Chandore’ in India’S Western Ghats Ancient Asia – Using Ethno-Historic Study and Sculptural Details As Complementary Factors to Spatial Techniques

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

4.31 History (Paper-I)

Enclosure to Item No. 4.31 A.C. 25/05/2011 UNIVERSITY OF MUMBAI Syllabus for the F.Y.B.A. Program : B.A. Course : History (Paper-I) (History of Modern Maharashtra 1848-1960 AD) (Credit Based Semester and Grading System with effect from the academic year 2011‐2012) 1. Syllabus as per Credit Based Semester and Grading System. i. Name of the Programme - B.A. ii. Course Code ‐ iii. Course Title - History (Paper-I) (History of Modern Maharashtra 1848-1960 AD) iv. Semester wise Course Contents - As per Syllabus v. References and additional references ‐ Submitted already vi. Credit structure - 3 Semester-I & 3 Semester-II vii. No. of lectures per Unit - 11,11,11 & 12 = 45 viii. No. of lectures per week / semester - 45 lectures per semester 2. Scheme of Examination ‐ 4 questions of 15 marks each internal & semester end. 3. Special notes, if any ‐ As per University Norms 4. Eligibility, if any ‐ As per University Norms 5. Free Structure ‐ As per University Norms 6. Special Ordinances / Resolutions, if any ‐ History of Modern Maharashtra (1848-1960) Semester End Examination 60 marks and Internal assessment 40 marks =100 marks per semester The Course should be completed / Covered/Taught in 45 (forty-five) Lectures (45) learning hours for Students) per Semester. In addition to this the student required to spend same number of hours (45) on self study in Library and / or institution or at home, on case study, writing journal, assignment, project etc to complete the course. The total credit value of this course is (03) three credits 45 teaching hours plus 45 hours self study of the student). -

Ancient Indian History, Culture & Archeaology

AC 7‐6‐13 Item no. 4.2 UNIVERSITY OF MUMBAI Revised Syllabus for the M.A. Program: M.A. Course: (Ancient Indian History, Culture & Archeaology) Semester I to IV (Credit Based Semester and Grading System with effect from the academic year 2013–2014) 1 M.A. (Ancient Indian History,Culture & Archeaology) Syllabus as per Credit Based and Grading System Ancient Indian History,Culture And Archaeology 1. Syllabus as per Credit Based and Grading System. i. Name of the Program: M.A. (96 Credits) ii. Course Code: ‐ PAAIC iii. Course Title: Ancient Indian History, Culture & Archaeology iv. Semester wise Course Contents: ‐ Listed below v. References and additional references: ‐Listed below v i Sem III .C I Religion and Philosophy I CII Language and Literature I O I Indian Aesthetics C rOII Economic History eOIII History and Culture of SouthEast d Asia iOIV History and Culture of East Asia Sem IV t C I Religion and Philosophy II CII Language and Literature II sO I Cultural Tourism tOII Cultural History and Archaeology of Maharashtra OIII Social life in Ancient India2 OIV Science and Technology in Ancient India ructure: I Sem / II Sem - 24 / 24 Minimum Qualification for Teachers: Course Code Name of the Course Minimum Qualification of Teachers PAAIC Religion and Philosophy M.A. in Ancient Indian History, Culture & Archaeology, History, Sanskrit, PAAIC Language and Literature M.A. in Ancient Indian History, Culture & Archaeology, History, Sanskrit, Pali, Prakrit PAAIC Indian Aesthetics M.A. in Ancient Indian History, Culture & Archaeology, History, Sanskrit PAAIC Economic History M.A. in Ancient Indian History, Culture & Archaeology, History, PAAIC History and Culture of South M.A. -

A CASE STUDY of LEARN, DHARAVI Dissertation Submitted

ROLE OF SOCIAL MOVEMENTS IN ORGANISING THE UNORGANISED SECTOR WORKERS: A CASE STUDY OF LEARN, DHARAVI Dissertation Submitted for the Partial Fulfilment of the M. A. in Globalisation and Labour for the Academic Year 2008-2010 By: Tinu K. Mathew 2008GL023 M. A. in Globalisation and Labour Tata Institute of Social Sciences Mumbai – 400088 Research Guide: Dr. Ezechiel Toppo Associate Professor and Chairperson Centre for Labour Studies School of Management and Labour Studies Tata Institute of Social Sciences Mumbai – 400088 March 2010 ROLE OF SOCIAL MOVEMENTS IN ORGANISING THE UNORGANISED SECTOR WORKERS: A CASE STUDY OF LEARN, DHARAVI Submitted By: Tinu K. Mathew 2008GL023 M. A. in Globalisation and Labour Tata Institute of Social Sciences Mumbai – 400088 March 2010 ii Tata Institute of Social Sciences, VN Purav Marg, Deonar, Mumbai – 400 088 Tel: +91-22-25525000 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the research report entitled ‘ROLE OF SOCIAL MOVEMENTS IN ORGANISING THE UNORGANISED SECTOR WORKERS: A CASE STUDY OF LEARN, DHARAVI’ is the record of the original work done by Tinu K. Mathew under my guidance. This work is original and has not been submitted in part or full to any other university or institute for the award of any Degree or Diploma. I certify that the above declaration is true to the best of my knowledge and belief. Dr. Ezechiel Toppo Associate Professor and Chairperson Centre for Labour Studies School of Management and Labour Studies Tata Institute of Social Sciences Mumbai – 400088 Place: Mumbai Date : ..................... iii DECLARATION The research report entitled ‘ROLE OF SOCIAL MOVEMENTS IN ORGANISING THE UNORGANISED SECTOR WORKERS: A CASE STUDY OF LEARN, DHARAVI’ has been prepared entirely by me under the guidance of Dr. -

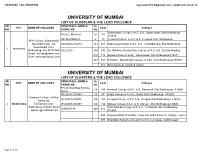

Revised List of Lead / Cluster Colleges for TY Bcom

26543035 / 36, 26530283 [email protected], [email protected] UNIVERSITY OF MUMBAI LIST OF CLUSTERS & THE LEAD COLLEGES SR. PRINCIPALS NAME & Sr. DIST. NAME OF COLLEGES Code Colleges NO. PHONE NO. No. Sawantwadi College of A.C. & S., Sawantwadi. Dist.Sindhudurg - Prin D L Bharmal 67 187 416510 (M) 9422964019 2 13 Vengurla College of A.C. & S. Vengurla, Dist. Sindhudurg. SPK College, Sawantwadi, Near Moti Talav, Tal. (O) 02363 272017 148 543 Dodamarg College of A.C. & S., Tal Dodamarg, Dist.Sindhudurg Sawantwadi, Dist-: 1 Sindhudurg Sindhudurg- 416 510 E-Mail (D) 272017 168 592 Sai Shikshan Santha Oras College of A.C. & S., Dist.Sindhudurg Id [email protected] 210 712 Banda College of A.&C., Sawantwadi, Dist.Sindhudurg-416511 Web:- www.spkcollege.com 237 834 B.S.Naik - Sawantwadi College of A.&C., Dist.Sindhudurg-416510 955 Shivraj College of Arts & Comm. UNIVERSITY OF MUMBAI LIST OF CLUSTERS & THE LEAD COLLEGES SR. PRINCIPALS NAME & Sr. DIST. NAME OF COLLEGES Code Colleges NO. PHONE NO. No. Prin.Dr.Sambhaji Krishna 85 244 Kankavli College of A.C. & S., Kankavali, Dist.Sindhudurg - 416602 Shinde (O) 02367-230365 30 97 Kudal College of A. & C., Kudal, Dist. Sindhudurg - 416520 Kankavli College, At Post (F) 02367-232053 64 182 Devgad College of A.C. & S., Deogad, Dist.Sindhudurg - 416613 Kankavali, 2 Sindhudurg Tal.Kankavli,Dist.: (R) 02367-232087 66 186 Malvan College of A.C. & S., Malvan , Dist.Sindhudurg-416606 Sindhudurg- 416602. Email Katta-Malvan College of A. & C., Tal.Malvan, Dist.Sindhudurg- 9405928799 246 882 : [email protected] 416604 954 Dnyanvardhini Charitable Trusts Arts and Commerce College, Talere 399 Anandibai Raorane Arts and Commerce College, Vaibhavwadi Page 1 of 23 26543035 / 36, 26530283 [email protected], [email protected] UNIVERSITY OF MUMBAI LIST OF CLUSTERS & THE LEAD COLLEGES SR. -

[email protected]

CURRICULUM VITAE Dr. MANISHA RAO Assistant Professor Department of Sociology University of Mumbai Vidyanagari Campus, Kalina Santacruz (E), Mumbai-98 Phone: 9920369059 Email: [email protected] [email protected] Education Ph. D. October 2006. Title of Thesis: „The Sociological Analysis of an Environmental Movement: The case of Appiko, Uttara Kannada District‟. Supervisor: Prof. D.N. Dhanagare. Department of Sociology, University of Pune, Pune. M.Phil. February 1994. Title of Dissertation: „Underdevelopment Theories: A Gender Sensitive Critique‟. Supervisor: Prof. V. Xaxa, Dept. of Sociology, Delhi School of Economics, University of Delhi, Delhi. M.A. 1992. 1st Class with Distinction, from Dept. of Sociology, University of Pune, Pune. B.A.(Hons.) 1990. Political Science, from Lady Shri Ram College for Women, University of Delhi, New Delhi. Senior Secondary School Certificate. 1987. Humanities, 1st Division, from The Holy Child Auxilium School, New Delhi. Awards Awarded Major Research Project of Indian Council of Social Science Research, New Delhi. Grant amount INR Eight Lacs, 2017-2019. Awarded U.G.C.- J.R.F. in January 1999. Awarded U, G, C.- N.E.T. in January 1996. Awarded Daulat R. Desai Prize for Leadership; Principals‟ Prize for Service to the College. L.S.R. New Delhi.1990. 1 Distinctions Member, Editorial Advisory Committee - Sociological Bulletin, Official Journal of the Indian Sociological Society, March 2018-February 2020. Member, Editorial Advisory Committee – Explorations E-Journal of the Indian Sociological Society, April 2020- March 2022. Member, Editorial Advisory Board - „Quest in Education‟, Gandhi Shiksha Bhavan, Mumbai, since June 2014. President, Students Council, (1989-‟90) Lady Shri Ram College for Women, New Delhi. -

Mumbai Local Sightseeing Tours

Mumbai Local Sightseeing Tours HALF DAY MUMBAI CITY TOUR Visit Gateway of India, Mumbai's principle landmark. This arch of yellow basalt was erected on the waterfront in 1924 to commemorate King George V's visit to Mumbai in 1911. Drive pass the Secretariat of Maharashtra Government and along the Marine Drive which is fondly known as the 'Queen's Necklace'. Visit Jain temple and Hanging Gardens, which offers a splendid view of the city, Chowpatty, Kamala Nehru Park and also visit Mani Bhavan, where Mahatma Gandhi stayed during his visits to Mumbai. Drive pass Haji Ali Mosque, a shrine in honor of a Muslim Saint on an island 500 m. out at sea and linked by a causeway to the mainland. Stop at the 'Dhobi Ghat' where Mumbai's 'dirties' are scrubbed, bashed, dyed and hung out to dry. Watch the local train passing close by on which the city commuters 'hang out like laundry' ‐ a nice photography stop. Continue to the colorful Crawford market and to the Flora fountain in the large bustling square, in the heart of the city. Optional visit to Prince of Wales museum (closed on Mondays). TOUR COST : INR 1575 Per Person The tour cost includes : • Tour in Ac Medium Car • Services of a local English‐speaking Guide during the tour • Government service tax The tour cost does not include: • Entry fees at any of the monuments listed in the tour. The same would be on direct payment basis. • Any expenses of personal nature Note: The above tour is based on minimum 2 persons traveling together in a car. -

Dr. Bharat Bhushan

Dr. Bharat Bhushan Full Name : Dr. Bharat Bhushan Designation : Professor, Environmental Planning Dean (Academic) and Secretary, YASHADA Academic Qualifications :PhD (Zoology), 1994, University of Mumbai, MSc (Zoology), 1985, University of Mumbai, ISO 9001:2000, Certified Lead Auditor - Quality Management, ISO 14000:2004, Certified Lead Auditor - Environment Management Contact Nos. : 020-25608155 (Off.), 9823338227 (Mob.) E-mail ID : [email protected] Date of Joining : 01/03/96 Professional Experience / Previous Postings : Dean (Academic), YASHADA (June 2008 onwards) 2004-2008: Deputy Director General (Planning), Planning Division, YASHADA and Professor, Environmental Planning 1996-2004: Associate Professor, Environmental Planning and Director, Centre for Environment and Development, Yashwantrao Chavan Academy of Development Administration, Government of Maharashtra, Pune, India 1995-1996: Research Associate, Associates in Biodiversity and Conservation, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, Gainesville, USA 1995: Senior Project Officer, Biodiversity Conservation Programme,India 1994-1995: Research Associate, Harini Nature Conservation Foundation, Mumbai (Bombay), India 1993-1994: Programme Officer, South Asia, Asian Wetlands Bureau, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 1992-1993: Pre-doctoral Research Associate, S. Dillon Ripley Bird Laboratory, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D. C., United States of America 1982-1992: Scientist + Conservation Officer, Bombay Natural History -

Maharashtra Census 2011 Pdf in Marathi

Maharashtra census 2011 pdf in marathi Continue The state of Maharashtra is located in the western part of India. Maha means large and rastra means state in Hindi and covers an area of 307,713 square kilometers (118,809 sq mi). Maharashtra's population in 2020 is estimated at 123 million people (12.3 crores), according to the unique identity of Aadhar India, updated on May 31, 2020, by mid-2020 the population is expected to be 123,144,223, India's second most democratic state after Uttar Pradesh, 9% of the Indian population lives in Maharatrash. Mumbai is the financial capital and financial capital of India and the most popular city with 20 million people in 2019. It has a long coastline stretching nearly 720 km along the Arabian Sea to the west, Goa and Karnataka to the south, Chhattisgarh and Telangana to the east. Maharashtra is the most economically developed country in India with a GDP value of USD 390 million in 2018-2019, sharing about 15%. Its per head is $2500. According to the 2016 Niti Aayog report, the total birth rate is 1.8. Photo Source: Maharashtrians In traditional dress welcoming Gudi Padwa, the bike rally in Mumbai Maharashtra is the third urbanized state among other states since before independence. According to the 1901 population survey, 19 million people were recorded in the state. The average population growth was 24.81 in the fifty years following the Indian population survey from 1951 to 2001. Population growth slowed to 15.99% in 2011 while that was 22.73% compared to 2001. -

College Codes (Outside the United States)

COLLEGE CODES (OUTSIDE THE UNITED STATES) ACT CODE COLLEGE NAME COUNTRY 7143 ARGENTINA UNIV OF MANAGEMENT ARGENTINA 7139 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF ENTRE RIOS ARGENTINA 6694 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF TUCUMAN ARGENTINA 7205 TECHNICAL INST OF BUENOS AIRES ARGENTINA 6673 UNIVERSIDAD DE BELGRANO ARGENTINA 6000 BALLARAT COLLEGE OF ADVANCED EDUCATION AUSTRALIA 7271 BOND UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7122 CENTRAL QUEENSLAND UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7334 CHARLES STURT UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6610 CURTIN UNIVERSITY EXCHANGE PROG AUSTRALIA 6600 CURTIN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY AUSTRALIA 7038 DEAKIN UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6863 EDITH COWAN UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7090 GRIFFITH UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6901 LA TROBE UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6001 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6497 MELBOURNE COLLEGE OF ADV EDUCATION AUSTRALIA 6832 MONASH UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7281 PERTH INST OF BUSINESS & TECH AUSTRALIA 6002 QUEENSLAND INSTITUTE OF TECH AUSTRALIA 6341 ROYAL MELBOURNE INST TECH EXCHANGE PROG AUSTRALIA 6537 ROYAL MELBOURNE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AUSTRALIA 6671 SWINBURNE INSTITUTE OF TECH AUSTRALIA 7296 THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA 7317 UNIV OF MELBOURNE EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 7287 UNIV OF NEW SO WALES EXCHG PROG AUSTRALIA 6737 UNIV OF QUEENSLAND EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 6756 UNIV OF SYDNEY EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 7289 UNIV OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA EXCHG PRO AUSTRALIA 7332 UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE AUSTRALIA 7142 UNIVERSITY OF CANBERRA AUSTRALIA 7027 UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES AUSTRALIA 7276 UNIVERSITY OF NEWCASTLE AUSTRALIA 6331 UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND AUSTRALIA 7265 UNIVERSITY -

Status with Intake of Architectural Institutions in India As on June 29, 2018

STATUS WITH INTAKE OF ARCHITECTURAL INSTITUTIONS IN INDIA AS ON JUNE 29, 2018 S. Name & Address with Inst. Code. Affiliating Name of the Year of Current Intake No. University Course commen- & Approval cement of period course ANDHRA PRADESH 1. AP02 (Ar.) Ms. REVATHI DEVI ALLU Head of Department of Architecture, College of Engineering Andhra University, Andhra University, Waltair Visakhapatnam B. Arch. 1992 VISAKHAPATNAM-530 003,(Andhra Pradesh) Andhra Pradesh 40 Tel (O): 0891-2754586, 2844999 2018-2019 2844973, 2844974 & 75 Mb.09849349020-HOD Fax: 0891-2747969, 2525611 E-Mail: [email protected], [email protected] 2. AP05 (Ar.) Ms. Swapna T Principal JNA&FAU S.A.R. College of Architecture Hyderabad Revenue Survey No.132 Telangana B. Arch. 2002 --- Agiripally Village & Mandal KRISHNA DISTT. - 521 211(Andhra Pradesh) Tel (O): 08656-224770/1/2, 224727 Fax: 08656-224772, 8125474424 E-Mail: [email protected],[email protected] 3. AP08 (Ar.) Mr. C.S. SRINIVAS Head of Department ANU College of Architecture & Planning Acharya Nagarjuna Acharya Nagarjuna University 40 University, Nagarjuna Nagar B. Arch. 2009 2018-2019 GUNTUR GUNTUR-522 510 (Andhra Pradesh) Andhra Pradesh Tel: (O) 0863-2346525-26/505, 2346102,Mob: 07386186548, 09849082055, Fax: 0863-2293320 E-Mail: [email protected]@yahoo.com 4. AP11 B. Arch. 2011 (Ar.) Mr. K.MOHAN 80 Director 2018-2019 School of Architecture Gandhi Institute of Technology and Management Deemed to be (GITAM), (Deemed to be University) University Rushikonda Visakhapatnam Visakhapatnam-530 045, Andhra Pradesh Andhra Pradesh M. Arch. 2017 Tel: 0891-2840556, 2840501, Fax: 0891-2790339 20 (Sustainable Director’s cell: 09866668220,09866449926 2018-2019 E-mail: [email protected] Architecture) [email protected] [email protected] 5. -

Dr. Virendra Nagarale TEACHING EXPERIENCE: 25 Years

Dr. Virendra Nagarale Professor in Geography Department of Geography, S.N.D.T. Women’s University Karve Road PUNE (INDIA) 411038 Contact: Mobile- +919422360297 & +919823118968 Email: [email protected] and [email protected] ORCID ID https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7194-8718 SCOPUS AUTHOR ID: 5548907900 EDUCATION • Ph.D., Geography (Geomorphology) from North Maharashtra University Jalgaon in 2008 • M.Sc. Geography (Geomorphology) University of Pune, Pune, 1995 • LLB (Bachelor of Law) University of Pune, Pune, 2012 • PGDCL (Post Graduate Diploma in Cyber Law), Bharati Vidyapeeth, Pune ACADEMIC HONORS AND AWARDS • Recipient, ‘Prof. B. Hema Malini Eminent Geographer Award 2019’ by National Association of Geographers, India (NAGI), December 2019. • Recipient, ‘Best Teacher Award 2011’ by Pune Municipal Corporation (PMC) Pune TEACHING EXPERIENCE: 25 Years University Head of the Department July 2008 to May 2018 Coordinator: Post Graduate Studies and Research, PUNE 2017 to 2019 Member • Academic Council, SNDT Women’s University, 2017 to 2022. • RRC, University of Mumbai, Mumbai, 2018 to 2022. • RRC, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Marathwada University, Aurangabad, 2018 to 2022. • RRC, Swami Ramanand Teerth Marathwada University, Nanded, 2018 to 2022. • B.O.S. in Geography, S.P College (Autonomous) Pune, 2019 onwards. • B.O.S. in Geography, Modern College (Autonomous) Shivajinagar Pune 2019 onwards. • B.O.S. in Geography, M. J. College (Autonomous) Jalgaon 2019 onwards. • B.O.S. in Geography, Vivekananda College (Autonomous) Kolhapur, 2018 to 2021. • B.O.S. in Geography,S.P.Chowgule College (Autonomous) Madgaon Goa, 2017 to 2019 • B.O.S. in Geography, Mumbai University, Mumbai 2016 to 2018 • IQAC, SNDT Women’s University.