assumpció Malgosa Marc Simón Martínez Sigue mi voz. Sigue mi voz. Ábrete camino hasta mí. Combate la oscuridad. La desesperación. Lucha hasta que luchar sea imposible. Y luego vuelve a abrirte camino hasta mí. Sigue mi voz. Sigue mi voz. Joseph Michael Straczynski, writer ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is very difficult to try to sum up in a few lines the greetings to all the people with whom I shared this journey, so I will start right now. I apologize first as I will only mention the people with whom I’ve coincided the most. Otherwise the list would be endless, but I want to thank all of them. -

The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): the Second Generation of DNA Analysis Methods Takes the Stand, 20 Santa Clara High Tech

Santa Clara High Technology Law Journal Volume 20 | Issue 1 Article 4 January 2004 The olP ymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): The Second Generation of DNA Analysis Methods Takes the Stand Kamrin T. MacKnight Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/chtlj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Kamrin T. MacKnight, The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): The Second Generation of DNA Analysis Methods Takes the Stand, 20 Santa Clara High Tech. L.J. 95 (2003). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/chtlj/vol20/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Clara High Technology Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POLYMERASE CHAIN REACTION (PCR): THE SECOND GENERATION OF DNA ANALYSIS METHODS TAKES THE STAND Kamrin T. MacKnightt TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................... 288 BASIC GENETICS AND DNA REPLICATION ................. 289 FORENSIC DNA ANALYSIS ................................ 292 Direct Sequencing ....................................... 293 Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP) ...... 294 Introduction .......................................... 294 Technology ........................................... 296 Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) ....................... 300 H istory ............................................... 300 Technology .......................................... -

Technical Tips for Obtaining Reliable DNA Identification of Historic Human Remains

Technical Tips for Obtaining Reliable DNA Identification of Historic Human Remains Dongya Y. Yang and Camilla F. Speller ABSTRACT As a Forensic Identification DNA analysis has become an important tool for the The use of DNA for identification of historic human re- identification of historic individuals. False results may mains is similar to forensic DNA individual identification, occur if the historic sample becomes contaminated. as both are dependent upon a match or mismatch for iden- Both historic archaeologists and DNA researchers are tification (Wilson et al. 1995). Nonetheless, there are some provided here with specific technical tips in order to major differences between the two types of cases. Unlike obtain reliable DNA results: (1) historic bone samples modern forensic DNA analysis that can use multiple nu- should be clean collected for DNA analysis; (2) short, clear DNA markers for identification, historic DNA cases overlapping mitochondrial DNA fragments should are usually restricted to analyzing mitochondrial DNA, be used for the historic bone samples, while longer which is more likely to survive degradation over time due mtDNA fragments should be targeted for the assumed to its high copy number per cell (O’Rourke et al. 2000; living relatives; and (3) hair or cheek swab samples from Kaestle and Horsburgh 2002). Since mtDNA serves as a the assumed relatives should be collected and analyzed single DNA marker, it has limited discrimination power. only after the bone DNA analysis is completed. Due to its maternal inheritance pattern, however, it can be a benefit for identification of historic human remains Introduction through the comparison of mitochondrial sequences with those of living relatives (Gill et al.