Aileen Riggin, 1920 and 1924, Diving

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frank C. Graham, 1932 and 1936, Water Polo

OLYMPIAN ORAL HISTORY FRANK C. GRAHAM 1932 & 1936 OLYMPIC GAMES WATER POLO Copyright 1988 LA84 Foundation AN OLYMPIAN'S ORAL HISTORY INTRODUCTION Southern California has a long tradition of excellence in sports and leadership in the Olympic Movement. The Amateur Athletic Foundation is itself the legacy of the 1984 Olympic Games. The Foundation is dedicated to expanding the understanding of sport in our communities. As a part of our effort, we have joined with the Southern California Olympians, an organization of over 1,000 women and men who have participated on Olympic teams, to develop an oral history of these distinguished athletes. Many Olympians who competed in the Games prior to World War II agreed to share their Olympic experiences in their own words. In the pages that follow, you will learn about these athletes, and their experiences in the Games and in life as a result of being a part of the Olympic Family. The Amateur Athletic Foundation, its Board of Directors, and staff welcome you to use this document to enhance your understanding of sport in our community. ANITA L. DE FRANTZ President Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles Member Southern California Olympians i AN OLYMPIAN'S ORAL HISTORY METHODOLOGY Interview subjects include Southern California Olympians who competed prior to World War II. Interviews were conducted between March 1987, and August 1988, and consisted of one to five sessions each. The interviewer conducted the sessions in a conversational style and recorded them on audio cassette, addressing the following -

Code De Conduite Pour Le Water Polo

HistoFINA SWIMMING MEDALLISTS AND STATISTICS AT OLYMPIC GAMES Last updated in November, 2016 (After the Rio 2016 Olympic Games) Fédération Internationale de Natation Ch. De Bellevue 24a/24b – 1005 Lausanne – Switzerland TEL: (41-21) 310 47 10 – FAX: (41-21) 312 66 10 – E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.fina.org Copyright FINA, Lausanne 2013 In memory of Jean-Louis Meuret CONTENTS OLYMPIC GAMES Swimming – 1896-2012 Introduction 3 Olympic Games dates, sites, number of victories by National Federations (NF) and on the podiums 4 1896 – 2016 – From Athens to Rio 6 Olympic Gold Medals & Olympic Champions by Country 21 MEN’S EVENTS – Podiums and statistics 22 WOMEN’S EVENTS – Podiums and statistics 82 FINA Members and Country Codes 136 2 Introduction In the following study you will find the statistics of the swimming events at the Olympic Games held since 1896 (under the umbrella of FINA since 1912) as well as the podiums and number of medals obtained by National Federation. You will also find the standings of the first three places in all events for men and women at the Olympic Games followed by several classifications which are listed either by the number of titles or medals by swimmer or National Federation. It should be noted that these standings only have an historical aim but no sport signification because the comparison between the achievements of swimmers of different generations is always unfair for several reasons: 1. The period of time. The Olympic Games were not organised in 1916, 1940 and 1944 2. The evolution of the programme. -

Stirs Marimrough Oaeandmus

iNET PRESS RUN “I THE WEATHER. AVERAGE DAILY CIRCULATION Cloudy tonight. Probably show OP THE EVENING HERALD ers Tuesday. Little change in tem for the month of May, 1920. perature. 4,915 anthpBter lEufUing feraUi ____________________________ ______________________________________________ „ ----------------------------------------------- ------ --------------------- Cotaa- (TWELVE PAGES) PRICE THREE CENTS MANCHESTER, CONN., MONDAY, JUNE VOL. XLIV., NO. 223. Classified Adrertising on Page 8 Will Fly to Paris CHARCOAL PIT I Best Speller in U. S. OAEAN DM U S Sen. Warren, Dean of Congress, I TOBACCO BILL EXPEa SUNKEN RESUME PAPER Begins Eighty-third Year Today OF NATION NOW $.51 TO COME TO ‘TRAGEDY’ STIRS I Washington, June 21. — Thcj.common sense, a willingness to Ira- dean of congress in age and ser prove himself every day and a de IS SURFACETODAY MARIMROUGH M A W SOON vice, Sen. Francis E. Warren, Re sire to serve his nation first, his <» ■■ publican of W'yoming, today enter constitutents second, to the best of ed his eighty-third year, cne of the his ability.” oldest men ever to serve in the na While in the Senate, W'arren has More Money Goes to Lady This Evening or Tomorrow American Writing Paper tional legislature. seen eight men elected to the presi Little Town “ Agog” Over With a record of ne.arly 34 y.'irs dency. They were Presidents Harri in tue Senate, W.a;re i lias succeed son, Cleveland, McKinley, Roose Nicotine Than Ever Was Morning Set for Final Most Excitement in Years Company Reorganizes; ed to the post formerly held by velt, Taft, Wilson, Harding and •'Uncle Joe” Cannon. -

Aileen Riggin Soule: a Wonderful Life in Her Own Words

Aileen Riggin Soule: A Wonderful Life In her own words The youngest U.S. Olympic champion, the tiniest anywhere Olympic champion and the first women's Olympic springboard diving champion was Aileen Riggin. All these honors were won in the 1920 Olympics by Miss Riggin when she had just passed her 14th birthday. If no woman started earlier as an amateur champion, certainly no woman pro stayed on the top longer. Aileen Riggin never waited for opportunities to come her way. In 1924 at Paris, she became the only girl in Olympic history to win medals in both diving and swimming in the same Olympic Games (silver in 3 meter springboard and bronze in 100 meter backstroke). She turned pro in 1926, played the Hippodrome and toured with Gertrude Ederle’s Act for 6 months after her famous Channel swim. She made appearances at new pool openings and helped launch “learn to swim programs” around the world. She gave diving exhibitions, taught swimming, ledtured and wrote articles on fashion, sports, fitness and health for the New York Post and many of the leading magazines of her day. She also danced in the movie "Roman Scandals" starring Eddie Cantor and skated in Sonja Henie's film "One in a Million." She helped organize and coach Billy Rose's first Aquacade in which she also starred, at the 1937 Cleveland Exposition. She was truly a girl who did it all. When in 1996, while attending the Olympic Games in Atlanta as America’s oldest Olympic Gold medalist, she was asked if she still had any goals left in life, she said: "Yes. -

Sports and Physical Activities in Haemophiliacs: Results of a Clinical Study and Proposal for a New Classification

Central Journal of Hematology & Transfusion Bringing Excellence in Open Access Research Article *Corresponding author François Schved, Centre Régional de Traitement des Hémophiles, Hôpital Saint-Eloi 80 Avenue Augustin Sports and Physical Activities Fliche, 34295 Montpellier cedex 5, France, Tel: 33467337031; Fax: 3346733703; Email: Submitted: 04 August 2016 in Haemophiliacs: Results of a Accepted: 29 August 2016 Published: 30 August 2016 Clinical Study and Proposal for ISSN: 2333-6684 Copyright a New Classification © 2016 Schved OPEN ACCESS Jean-François Schved* Centre Régional de Traitement des Hémophiles, Hôpital Saint-Eloi, France Keywords • Haemophilia • Sports Abstract • Physical activities Sports and physical activities have long been contraindicated for haemophiliacs, • Haemorrhagic disease or they were restricted to a few activities such as swimming or walking. Recent progress in therapy has meant that haemophiliacs are now encouraged to participate in sports, although various guidelines have recommended that they avoid activities where risks outweigh benefits. In order to evaluate the type of sports undertaken by haemophiliacs and the benefits or risks associated with each sport, we conducted a questionnaire- based study. The questionnaire was sent to 124 patients. Among the 80 patients who responded, 71 (90%) currently participated in or had previously participated in a physical activity. Among them, 56 (70%) still played a sport. Nearly all sports were cited in the answers, the most frequently played by these 56 haemophiliacs being swimming (59%), cycling (44%), walking (43%), table tennis (33%), soccer (33%) and tennis (31%). Fifty-six patients reported a benefit in doing a sport: somatic (79%), psychological (80%) or social (62%). Thirty haemophiliacs (42%) reported at least one accident or incident linked to sport. -

Matthias APPENZELLER SUI)

Matthias APPENZELLER !SUI) Photo: LINTAO ZHANG / GETTY IMAGES FIna FIna 64 65 ONE STAR, ONE DISCIPLINE By Pedro ADREGA Editor-in-chief of Matthias APPENZELLER “I cannot make “FINA Aquatics World” magazine a living from high (SUI) diving only” No pressure, just enjoy the flight Can you make a living from high diving and the good company – that is or do you do something else profes- Matthias’s motto sionally? HIGH DIVING Sport in general in Switzerland doesn’t enjoy the high reputation it has in other countries. Especially for ‘marginalised’ New kid sports like diving and high diving, it is im- on the board At 26, Switzerland’s Matthias Appenzeller is one of the new faces to improve as a team. It is nice to see how everybody cares about the others. More- on the high diving circuit. Initially a 3m pool diver, he first entered over, the adrenaline rush after a new or a FINA competition in 2018, when he finished 16th in the World really difficult dive from 27m is amazing. Cup in Abu Dhabi (UAE). In 2019, he took part in the two major It is a feeling I feel nowhere else. meetings of the season, the World Championships in Gwangju Your first FINA high diving competition (KOR), where he was 21st, and the World Cup in China, where he was the World Cup in 2018. What was your feeling when you competed with achieved his best ranking so far, 15th. Then came COVID-19 and all these high diving stars? in the business world. I personally study the whole of 2020 was lost for competition. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 75-3121

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

An Experimental Testing of Ability and Progress in Swimming Walter J

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1933 An experimental testing of ability and progress in swimming Walter J. Osinski University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Osinski, Walter J., "An experimental testing of ability and progress in swimming" (1933). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1852. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1852 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. J883 DATE DUE UNIV. OF MASSACHUSETTS/AMHERST LIBRARY LD M268 1933 0825 "AN EXPERIMENTAL TESTING OP ABILITY AND PROGRESS IN SWIMMING." By Walter J. Osinskl "Thesis Submitted For Degree of Master of Science." Massachusetts State College, Amherst. 1933 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Page Terminology and definitions. •••• • 1 Limi -cation of exporiment • , • • ••«•••«• 5 Limitations of statistics. 4 ORIGIN AND HISTORY OF S'A'IEMING Historical excerpts.... • •••• 5 SURVEY OF SV.T .L ING LITERATURE History of testing in swimr.i5.ng «•••••..« 21 MATERIALS AND METHODS Development of tests* # •,••••••.,,* ..*•*••• 25 Test one. ••,,.».•• » »...•• »•• 26 Test two,... ............ •#••••##• 26 Test throe. •••• •••••#••••••••••••••»•• 27 Test four • ^ Test five 28 Test six, •*,,. ...*•••• • • 28 Method of procedure ,,,«• • • • 29 INTERPRETATION OF DATA Collection of data 34 Chart of entire experimental group,.,. • 37 Leg test of experimental group..... 38 Table I (leg test) 40 Graph I (leg test) 41 Page Collection of data (continuied) • Arm test of experimental group. ••••••• 42 Table II (arm tc st )••...••.«• 44 Graph II (arm test).. -

1972 SWIM-MASTER Volume I Table of Contents

1972 1972 SWIM-MASTER Volume I Table of Contents Page 2 Vol. I, No. 1, February 1972 3 Vol. I, No. 2, April 1972 4 Vol. I, No. 3, June 1972 5 Vol. I, No. 4, August 1972 6 Vol. I, No. 5, October 1972 7 Vol. I, No. 6, December 1972 8 Vol. I, Extra, December 1972 1 1972 1972 SWIM-MASTER Volume I Table of Contents Page Vol. I, No. 1, February 1972 1 Masters Invitational Produces Records and Fun (about First Official AAU Masters Swimming Meet, 1/1/1972) 2,8 Masters Swimming Notes (89 subscriptions so far; Terry Gathercole; Jack Kelly; Neville Alexander; Second Annual National AAU Aquatic Planning Conference -1/21-23/1972) 2 Swim-Master Editor, Associates, Regional Representatives 2 Ocean Swim (Galt Ocean Mile - some results) 2-5 1971 Masters Champions (1971 SCY Top Ten) 5 Calendar 6 Results - U of M Masters Swimming Meet, SCY, Coral Gables, FL - 12/12/1971 6 Regional Masters Swimming Meet, SCY, Bloomington, IN, - 12/11-12/1971 6 Fort Bragg Masters AG Invitational, SCY, Fort Bragg, NC, - 12/28/1971 6-7 ISHOF Invitational Masters Swim Championship Ft Lauderdale, FL - 1/1/1972 7 Mid Valley YMCA Masters Invitational, SCY, Van Nuys, CA, - 1/15/1972 7-8 Mission Viejo Nadadores Masters Invitational; SCY; Mission Viejo, CA - 1/29/1972 8 Cartoon "And You swim Butterfly!!!" 8 Masters Swimming Notes cont. from p.2 (Gus Clemens writes; meet results submissions; list of Masters swimmers; Bill Williams; Lt. cecilia Brown; Carl Yates; Charles Keeting ) 2 1972 1972 SWIM-MASTER Volume I Table of Contents Page Vol. -

USC's Mcdonald's Swim Stadium

2003-2004 USC Swimming and Diving USC’s McDonald’s Swim Stadium Home of Champions The McDonald’s Swim Stadium, the site of the 1984 Olympic swimming and diving competition, the 1989 U.S. Long Course Nationals and the 1991 Olympic Festival swimming and diving competition, is comprised of a 50-meter open-air pool next to a 25-yard, eight-lane diving well featuring 5-, 7 1/2- and 10- meter platforms. The home facility for both the USC men’s and women’s swimming and diving teams conforms to all specifications and requirements of the International Swimming Federation (FINA). One of the unusual features of the pool is a set of movable bulkheads, one at each end of the pool. These bulkheads are riddled with tiny holes to allow the water to pass Kennedy Aquatics Center, which houses locker features is the ability to show team names and through and thus absorb some of the waves facilities and coaches’ offices for both men’s scores, statistics, game times and animation. that crash into the pool ends. The bulkheads and women’s swimming and diving. It has a viewing distance of more than 200 can be moved, so that the pool length can be The Peter Daland Wall of Champions, yards and a viewing angle of more than 160 adjusted anywhere up to 50 meters. honoring the legendary USC coach’s nine degrees. The McDonald’s Swim Complex is located NCAA Championship teams, is located on the The swim stadium celebrated its 10th in the northwest corner of the USC campus, exterior wall of the Lyon Center. -

The International Swimming Hall of Fame's TIMELINE Of

T he In tte rn a t iio n all S wiim m i n g H allll o f F am e ’’s T IM E LI N E of Wo m e n ’’s Sw iim m i n g H i s t o r y 510 B.C. - Cloelia, a Roman maid, held hostage with 9 other Roman women by the Etruscans, leads a daring escape from the enemy camp and swims to safety across the Tiber River. She is the most famous female swimmer of Roman legend. 216 A.D. - The Baths of Caracalla, regarded as the greatest architectural and engineering feat of the Roman Empire and the largest bathing/swimming complex ever built opens. Swimming in the public bath houses was as much a part of Roman life as drinking wine. At first, bathing was segregated by gender, with no mixed male and female bathing, but by the mid second century, men and women bathed together in the nude, which lead to the baths becoming notorious for sexual activities. 600 A.D. - With the gothic conquest of Rome and the destruction of the Aquaducts that supplied water to the public baths, the baths close. Soon bathing and nudity are associated with paganism and be- come regarded as sinful activities by the Roman Church. 1200’s - Thinking it might be a useful skill, European sailors relearn to swim and when they do it, it is in the nude. Women, as the gatekeepers of public morality don’t swim because they have no acceptable swimming garments. -

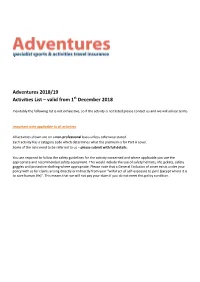

Activities List – Valid from 1St December 2018

Adventures 2018/19 Activities List – valid from 1st December 2018 Inevitably the following list is not exhaustive, so if the activity is not listed please contact us and we will advise terms. Important note applicable to all activities All activities shown are on a non-professional basis unless otherwise stated. Each activity has a category code which determines what the premium is for Part A cover. Some of the risks need to be referred to us – please submit with full details. You are required to follow the safety guidelines for the activity concerned and where applicable you use the appropriate and recommended safety equipment. This would include the use of safety helmets, life jackets, safety goggles and protective clothing where appropriate. Please note that a General Exclusion of cover exists under your policy with us for claims arising directly or indirectly from your "wilful act of self-exposure to peril (except where it is to save human life)". This means that we will not pay your claim if you do not meet this policy condition. Adventures Description category Abseiling 2 Activity Centre Holidays 2 Aerobics 1 Airboarding 5 Alligator Wrestling 6 Amateur Sports (contact e.g. Rugby) 3 Amateur Sports (non-contact e.g. Football, Tennis) 1 American Football 3 Animal Sanctuary/Refuge Work – Domestic 2 Animal Sanctuary/Refuge Work – Wild 3 Archery 1 Assault Course (Must be Professionally Organised) 2 Athletics 1 Badminton 1 Bamboo Rafting 1 Banana Boating 1 Bar Work 1 Base Jumping Not acceptable Baseball 1 Basketball 1 Beach Games 1 Big