Thesis 207 Bibliography 213 Vi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rohan Prithvii, Ghatkopar West, Lal Bahadur Shastri Marg, Mumbai Fact Sheet

Rohan Prithvii, Ghatkopar West, Lal Bahadur Shastri Marg, Mumbai Fact Sheet Brochure Rohan Prithvii, Mumbai Brochure may be downloaded from the link: http://zrks.in/230169e6 Overview Lifescapes Prithvii is designed to marry luxurious living spaces within to scenic natural beauty outside. The project is meant for people who like space. The Project is tucked away off LBS Marg in Ghatkopar West. Close to the project, at a 3-minute drive, is the upcoming Asalfa Metro Station. So, once the Versova-Andheri-Ghatkopar Metro is operational, you can hope to reach the Western Suburbs in approximately 20 minutes. Project USP A completely gated community that promotes a sense of community living along with privacy Project provides all the basic amenities that are required to meet all your needs 3-tiered stringent security measures to ensure the safety of all students Covered parking area with reserved spaces for all residents Separate parking spaces for all guests and visitors Several civic amenities such as premium schools, medical centers and hospitality outlets in the neighbourhood Lush green surroundings and exquisite landscaping around the residential units 100 % power back up for building and all common facilities to ensure smooth and uninterrupted running of the same Location Advantages Located at Ghatkopar, Lal Bahadur Shastri Marg, Mumbai Easy connectivity to major areas of city Major schools and hospitals situated at a distance of 5 km Schools and Universities are in proximity to the society Facts Builder Name Rohan Lifescapes Price Range 1.25 Cr to 3.10 Cr Size Range 1315 - 2052 Sq.Ft Property Type Apartment Flat Type , 2 BHK , 3 BHK Project Status Under Construction Possesion Date Quarter 4 2018 Project Span 2 Acres No of Towers 4 Total No of Units 177 Unit Details Property Type Unit Type Saleable Area Floor Plan Apartment 2 BHK 1315 Sq. -

1. INTRODUCTION the Importance of River Can Be Traced Way Back Into

1. INTRODUCTION The importance of river can be traced way back into history. The nomadic Stone Age man always wandered around rivers. The world’s greatest civilizations have flourished on the banks of rivers. The Nile River was a key for the development of Ancient Egypt, the Indus River for the development of Mohenjo-Daro civilization, the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers for the development of Mesopotamian cultures, the Tiber River for Ancient Rome, etc. Ever since man learnt the benefits of rivers, he has used the river for various purposes like drinking, domestic use, irrigation, navigation, fishing, etc. As man advanced he invented new techniques to exploit river waters. With the advent of industrialization, the river water was now being used as a way to dispose of industrial waste, sewage and other domestic waste. Today, success of human civilization in developing or under developing countries mostly depends upon its industrial productivity that leads to economic progress of the country. Urbanization, globalization and industrialization all have an indirect or not specifically intended effect on ecosystem (Tanner et al., 2001). The disposal of human waste is another great challenge in both developed and developing countries (Zimmel et al. 2004).Waterways have been considered as convenient, cheapest and effective path for disposal of human waste. Aquatic ecosystems have been threatened worldwide by pollution and non unsustainable land use. Effect of poor quality of water on human health was noted first time in1854 by John Snow when he traced the outburst of cholera epidemic in London Thames River which was polluted to a great extent by sewage. -

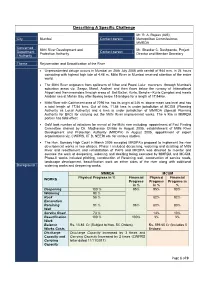

Describing a Specific Challenge

Describing A Specific Challenge Mr. R. A. Rajeev (IAS), City Mumbai Contact person Metropolitan Commissioner, MMRDA Concerned Mithi River Development and Mr. Shankar C. Deshpande, Project Department Contact person Protection Authority Director and Member Secretary / Authority Theme Rejuvenation and Beautification of the River • Unprecedented deluge occurs in Mumbai on 26th July 2005 with rainfall of 944 mm. in 24 hours coinciding with highest high tide of 4.48 m. Mithi River in Mumbai received attention of the entire world. • The Mithi River originates from spillovers of Vihar and Powai Lake traverses through Mumbai's suburban areas viz. Seepz, Marol, Andheri and then flows below the runway of International Airport and then meanders through areas of Bail Bazar, Kurla, Bandra - Kurla Complex and meets Arabian sea at Mahim Bay after flowing below 15 bridges for a length of 17.84Km. • Mithi River with Catchment area of 7295 ha. has its origin at 246 m. above mean sea level and has a total length of 17.84 kms. Out of this, 11.84 kms is under jurisdiction of MCGM (Planning Authority as Local Authority) and 6 kms is under jurisdiction of MMRDA (Special Planning Authority for BKC) for carrying out the Mithi River improvement works. The 6 Km in MMRDA portion has tidal effect. • GoM took number of initiatives for revival of the Mithi river including appointment of Fact Finding Committee chaired by Dr. Madhavrao Chitale in August 2005, establishment of Mithi River Development and Protection Authority (MRDPA) in August 2005, appointment of expert organisations viz. CWPRS, IIT B, NEERI etc. for various studies. -

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

PDF Generation Date :- Thu, 02 Sep 2021 08:13:27

PDF of Trial CTRI Website URL - http://ctri.nic.in Clinical Trial Details (PDF Generation Date :- Thu, 23 Sep 2021 19:22:35 GMT) CTRI Number CTRI/2017/11/010690 [Registered on: 29/11/2017] - Trial Registered Prospectively Last Modified On 26/04/2021 Post Graduate Thesis No Type of Trial Interventional Type of Study Drug Study Design Randomized, Parallel Group, Active Controlled Trial Public Title of Study A clinical trial to study the efficacy and safety of Atezolizumab compared with standard Chemotherapy in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer patients with poor performance status. Scientific Title of A Phase III, open-label, multicenter, randomized study to investigate the efficacy and safety of Study Atezolizumab compared with Chemotherapy in patients with treatment-naïve advanced or recurrent (Stage IIIb not amenable for multimodality treatment) or Metastatic (Stage IV) Non-small Cell Lung Cancer who are deemed unsuitable for platinum-containing Therapy Secondary IDs if Any Secondary ID Identifier Version 1.0 dated 13 Feb 2017 Protocol Number Details of Principal Details of Principal Investigator Investigator or overall Name Dr Raju Titus Chacko Trial Coordinator (multi-center study) Designation Head & Professor - Medical Oncology Affiliation Address Department of Medical Oncology, Christian Medical College, Ida Scudder Road Vellore TAMIL NADU 632004 India Phone 914162283040 Fax 914163073410 Email [email protected] Details Contact Details Contact Person (Scientific Query) Person (Scientific Name Dr Raeesuddin Syed Query) Designation Medical Chapter Lead - Medical Affairs Affiliation Roche Products (India) Pvt. Ltd. Address 146-B, 166 A, Unit No. 7, 8, 9 8th Floor, R City Office, R City Mall, Lal Bahadur Shastri Marg, Ghatkopar, Mumbai - 400 086, Maharashtra, India Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400051 India Phone 912233941414 Fax 912233941054 Email [email protected] Details Contact Details Contact Person (Public Query) Person (Public Query) Name Priyanka Bhattacharya Designation Lead– Clinical Operations Affiliation Roche Products (India) Pvt. -

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

India Architecture Guide 2017

WHAT Architect WHERE Notes Zone 1: Zanskar Geologically, the Zanskar Range is part of the Tethys Himalaya, an approximately 100-km-wide synclinorium. Buddhism regained its influence Lungnak Valley over Zanskar in the 8th century when Tibet was also converted to this ***** Zanskar Desert ཟངས་དཀར་ religion. Between the 10th and 11th centuries, two Royal Houses were founded in Zanskar, and the monasteries of Karsha and Phugtal were built. Don't miss the Phugtal Monastery in south-east Zanskar. Zone 2: Punjab Built in 1577 as the holiest Gurdwara of Sikhism. The fifth Sikh Guru, Golden Temple Rd, Guru Arjan, designed the Harmandir Sahib (Golden Temple) to be built in Atta Mandi, Katra the centre of this holy tank. The construction of Harmandir Sahib was intended to build a place of worship for men and women from all walks *** Golden Temple Guru Ram Das Ahluwalia, Amritsar, Punjab 143006, India of life and all religions to come and worship God equally. The four entrances (representing the four directions) to get into the Harmandir ਹਰਿਮੰਦਿ ਸਾਰਹਬ Sahib also symbolise the openness of the Sikhs towards all people and religions. Mon-Sun (3-22) Near Qila Built in 2011 as a museum of Sikhism, a monotheistic religion originated Anandgarh Sahib, in the Punjab region. Sikhism emphasizes simran (meditation on the Sri Dasmesh words of the Guru Granth Sahib), that can be expressed musically *** Virasat-e-Khalsa Moshe Safdie Academy Road through kirtan or internally through Nam Japo (repeat God's name) as ਰਿਿਾਸਤ-ਏ-ਖਾਲਸਾ a means to feel God's presence. -

MAHARASHTRA Not Mention PN-34

SL Name of Company/Person Address Telephone No City/Tow Ratnagiri 1 SHRI MOHAMMED AYUB KADWAI SANGAMESHWAR SANGAM A MULLA SHWAR 2 SHRI PRAFULLA H 2232, NR SAI MANDIR RATNAGI NACHANKAR PARTAVANE RATNAGIRI RI 3 SHRI ALI ISMAIL SOLKAR 124, ISMAIL MANZIL KARLA BARAGHAR KARLA RATNAGI 4 SHRI DILIP S JADHAV VERVALI BDK LANJA LANJA 5 SHRI RAVINDRA S MALGUND RATNAGIRI MALGUN CHITALE D 6 SHRI SAMEER S NARKAR SATVALI LANJA LANJA 7 SHRI. S V DESHMUKH BAZARPETH LANJA LANJA 8 SHRI RAJESH T NAIK HATKHAMBA RATNAGIRI HATKHA MBA 9 SHRI MANESH N KONDAYE RAJAPUR RAJAPUR 10 SHRI BHARAT S JADHAV DHAULAVALI RAJAPUR RAJAPUR 11 SHRI RAJESH M ADAKE PHANSOP RATNAGIRI RATNAGI 12 SAU FARIDA R KAZI 2050, RAJAPURKAR COLONY RATNAGI UDYAMNAGAR RATNAGIRI RI 13 SHRI S D PENDASE & SHRI DHAMANI SANGAM M M SANGAM SANGAMESHWAR EHSWAR 14 SHRI ABDULLA Y 418, RAJIWADA RATNAGIRI RATNAGI TANDEL RI 15 SHRI PRAKASH D SANGAMESHWAR SANGAM KOLWANKAR RATNAGIRI EHSWAR 16 SHRI SAGAR A PATIL DEVALE RATNAGIRI SANGAM ESHWAR 17 SHRI VIKAS V NARKAR AGARWADI LANJA LANJA 18 SHRI KISHOR S PAWAR NANAR RAJAPUR RAJAPUR 19 SHRI ANANT T MAVALANGE PAWAS PAWAS 20 SHRI DILWAR P GODAD 4110, PATHANWADI KILLA RATNAGI RATNAGIRI RI 21 SHRI JAYENDRA M DEVRUKH RATNAGIRI DEVRUK MANGALE H 22 SHRI MANSOOR A KAZI HALIMA MANZIL RAJAPUR MADILWADA RAJAPUR RATNAGI 23 SHRI SIKANDAR Y BEG KONDIVARE SANGAM SANGAMESHWAR ESHWAR 24 SHRI NIZAM MOHD KARLA RATNAGIRI RATNAGI 25 SMT KOMAL K CHAVAN BHAMBED LANJA LANJA 26 SHRI AKBAR K KALAMBASTE KASBA SANGAM DASURKAR ESHWAR 27 SHRI ILYAS MOHD FAKIR GUMBAD SAITVADA RATNAGI 28 SHRI -

E\Fyba\Fyba Political S

31 F.Y.B.A. POLITICALPAPER - I INDIAN POLITICAL SYSTEM SEMESTER - II SUB TITLE - INDIAN POLITICAL PROCESS SUBJECT CODE : UBA 2.25 © UNIVERSITY OF MUMBAI Prof. Suhas Pednekar Vice-Chancellor, University of Mumbai, Prof. Ravindra D. Kulkarni Prof. Prakash Mahanwar Pro Vice-Chancellor, Director, University of Mumbai, IDOL, University of Mumbai, Programme Co-ordinator : Anil R. Bankar Associate Professor of History and Head Faculty of Arts, IDOL, University of Mumbai Course Co-ordinator : Mr. Bhushan R. Thakare Assistant Prof. IDOL, University of Mumbai, Mumbai-400 098 Course Writer : Dr.Ravi Rameshchandra Shukla (Editor) Asst. Prof. & Head, Dept. of Political Science R.D. and S.H. National College and S.W.A. Science College , Bandra (W), Mumbai : Vishakha Patil Asst. Prof. Kelkar Education Trust's V.G.Vaze College of Arts, Science and Commerce, Mithagar Road, Mulund (W), Mumbai : Mr. Roshan Maya Verma Asst. Prof. Habib Educational and Welfare Society's M.S. College of Law : Mr.Aniket Mahendra Rajani Salvi Asst. Prof. Department of Political Science Bhavans College,Andheri (W), Mumbai March 2021, Print - I Published by : Director, Institute of Distance and Open Learning , University of Mumbai, Vidyanagari, Mumbai - 400 098. DTP Composed : Ashwini Arts Vile Parle (E), Mumbai - 400 099. Printed by : CONTENTS Unit No. Title Page No. Semester - II 1. Indian Federal System 01 2. Party and Party Politics in India 16 3. Social Dynamics 21 4. Criminalisation of Politics 44 I 1 Unit -1 INDIAN FEDERAL SYSTEM Unit Structure 1.1 Objectives 1.2 Introduction 1.3 Meaning and Definition 1.4 Characteristics of Indian Federalism 1.1OBJECTIVES: To study and understand the concept of federalism. -

Between Mumbai and Manila

Manfred Hutter (ed.) Between Mumbai and Manila Judaism in Asia since the Founding of the State of Israel (Proceedings of the International Conference, held at the Department of Comparative Religion of the University of Bonn. May 30, to June 1, 2012) V&R unipress Bonn University Press Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. 296’.095’0904–dc23 ISBN 978-3-8471-0158-1 ISBN 978-3-8470-0158-4 (E-Book) Publications of Bonn University Press are published by V&R unipress GmbH. Copyright 2013 by V&R unipress GmbH, D-37079 Goettingen All rights reserved, including those of translation into foreign languages. No part of this work may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, microfilm and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printing and binding: CPI Buch Bu¨cher.de GmbH, Birkach Printed in Germany Contents Manfred Hutter / Ulrich Vollmer Introductory Notes: The Context of the Conference in the History of Jewish Studies in Bonn . ................... 7 Part 1: Jewish Communities in Asia Gabriele Shenar Bene Israel Transnational Spaces and the Aesthetics of Community Identity . ................................... 21 Edith Franke Searching for Traces of Judaism in Indonesia . ...... 39 Vera Leininger Jews in Singapore: Tradition and Transformation . ...... 53 Manfred Hutter The Tiny Jewish Communities in Myanmar, Thailand and Cambodia . 65 Alina Pa˘tru Judaism in the PR China and in Hong Kong Today: Its Presence and Perception . -

Journal of the City and Regional Planning Department

FOCUS 10 Table of Contents A Note from the Department Head 3 FACULTY AND STUDENT WORK Editor’s Overview 4 Cal Poly Wins Again: Bank of America/Merrill Lynch Low Income Housing Challenge 85 A Planner’s Perspective 5 Andrew Levin Ask No Small Question Chris Clark Planning and Design for Templeton 88 Cartoon Corner 8 Emily Gerger Mumbai Port and City 91 SPECIAL SECTION Hemalata Dandekar and Sulakshana Mahajan Designing Resiliency in an Unsustainable World 11 Portland-Milwaukie Light Rail Transit Project: Managing Winter 2013 Hearst Lecture Lewis Knight Growth Sustainably through Transit Alternatives 99 Stephan Schmidt and Kayla Gordon The Ethics of Navigating Complex Communities 20 Claudia Isaac Preparing a Local Harzard Mitigation Plan: A Case Study in Watsonville, California 104 California Climate Action Planning Conference 27 Emily Lipoma Michael Boswell Improving Small Cities in California: ESSAYS Clearlake and Bell 110 William Siembieda Planning for a Strategic Gualadalajara: Towards a Sustainable and Competitive Metropolis 31 Ian Nairn, Townscape and the Campaign Francisco Perez Against Subtopia 113 Lorenza Pavesi On the Art and Practice of Urban Design 43 John Decker Designing a Sustainable Future for Vietnam 121 Abraham Sheppard Cal Poly’s Sustainability Program: What is Its Effect on Students? 53 SPOTLIGHT Daniel Levi and Rebecca Sokoloski Learning from California: Competitions in Arquitecture and Urban Design 57 Highlights of CRP Studios, 2012/2013 131 Miguel Baudizzone Hemalata Dandekar Regional Governance in the San Francisco