Breast ^Feeding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Power and Resistance in Biomedical and Midwifery Models of Birth

“BECAUSE IT IS MY BODY, AND I OWN IT, AND I AM IN CHARGE”: POWER AND RESISTANCE IN BIOMEDICAL AND MIDWIFERY MODELS OF BIRTH By KATHRYN WORMAN ROSS Bachelor of Science in Sociology and Psychology Jacksonville State University Jacksonville, Alabama 2004 Master of Arts in Sociology Middle Tennessee State University Murfreesboro, Tennessee 2007 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 2013 “BECAUSE IT IS MY BODY, AND I OWN IT, AND I AM IN CHARGE”: POWER AND RESISTANCE IN BIOMEDICAL AND MIDWIFERY MODELS OF BIRTH Dissertation Approved: Dr. Stephen M. Perkins Dissertation Adviser Dr. Tamara L. Mix Dissertation Adviser Dr. J. David Knottnerus Dr. Virginia A. Worley ii Name: KATHRYN WORMAN ROSS Date of Degree: MAY, 2013 Title of Study: “BECAUSE IT IS MY BODY, AND I OWN IT, AND I AM IN CHARGE”: POWER AND RESISTANCE IN BIOMEDICAL AND MIDWIFERY MODELS OF BIRTH Major Field: SOCIOLOGY Abstract: I utilize participant observation, autoethnography and in-depth interviews with women who have given birth at home and homebirth midwives in Oklahoma to understand perceptions and responses to society’s hegemonic birth system, its power, ideology, and practices. Employing Foucauldian, Foucauldian feminist, and Social Constructivist frameworks, I illuminate issues of reality construction, knowledge, and power related to the homebirth experience. Participants expressed distinctions between biomedical and midwifery models. They described complex processes whereby women’s bodies are transformed into docile bodies through disciplinary technologies, including control of ideology and panopticonic domination of time, space, and movements of the body. -

Reversal Theory and Mother-Child Compatibility Reversal Theory and Mother-Child Compatibility

Reversal Theory and Mother-Child Compatibility Reversal Theory and Mother-Child Compatibility bY Pauline Roberta O'Connor B.A. (Vic.), B.Sc. Hons (Vic.) in the Department of Psychology Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania January, 1992 I certify that this thesis contains no material that has been accepted for the award of any other higher degree or graduate diploma in any university, and that to the best of my knowledge and belief the thesis contains no copy or paraphrase of material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference is made in the text of the thesis. The advice I'd give is don't feel obligated to follow through if there is any trait in that kid's personality that seems totally incongruent with your own. Don't feel weird about taking them back and trying somebody else.... Adoptive parent in Grotevant, McRoy and Jenkins (1988) (iv) Abstract Apter (1982, 1989) and Apter and Smith (1979) reinterpret tnany problems of the family in terms of the theory of psychological reversals (Smith & Apter, 1975). Apter and Smith hypothesise that many family problems arise out of an incompatibility between family members due to telic/paratelic mode- opposition or conformist/negativist mode-opposition (i.e. two individuals occupying the opposite mode at the same time). One may adduce as further evidence for this suggestion a body of literature in Social Psychology suggesting that we like those who are similar to ourselves and dislike those who are dissimilar to ourselves. -

Breastfeeding and Maternal Touch After Childhood Sexual Assault

Breastfeeding and Maternal Touch after Childhood Sexual Assault Janice Yvonne Coles Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2006 Centre for Health and Society University of Melbourne Abstract Introduction: The study is a qualitative exploration of breastfeeding and maternal touch with new mothers who are survivors of childhood sexual assault (CSA) by a family member. Objectives: The objective of this study is to explore the experience of breastfeeding in mothers with a past history of CSA perpetrated by a family member. Methods: Using an interpretive framework, eleven women were interviewed with an in-depth semi-structured method and the transcripts coded and analysed by themes. All participants were new mothers who volunteered in response to a community based advertisement. Each woman self- identified as being sexually abused as a child by a family member. Results: Significant themes that emerged about breastfeeding were the importance of breastfeeding to the maternal-infant relationship and infant development. Other more challenging themes included detachment and dissociation, exposure and control, lack of pleasure, and splitting of the roles of the breasts into maternal or sexual objects. During the course of the study maternal-infant touch was raised as an important theme associated with body boundaries between the mother and her child and related to the mother’s past CSA experience. Baths and nappy changes were two areas in which some mothers encountered difficulties associated directly with their CSA. Some participants encountered difficulties associated with their healthcare. These were largely associated with the participants’ lack of control in the professional encounter and intimate examinations. -

Iiusicweek for Everyone in the Business of Music 16 SEPTEMBER

iiusicweek For Everyone in the Business of Music 16 SEPTEMBER 1995 £3.10 Simply Red the new single 'Fairground' Release date 18th September Formats: 2CDs, Cassette CD1 includes live tracks CD2 includes remixes w thusfcwe For Everyone in the Business of Music 16 SEPTEMBER 1995 THIS WEEK Black retumsto EMI as MD 4 Help wi He says his former colleague was the Warners and am now looking At 33, Black joins a growing list of agamsttjme Clive Black has finally been installed only"When candidate Manchester for his oldjob. United were -------theEMI. challenges Besides, ofJF- my put new r youthfu!industry, managingalongside directors MCA's in Nickthe lOBlur ingas managing weeks of spéculation. director of EMI UK, end- ers,champions, but you they don't tried change to change a winning play- Cecillon adds that I mldn't refuse." Phillips,RCA's Hugh 32, Goldsmith,_35,Epic's Rob Stringer, BMG misic _33, iWadsworth the company he left at the beginning of between' " ' us ays. "The ' ' îtry' Works inhis A&R new will job. be an"I aci division président Jeremy Marsh, 35, 12PRS:agm department,last year following most recently10 years inas itshead A&R of teamBlack again. wf ■ork alongside the tv UKandthekeytothfParlophone to be the signais s been WEA A&R Ton; il b managingand Roger directors Lewis, A&R drivenguy - probablyand becaus tl replacesdirector Jeanfor theFran | areporting daily basis. directly Cecillon to stresses him,"usiness he says.- tlu for Aftera manager two years at Intersong he moved Musicon to h I vacated the positioi will be given a free rein, "My mesf raftBlack of acts was to responsible the label in for his bringing last spell a movingWEA, to EMIwhose in 1984.managing di danceat EMI actUK, Markand at MorrisonWEA, he signedand teennew Moira BeUas says she wishes Black i group Optimystic. -

New Bus Bias Tests Hartford, May 23 M— by Alleghany Corp

.,='---,l*.,. ' ... --- - - ' • . = • » __ _ .. » I ' . ' - ./ ^ : i , ■• Artngt Daily Net Press Run The Weather . t For the Week Ended roreeeit of O. S. Wenthet B nw a i. > Mejr e,. 1S61 Fair, cooler tonight, chenoS «C' 13,326 troet In normally eoMer sMMW Member of the Audit l«W IS to 4it~Falr, Whdnniilsy,; Burenn of Olrcoletlon High In 60e. Manche»ter—rA City of Village Charm VOL. LXXX, NO. 198 (SIXTEEN PAGES) MANCHESTER, CONN., TUESDAY; MAY 23, 1961 (Claeairied Adrertlaing on Page 14) PRICE FIVE CENTS !% . ’ a Congress^ Castro Riled Stale News Alleghany’s Roundup Empire to Dispute Perils X Dempsey Vetoes MureMsons Extending Hour$« Baltimore, May 23 (/P)— Captives Deal The epic "Battle of Million- On Liquor Sales aires" for control of the $6.7 billion financial empire ruled New Bus Bias Tests Hartford, May 23 m— by Alleghany Corp. ended to- Washington, May 23 (/P)— American people to make a etate- of policy on the offer. Gov. John N. Dempsey vetoed day with a victory for the in- Crackling charges and de- asked I a bill that would extend the surgent Murchison brothers. mands threatened the trac- soon "what the posltlom of our hours during which liquor can Never before had a proxy fight tors-for-prisoners trade today government is." be sold legally on Sunday on been waged for such stakes. Nazis Ride from two sides— the U.S. Morse called it "a dangerous All that remained was • formal thing to countenance" voluntary the irroutvds that to do so announcement of the margin in Congress and Fidel Castro. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

Julian Cope E I Teardrop Explodes

JULIAN COPE E I TEARDROP EXPLODES Letture consigliate: Simon Reynolds: Post-punk, ISBN Julian Cope: Head-on, Lian Julian Cope: Repossessed, Lian Dischi consigliati: Teardrop explodes: Kilimanjaro Julian Cope: Fried Julian Cope: Jehovakill Scordatevi i Duran Duran o gli Spandau Ballett, lasciate perdere gli U2, snobbate gli Echo and the bunnymen e gli Psychedelic Furs: se nella seconda metà del 1980, dopo il suicidio di Ian Curtis dei Joy Division, aveste chiesto a qualsiasi giornalista musicale quale sarebbe stata la “next big thing” della musica inglese, la risposta sarebbe stata quasi sicuramente i Teardrop explodes. Nati l’anno precedente grazie alla determinazione del giovane Julian Cope, i Teardrop explodes (l’unico gruppo con un participio passato nel nome – come affermato da loro stessi) si fecero ben presto notare per alcuni singoli ottimamente recensiti dalla critica specializzata. Sleeping gas , Treason e When I Dream furono anche grandi e inaspettati successi commerciali, portando alla ribalta nazionale la piccola ma attiva comunità punk di Liverpool che aveva dato vita ad un’interessante scena New-pop. Tra i vari gruppi che la componevano cito gli Echo and the bunnymen, i Big in Japan e, naturalmente, i Teardrop explodes di Julian Cope, la cui attività artistica sarà al centro di questa prima parte dell’articolo. Nato nel 1957 in Galles, Julian passò la sua adolescenza a Tamworth nello Staffordshire; nonostante fosse cresciuto lontano dai centri culturali inglesi, Cope possedeva un’ottima conoscenza della musica rock, peculiarità decisiva per la sua vita - e per l’articolo che state leggendo. Egli infatti riversò nelle canzoni dei Teardrop explodes - e dei suoi dischi solisti - tutta la passione per il pop degli anni Sessanta, arricchendolo con una psichedelia barrettiana e sprazzi di follia sperimentale krautrock, rileggendo il tutto alla luce della nuova sensibilità New wave. -

BB-1995-07-22.Pdf

$5.50 (U.S.), $6.50 (CAN.), £4.50 (U.K.) IN MUSIC NEWS *BXNCCVR ******** 3 -DIGIT 908 MCA Primes tGEE4EM740M099074$ 002 0663 000 BI MAR 2396 1 03 MONTY GREENLY Fans For 3740 ELM AVE APT A LONG BEACH, CA 90807 -3402 Buffett's `Barometer Soup' SEE PAGE 10 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT JULY 22, 1995 ADVERTISEMENTS TICKETMASTER RIVALS SEEK NEW BIZ Sony's `Spirit BY ERIC BOEHLERT competition. That's because a handful More than 20 years ago, while sitting of challengers covering a patchwork of in the stands at an Arizona State Uni- Of '73' Rocks NEW YORK -Ever since it pur- regions are bidding and occasionally versity football game, computer pro- chased assets from once -mighty com- winning contracts to provide the same grammer Dorothy McLaughlin joined petitor Ticketron in 1991, critics have types of services that Ticketmaster of- her sister and brother-in -law, Margie For Pro -Choice charged that Ticketmaster faces no ri- fers: box -office support, phone rooms, and Bill Bliss, in a brain teaser: Why val and has cornered itself a lucrative a network of satellite outlets, and pro- couldn't tickets be sold electronically BY CHRIS MORRIS market. motional dollars. from various remote outlets, allowing congratulates The accusation, with which the Jus- Despite Ticketmaster selling 55 mil- all customers the same seat selection? LOS ANGELES -Sony 550 Music will mate activist zeal with a sense of nostalgic fun on Aug. 8, when it Carl P. Mayfield, Tele- charge Systemsó SONY Loscalzo & PROTIX. Dil1an1's lion tickets last year and its regional the staffs of competitors moving just a fraction of tice Department's recent investigation that number, the seemingly mis- At the time, companies bicycled did not concur, stems not only from the matched duels continue to unfold. -

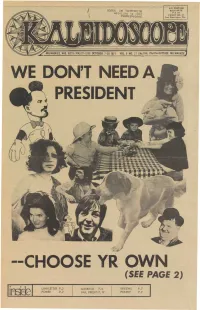

I / EI I (SEE PAGE 2)

jiiPj!^.j|^ Mut^Po^r*idE S0S2S IM *a9"Jm^MxT^ BULK RATE PAID PERMIT NO. 33 suourpsuopjof) Port Washington, Wis. WE DON'T NEED A PRESIDENT I -CHOOSE YR OWN I I / EI i (SEE PAGE 2) LINKLETTER P.3 GARBAGE P. 6 REV.EWS P. 7 POWER -P. 2 FAB. FREEKS P. 12 POETRY P. 9 t$BLi$f agatf^/ This Is Issue No. 104 and fs alsojthe anniversary, of our Fourth Vear et publishing. It's still hard to baftevel Itiere's been a lot of hype and a lot of guff lately about. the "righteous** concept of FREE newspapers. First of sll, " ICALEIDOSGOPE sttU costs a quarter. and If by some miracle we could affords print,an average of 10,000 copies an issuefce hype!) without charging for It we would still have second thoughts. <- \ , Last year, (no "hype * y&n can. inspect our books) almost .8,000 doHars(not counting the 20 per. cent rip-off rate that we have to deal with) was earned by freaks lr» the com munity. That's a lot of money that would be lost to our brothers and sisters if we gave K-scope away tree* "*• We can't afford it, and neither can the community. Others can hype what they* want^, 1 guess-If you can't sell it you HAVE to give it away. Besides, the amount of Utter 04i. Bradv St. is, quite sufficient. Enough $sid* "the Glebbies are doing a terrific job, in case you've been oat of touch, with both their recycling truck and the FREE MEAL every Thursday night -at 6pm at the Gommun- ; ity Center,911 E, Ogden. -

Behavioral Science, Fifth Edition

BRS-Fadem_FM_i-xvi.qxd 8/21/08 11:34 AM Page i Behavioral Science BRS-Fadem_FM_i-xvi.qxd 8/21/08 11:34 AM Page ii BRS-Fadem_FM_i-xvi.qxd 8/21/08 11:34 AM Page iii Behavioral Science Barbara Fadem, Ph.D. Professor Department of Psychiatry University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey New Jersey Medical School Newark, New Jersey BRS-Fadem_FM_i-xvi.qxd 8/21/08 11:34 AM Page iv Acquisitions Editor: Crystal Taylor Managing Editor: Stacey L. Sebring Marketing Manager: Emilie Moyer Production Editor: Paula C. Williams Designer: Holly Reid McLaughlin Compositor: International Typesetting and Composition Fifth Edition Copyright © 2009, 2005 by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a Wolters Kluwer business. 351 West Camden Street 530 Walnut Street Baltimore, MD 21201 Philadelphia, PA 19106 Printed in United States of America All rights reserved. This book is protected by copyright. No part of this book may be reproduced or trans- mitted in any form or by any means, including as photocopies or scanned-in or other electronic copies, or utilized by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the copyright owner, except for brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Materials appearing in this book prepared by individuals as part of their official duties as U.S. government employees are not covered by the above-mentioned copyright. To request permission, please contact Lippincott Williams & Wilkins at 530 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19106, via email at [email protected], or via website at lww.com (products and services). 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fadem, Barbara. -

Cronologia Dei Principali Album E Delle Migliori

1 Cronologia dei principali album 1963 The Beatles Please, Please Me mar With the Beatles nov 1964 The Rolling Stones Rolling Stones apr 12X5 nov The Beatles A Hard Day's Night lug Beatles for Sale dic The Yardbirds Five Live Yardbirds dic 1965 The Kinks Kinda Kinks mar The Rolling Stones Now apr Out of Our Heads lug Donovan Whats Bin Did and What’s Bin Hid mag Fairytale ott Moody Blues The Magnificent Moodies lug The Beatles Help ago Rubber Soul dic The Kinks Face to Face ott The Who My Generation dic 1966 The Rolling Stones Aftermath apr John Mayall, Eric Clapton Mayall’s Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton lug The Yardbirds Roger the Engineer lug The Beatles Revolver ago Donovan Sunshine Superman set The Who A Quick One dic Cream Fresh Cream dic 1967 Donovan Mellow Yellow gen 2 The Rolling Stones Between the Buttons gen Their Satanic Majesties Request dic John Mayall Hard Road feb Crusade set Small Faces Small Faces giu The Beatles Sgt Pepper giu Magical Mystery Tour dic The Bee Gees The Bee Gees 1st lug The Yardbirds Little Games lug Pink Floyd The Piper at the Gate of Down ago Animals Winds of Change set Ten Years After Ten Years After ott The Who The Who Sell Out nov Cream Disraeli Gears nov Moody Blues Days of Future Passed nov Nice The Thought of Emerlist Davjack dic Traffic Mr Fantasy dic The Kinks Something Else m s Brian Auger Open m s 1968 The Bee Gees Horizontal gen Procol Harum Procol Harum gen Shine on Brightly dic John Martyn London Conversation feb Small Faces Ogden’s Nut Gome Flake mag Pentangle Pentangle giu Sweet Child -

Mein Krautrocksampler

Krautrocksampler Interviews, Artikel und anderes extrahiert aus dem Internet und aufbereitet von Heinrich Unkenfuß Nur zum internen Gebrauch und zu wissenschaftlichen und Unterrichtszwecken. Hamburg, 13. 11. 2010 Inhaltsverzeichnis Ein Augen- und Ohrenflug zum letzten Himmel - Die Deutsche Rockszene um 1969 (von Marco Neumaier) 4 The German Invasion (by Mark Jenkins) 7 Krautrock (by Chris Parkin) 10 Rock In Deutschland - Gerhard Augustin Interview 12 An Interview With Julian Cope 17 Krautrock: The Music That Never Was 22 German Rock (SPIEGEL 1970) 25 Popmusik: Sp¨ates Wirtschaftswunder (SPIEGEL 1974) 27 Neger vom Dienst (SPIEGEL 1975) 29 Trance-Musik: Schamanen am Synthesizer (SPIEGEL 1975) 31 Zirpt lustig (SPIEGEL 1970) 34 Prinzip der Freude (SPIEGEL 1973) 36 The Mythos of Rolf-Ulrich Kaiser (1943-??) 38 Exhibitionisten an die Front (SPIEGEL 1969) 42 Communing With Chaos (by Edwin Pouncey) 44 Amon Du¨ul¨ II - Yeti Talks to Yogi 50 We Can Be Heroes (Amon Du¨ul¨ II) 57 Interview with John Weinzierl 60 Dave Anderson - The Bass-Odyssey Files 69 1 Kraut-Rock (Interview mit Chris Karrer) 74 Interview mit Tangerine Dream (1975) 77 Interview with Klaus Schulze 79 “I try to bring order into the chaos.” Klaus D. Mueller Interview 91 Die wahre Geschichte des Krautrock 96 Faust: Clear 102 The Sound of the Eighties 104 Faust and Foremost: Interview with Uwe Nettelbeck 107 Having a Smashing Time 110 Interview with Jochen Irmler 115 After The Deluge - Interview with Jean-Herv´eP´eron 117 Faust: Kings of the Stone Age 126 Faust - 30 Jahre Musik zwischen Bohrmaschine und Orgel 134 Hans Joachim Irmler: ‘Wir wollten die Hippies mal richtig erschrecken“’ 140 ” Can: They Have Ways of Making You Listen 145 An Interview With Holger Czukay (by Richie Unterberger) 151 An Interview With Holger Czukay (by Jason Gross) 155 D.A.M.O.