Temporal Registers in the Construction of Life Forms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

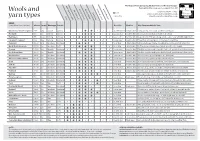

Fleece Characteristics and Yarn Types

The Natural Fibre Company, Blacker Yarns and Blacker Designs 4-ply (Sportweight) Fleece Characteristics Pennygillam Way, Launceston, Cornwall PL15 7PJ Aran (Medium) Chunky (Bulky) better Worsted better Woollen DK (Worsted) Telephone: 01566 777635 best Guernsey and yarn types Email: [email protected] Website: www.thenaturalfibre.co.uk possible Lace BREED good purpose (sorted alphabetically) rarity* staple length fleece weight micron lustre fibre type handle blended* of blend* Blend suggestions THE NATURAL FIBRE COMPANY Black Welsh Mountain native 6-10cm(3-4”) 1.25-2kg(3-4lbs) 32-35 no medium soft 3 Blue-faced Leicester no 8-15cm(3-6”) 1-2kg(2-4lbs) 24-26.5 semi fine soft 3 3 possible variety silk, flax, Black BFL (rare) Boreray Critical 5-10cm(2-4”) 1-2kg(2-4lbs) 25-40 no double medium 3 possible extend Soay Castlemilk Moorit Vulnerable 5-8cm(2-3”) 1kg (2.2lbs) 30-31.5 no fine medium 3 yes improve silk, alpaca Corriedale/Merino/Falkland no 7.5-12.5cm(3-5”) 4.5-6kg(10-13lbs) 18-25 no fine soft 3 3 possible variety silk, flax, Manx, Hebridean, BWM Cotswold At Risk 17.5-30cm(7-12”) 4-7kg(9-15lbs) 34-40 yes medium medium 3 Devon & Cornwall Longwool Vulnerable 17.5-30cm(7-12”) 6-9kg(12-20lbs) 40+ yes coarse strong 3 3 possible improve Mule Galway rare 11.5-19cm(4.5-7.5”) 2.5-3.5kg(5.5-7.7lbs) 30+ semi medium medium 3 3 Gotland rare in UK 8-12cm(3-5”) 1-4kg(2-8lbs) 26-35 yes medium soft 3 possible variety silk, Merino, Corriedale Hebridean native 5-15cm(2-6”) 1-2kg(2-4lbs) 35+ some strong strong 3 yes improve Manx Loagthan, mohair -

Ewe Lamb in the Local Village Show Where Most of the Exhibits Were Taken from the Fields on the Day of the Show

Cotswold Sheep Society Newsletter Registered Charity No. 1013326 ` Autumn 2011 Hampton Rise, 1 High Street, Meysey Hampton, Gloucestershire, GL7 5JW [email protected] www.cotswoldsheepsociety.co.uk Council Officers Chairman – Mr. Richard Mumford Vice-Chairman – Mr. Thomas Jackson Secretary - Mrs. Lucinda Foster Treasurer- Mrs. Lynne Parkes Council Members Mrs. M. Pursch, Mrs. C. Cunningham, The Hon. Mrs. A. Reid, Mr. R Leach, Mr. D. Cross. Mr. S. Parkes, Ms. D. Stanhope Editors –John Flanders, The Hon. Mrs. Angela Reid Pat Quinn and Joe Henson discussing the finer points of……….? EDITORIAL It seems not very long ago when I penned the last editorial, but as they say time marches on and we are already into Autumn, certainly down here in Wales the trees have shed many of their leaves, in fact some began in early September. In this edition I am delighted that Joe Henson has agreed to update his 1998 article on the Bemborough Flock and in particular his work with the establishment to the RBST. It really is fascinating reading and although I have been a member of the Society since 1996 I have learnt a huge amount particularly as one of my rams comes from the RASE flock and Joe‟s article fills in a number of gaps in my knowledge. As you will see in the AGM Report, Pat Quinn has stepped down as President and Robert Boodle has taken over that position with Judy Wilkie becoming Vice President. On a personal basis, I would like to thank Pat Quinn for her willing help in supplying articles for the Newsletter and the appointment of Judy Wilkie is a fitting tribute to someone who has worked tirelessly over many years for the Society – thank you and well done to you both. -

Gwartheg Prydeinig Prin (Ba R) Cattle - Gwartheg

GWARTHEG PRYDEINIG PRIN (BA R) CATTLE - GWARTHEG Aberdeen Angus (Original Population) – Aberdeen Angus (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol) Belted Galloway – Belted Galloway British White – Gwyn Prydeinig Chillingham – Chillingham Dairy Shorthorn (Original Population) – Byrgorn Godro (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol). Galloway (including Black, Red and Dun) – Galloway (gan gynnwys Du, Coch a Llwyd) Gloucester – Gloucester Guernsey - Guernsey Hereford Traditional (Original Population) – Henffordd Traddodiadol (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol) Highland - Yr Ucheldir Irish Moiled – Moel Iwerddon Lincoln Red – Lincoln Red Lincoln Red (Original Population) – Lincoln Red (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol) Northern Dairy Shorthorn – Byrgorn Godro Gogledd Lloegr Red Poll – Red Poll Shetland - Shetland Vaynol –Vaynol White Galloway – Galloway Gwyn White Park – Gwartheg Parc Gwyn Whitebred Shorthorn – Byrgorn Gwyn Version 2, February 2020 SHEEP - DEFAID Balwen - Balwen Border Leicester – Border Leicester Boreray - Boreray Cambridge - Cambridge Castlemilk Moorit – Castlemilk Moorit Clun Forest - Fforest Clun Cotswold - Cotswold Derbyshire Gritstone – Derbyshire Gritstone Devon & Cornwall Longwool – Devon & Cornwall Longwool Devon Closewool - Devon Closewool Dorset Down - Dorset Down Dorset Horn - Dorset Horn Greyface Dartmoor - Greyface Dartmoor Hill Radnor – Bryniau Maesyfed Leicester Longwool - Leicester Longwool Lincoln Longwool - Lincoln Longwool Llanwenog - Llanwenog Lonk - Lonk Manx Loaghtan – Loaghtan Ynys Manaw Norfolk Horn - Norfolk Horn North Ronaldsay / Orkney - North Ronaldsay / Orkney Oxford Down - Oxford Down Portland - Portland Shropshire - Shropshire Soay - Soay Version 2, February 2020 Teeswater - Teeswater Wensleydale – Wensleydale White Face Dartmoor – White Face Dartmoor Whitefaced Woodland - Whitefaced Woodland Yn ogystal, mae’r bridiau defaid canlynol yn cael eu hystyried fel rhai wedi’u hynysu’n ddaearyddol. Nid ydynt wedi’u cynnwys yn y rhestr o fridiau prin ond byddwn yn eu hychwanegu os bydd nifer y mamogiaid magu’n cwympo o dan y trothwy. -

First Report on the State of the World's Animal Genetic Resources"

"First Report on the State of the World’s Animal Genetic Resources" (SoWAnGR) Country Report of the United Kingdom to the FAO Prepared by the National Consultative Committee appointed by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). Contents: Executive Summary List of NCC Members 1 Assessing the state of agricultural biodiversity in the farm animal sector in the UK 1.1. Overview of UK agriculture. 1.2. Assessing the state of conservation of farm animal biological diversity. 1.3. Assessing the state of utilisation of farm animal genetic resources. 1.4. Identifying the major features and critical areas of AnGR conservation and utilisation. 1.5. Assessment of Animal Genetic Resources in the UK’s Overseas Territories 2. Analysing the changing demands on national livestock production & their implications for future national policies, strategies & programmes related to AnGR. 2.1. Reviewing past policies, strategies, programmes and management practices (as related to AnGR). 2.2. Analysing future demands and trends. 2.3. Discussion of alternative strategies in the conservation, use and development of AnGR. 2.4. Outlining future national policy, strategy and management plans for the conservation, use and development of AnGR. 3. Reviewing the state of national capacities & assessing future capacity building requirements. 3.1. Assessment of national capacities 4. Identifying national priorities for the conservation and utilisation of AnGR. 4.1. National cross-cutting priorities 4.2. National priorities among animal species, breeds, -

Secretariat VSS (Association of Special Sheep Breeds)

There are 45 varieties registered with the VSS. And 14 of these have an official recognition (reference date June 2019) Balwen Welsh Mountain Jacobschaap The internationally Barbados Black Belly Karakul recognized studbooks: Bentheimer Landschaap Kreiner Steinschaf Cambridge Black Welsh Mountain Leicester Longwool Castlemilk Moorit Blue Faced Leicester Lleyn Coburger Fuchs Border Leicester Manx Loaghtan Devon&Cornwall Longwool Brilschaap Oxford Down Herdwick British Texel Persian Blackhhead Leicester Longwool Bruine Bergschaap Poll Dorset Norfolk Horn Charmoise Racka Portland Dorper Romney Ryeland Dorset Horn Rouge d’Ouest Scottish Blackface Duitse witkop Shropshire Shetland Duitse zwartkop South Down Solognote Hebridean Wensleydale Longwool Walliser Schwarznase Heideschnucke Wolmerino Wiltshire Horn www.vssschapen.nl 573 45 35 96, @: @: 96, 35 45 573 - 031 0 el: t [email protected] Netherlands The Ruurlo, LV 7261 4, Hengeloseweg Wassink, Karin Mrs. Secretariat VSS Breeds) Sheep Special of (Association 0120 The VSS (Association of Special Sheep Breeds) Unity in Diversity The VSS is a national association. Around 600 members own 45 varieties. Some breeds are special, but not endangered, other breeds rare even in the country of origin, e.g. the Devon and Cornwall Longwool and the Manx Loagtan. The size of the breed groups is also running from 110 holders/breeders of Walliser Schwarznase to 1 breeder from, for example, the Shropshire or 1 holder of the Heideschnucke. The VSS presents itself with its own sheep collection at various events, where sheep from individual members and breed groups can also be found. The diversity between the sheep breeds can then be clearly observed, from small to large, from thick-in-the-wool to self-moulting, from curl to style, from rough to fine wool, from unhorned to multi-horned and in every conceivable sheep color. -

Life, Time and the Organism

Life, time and the organism: Temporal registers in the construction of life forms Abstract In this paper, we articulate how time and temporalities are involved in the making of living things. For these purposes, we draw on an instructive episode concerning Norfolk Horn sheep. We attend to historical debates over the nature of the breed, whether it is extinct or not, and whether presently living exemplars are faithful copies of those that came before. We argue that there are features to these debates that are important to understanding contemporary configurations of life, time and the organism, especially as these are articulated within the field of synthetic biology. In particular, we highlight how organisms are configured within different material and semiotic assemblages that are always structured temporally. While we identify three distinct structures, namely the historical, phyletic and molecular registers, we do not regard the list as exhaustive. We also highlight how these structures are related to the care and value invested in the organisms at issue. Finally, because we are interested ultimately in ways of producing time, our subject matter requires us to think about historiographical practice reflexively. This draws us into dialogue with other scholars interested in time, not just historians, but also philosophers and sociologists, and into conversations with them about time as always multiple and never an inert background. Words: 209 Keywords Breeding; Organism; Synthetic biology; Time; Value Acknowledgments Palladino was funded by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, under a Marie Sklodowska-Curie Individual Fellowship (657750). Berry was funded by the European Research Council through a Consolidator Grant (616510-ENLIFE). -

George Garrard's Livestock Models by JULIET OLUTTON-BR.OCK

! ...... !i George Garrard's Livestock Models By JULIET OLUTTON-BR.OCK A series of plaster models of domestic pigs, cattle, and sheep that were made by George Garrard between about 179o and 181o has been held in the British Museum (Natural History) since the !! beginning of this century. In view oftheincreasing concern for the conservation ofrare breeds of livestock it is perhaps an opportune time to publish a description of these models, for they por- tray the favoured breeds at a crucial period in the history oflivestock improvement. Many o~'the breeds which were the most commercially successful in 18oo (when oxen were still used for il ploughing, and the production of tallow was a major industry) are at tile present day either extinct or changed out of all recognition, although a few of the old breeds that have survived unchanged are now playing a new economic role in "farm parks" where they are exhibited as relics of a past agricultural age. EORGE GAP,.RARD (176o-1826) was a painter who turned his atten- t-ion to the making of casts and models of many subjects, but mainly of domestic animals. In this project he was sponsored by the fifth Duke of Bedford, who was the first president of the Smithfield Club (founded hi I798), and by the third Earl of Egremont, as well as by other members of the Board of Agri- culture. Garrard called his house in Hanover Square, London, "The Agricultural Museum," and from there he sold his models. In 1798 Garrard published a statement in the Annals of Agriculture to advertise his models; parts of this statement are quoted as follows: Mr Garrard is now preparing the models from the best specimens that can be procured, under the inspection of those noblemen (the Duke of Bedford and the Earl of Egremont); and he proposes to publish a set of models, to consist of a bull, a cow, and an ox, of the Devonshire, Herefordshire, and Holdemesse cattle, upon a scale front nature, of two inches and a quarter to a foot. -

Wools and Yarn Types

4-ply (Sportweight) The Natural Fibre Company, Blacker Yarns and Blacker Designs Aran (Medium) Chunky (Bulky) better Worsted better Woollen Pennygillam Way, Launceston, Cornwall PL15 7PJ DK (Worsted) Wools and Telephone: 01566 777635 Guernsey best Email: [email protected] yarn types Lace possible Website: www.thenaturalfibre.co.uk BREED (sorted from coarse to fine) micron lustre fibre type handle Good for Bad for Key Characteristics In Yarn THE NATURAL FIBRE COMPANY Devon & Cornwall Longwool 40+ yes coarse strong 3 3 garden twine next to skin Long, strong and coarse, good for carpets too Herdwick 35+ no strong strong 3 accessories next to skin Coarse, kempy but great heathered colours Hebridean 35+ some strong strong 3 accessories next to skin A good dark off-black, strong, lambs can be very soft with slight lustre Leicester Longwool 35+ yes strong strong 3 outer wear next to skin Nice when worsted spun, and using coloured fibre Cotswold 34-40 yes medium medium 3 near skin detail/cable Strong, lustrous, creamy, long staple good for worsted, lambs fine Black Welsh Mountain 32-35 no medium soft 3 near skin detail/cable Soft and a good dark almost black, versatile, nice handle Boreray 25-40 no double medium 3 outer wear next to skin Double coat, fine and coarse but feels soft, good natural colour range North Ronaldsay 25-40 no double medium 3 outer wear detail/cable Double coat, fine and coarse but feels soft, good natural colour range Norfolk Horn 32-35 no medium medium 3 outer wear next to skin Good, bouncy general purpose -

Index to Pages Page GDPR Policy

Index to Pages Page GDPR Policy ......................................................................................................... 2 Maedi Visna Notice ............................................................................................... 2 Bio-Security ............................................................................................................ 3 HOW TO MAKE YOUR ENTRY ............................................................................ 3 Sheep - British Charollais, Jacob ........................................................................... 4 Suffolk, Texel, Shropshire ...................................................................................... 5 Beltex ..................................................................................................................... 6 *Southdown Sheep National Show* ..................................................................... 6 Valais Blacknose, Zwartbles, AOB Continental Sheep, AOB Native Sheep ......... 7 Interbreed, Butchers Lambs................................................................................... 8 Rare Breeds .......................................................................................................... 9 Rare Breed Sheep - Primitive Breeds .................................................................. 10 Rare Breed Sheep - Heath & Hill Breeds ............................................................ 11 Rare Breed Sheep - Longwool Breeds ............................................................... -

Traditional, Native and Rare Breeds Livestock

Schedule Tenth Annual Show & Sale of Traditional, Native and Rare Breeds Livestock Incorporating the Shropshire Sheep Breeders’ National Show and Sale Event to include a Poultry Sale On Sunday 28th July 2019 At Shrewsbury Auction Centre Bowman Way, Shawbury Turn, Battlefield, Shrewsbury SY4 3DR, Tel: 01743 462 620 Website:www.hallsgb.com Closing Date for Shropshire entries 28th June 2019 all other livestock 14th July 2019 Livestock Entries to: Mrs A Schofield Brookfield Farm, Sproston Green, Holmes Chapel, Cheshire CW4 7LN Email:[email protected] Tel: 01477 533256 Mobile: 077 405 303 81 Poultry sales are catalogued separately Entry forms/Catalogues will be available from Halls Show Classes The following classes will be offered, rosettes and cards to 3rd in each class and a Champion and Reserve in each Section. Classes may be amalgamated depending on entries. Eligible Breeds: Cattle Sheep Llanwenog Pigs Albion Balwen Manx Loaghtan British Lop Beef Shorthorn Black Welsh Mountain Norfolk Horn Berkshire Belted Galloway Border Leicester North Ronaldsay British Landrace British White Boreray Oxford Down British Saddleback Gloucester Castlemilk Moorit Portland Large Black Irish Moiled Cotswold Ryeland Large White Longhorn Derbyshire Gritstone Shetland Tamworth Northern Dairy Devon and Cornwall Longwool Shropshire Gloucestershire Old Spots Shorthorn Devon Closewool Soay Middle White Red Poll Dorset Down South Wales Mountain Welsh Shetland Dorset Horn Southdown Oxford Sandy and Black Aberdeen Angus Greyface Dartmoor Teeswater (Original Population) Hebridean Wensleydale Traditional Hereford Hill Radnor Whiteface Dartmoor Lincoln Red(Original Jacob Whitefaced Woodland Population) Kerry Hill Wiltshire Horn White Park Leicester Longwool Welsh Mountain Pedigree Whitebred Shorthorn Lincoln Longwool Dairy Shorthorn (Original Population) Sheep Shropshire Breed – Judge: Les Newman, Norfolk 1. -

Encyclopedia of Historic and Endangered Livestock and Poultry

Yale Agrarian Studies Series James C. Scott, series editor 6329 Dohner / THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF HISTORIC AND ENDANGERED LIVESTOCK AND POULTRY BREEDS / sheet 1 of 528 Tseng 2001.11.19 14:07 Tseng 2001.11.19 14:07 6329 Dohner / THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF HISTORIC AND ENDANGERED LIVESTOCK AND POULTRY BREEDS / sheet 2 of 528 Janet Vorwald Dohner 6329 Dohner / THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF HISTORIC AND ENDANGERED LIVESTOCK AND POULTRY BREEDS / sheet 3 of 528 The Encyclopedia of Historic and Endangered Livestock and Poultry Breeds Tseng 2001.11.19 14:07 6329 Dohner / THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF HISTORIC AND ENDANGERED LIVESTOCK AND POULTRY BREEDS / sheet 4 of 528 Copyright © 2001 by Yale University. Published with assistance from the Louis Stern Memorial Fund. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Designed by Sonia L. Shannon Set in Bulmer type by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Printed in the United States of America by Jostens, Topeka, Kansas. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dohner, Janet Vorwald, 1951– The encyclopedia of historic and endangered livestock and poultry breeds / Janet Vorwald Dohner. p. cm. — (Yale agrarian studies series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-300-08880-9 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Rare breeds—United States—Encyclopedias. 2. Livestock breeds—United States—Encyclopedias. 3. Rare breeds—Canada—Encyclopedias. 4. Livestock breeds—Canada—Encyclopedias. 5. Rare breeds— Great Britain—Encyclopedias. -

Sheep and Pigs SCHEDULE of CLASSES & PRIZES MORETON-IN-MARSH and DISTRICT AGRICULTURAL and HORSE SHOW SOCIETY Company Limited by Guarantee, Registered in England No

Cattle, Sheep and Pigs SCHEDULE OF CLASSES & PRIZES MORETON-IN-MARSH AND DISTRICT AGRICULTURAL AND HORSE SHOW SOCIETY Company Limited by Guarantee, Registered in England No. 2397134 Registered Charity No. 900122. President Mr David Glaisyer CATTLE, SHEEP AND PIGS SECTIONS Show Chairman Katharine Loyd Vice Chairman Stephen Parkes Showground Director Clare Foster Secretaries Liz Day, Lynne Parkes & Martha Vipond ENTER ONLINE www.moretonshow.co.uk PAPER ENTRY TO SHOW OFFICE:- Moreton Show Office, Unit 5, Wychwood Court, Cotswold Business Village, London Road, Moreton in Marsh, Glos., GL56 0JQ Tel: 01608 651908 Fax: 01608 651878 Email: [email protected] ENTRIES CLOSE: All Sheep (including Fleeces), All Cattle (including Poll Herefords) and All Pigs: Friday 31st July Only entries for Cattle Young Handlers, Sheep Young Handlers, Goats Young Handlers, Pig Young Handlers, Mounted Fancy Dress, Dog Show and Terrier Racing are accepted on the Show day. ON-LINE ENTRY The Society operates an on-line entry system at www.moretonshow.co.uk. Please use this where at all possible. The advantages to exhibitors are: DISCOUNTED ENTRY FEES Immediate e-mail acknowledgement of entries and payment Ability to change or withdraw entries or classes up to the online closing date No stamps, envelopes or chasing the post – enter at any time of day or night Latest possible closing of entries Easier, quicker, cheaper and more accurate. Thank you The Society is most grateful to the Lord Dulverton and Mr. & Mrs. S. Righton for their kind co-operation in permitting the use of the showground and car park. THE SHIRE HORSE EMBLEM used by the Society was kindly donated by the late Rt.