The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): the Second Generation of DNA Analysis Methods Takes the Stand, 20 Santa Clara High Tech

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRESS RELEASE National Academies and the Law Collaborate

The Royal Society of Edinburgh, Scotland's National Academy, is Scottish Charity No. SC000470 PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release: 11 April 2016 National academies and the law collaborate to provide better understanding of science to the courts The Lord Chief Justice, The Royal Society and Royal Society of Edinburgh today (11 April 2016) announce the launch of a project to develop a series of guides or ‘primers’ on scientific topics which is designed to assist the judiciary, legal teams and juries when handling scientific evidence in the courtroom. The first primer document to be developed will cover DNA analysis. The purpose of the primer documents is to present, in plain English, an easily understood and accurate position on the scientific topic in question. The primers will also cover the limitations of the science, challenges associated with its application and an explanation of how the scientific area is used within the judicial system. An editorial board, drawn from the judicial and scientific communities, will develop each individual primer. Before publication, the primers will be peer reviewed by practitioners, including forensic scientists and the judiciary, as well as the public. Lord Thomas, Lord Chief Justice for England and Wales says, “The launch of this project is the realisation of an idea the judiciary has been seeking to achieve. The involvement of the Royal Society and Royal Society of Edinburgh will ensure scientific rigour and I look forward to watching primers develop under the stewardship of leading experts in the fields of law and science.” Dr Julie Maxton, Executive Director of the Royal Society, says, “This project had its beginnings in our 2011 Brain Waves report on Neuroscience and the Law, which highlighted the lack of a forum in the UK for scientists, lawyers and judges to explore areas of mutual interest. -

Medical Advisory Board September 1, 2006–August 31, 2007

hoWard hughes medical iNstitute 2007 annual report What’s Next h o W ard hughes medical i 4000 oNes Bridge road chevy chase, marylaNd 20815-6789 www.hhmi.org N stitute 2007 a nn ual report What’s Next Letter from the president 2 The primary purpose and objective of the conversation: wiLLiam r. Lummis 6 Howard Hughes Medical Institute shall be the promotion of human knowledge within the CREDITS thiNkiNg field of the basic sciences (principally the field of like medical research and education) and the a scieNtist 8 effective application thereof for the benefit of mankind. Page 1 Page 25 Page 43 Page 50 seeiNg Illustration by Riccardo Vecchio Südhof: Paul Fetters; Fuchs: Janelia Farm lab: © Photography Neurotoxin (Brunger & Chapman): Page 3 Matthew Septimus; SCNT images: by Brad Feinknopf; First level of Rongsheng Jin and Axel Brunger; iN Bruce Weller Blake Porch and Chris Vargas/HHMI lab building: © Photography by Shadlen: Paul Fetters; Mouse Page 6 Page 26 Brad Feinknopf (Tsai): Li-Huei Tsai; Zoghbi: Agapito NeW Illustration by Riccardo Vecchio Arabidopsis: Laboratory of Joanne Page 44 Sanchez/Baylor College 14 Page 8 Chory; Chory: Courtesy of Salk Janelia Farm guest housing: © Jeff Page 51 Ways Illustration by Riccardo Vecchio Institute Goldberg/Esto; Dudman: Matthew Szostak: Mark Wilson; Evans: Fred Page 10 Page 27 Septimus; Lee: Oliver Wien; Greaves/PR Newswire, © HHMI; Mello: Erika Larsen; Hannon: Zack Rosenthal: Paul Fetters; Students: Leonardo: Paul Fetters; Riddiford: Steitz: Harold Shapiro; Lefkowitz: capacity Seckler/AP, © HHMI; Lowe: Zack Paul Fetters; Map: Reprinted by Paul Fetters; Truman: Paul Fetters Stewart Waller/PR Newswire, Seckler/AP, © HHMI permission from Macmillan Page 46 © HHMI for Page 12 Publishers, Ltd.: Nature vol. -

The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): the Second Generation of DNA Analysis Methods Takes the Stand, 9 Santa Clara High Tech

Santa Clara High Technology Law Journal Volume 9 | Issue 1 Article 8 January 1993 The olP ymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): The Second Generation of DNA Analysis Methods Takes the Stand Kamrin T. MacKnight Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/chtlj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Kamrin T. MacKnight, The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): The Second Generation of DNA Analysis Methods Takes the Stand, 9 Santa Clara High Tech. L.J. 287 (1993). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/chtlj/vol9/iss1/8 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Clara High Technology Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POLYMERASE CHAIN REACTION (PCR): THE SECOND GENERATION OF DNA ANALYSIS METHODS TAKES THE STAND Kamrin T. MacKnightt TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................... 288 BASIC GENETICS AND DNA REPLICATION ................. 289 FORENSIC DNA ANALYSIS ................................ 292 Direct Sequencing ....................................... 293 Restriction FragmentLength Polymorphism (RFLP) ...... 294 Introduction .......................................... 294 Technology ........................................... 296 Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) ....................... 300 H istory ............................................... 300 Technology .......................................... -

Mittelalterliche Migrationen Als Gegenstand Der "Genetic History"

Jörg Feuchter Mittelalterliche Migrationen als Gegenstand der ‚Genetic History‘ Zusammenfassung Genetic History untersucht historische Fragen mit der Quelle DNA. Migrationen sind ihr Hauptgegenstand, woraus sich eine große Bedeutung für die Mediävistik ergibt. Doch bis vor kurzem waren Historiker nicht beteiligt. Der Beitrag gibt eine Definition der neuen Dis- ziplin (), untersucht die Rolle des Konzeptes Migration in der Populationsgenetik () und beschreibt den Stand der Migrationsforschung in der Mediävistik (). Anschließend gibt er einen kurzen Überblick über die von der Genetic History untersuchten Migrationsräu- me (), betrachtet exemplarisch zunächst eine Studie zur angelsächsischen Migration nach Britannien () und dann ein aktuelles Projekt, in dem erstmals ein Mediävist die Leitung innehat (). Der Beitrag endet mit einigen allgemeinen Beobachtungen und Postulaten (). Keywords: Genetik; DNA; Mittelalter; Angelsachsen; Langobarden; Völkerwanderung. Genetic History is the study of historical questions with DNA as a source. Migrations are its main subject. It is thus very relevant to Medieval Studies. Yet until recently historians have not been involved. The contribution provides a definition of the new discipline (), explores the role of migration as a concept in Population Genetics () and describes the state of migration studies in Medieval History (). It then sets out for an overview of medieval migratory areas studied by Genetic History () and takes an exemplary look first () at a study on Anglo-Saxon migration to Britain and later () at a current project where for the first time a medieval historian has taken the lead. The contribution ends () with some general observations and stipulations. Keywords: Genetics; DNA; Middle Ages; Anglo-Saxons; Lombards; Migration Period. Danksagung: Der Verfasser dankt Prof. Dr. Veronika Lipphardt (University College Frei- burg) und der von ihr von bis geleiteten Nachwuchsgruppe Twentieth Century Felix Wiedemann, Kerstin P. -

Jeffreys Alec

Alec Jeffreys Personal Details Name Alec Jeffreys Dates 09/01/1950 Place of Birth UK (Oxford) Main work places Leicester Principal field of work Human Molecular Genetics Short biography To follow Interview Recorded interview made Yes Interviewer Peter Harper Date of Interview 16/02/2010 Edited transcript available See below Personal Scientific Records Significant Record sets exists Records catalogued Permanent place of archive Summary of archive Interview with Professor Alec Jeffreys, Tuesday 16 th February, 2010 PSH. It’s Tuesday 16 th February, 2010 and I am talking with Professor Alec Jeffreys at the Genetics Department in Leicester. Alec, can I start at the beginning and ask when you were born and where? AJ. I was born on the 9 th January 1950, in Oxford, in the Radcliffe Infirmary and spent the first six years of my life in a council house in Headington estate in Oxford. PSH. Were you schooled in Oxford then? AJ. Up until infant’s school and then my father, who worked at the time in the car industry, he got a job at Vauxhall’s in Luton so then we moved off to Luton. So that was my true formative years, from 6 to 18, spent in Luton. PSH. Can I ask in terms of your family and your parents in particular, was there anything in the way of a scientific background, had either of them or any other people in the family been to university before. Or were you the first? AJ. I was the first to University, so we had no tradition whatsoever of going to University. -

Mapping Our Genes—Genome Projects: How Big? How Fast?

Mapping Our Genes—Genome Projects: How Big? How Fast? April 1988 NTIS order #PB88-212402 Recommended Citation: U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, Mapping Our Genes-The Genmne Projects.’ How Big, How Fast? OTA-BA-373 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, April 1988). Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 87-619898 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402-9325 (order form can be found in the back of this report) Foreword For the past 2 years, scientific and technical journals in biology and medicine have extensively covered a debate about whether and how to determine the function and order of human genes on human chromosomes and when to determine the sequence of molecular building blocks that comprise DNA in those chromosomes. In 1987, these issues rose to become part of the public agenda. The debate involves science, technol- ogy, and politics. Congress is responsible for ‘(writing the rules” of what various Federal agencies do and for funding their work. This report surveys the points made so far in the debate, focusing on those that most directly influence the policy options facing the U.S. Congress, The House Committee on Energy and Commerce requested that OTA undertake the project. The House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, the Senate Com- mittee on Labor and Human Resources, and the Senate Committee on Energy and Natu- ral Resources also asked OTA to address specific points of concern to them. Congres- sional interest focused on several issues: ● how to assess the rationales for conducting human genome projects, ● how to fund human genome projects (at what level and through which mech- anisms), ● how to coordinate the scientific and technical programs of the several Federal agencies and private interests already supporting various genome projects, and ● how to strike a balance regarding the impact of genome projects on international scientific cooperation and international economic competition in biotechnology. -

Science in Court

www.nature.com/nature Vol 464 | Issue no. 7287 | 18 March 2010 Science in court Academics are too often at loggerheads with forensic scientists. A new framework for certification, accreditation and research could help to heal the breach. o the millions of people who watch television dramas such as face more legal challenges to their results as the academic critiques CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, forensic science is an unerring mount. And judges will increasingly find themselves refereeing Tguide to ferreting out the guilty and exonerating the inno- arguments over arcane new technologies and trying to rule on the cent. It is a robust, high-tech methodology that has all the preci- admissibility of the evidence they produce — a struggle that can sion, rigour and, yes, glamour of science at its best. lead to a body of inconsistent and sometimes ill-advised case law, The reality is rather different. Forensics has developed largely which muddies the picture further. in isolation from academic science, and has been shaped more A welcome approach to mend- by the practical needs of the criminal-justice system than by the ing this rift between communities is “National leadership canons of peer-reviewed research. This difference in perspective offered in a report last year from the is particularly has sometimes led to misunderstanding and even rancour. For US National Academy of Sciences important example, many academics look at techniques such as fingerprint (see go.nature.com/WkDBmY). Its given the highly analysis or hair- and fibre-matching and see a disturbing degree central recommendation is that the interdisciplinary of methodological sloppiness. -

Genetic Variation of Genes for Xenobiotic-Metabolizing

Journal of Human Genetics (2009) 54, 440–449 & 2009 The Japan Society of Human Genetics All rights reserved 1434-5161/09 $32.00 www.nature.com/jhg ORIGINAL ARTICLE Genetic variation of genes for xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes and risk of bronchial asthma: the importance of gene–gene and gene–environment interactions for disease susceptibility Alexey V Polonikov, Vladimir P Ivanov and Maria A Solodilova The aim of our pilot study was to evaluate the contribution of genes for xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes (XMEs) for the development of bronchial asthma. We have genotyped 25 polymorphic variants of 18 key XME genes in 429 Russians, including 215 asthmatics and 214 healthy controls by a polymerase chain reaction, followed by restriction fragment length polymorphism analyses. We found for the first time significant associations of CYP1B1 V432L (P¼0.045), PON1 Q192R (P¼0.039) and UGT1A6 T181A (P¼0.025) gene polymorphisms with asthma susceptibility. Significant P-values were evaluated through Monte-Carlo simulations. The multifactor-dimensionality reduction method has obtained the best three-locus model for gene–gene interactions between three loci, EPHX1 Y113H, CYP1B1 V432L and CYP2D6 G1934A, in asthma at a maximum cross-validation consistency of 100% (P¼0.05) and a minimum prediction error of 37.8%. We revealed statistically significant gene–environment interactions (XME genotypes–smoking interactions) responsible for asthma susceptibility for seven XME genes. A specific pattern of gametic correlations between alleles of XME genes was found in asthmatics in comparison with healthy individuals. The study results point to the potential relevance of toxicogenomic mechanisms of bronchial asthma in the modern world, and may thereby provide a novel direction in the genetic research of the respiratory disease in the future. -

Pharmacogenetics: a Tool for Identifying Genetic Factors in Drug Dependence and Response to Treatment

RESEARCH REVIEW—PHARMACOGENETICS • 17 Pharmacogenetics: A Tool for Identifying Genetic Factors in Drug Dependence and Response to Treatment harmacogenetics research looks at variations in the human genome and ways in which genetic factors might influence Phow individuals respond to drugs. The authors review basic principles of pharmacogenetics and cite findings from several gene-phenotype studies to illustrate possible associations between genetic variants, drug-related behaviors, and risk for drug dependence. Some gene variants affect responses to one drug; others, to various drugs. Pharmacogenetics can inform medica- tion development and personalized treatment strategies; challenges lie along the pathway to its general use in clinical practice. Margaret Mroziewicz, M.Sc.1 ubstance dependence is a complex psychiatric disorder that develops in Rachel F. Tyndale, Ph.D. 1,2,3 response to a combination of environmental and genetic risk factors and 1 Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology drug-induced effects (Ho et al., 2010). The strong genetic basis of depen- University of Toronto S Toronto, Canada dence is supported by family, adoption, and twin studies, which demonstrate 2Department of Psychiatry substantial heritability, estimated to be about 50 percent (Uhl et al., 2008). The University of Toronto Toronto, Canada evidence suggests that no single variant accounts for a major portion of this risk, 3Centre for Addiction and Mental Health but that variations in many genes each contribute a small amount. Toronto, Canada Pharmacogenetics is the study of the genetic factors that influence drug response and toxicity. In this review, we briefly state the basic principles of pharmacoge- netics and then provide examples of discoveries that demonstrate the impact of genetic variation on drug dependence, drug effects, and drug-induced behaviors. -

Metal-Organic Frameworks: the New All-Rounders in Chemistry Research

Issue 2 | January 2019 | Half-Yearly | Bangalore RNI No. KARENG/2018/76650 Rediscovering School Science Page 8 Metal-organic frameworks: The new all-rounders in chemistry research A publication from Azim Premji University i wonder No. 134, Doddakannelli Next to Wipro Corporate Office Sarjapur Road, Bangalore — 560 035. India Tel: +91 80 6614 9000/01/02 Fax: +91 806614 4903 www.azimpremjifoundation.org Also visit the Azim Premji University website at www.azimpremjiuniversity.edu.in A soft copy of this issue can be downloaded from http://azimpremjiuniversity.edu.in/SitePages/resources-iwonder.aspx i wonder is a science magazine for school teachers. Our aim is to feature writings that engage teachers (as well as parents, researchers and other interested adults) in a gentle, and hopefully reflective, dialogue about the many dimensions of teaching and learning of science in class and outside it. We welcome articles that share critical perspectives on science and science education, provide a broader and deeper understanding of foundational concepts (the hows, whys and what nexts), and engage with examples of practice that encourage the learning of science in more experiential and meaningful ways. i wonder is also a great read for students and science enthusiasts. Editors Ramgopal (RamG) Vallath Chitra Ravi Editorial Committee REDISCOVERING SCHOOL SCIENCE Anand Narayanan Hridaykant Dewan Jayalekshmy Ayyer Navodita Jain Editorial Radha Gopalan As a child growing up in rural Kerala, my chief entertainment was reading: mostly Rajaram Nityananda science, history of science and, also, biographies of scientists. To me, science Richard Fernandes seemed pure and uncluttered by politicking. I thought of scientists as completely Sushil Joshi rational beings, driven only by a desire to uncover the mysteries of the universe. -

Final Programme

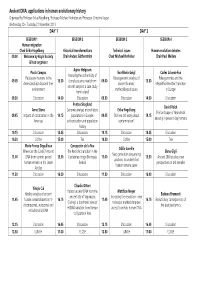

Ancient DNA: applications in human evolutionary history Organised by Professor Erika Hagelberg, Professor Michael Hofreiter and Professor Christine Keyser Wednesday 20 - Thursday 21 November 2013 DAY 1 DAY 2 SESSION 1 SESSION 2 SESSION 3 SESSION 4 Human migration Chair Erika Hagelberg Historical transformations Technical issues Human evolution debates 09.00 Welcome by Royal Society Chair Anders Götherström Chair Michael Hofreiter Chair Paul Mellars & lead organiser Agnar Helgason Paula Campos Eva-Maria Geigl Carles Lalueza-Fox Assessing the authenticity of Pleistocene humans in the Palaeogenomic analysis of Paleogenomics and the 09.05 13.30 clonal sequence reads from 09.00 13.30 Americans/East Asia and their ancient humans: Mesolithic-Neolithic transition ancient samples: a case study environment methodological issues in Europe from Iceland 09.30 Discussion 14.00 Discussion 09.30 Discussion 14.00 Discussion Pontus Skoglund David Reich Anne Stone Genomic analysis of prehistoric Erika Hagelberg The landscape of Neandertal 09.45 Impacts of colonization in the 14.15 populations in Europe: 09.45 Shall we still worry about 14.15 ancestry in present-day humans Americas authentication and population contamination? history 10.15 Discussion 14.45 Discussion 10.15 Discussion 14.45 Discussion 10.30 Coffee 15.00 Tea 10.30 Coffee 15.00 Tea Marie-France Deguilloux Concepción de la Rua Odille Loreille Where are the Caribs? Ancient The Neolithic transition in the Elena Gigli Next generation sequencing 11.00 DNA from ceramic period 15.30 Cantabrian fringe -

Transposon Variants and Their Effects on Gene Expression in Arabidopsis

Transposon Variants and Their Effects on Gene Expression in Arabidopsis Xi Wang, Detlef Weigel*, Lisa M. Smith* Department of Molecular Biology, Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology, Tu¨bingen, Germany Abstract Transposable elements (TEs) make up the majority of many plant genomes. Their transcription and transposition is controlled through siRNAs and epigenetic marks including DNA methylation. To dissect the interplay of siRNA–mediated regulation and TE evolution, and to examine how TE differences affect nearby gene expression, we investigated genome- wide differences in TEs, siRNAs, and gene expression among three Arabidopsis thaliana accessions. Both TE sequence polymorphisms and presence of linked TEs are positively correlated with intraspecific variation in gene expression. The expression of genes within 2 kb of conserved TEs is more stable than that of genes next to variant TEs harboring sequence polymorphisms. Polymorphism levels of TEs and closely linked adjacent genes are positively correlated as well. We also investigated the distribution of 24-nt-long siRNAs, which mediate TE repression. TEs targeted by uniquely mapping siRNAs are on average farther from coding genes, apparently because they more strongly suppress expression of adjacent genes. Furthermore, siRNAs, and especially uniquely mapping siRNAs, are enriched in TE regions missing in other accessions. Thus, targeting by uniquely mapping siRNAs appears to promote sequence deletions in TEs. Overall, our work indicates that siRNA–targeting of TEs may influence removal of sequences from the genome and hence evolution of gene expression in plants. Citation: Wang X, Weigel D, Smith LM (2013) Transposon Variants and Their Effects on Gene Expression in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet 9(2): e1003255.