The Australian Grocery Sector: Structurally Irredeemable?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 First Quarter Retail Sales Results 362 KB

2017 First Quarter Retail Sales Results 26 October 2016 First Quarter Sales ($m) 2017 2016 Variance % Food & Liquor1,2 7,850 7,631 2.9 Convenience1,3 1,549 1,795 (13.7) Total Coles 9,399 9,426 (0.3) Bunnings Australia & New Zealand 2,659 2,476 7.4 Bunnings UK & Ireland 554 n.a. n.a. Home Improvement4,5 3,213 2,476 29.8 Kmart1 1,249 1,123 11.2 Target6 643 776 (17.1) Department Stores 1,892 1,899 (0.4) Officeworks4 461 429 7.5 Refer to Appendix Three for footnotes. Wesfarmers Limited today announced its retail sales results for the first quarter of the 2017 financial year. Managing Director Richard Goyder said that the sales performance of the Group’s retail businesses, with the exception of Target, built on the strong sales growth achieved in the prior corresponding period. “Coles’ headline food and liquor sales increased by 2.9 per cent for the quarter, building on the strong growth achieved in the previous corresponding period,” Mr Goyder said. “Coles continues to invest in value, service and quality, supported by ongoing efficiency improvements across the business. “Bunnings Australia and New Zealand achieved total sales growth of 7.4 per cent during the quarter, extending its very strong performance despite an impact from the stock liquidation activities of the Masters business. In the United Kingdom and Ireland, good progress continues to be made to reshape the business, with sales of £320 million ($554 million) for the quarter, in line with expectations. “Kmart recorded strong sales growth of 11.2 per cent, with a continued focus on lowest prices and the customer experience delivering growth across all categories. -

Kaufland Australia Proposed Store Mornington, Melbourne Economic Impact Assessment

Kaufland Australia Proposed store Mornington, Melbourne Economic Impact Assessment November 2018 Prepared by: Anthony Dimasi, Managing Director – Dimasi & Co [email protected] Prepared for Kaufland Australia Table of contents Executive summary 1 Introduction 5 Section 1: The supermarket sector – Australia and Victoria 6 Section 2: Kaufland Australia – store format and offer 13 Section 3: Economic Impact Assessment 20 3.1 Site location and context 21 3.2 Trade area analysis 23 3.3 Competition analysis 27 3.4 Estimated sales potential 28 3.5 Economic impacts 30 3.6 Net community benefit assessment 43 Executive summary The Supermarkets & Grocery Stores category is by far the most important retail category in Australia. Total sales recorded by Supermarkets & Grocery Stores as measured by the Australian Bureau of Statistics have increased from $64.5 billion at 2007 to $103.7 billion at 2017, recording average annual growth of 4.9% per annum – despite the impacts of the global financial crisis (GFC). Over this past decade the category has also increased its share of total Australian retail sales from 31.3% to 33.7%. For Victoria, similar trends are evident. Supermarkets and grocery stores’ sales have increased over the past decade at a similar rate to the national average – 4.5% versus 4.9%. The share of total retail sales directed to supermarkets and grocery stores by Victorians has also increased over this period, from 31.6% at 2007 to 32.8% at 2017. Given the importance of the Supermarkets & Grocery Stores category to both the Victorian retail sector and Victorian consumers, the entry of Kaufland into the supermarket sector brings with it enormous potential for significant consumer benefits, as well as broader economic benefits. -

Supermarket Refrigeration Going Natural

cover story >>> SEAN McGOWAN REPORTS Supermarket refrigeration going natural In 2005, Coles Supermarkets opened its first ‘environmental concept’ supermarket featuring a cascade carbon dioxide refrigeration system. Two years on the technology has undergone significant improvement to better serve the local market, while internationally it promises to receive widespread adoption by the world’s retail heavyweights, as Sean McGowan reports. Supermarket refrigeration accounts for a significant 1% of Australia’s total electricity consumption, and this figure is reported to be higher in Europe and the United States. Therefore, its not surprising to find supermarket chains worldwide clamoring to adopt new technology which promises to cut their energy costs, while at the same time, address their corporate responsibilities to the environment and the communities who shop with them. The knight in shining armour looks set to be carbon dioxide (CO2) refrigeration systems, which are often used in a cascade design with fluorocarbon refrigerants such as R507 or R134a. A cascade system using ammonia is also on the agenda according to one of Australia’s leading supermarket refrigeration specialists, Frigrite Refrigeration. “We have traveled the world investigating system design and have developed solutions that best suit the Australian market. We installed the first CO2 systems in Australia, with another four systems installed in new supermarkets since,” says Andrew Reid, national account manager for Frigrite. “Due to economic constraints, the cascade CO2 systems installed in Australia best suit the energy and environmental expectations, however, further development is underway in finding improvements to the current concepts, which may involve a fundamental system design change and alternate refrigerants to those currently being used.” Reid says supermarket chains have acknowledged the importance of meeting environmental and community expectations as the general awareness of these two aspects increases. -

Coles Operations Graduate Program Streams

Distribution Centres Our Coles Distribution Centres play an important role moving quality products through our supply chain, to provide extraordinary shopping experiences for our customers. We work hard to make life easier, safer and more sustainable across our network, as well as maintain the availability and quality of our products for our customers. Working with our logistics partners, we are reducing our environmental footprint through more efficient fleet movements. We are also ensuring customers are provided with quality, safe products by conducting selected quality checks when produce arrives at our fresh produce distribution centres, with additional checks for chilled products. What's in it for you? The Distribution Centre offers you the opportunity to learn new skills in various departments, broadening your understanding of how our business works on a larger scale. Most importantly, your skills of communication, leadership, responsibility, resilience, flexibility and teamwork will be heightened from being part of our diverse team, setting you up for a successful career in supply chain. Coles Supermarkets Coles Supermarkets is a national full-service supermarket retailer operating more than 800 stores across Australia. Our purpose is to sustainably feed all Australians to help them live healthier, happier lives. We’re an essential part of communities right across the country, with our family of 120,000 team members helping 21 million customers every week. With such a big responsibility, we rely on our brilliant team to operate with pace and passion and drive a people first culture, focussed on delighting our customers. Coles Supermarkets has an Australian-first sourcing policy to provide our customers with quality Australian-grown fresh produce. -

COMPANY INTRODUCTION Coles Group Ltd (CGL) Is Australia's

COMPANY INTRODUCTION Coles Group Ltd (CGL) is Australia’s dominant retailing company with an estimated market share of more than 20 percent of all retail sales in Australia. Its major businesses include Australia’s largest department store chain, largest grocery-supermarket chain, and the largest discount chains. In addition, it is a major player in food and liquor retailing, office supplies and apparel. The Product Portfolio of Coles Group include – (Source: Goggle Images viewed on 6th January 2007) - 1 - Food and Liquor: The Food division includes full-line Coles Supermarkets, Bi-Lo discount Supermarkets which are increasingly being merged into Coles supermarkets. The Liquor division includes First Choice Liquor Superstores, Liquorland, Vintage Cellars and Liquorland Hotel Group. Liquorland also operates an online liquor shopping service, Liquorland Direct. (Source: www.coles.com.au) Kmart: Kmart offers an extensive range of products such as apparel, toys, sporting goods, bedding, kitchenware, outdoor furniture, barbecues, music, video, car care, electrical appliances and Kmart Tyre & Auto Service business. Kmart operates 185 stores and 275 Kmart Tyre & Auto Service sites across Australia and New Zealand. (Source: www.coles.com.au) Target: Target has an extensive range of apparel and accessories, home wares, bed linen and décor, cosmetics, fragrances, health and beauty products and a full range of toys, games and entertainment. Target has 259 stores located across Australia. (Source: www.coles.com.au) Officeworks: Officeworks caters specifically for the needs of small to medium businesses, home offices and students, with over 7,000 office products all under one roof, located in 95 stores across Australia. (Source: www.coles.com.au) Coles Express: CML has a network of 599 Coles Express locations across Australia in an alliance with Shell. -

2018 Sustainability Report Su

WESFARMERS SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2018 CONTENTS Our Report 3 Sustainability at Wesfarmers 4 Our material issues 5 Managing Director’s welcome Our Principles Our Businesses People Bunnings 6 Safety 41 Bunnings 8 People development 11 Diversity Coles 45 Coles Sourcing 15 Suppliers Department Stores 18 Ethical sourcing and human rights 54 Kmart 58 Target Community 26 Community contributions Officeworks 29 Product safety 63 Officeworks Environment Industrials 31 Climate change resilience 67 Chemicals, Energy & Fertilisers 34 Waste and water use 70 Industrial and Safety 73 Resources Governance 37 Robust governance 74 Other businesses This is an edited extract of our 2018 Sustainability Report. Our full sustainability report contains numerous case studies and data available for download. It is prepared in accordance with the Global Reporting Initiatives Standards and assured by Ernst & Young. It is available at sustainability.wesfarmers.com.au Sustainability Report 2018 2 Our Report SUSTAINABILITY AT WESFARMERS At Wesfarmers we believe long-term value creation is only possible WESFARMERS CONSIDERS SUSTAINABILITY if we play a positive role in the communities we serve. Sustainability is about understanding and managing the ways we impact our AS AN OPPORTUNITY TO DRIVE STRONG AND community and the environment, to ensure we continue to create LONG-TERM SHAREHOLDER RETURNS value in the future. Wesfarmers is committed to minimising our footprint and to This Sustainability Report presents Wesfarmers Limited delivering solutions that help our customers and the community (ABN 28 008 984 049) and its wholly owned subsidiary companies’* do the same. We are committed to making a contribution to the sustainability performance for the year ended 30 June 2018, how we communities in which we operate through strong partnerships performed, the value we created and our plans for the future. -

Hypermarket Lessons for New Zealand a Report to the Commerce Commission of New Zealand

Hypermarket lessons for New Zealand A report to the Commerce Commission of New Zealand September 2007 Coriolis Research Ltd. is a strategic market research firm founded in 1997 and based in Auckland, New Zealand. Coriolis primarily works with clients in the food and fast moving consumer goods supply chain, from primary producers to retailers. In addition to working with clients, Coriolis regularly produces reports on current industry topics. The coriolis force, named for French physicist Gaspard Coriolis (1792-1843), may be seen on a large scale in the movement of winds and ocean currents on the rotating earth. It dominates weather patterns, producing the counterclockwise flow observed around low-pressure zones in the Northern Hemisphere and the clockwise flow around such zones in the Southern Hemisphere. It is the result of a centripetal force on a mass moving with a velocity radially outward in a rotating plane. In market research it means understanding the big picture before you get into the details. PO BOX 10 202, Mt. Eden, Auckland 1030, New Zealand Tel: +64 9 623 1848; Fax: +64 9 353 1515; email: [email protected] www.coriolisresearch.com PROJECT BACKGROUND This project has the following background − In June of 2006, Coriolis research published a company newsletter (Chart Watch Q2 2006): − see http://www.coriolisresearch.com/newsletter/coriolis_chartwatch_2006Q2.html − This discussed the planned opening of the first The Warehouse Extra hypermarket in New Zealand; a follow up Part 2 was published following the opening of the store. This newsletter was targeted at our client base (FMCG manufacturers and retailers in New Zealand). -

Supply-Change.Org Company Launch List

Supply-Change.Org Company Launch List Is your company on this list? Contact Supply Change to request a profile preview, now through March 25, 2015. Adani Wilmar Burberry Emami Biotech Adidas Campbell's Etablissements Fr. Colruyt AEON Cargill Eurostar Agropalma Carrefour Farm Frites Ahlstrom Casino Fazer Group Ajinomoto Catalyst Paper Ferrero Trading Aldi Nord Cefetra Findus Group Aldi Sud Cémoi Florin Almacenes Exito Cencosud General Mills Amcor Cérélia Ginsters Arla Foods Coca-Cola Godrej Industries Arnott's Biscuits Coles Supermarkets Golden Agri-Resources ASDA Colgate-Palmolive Goodman Fielder Asia Pacific Resources Compass Group Greenergy International International Limited ConAgra Foods Grupo André Maggi Asia Pulp and Paper Co-op Clean Co. Grupo JD Associated British Foods Coop Norway Gucci Auchan Coop Sweden H & M August Storck Coop Switzerland Hain Celestial Aviko Co-operative Group Haribo Avon CostCo HarperCollins Axfood Cranswick Harry's Barilla CSM Bakery Supplies Hasbro Barry Callebaut Food Dai Nippon Printing Co. Heineken International Manufacturers Europe Dairy Farm International Heinz BASF Danone Henkel Bayer Dansk Supermarked Hershey Company Beijing Hualian Danzer Hewlett-Packard Best Buy Delhaize Hillshire Brands BillerudKorsnäs Doctor's Associates Holmen Bimbo Dohle Handelsgruppe Holding ICA Bongrain Dow IGA Boots UK Drax Group Iglo Foods Group Brambles Dunkin' Brands Igor Novara Brioche Pasquier Cerqueux Dupont Ikea British Airways Ecover Inditex British Sky Broadcasting Elanco International Flavors & Fragrances Bunge -

Annual Report 2020

Issue 07 OCTOBER 2020 The 2020 MGATMA Annual Report is inside! RISK • CONTROL • MONITOR Managing the risk of COVID-19 See page 12 YOUR INDUSTRY NEWS PROVIDED BY MGA INDEPENDENT RETAILERS 3 Contents 5 CEO welcome OUR MISSION 6 The case for a national COVID-19 plan The mission of MGA Independent Retailers is to deliver the best possible 8 Preventative maintenance: Keeping your refrigeration industry specific business support equipment in shape services to independent grocery, liquor, 8 New eftpos API program goes live hardware and associate store members. 9 Drakes Supermarkets – A trusted place to shop 10 Heineken® 0.0 leading from the front MGA NATIONAL 11 What does it take to ensure SMEs are digital ready? SUPPORT OFFICE 12 RISK • CONTROL • MONITOR Managing the risk of Suite 5, 1 Milton Parade, Malvern, Victoria, 3144 COVID-19: What does an inspector look for? P: 03 9824 4111 • F: 03 9824 4022 14 Wynns Coonawarra Estate’s Cath Kidman 2020 GT Wine [email protected] • www.mga.asn.au Viticulturist of the year Freecall: 1800 888 479 16 Asahi sells five liquor brands to Heinekin© 17 Overseas licences now accepted as proof of age RETAILER DIRECTORS 18 Iconic West End Brewery to be shut down Debbie Smith (President): Queensland 19 At 87 and in the same job for 61 years, Effie may just be Grant Hinchcliffe (Vice President): Tasmania Adelaide’s most loyal worker Graeme Gough: New South Wales 21 Michael Daly: Victoria 2019 ANNUAL REPORT Financial Year 2020 Ross Anile: Western Australia » Carmel Goldsmith: New South Wales » Benefits of membership -

A Public Interest Assessment

A Public Interest Assessment Applicant: Woolworths Group Limited Application: Application for Liquor Store Licence Proposed Store: BWS – Beer Wine Spirits Inglewood CULLEN MACLEOD Lawyers Level 2, 95 Stirling Highway NEDLANDS WA 6009 Telephone: (08) 9389 3999 Facsimile: (08) 9389 1511 Reference: SN:190339 TABLE OF CONTENTS Details of the Application ....................................................... 1 1 About the Application 1 2 About the Proposed Store, the Supermarket and the Centre 1 2.1 The Proposed Store 1 2.2 The Supermarket 4 2.3 Centre 6 3 Details of the business to be operated at the Proposed Store 7 3.1 About the Applicant 7 3.2 Features of the Proposed Store and manner of trade 7 3.3 Security measures 11 4 About the Public Interest Assessment 13 4.1 The legislative requirements 13 4.2 Addressing the Public Interest 13 5 Key Public Interest Factors in the Application 14 5.1 Key features and factors of the Locality 14 5.2 Demographic Profile 19 5.3 Crime and health data 20 5.4 Field and site investigations 21 5.5 Offence, annoyance, disturbance, etc 23 5.6 Existing Licensed Premises 24 5.7 Consumer Requirement and Proper Development 36 5.8 Market Survey 39 Submissions and conclusion .................................................. 42 6 Submissions 42 6.1 Relevant legal principles 42 6.2 Key factual matters 44 7 Conclusion 46 General ................................................................................ 47 8 Definitions, source data and copyright 47 8.1 Definitions 47 8.2 Source data 47 8.3 Copyright 48 Annexures ............................................................................ 50 PIA Final i Details of the Application 1 About the Application (a) The Applicant has made an application to the Licensing Authority for the grant of a liquor store licence for premises be located in a new shopping centre in Inglewood, Western Australia. -

GAIN Report Global Agriculture Information Network

Foreign Agricultural Service GAIN Report Global Agriculture Information Network Voluntary Report - public distribution Date: 12/10/2002 GAIN Report #AS2042 Australia Product Brief Confectionery Products 2002 Approved by: Andrew C. Burst U.S. Embassy Prepared by: Australian Centre for Retail Studies Report Highlights: Within the global confectionery market, Australia is ranked 11th for sugar confectionery consumption and 9th for chocolate. Nine out of ten people regularly consume confectionery from both the chocolate and sugar confectionery categories. Approximately 55 percent of confectionery sales are through supermarkets, with the remaining 45 percent sold through outlets such as milk-bars, convenience stores and specialty shops. New products are introduced fairly regularly to the Australian confectionery market; however highly innovative products are less common and this may be an area that offers opportunities for U.S. exporters to be successful in this market. In 2001, Australia was the 15th largest export market for U.S. confectionery products. Includes PSD changes: No Includes Trade Matrix: No Unscheduled Report Canberra [AS1], AS This report was drafted by consultants: The Australian Centre for Retail Studies Monash University PO Box 197 Caulfield East VIC 3145 Tel: +61 3 9903 2455 Fax: +61 3 9903 2099 Email: [email protected] Disclaimer: As a number of different sources were used to collate market information for this report, there are areas in which figures are slightly different. The magnitude of the differences is, in most cases, small and the provision of the data, even though slightly different, is to provide the U.S. exporter with the best possible picture of the Australian Confectionery Sector where omission may have provided less than that. -

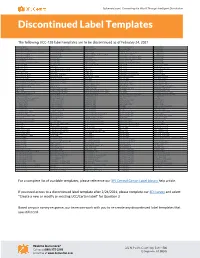

Discontinued Label Templates

3plcentral.com | Connecting the World Through Intelligent Distribution Discontinued Label Templates The following UCC-128 label templates are to be discontinued as of February 24, 2021. AC Moore 10913 Department of Defense 13318 Jet.com 14230 Office Max Retail 6912 Sears RIM 3016 Ace Hardware 1805 Department of Defense 13319 Joann Stores 13117 Officeworks 13521 Sears RIM 3017 Adorama Camera 14525 Designer Eyes 14126 Journeys 11812 Olly Shoes 4515 Sears RIM 3018 Advance Stores Company Incorporated 15231 Dick Smith 13624 Journeys 11813 New York and Company 13114 Sears RIM 3019 Amazon Europe 15225 Dick Smith 13625 Kids R Us 13518 Harris Teeter 13519 Olympia Sports 3305 Sears RIM 3020 Amazon Europe 15226 Disney Parks 2806 Kids R Us 6412 Orchard Brands All Divisions 13651 Sears RIM 3105 Amazon Warehouse 13648 Do It Best 1905 Kmart 5713 Orchard Brands All Divisions 13652 Sears RIM 3206 Anaconda 13626 Do It Best 1906 Kmart Australia 15627 Orchard Supply 1705 Sears RIM 3306 Associated Hygienic Products 12812 Dot Foods 15125 Lamps Plus 13650 Orchard Supply Hardware 13115 Sears RIM 3308 ATTMobility 10012 Dress Barn 13215 Leslies Poolmart 3205 Orgill 12214 Shoe Sensation 13316 ATTMobility 10212 DSW 12912 Lids 12612 Orgill 12215 ShopKo 9916 ATTMobility 10213 Eastern Mountain Sports 13219 Lids 12614 Orgill 12216 Shoppers Drug Mart 4912 Auto Zone 1703 Eastern Mountain Sports 13220 LL Bean 1702 Orgill 12217 Spencers 6513 B and H Photo 5812 eBags 9612 Loblaw 4511 Overwaitea Foods Group 6712 Spencers 7112 Backcountry.com 10712 ELLETT BROTHERS 13514 Loblaw