Pretty Swimming"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frank C. Graham, 1932 and 1936, Water Polo

OLYMPIAN ORAL HISTORY FRANK C. GRAHAM 1932 & 1936 OLYMPIC GAMES WATER POLO Copyright 1988 LA84 Foundation AN OLYMPIAN'S ORAL HISTORY INTRODUCTION Southern California has a long tradition of excellence in sports and leadership in the Olympic Movement. The Amateur Athletic Foundation is itself the legacy of the 1984 Olympic Games. The Foundation is dedicated to expanding the understanding of sport in our communities. As a part of our effort, we have joined with the Southern California Olympians, an organization of over 1,000 women and men who have participated on Olympic teams, to develop an oral history of these distinguished athletes. Many Olympians who competed in the Games prior to World War II agreed to share their Olympic experiences in their own words. In the pages that follow, you will learn about these athletes, and their experiences in the Games and in life as a result of being a part of the Olympic Family. The Amateur Athletic Foundation, its Board of Directors, and staff welcome you to use this document to enhance your understanding of sport in our community. ANITA L. DE FRANTZ President Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles Member Southern California Olympians i AN OLYMPIAN'S ORAL HISTORY METHODOLOGY Interview subjects include Southern California Olympians who competed prior to World War II. Interviews were conducted between March 1987, and August 1988, and consisted of one to five sessions each. The interviewer conducted the sessions in a conversational style and recorded them on audio cassette, addressing the following -

31 Days of Oscar® 2010 Schedule

31 DAYS OF OSCAR® 2010 SCHEDULE Monday, February 1 6:00 AM Only When I Laugh (’81) (Kevin Bacon, James Coco) 8:15 AM Man of La Mancha (’72) (James Coco, Harry Andrews) 10:30 AM 55 Days at Peking (’63) (Harry Andrews, Flora Robson) 1:30 PM Saratoga Trunk (’45) (Flora Robson, Jerry Austin) 4:00 PM The Adventures of Don Juan (’48) (Jerry Austin, Viveca Lindfors) 6:00 PM The Way We Were (’73) (Viveca Lindfors, Barbra Streisand) 8:00 PM Funny Girl (’68) (Barbra Streisand, Omar Sharif) 11:00 PM Lawrence of Arabia (’62) (Omar Sharif, Peter O’Toole) 3:00 AM Becket (’64) (Peter O’Toole, Martita Hunt) 5:30 AM Great Expectations (’46) (Martita Hunt, John Mills) Tuesday, February 2 7:30 AM Tunes of Glory (’60) (John Mills, John Fraser) 9:30 AM The Dam Busters (’55) (John Fraser, Laurence Naismith) 11:30 AM Mogambo (’53) (Laurence Naismith, Clark Gable) 1:30 PM Test Pilot (’38) (Clark Gable, Mary Howard) 3:30 PM Billy the Kid (’41) (Mary Howard, Henry O’Neill) 5:15 PM Mr. Dodd Takes the Air (’37) (Henry O’Neill, Frank McHugh) 6:45 PM One Way Passage (’32) (Frank McHugh, William Powell) 8:00 PM The Thin Man (’34) (William Powell, Myrna Loy) 10:00 PM The Best Years of Our Lives (’46) (Myrna Loy, Fredric March) 1:00 AM Inherit the Wind (’60) (Fredric March, Noah Beery, Jr.) 3:15 AM Sergeant York (’41) (Noah Beery, Jr., Walter Brennan) 5:30 AM These Three (’36) (Walter Brennan, Marcia Mae Jones) Wednesday, February 3 7:15 AM The Champ (’31) (Marcia Mae Jones, Walter Beery) 8:45 AM Viva Villa! (’34) (Walter Beery, Donald Cook) 10:45 AM The Pubic Enemy -

The University of Chicago Objects of Veneration

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OBJECTS OF VENERATION: MUSIC AND MATERIALITY IN THE COMPOSER-CULTS OF GERMANY AND AUSTRIA, 1870-1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY ABIGAIL FINE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 © Copyright Abigail Fine 2017 All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES.................................................................. v LIST OF FIGURES.......................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES............................................................................................ ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................. x ABSTRACT....................................................................................................... xiii INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER 1: Beethoven’s Death and the Physiognomy of Late Style Introduction..................................................................................................... 41 Part I: Material Reception Beethoven’s (Death) Mask............................................................................. 50 The Cult of the Face........................................................................................ 67 Part II: Musical Reception Musical Physiognomies............................................................................... -

2Friday 1Thursday 3Saturday 4Sunday 5Monday 6Tuesday 7Wednesday 8Thursday 9Friday 10Saturday

JULY 2021 1THURSDAY 2FRIDAY DAYTIME THEME: DAYTIME THEME: TCM BIRTHDAY TRIBUTE: WILLIAM WYLER KEEPING THE KIDS BUSY PRIMETIME THEME: PRIMETIME THEME: SELVIS FRIDAY NIGHT NEO-NOIR Seeing Double 8:00 PM Harper (‘66) 8:00 PM Kissin’ Cousins (‘64) 10:15 PM Point Blank (‘67) 10:00 PM Double Trouble (‘67) 12:00 AM Warning Shot (‘67) 12:00 AM Clambake (‘67) 2:00 AM Live A Little, Love a Little (‘68) 3SATURDAY 4SUNDAY DAYTIME THEME: DAYTIME THEME: SATURDAY MATINEE HAPPY INDEPENDENCE DAY PRIMETIME THEME: PRIMETIME THEME: GABLE GOES WEST HAPPY INDEPENDENCE DAY 8:00 PM The Misfits (‘61) 8:00 PM Yankee Doodle Dandy (‘42) 10:15 PM The Tall Men (‘55) 10:15 PM 1776 (‘72) JULY JailhouseThes Stranger’s Rock(‘57) Return (‘33) S STAR OF THE MONTH: Elvis 5MONDAY 6TUESDAY 7WEDNESDAY P TCM SPOTLIGHT: Star Signs DAYTIME THEME: DAYTIME AND PRIMETIME THEME(S): DAYTIME THEME: MEET CUTES DAYTIME THEME: TY HARDIN TCM PREMIERE PRIMETIME THEME: SOMETHING ON THE SIDE PRIMETIME THEME: DIRECTED BY BRIAN DE PALMA PRIMETIME THEME: THE GREAT AMERICAN MIDDLE TWITTER EVENTS 8:00 PM The Bonfire of the Vanities (‘90) PSTAR SIGNS Small Town Dramas NOT AVAILABLE IN CANADA 10:15 PM Obsession (‘76) Fire Signs 8:00 PM Peyton Place (‘57) 12:00 AM Sisters (‘72) 8:00 PM The Cincinnati Kid (‘65) 10:45 PM Picnic (‘55) 1:45 AM Blow Out (‘81) (Steeve McQueen – Aries) 12:45 AM East of Eden (‘55) 4:00 AM Body Double (‘84) 10:00 PM The Long Long Trailer (‘59) 3:00 AM Kings Row (‘42) (Lucille Ball – Leo) 5:15 AM Our Town (‘40) 12:00 AM The Bad and the Beautiful (‘52) (Kirk Douglas–Sagittarius) -

“Canned History”: American Newsreels and The

“Canned History”: American Newsreels and the Commodification of Reality, 1927-1945 By Joseph E.J. Clark B.A., University of British Columbia, 1999 M.A., University of British Columbia, 2001 M.A., Brown University, 2004 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of American Civilization at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May, 2011 © Copyright 2010, by Joseph E.J. Clark This dissertation by Joseph E.J. Clark is accepted in its present form by the Department of American Civilization as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date:____________ _________________________________ Professor Susan Smulyan, Co-director Date:____________ _________________________________ Professor Philip Rosen, Co-director Recommended to the Graduate Council Date:____________ _________________________________ Professor Lynne Joyrich, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date:____________ _________________________________ Dean Peter Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii Curriculum Vitae Joseph E.J. Clark Date of Birth: July 30, 1975 Place of Birth: Beverley, United Kingdom Education: Ph.D. American Civilization, Brown University, 2011 Master of Arts, American Civilization, Brown University, 2004 Master of Arts, History, University of British Columbia, 2001 Bachelor of Arts, University of British Columbia, 1999 Teaching Experience: Sessional Instructor, Department of Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies, Simon Fraser University, Spring 2010 Sessional Instructor, Department of History, Simon Fraser University, Fall 2008 Sessional Instructor, Department of Theatre, Film, and Creative Writing, University of British Columbia, Spring 2008 Teaching Fellow, Department of American Civilization, Brown University, 2006 Teaching Assistant, Brown University, 2003-2004 Publications: “Double Vision: World War II, Racial Uplift, and the All-American Newsreel’s Pedagogical Address,” in Charles Acland and Haidee Wasson, eds. -

Introduction

NOTES INTRODUCTION 1. Nathanael West, The Day of the Locust (New York: Bantam, 1959), 131. 2. West, Locust, 130. 3. For recent scholarship on fandom, see Henry Jenkins, Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture (New York: Routledge, 1992); John Fiske, Understanding Popular Culture (New York: Routledge, 1995); Jackie Stacey, Star Gazing (New York: Routledge, 1994); Janice Radway, Reading the Romance (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1991); Joshua Gam- son, Claims to Fame: Celebrity in Contemporary America (Berkeley: Univer- sity of California Press, 1994); Georganne Scheiner, “The Deanna Durbin Devotees,” in Generations of Youth, ed. Joe Austin and Michael Nevin Willard (New York: New York University Press, 1998); Lisa Lewis, ed. The Adoring Audience: Fan Culture and Popular Media (New York: Routledge, 1993); Cheryl Harris and Alison Alexander, eds., Theorizing Fandom: Fans, Subculture, Identity (Creekskill, N.J.: Hampton Press, 1998). 4. According to historian Daniel Boorstin, we demand the mass media’s simulated realities because they fulfill our insatiable desire for glamour and excitement. To cultural commentator Richard Schickel, they create an “illusion of intimacy,” a sense of security and connection in a society of strangers. Ian Mitroff and Warren Bennis have gone as far as to claim that Americans are living in a self-induced state of unreality. “We are now so close to creating electronic images of any existing or imaginary person, place, or thing . so that a viewer cannot tell whether ...theimagesare real or not,” they wrote in 1989. At the root of this passion for images, they claim, is a desire for stability and control: “If men cannot control the realities with which they are faced, then they will invent unrealities over which they can maintain control.” In other words, according to these authors, we seek and create aural and visual illusions—television, movies, recorded music, computers—because they compensate for the inadequacies of contemporary society. -

Code De Conduite Pour Le Water Polo

HistoFINA SWIMMING MEDALLISTS AND STATISTICS AT OLYMPIC GAMES Last updated in November, 2016 (After the Rio 2016 Olympic Games) Fédération Internationale de Natation Ch. De Bellevue 24a/24b – 1005 Lausanne – Switzerland TEL: (41-21) 310 47 10 – FAX: (41-21) 312 66 10 – E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.fina.org Copyright FINA, Lausanne 2013 In memory of Jean-Louis Meuret CONTENTS OLYMPIC GAMES Swimming – 1896-2012 Introduction 3 Olympic Games dates, sites, number of victories by National Federations (NF) and on the podiums 4 1896 – 2016 – From Athens to Rio 6 Olympic Gold Medals & Olympic Champions by Country 21 MEN’S EVENTS – Podiums and statistics 22 WOMEN’S EVENTS – Podiums and statistics 82 FINA Members and Country Codes 136 2 Introduction In the following study you will find the statistics of the swimming events at the Olympic Games held since 1896 (under the umbrella of FINA since 1912) as well as the podiums and number of medals obtained by National Federation. You will also find the standings of the first three places in all events for men and women at the Olympic Games followed by several classifications which are listed either by the number of titles or medals by swimmer or National Federation. It should be noted that these standings only have an historical aim but no sport signification because the comparison between the achievements of swimmers of different generations is always unfair for several reasons: 1. The period of time. The Olympic Games were not organised in 1916, 1940 and 1944 2. The evolution of the programme. -

![1944-06-30, [P ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5585/1944-06-30-p-395585.webp)

1944-06-30, [P ]

Friday, .Tune 3*), JQ44 THE TOLEDO UNION JOURNAL Page 5 ‘Dear Marfin Heard on a Hollywood Movie Set HOLLY WOOD — John News and Gossip of Stage and Serei n Conte and Marilyn Maxwell are enacting one of the j. - ■- <fr.:-;-UUZ;.,> . .ll . , ..■■j , f -r .. Lr „ — . .. romantic interludes in the Abbott and Costello starrer, Star I*refers Pie “Lost in a Harem," on &tage Stars Use Own Names 26 at M-G-M. «► As the scene begins, Ar Birthday ‘Cake’ , S mF k v i Conte takes Marilyn's hand HOLLYWOOD — Judy Gar In New Screen Vogue and says; {, .* diettjo, land defied tradition on her HOLLYWOOD (Special)—If a present trend continues in “I love you.” Hofljwood wri’ers may soon stop worrying about what names to “I’m — I’m speechless,” twenty-second birthday. ' ' I ’ says Marilyn. “As we say in At a family dinner tendered give their screen characters. Actors will simply use their own America, 'this is so sud the young star by her mother, names—as more and more of them are now doing. den'.” By TED TAYLOR Mrs. Ethel Gilmore, the familiar Take the instance of Jose Iturbi. He made his screen debat AmAmL W. birthday cake was conspicuous playing himself in "Thousads Cheer.” “After I have regained my throne, will you marry by its absence. Judy’s favorite In 20th Century Fox s Four Jills and a Jeep,” they prac- HOLLYWOOD (FP)—This fs probably the first ease on record dessert is chocolate pie. After tically dropped the traditional me?” Conte asks her. M-G-M Stars Two New “Yes,” repli“s Maralyn, as of a man nominating himself for a movie plot. -

04-15-05 Giving Back

s 2005 Dow Jones & Company. All Rights Reserved. ********* FRIDAY, APRIL 15, 2005 W1 Review / Film Duchovny Does Directing: ‘House of D’ Puts Big Ideas Inside In Cramped, Airless Quarters 7 iii 7 Prison, Death and Jittery Camera Hollywood Report Make Movie FeelConfined; ‘Palindromes’: Dumb Mud 7 7 —By JOE MORGENSTERN— OUSE OF D” is a debut feature written ‘ and directed by David Duchovny, of H“The X-Files” fame. (The title refers to the Women’s House of Detention, a Greenwich Village landmark until it was closed in the 1970s.) In this coming-of-age fable, set in the early ’70s, a prisoner named Lady, who’s doing Homeland insecurity. How U.N. time in solitary confinement, serves as a guard- ian angel for the young hero, Tommy; she dis- politics and sensitivity over penses life lessons from the window of her cell, terrorism interrupted high above the city streets. But then every- ‘The Interpreter.’ W3 one in the film seems to be in solitary, thanks to Mr. Duchovny’s stultify- ing style. If there was a single moment of sponta- neity, it escaped me. Giving Back Ditto for frivolity, though bogus poetry abounds. It’s always dangerous to make assumptions about how and why bad movies come into being. (Good ones can be a mys- David Duchovny tery too.) Still, the evi- Growing Celebrity dence on screen points to an overabundance of literary ambition and an underabundance of self-irony, or maybe just a Striped grass. Shark tanks. A new crop of landscape lack of common sense about how many earnest themes and meaningful moments can be stuffed designers is using edgy projects to attract fame and high fees. -

In 1925, Eight Actors Were Dedicated to a Dream. Expatriated from Their Broadway Haunts by Constant Film Commitments, They Wante

In 1925, eight actors were dedicated to a dream. Expatriated from their Broadway haunts by constant film commitments, they wanted to form a club here in Hollywood; a private place of rendezvous, where they could fraternize at any time. Their first organizational powwow was held at the home of Robert Edeson on April 19th. ”This shall be a theatrical club of love, loy- alty, and laughter!” finalized Edeson. Then, proposing a toast, he declared, “To the Masquers! We Laugh to Win!” Table of Contents Masquers Creed and Oath Our Mission Statement Fast Facts About Our History and Culture Our Presidents Throughout History The Masquers “Who’s Who” 1925: The Year Of Our Birth Contact Details T he Masquers Creed T he Masquers Oath I swear by Thespis; by WELCOME! THRICE WELCOME, ALL- Dionysus and the triumph of life over death; Behind these curtains, tightly drawn, By Aeschylus and the Trilogy of the Drama; Are Brother Masquers, tried and true, By the poetic power of Sophocles; by the romance of Who have labored diligently, to bring to you Euripedes; A Night of Mirth-and Mirth ‘twill be, By all the Gods and Goddesses of the Theatre, that I will But, mark you well, although no text we preach, keep this oath and stipulation: A little lesson, well defined, respectfully, we’d teach. The lesson is this: Throughout this Life, To reckon those who taught me my art equally dear to me as No matter what befall- my parents; to share with them my substance and to comfort The best thing in this troubled world them in adversity. -

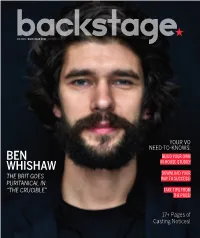

Ben Whishaw Photographed by Matt Doyle at the Walter Kerr Theatre in NYC on Feb

03.17.16 • BACKSTAGE.COM YOUR VO NEED-TO-KNOWS: BEN BUILD YOUR OWN WHISHAW IN-HOUSE STUDIO! DOWNLOAD YOUR THE BRIT GOES WAY TO SUCCESS! PURITANICAL IN “THE CRUCIBLE” TAKE TIPS FROM THE PROS! 17+ Pages of Casting Notices! NEW YORK STELLAADLER.COM 212-689-0087 31 W 27TH ST, FL 3 NEW YORK, NY 10001 [email protected] THE PLACE WHERE RIGOROUS ACTOR TRAINING AND SOCIAL JUSTICE MEET. SUMMER APPLICATION DEADLINE EXTENDED: APRIL 1, 2016 TEEN SUMMER CONSERVATORY 5 Weeks, July 11th - August 12th, 2016 Professional actor training intensive for the serious young actor ages 14-17 taught by our world-class faculty! SUMMER CONSERVATORY 10 Weeks, June 6 - August 12, 2016 The Nation’s Most Popular Summer Training Program for the Dedicated Actor. SUMMER INTENSIVES 5-Week Advanced Level Training Courses Shakespeare Intensive Chekhov Intensive Physical Theatre Intensive Musical Theatre Intensive Actor Warrior Intensive Film & Television Acting Intensive The Stella Adler Studio of Acting/Art of Acting Studio is a 501(c)3 not-for-prot organization and is accredited with the National Association of Schools of Theatre LOS ANGELES ARTOFACTINGSTUDIO.COM 323-601-5310 1017 N ORANGE DR LOS ANGELES, CA 90038 [email protected] by: AK47 Division CONTENTS vol.57,no.11|03.17.16 NEWS 6 Ourrecapofthe37thannualYoung Artist Awardswinners 7 Thisweek’sroundupofwho’scasting whatstarringwhom 8 7 brilliantactorstowatchonNetflix ADVICE 11 NOTEFROMTHECD Themonsterwithin 11 #IGOTCAST EbonyObsidian 12 SECRET AGENTMAN Redlight/greenlight 13 #IGOTCAST KahliaDavis -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 75-3121

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation.