Post-Dissolution Liabilities of Shareholders and Directors for Claims Against Dissolved Corporations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Judgment Claims in Receivership Proceedings*

JUDGMENT CLAIMS IN RECEIVERSHIP PROCEEDINGS* JOHN K. BEACH Connecticuf Supreme Court of Errors In view of the importance of the subject it is unfortunate that so few of the reported cases on equitable receiverships of corporations have dealt in any comprehensive way with the principles underlying the administrating of the fund for the benefit of creditors. The result is that controversy has outstripped authoritative decision, and the subject is unsettled. To this generalization an exception must be noted in respect of the special topic of the application of current rail- way income to current expenses, before the payment of mortgage 1 indebtedness. On another disputed topic, the provability of imma.ure claims, the law, or at least the right principle of decision, has been settled, by the notable opinion of Judge Noyes in Pennsylvania Steel Company v. New York City Railway Company,2 followed and rein- forced by that of Mr. Justice Holmes in William Filene'sSons Company v. Weed.' Notwithstanding these important exceptions, the dearth of authority on the general subject is such that Judge Noyes refers to a case cited in his opinion as "almost the only case in which rules have "been formulated with respect to the provability of claims against "insolvent corporations."4 Upon the particular phase of the subject here discussed, the decisions are to some extent in conflict, and no attempt seems to have been made in text books or decisions to examine the question in the light of principle. Black, for example, dismisses the subject by saying it. is generally conceded that a receiver and the corporation whose property is under his charge "are so far in privity that a judgment against the * This paper deals only with judgments against the defendant in the receiver- ship, regarded as evidence of the validity and amount of the judgment creditor's claims for dividends to be paid out of the fund in the receiver's hands. -

Self-Represented Creditor

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS A GUIDE FOR THE SELF-REPRESENTED CREDITOR IN A BANKRUPTCY CASE June 2014 Table of Contents Subject Page Number Legal Authority, Statutes and Rules ....................................................................................... 1 Who is a Creditor? .......................................................................................................................... 1 Overview of the Bankruptcy Process from the Creditor’s Perspective ................... 2 A Creditor’s Objections When a Person Files a Bankruptcy Petition ....................... 3 Limited Stay/No Stay ..................................................................................................... 3 Relief from Stay ................................................................................................................ 4 Violations of the Stay ...................................................................................................... 4 Discharge ............................................................................................................................. 4 Working with Professionals ....................................................................................................... 4 Attorneys ............................................................................................................................. 4 Pro se ................................................................................................................................................. -

UK (England and Wales)

Restructuring and Insolvency 2006/07 Country Q&A UK (England and Wales) UK (England and Wales) Lyndon Norley, Partha Kar and Graham Lane, Kirkland and Ellis International LLP www.practicallaw.com/2-202-0910 SECURITY AND PRIORITIES ■ Floating charge. A floating charge can be taken over a variety of assets (both existing and future), which fluctuate from 1. What are the most common forms of security taken in rela- day to day. It is usually taken over a debtor's whole business tion to immovable and movable property? Are any specific and undertaking. formalities required for the creation of security by compa- nies? Unlike a fixed charge, a floating charge does not attach to a particular asset, but rather "floats" above one or more assets. During this time, the debtor is free to sell or dispose of the Immovable property assets without the creditor's consent. However, if a default specified in the charge document occurs, the floating charge The most common types of security for immovable property are: will "crystallise" into a fixed charge, which attaches to and encumbers specific assets. ■ Mortgage. A legal mortgage is the main form of security interest over real property. It historically involved legal title If a floating charge over all or substantially all of a com- to a debtor's property being transferred to the creditor as pany's assets has been created before 15 September 2003, security for a claim. The debtor retained possession of the it can be enforced by appointing an administrative receiver. property, but only recovered legal ownership when it repaid On default, the administrative receiver takes control of the the secured debt in full. -

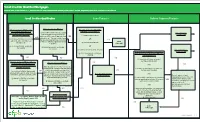

QM Small Creditor Flow Chart

SSmmaallll CCrreeddiittoorr QQuuaalliiffiieedd MMoorrttggaaggeess RReefflleeccttss rruulleess iinn eeffffeecctt oonn MMaarrcchh 11,, 22002211 bbuutt ddooeess nnoott rreefflleecctt aammeennddmmeennttss mmaaddee bbyy tthhee EEccoonnoommiicc GGrroowwtthh,, RReegguullaattoorryy RReelliieeff,, aanndd CCoonnssuummeerr PPrrootteeccttiioonn AAcctt.. Type of Compliance Presumption: SmSmaallll CCrreeddiitotorr QQuuaalliifificcaatitioonn Loan Features Balloon Payment Features Underwriting Points and Fees Portfolio Higher-Priced Loan Did you do ALL of the following?: Did you and your affiliates: Did you and your affiliates who Does the loan have ANY of the Rebuttable Presumption At the time of consummation: are creditors that extended following characteristics?: (1) Consider and verify the consumer’s YES Applies Extend 2,000 or fewer first-lien, closed- Does the loan amount fall within the following covered transactions during the Potential Small debt obligations and income or assets? STOP end residential mortgages that are points-and-fees limits? Was the loan subject to forward last calendar year have: (1) negative amortization; Creditor QM [via § 1026.43(c)(7), (e)(2)(v)]; = Non-Small Creditor QM (QM is presumed to comply subject to ATR requirements in the last YES commitment? AND YES YES = Non-Balloon-Payment QM with ATR requirements if calendar year? You can exclude loans Points-and-fees caps (adjusted annually) Assets below $2 billion (as annually OR AND it’s a higher-priced loan, but YES [§ 1026.43(e)(5)(i)(C), (f)(1)(v)] that you originated and kept in portfolio consumers can rebut the adjusted) at the end of the last STOP If Loan Amount ≥ $100,000, then = 3% of total or that your affiliate originated and kept (2) interest-only features; (2) Calculate the consumer’s monthly presumption by showing calendar year? = Non-QM If $100,000 > Loan Amount ≥ $60,000, then = $3,000 in portfolio. -

Creditor Control of Corporations Operating Receiverships Corporate Reorganizations Chester Rohrlich

Cornell Law Review Volume 19 Article 3 Issue 1 December 1933 Creditor Control of Corporations Operating Receiverships Corporate Reorganizations Chester Rohrlich Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Chester Rohrlich, Creditor Control of Corporations Operating Receiverships Corporate Reorganizations, 19 Cornell L. Rev. 35 (1933) Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol19/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CREDITOR CONTROL OF CORPORATIONS; OPERATING RECEIVERSHIPS; COR- PORATE REORGANIZATIONS* CHESTER RoHRmicnt A corporation is, on a smaller scale (in some instances on a larger scale), like the political state, in that beneath the cloak of its unity there is a continuous, at times active but more frequently passive, struggle for power among the various groups in interest. Some of these groups, such as the public that deals with it or the employees who work for it, have as yet achieved only the the barest minimum of legal right to control its destinies.' In the arena of the law, the traditional conflict is between the stockholders2 and the creditors. There is an increasing convergence of interest between these two groups as the former become more and more "investors" rather than entrepreneurs, and the latter less and less inclined, or able, to stand on the letter of their bond'3 both are in the last analysis dependent *This article is the substance of one of the chapters of the author's forthcoming book THE LAW AND PRACTICE OF CORPORATE CONTROL. -

Lesson 13: Dissolution, Liquidation and Extinction of Companies

LESSON 13: DISSOLUTION, LIQUIDATION AND EXTINCTION OF COMPANIES SUMMARY: 1.-Dissolution a) Causes b) Requirements and procedure c) Advertising 2.-Liquidation a) Liquidation bodies b) Procedure 3.-Extinction 4.- Vocabulary 1.-Dissolution A company can be considered, on one hand, a contract signed by at least two people and, on the other hand, a legal person which has several legal relationships with third parties. In order to protect those third parties, as well as the company itself and its partners, the final extinction of a company should go through two different stages. The first one would be dissolution, in which the company continues to be a legal person but ceases its commercial purpose and starts the liquidation. The second one would be liquidation, in which the company compensates its credits and debts vis-à-vis third parties and distributes the corporate assets resulting from the liquidation among all shareholders. Once the liquidation procedure is finished, the registered entries of the dissolved company will be cancelled. From this moment, the company will be extinguished. CAUSES: Three different types of causes can be distinguished: a) Causes which lead to an automatic dissolution of the company (art. 360 LSC) Expiry of the term established in the articles of association of the company. In order to avoid dissolution in this case, a general meeting resolution will be required to extend the duration of the company agreement. When the company has not been converted, dissolved or its capital share has not been increased within a year after being obligated to reduce its share capital below the minimum amount established by law. -

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT of NEW YORK for PUBLICATION ------X in Re: RICHARD HARTLEY Chapter 7 and KARA L

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK FOR PUBLICATION --------------------------------------------------------X In re: RICHARD HARTLEY Chapter 7 and KARA L. HARTLEY, No. 09-37770 (CGM) Debtors. --------------------------------------------------------X JENNIFER ESPOSITO, Plaintiff, v. Adv. Pro. No. 10-9055 (CGM) RICHARD HARTLEY and KARA L. HARTLEY, Defendants. --------------------------------------------------------X APPEARANCES: DRAKE LOEB HELLER KENNEDY GOGERTY GABA & RODD, PLLC 555 Hudson Valley Avenue Suite 100 New Windsor, NY 12553 By: Stuart Kossar Attorneys for Plaintiff, Jennifer Esposito GREHER LAW OFFICES, P.C. 1161 Little Britain Road Suite B New Windsor, NY 12553 By: Warren Greher Attorney for the Defendants, Richard and Kara Hartley MEMORANDUM DECISION GRANTING PLAINTIFF’S MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGEMENT The plaintiff brings this adversary proceeding to except from discharge a judgment obtained against the defendants’ deli and catering business, Hartley’s Catering, Inc. (“Hartley’s Catering”). Because the defendants dissolved the corporation without giving plaintiff notice and opportunity to enforce her judgment against it, the defendants are jointly and severally liable for Page 1 of 12 on the judgment. The debt is non-dischargeable as property obtained by false pretenses, pursuant to section 523(a)(2)(A) and for failure to list the plaintiff in the petition pursuant to 523(a)(3). Background On November 13 2003, Hartley’s Catering was incorporated in the state of New York. Stmt. Material Facts ¶ 1. On February 21, 2008, the New York State Commission of the Division of Human Rights found Hartley’s Catering d/b/a Schlesinger’s Deli Depot, liable to the plaintiff in the amount of $300,000. Stmt. Material Facts ¶ 50. -

Overview of the Fdic As Conservator Or Receiver

September 26, 2008 OVERVIEW OF THE FDIC AS CONSERVATOR OR RECEIVER This memorandum is an overview of the receivership and conservatorship authority of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (the “FDIC”). In view of the many and complex specific issues that may arise in this context, this memorandum is necessarily an overview, but it does give particular reference to counterparty issues that might arise in the case of a relatively large complex bank such as a significant regional bank and outlines elements of the FDIC framework which differ from a corporate bankruptcy. This memorandum has three parts: (1) background on the legal framework governing FDIC resolutions, highlighting changes and developments since the 1990s; (2) an outline of six distinctive aspects of the FDIC approach with comparison to the bankruptcy law provisions; and (3) a final section illustrating issues and uncertainties in the FDIC resolutions process through a more detailed review of two examples – treatment of loan securitizations and participations, and standby letters of credit.1 Relevant additional materials include: the pertinent provisions of the Federal Deposit Insurance (the "FDI") Act2 and FDIC rules3, statements of policy4 and advisory opinions;5 the FDIC Resolution Handbook6 which reflects the FDIC's high level description of the receivership process, including a contrast with the bankruptcy framework; recent speeches of FDIC Chairman 1 While not exhaustive, these discussions are meant to be exemplary of the kind of analysis that is appropriate in analyzing any transaction with a bank counterparty. 2 Esp. Section 11 et seq., http://www.fdic.gov/regulations/laws/rules/1000- 1200.html#1000sec.11 3 Esp. -

Company Voluntary Arrangements: Evaluating Success and Failure May 2018

Company Voluntary Arrangements: Evaluating Success and Failure May 2018 Professor Peter Walton, University of Wolverhampton Chris Umfreville, Aston University Dr Lézelle Jacobs, University of Wolverhampton Commissioned by R3, the insolvency and restructuring trade body, and sponsored by ICAEW This report would not have been possible without the support and guidance of: Allison Broad, Nick Cosgrove, Giles Frampton, John Kelly Bob Pinder, Andrew Tate, The Insolvency Service Company Voluntary Arrangements: Evaluating Success and Failure About R3 R3 is the trade association for the UK’s insolvency, restructuring, advisory, and turnaround professionals. We represent insolvency practitioners, lawyers, turnaround and restructuring experts, students, and others in the profession. The insolvency, restructuring and turnaround profession is a vital part of the UK economy. The profession rescues businesses and jobs, creates the confidence to trade and lend by returning money fairly to creditors after insolvencies, investigates and disrupts fraud, and helps indebted individuals get back on their feet. The UK is an international centre for insolvency and restructuring work and our insolvency and restructuring framework is rated as one of the best in the world by the World Bank. R3 supports the profession in making sure that this remains the case. R3 raises awareness of the key issues facing the UK insolvency and restructuring profession and framework among the public, government, policymakers, media, and the wider business community. This work includes highlighting both policy issues for the profession and challenges facing business and personal finances. 2 Company Voluntary Arrangements: Evaluating Success and Failure Executive Summary • The biggest strength of a CVA is its flexibility. • Assessing the success or failure of CVAs is not straightforward and depends on a number of variables. -

Liquidators, Receivers and Examiners Their Duties and Powers

Liquidators, Receivers and Examiners Their duties and powers A quick guide Introduction We have produced this information booklet to explain the powers, duties and responsibilities of liquidators, receivers and examiners under the Companies Acts. What are liquidations, receiverships and examinerships? The liquidation of a company is also known as ‘winding up’ a company. The process takes the company out of existence in an orderly way by paying debts from any available assets. Receivership is used by banks or other lenders to sell a company asset that was promised to them if the company failed to repay its loan as agreed. Examinership is a process that protects a company from its creditors (the people to whom it owes money) while efforts are being made to keep it running as a going concern. What are liquidators, receivers and examiners? A liquidator is the person who winds up a company. A receiver is the person who sells particular company assets on behalf of a lender. Where a loan is secured on a company’s entire business, a ‘receiver manager’ can be appointed as manager of the business during the receivership. Once a receiver raises enough money to pay back the debt, their job is finished. Liquidators, Receivers and Examiners Their duties and powers Examiners consider if a company can be saved and, if it can, they prepare the rescue plan. Who can act as liquidators, receivers or examiners? Liquidators, receivers and examiners do not need to have any specific qualifications under the law. However, they are usually practising accountants. To make sure that liquidators, receivers and examiners work independently of the company, they cannot be: • a director or employee of the company; or • a family member, partner or employee of a director. -

Principles of the Law of Family Dissolution: Analysis and Recommendations*

ALI CHAPTER - FMT_2.DOC 10/01/01 11:54 AM PRINCIPLES OF THE LAW OF FAMILY DISSOLUTION: ANALYSIS AND RECOMMENDATIONS* CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTORY MATERIALS Topic 1 Summary Overview of the Remaining Chapters Chapter Two** I. The Current Legal Context The primary challenge in shaping the law that governs allocation of re- sponsibility for children is to determine how to facilitate thoughtful planning by cooperative parents while minimizing the harm to children who are caught in a cycle of conflict. Several unavoidable tensions in the law’s objectives and its de- sign complicate this task. a. Predictability v. individualized decision-making. There is a significant ten- sion in custody law between the goals of predictability and individualization. The predictability of outcomes helps to reduce litigation, as well as strategic and manipulative behavior by parents. Predictable outcomes are insufficient, how- ever, unless they are also sound. And it is difficult to imagine sound outcomes in custody cases unless the diverse range of circumstances in which family breakdown occurs are taken into account. Predictability is important, and so is the customization of a result to the individual, sometimes unique, facts of a case. Copyright © The American Law Institute (ALI). Reproduced with ALI permission from the uned- ited, unpublished final manuscript. All rights reserved. Editorial changes are possible before publi- cation. The final, official text of the Principles of the Law of Family Dissolution is scheduled to be pub- lished late in 2001. Earlier drafts in the ALI project, as well as the final text when it becomes available, may be ordered from the ALI’s Customer Service Department: www.ali.org; telephone 800-253-6397; fax 215-243-1664. -

Irish Examinership: Post-Eircom a Look at Ireland's Fastest and Largest

A look at Ireland’s fastest and largest restructuring through examinership and the implications for the process Irish examinership: post-eircom A look at Ireland’s fastest and largest restructuring through examinership and the implications for the process* David Baxter Tanya Sheridan A&L Goodbody, Dublin A&L Goodbody [email protected] The Irish telecommunications company eircom recently successfully concluded its restructuring through the Irish examinership process. This examinership is both the largest in terms of the overall quantum of debt that was restructured and also the largest successful restructuring through examinership in Ireland to date. The speed with which the restructuring of this strategically important company was concluded was due in large part to the degree of pre-negotiation between the company and its lenders before the process commenced. The eircom examinership demonstrated the degree to which an element of pre-negotiation can compliment the process. The advantages of the process, having been highlighted through the eircom examinership, might attract distressed companies from other EU jurisdictions to undertake a COMI shift to Ireland in order to avail of this process. he eircom examinership was notable for both the Irish High Court just 54 days after the companies Tsize of this debt restructuring and the speed in entered examinership. which the process was successfully concluded. In all, This restructuring also demonstrates the advantages €1.4bn of a total debt of approximately €4bn was of examinership as a ‘one-stop shop’: a flexible process written off the balance sheets of the eircom operating that allows for both the write-off of debt and the change companies.