Adventists and Biological Warfare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Military Service--A Comparative Study Between the New Testament Teaching and the Attitude of German Adventists

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Master's Theses Graduate Research 1993 Military Service--a Comparative Study Between the New Testament Teaching and the Attitude of German Adventists Johannes Hartlapp Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses Recommended Citation Hartlapp, Johannes, "Military Service--a Comparative Study Between the New Testament Teaching and the Attitude of German Adventists" (1993). Master's Theses. 40. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses/40 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

The Pentagon Bio-Weapons

The Pentagon Bio-Weapons https://southfront.org/pentagon-bio-weapons/ ANALYSIS #USAEditor's choice DilyanaGaytandzhieva is a Bulgarian investigative journalist and Middle East Correspondent. Over the last two years she has published a series of revealed reports on weapons smuggling. In the past year she came under pressure from the Bulgarian National Security Agency and was fired from her job in the Bulgarian newspaper Trud Daily without explanation. Despite this, Dilyana continues her investigations. Her current report provides an overview of Pentagon’s vigour in the development of biological weapons. Twitter/@dgaytandzhieva (Here is a topic long suspected, but never ‘brought to light’ until now. Don't expect to see such an article in the Main Stream media [MSM] as it would be censored and/or heavily edited before being published. The level of details provided by the author makes her case irrefutable! Those that would like better documentation, can go to the website cited, as virtually EVERY photo, document, map, etc., is enlargeable.. Downloaded from the above website on Feb 10, 2018 ~ Don Chapin) The US Army regularly produces deadly viruses, bacteria and toxins in direct violation of the UN Convention on the prohibition of Biological Weapons. Hundreds of thousands of unwitting people are systematically exposed to dangerous pathogens and other incurable diseases. Bio warfare scientists using diplomatic cover test man-made viruses at Pentagon bio laboratories in 25 countries across the world. These US bio-laboratories are funded by the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) under a $ 2.1 billion military program– Cooperative Biological Engagement Program (CBEP), and are located in former Soviet Union countries such as Georgia and Ukraine, the Middle East, South East Asia and Africa. -

The Triangle 1941

Southern Adventist University KnowledgeExchange@Southern Yearbooks University Archives & Publications 1941 The Triangle 1941 Southern Junior College Follow this and additional works at: https://knowledge.e.southern.edu/yearbooks Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Southern Junior College, "The Triangle 1941" (1941). Yearbooks. 11. https://knowledge.e.southern.edu/yearbooks/11 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives & Publications at KnowledgeExchange@Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yearbooks by an authorized administrator of KnowledgeExchange@Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -'SJw TAKE" NOT TO BE FROM LIBRARY ii >< ** S&Sfo rul'«'"r>l-".~*( Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from Lyrasis Members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/triangle1941coll 1HFw RIRNGLE^ PUBLISHED BY THE STUDENT BODY of SOUTHERN JUNIOR COLLEGE RHODODENDRON IN BLOOM L,U 5101 S367 A12 1941 (SDA) c N T E N T S FOREWORD CONTENTS TRIANGLE STAFF DEDICATION CAMPUS POWERS THAT BE CLASSES SENIORS JUNIORS UNDERGRADUATES ACTIVITIES DAILY BREAD ADVERTISEMENTS /f /^n? TRIANGLE STAFF Editor-in-Chief Lorabel Peavey Associate Editor Wayne Foster Business Manager Wayne Satterfield Class Activities Editor Donald West Social Activities Editor Benjamin E. Herndon Religious Activities Editor Alvin Stewart Picture Editors T. J. Shelton Marian Allen Art Editors Kathryn Roper Kathryn Shropshire Circulation Manager Maxine Hayes Faculty Advisors Dean Rudolph Johnson Miss Theodora Wirak DEDICATION In appreciation of the unending love and devotion,- for the many sacrifices made for our enjoyment; for the prayers in our behalf; for guidance and protection through our hesitant steps,- for loving care during illness,- and because we love you, dear parents of the student body o Southern Junior College, we dedi- mil cate this annual. -

Anthrax Plague Tularemia

July 29, 2019 Paula Bryant Acting Director, OBRRTR OBRRTR in DMID Office of the Director Clinical Research Coordination Office of Office of Office of Office of Office of Office of Biodefense, Scientific Clinical Clinical Genomics Regulatory Research Resources, Coordination Research Research and Advanced Affairs and Translational and Program Affairs Resources Technologies Research (OBRRTR) Operations Parasitology and Enterics & Sexually Bacteriology and Respiratory International Transmitted Virology Branch Mycology Branch Diseases Branch Programs Infections Branch Branch HHS Priority Biological Threats* NIAID Cat A NIAID Cat B NIAID Cat C Bacillus anthracis (anthrax) Burkholderia mallei (glanders) Antimicrobial resistance MDR anthrax Burkholderia pseudomallei Pandemic influenza Smallpox (melioidosis) Ebola virus Rickettsia prowazekii (typhus) Marburg virus Yersinia pestis (plague) Francisella tularensis (tularemia) Clostridium botulinum toxin (BoNT) Emerging infectious diseases (EID) – ‘Disease X’ Other VHFs (Junin, Machupo, Alphaviruses (WEE,EEE,VEE) Lassa, RVF) Ricin, Brucellosis, SEB, Q-fever Yellow Fever Additional DoD and/or lower priority *PHEMCE SIP 2017-18 From OBRA to OBRRTR Broad spectrum MCMs & Narrow-spectrum MCMs Enabling Platform for CatA-BioD Technologies for CatA-C BioD & EID preparedness OBRRTR’s Role 1. ‘PHEMCE’: Address USG’s identified biodefense and public health needs • Execute and represent NIH’s BioD and public health emergency R&D to the PHEMCE 2. Product Development: advance candidate MCMs and Platform Technologies late preclinical, IND/IDE- Phase I clinical testing, enabling testing & mfg with Phase II capabilities • Biothreats = PHEMCE requirements based on DHS assessments • EID’s and other public health threats • Regulatory path - accelerated approval, Animal rule, or EUA • Transition to BARDA, DoD or industry 3. Translational Research: facilitate and manage…. -

Medical Cadet Corps Training Is Important

official organ of the Pacific Union Conference of Seventh-day Adventists MR. AND MRS. GEORGE ADAMS JOIN FAITH FOR TODAY STAFF Recently George Adams joined the Faith for Today production staff to become the third film editor. Born in Illinois, George Adams later moved to Texas where he spent several years at Southwestern Union College. He recently graduated from Southern Mission- ary College with a B.A. degree in com- PACIFIC UNION munications. He also helped with the ARIZONA • CALIFORNIA • HAWAII • NEVADA • UTAH closed-circuit television production at the college. VOL. 70 ANGWIN, CALIFORNIA, JULY 9, 1970 NO. 2 Voice of Prophecy in Need Medical Cadet Corps Training Is Important of Specialized Volunteers Due to unusual increase in response to Every day as I answer my mail and the of the confusion in the minds of our youth, its outreach for souls, The Voice of Proph- many telephone calls that deal with ques- end to help them make the right decisions. ecy is in critical need of specialized vol- tions about Selective Service and military The final decision, however, is left to the unteers who want to do something excep- obligations, it makes me more convinced individual as to how he must serve God tional for God. than ever that every Seventh-day Adventist and his country. Are you a keypunch operator? If you young man facing a decision on his mili- Parents with sons who are at least six- are, and want to volunteer in a very spe- tary obligation needs to avail himself of the teen years of age should do everything in cialized Christian service, either evenings Medical Cadet Corps training offered him their power to get their sons into the Med- or Sundays, we invite you to write or call by his church. -

An Analysis of Adventist Mission Methods in Brazil in Relationship to a Christian Movement Ethos

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2016 An Analysis of Adventist Mission Methods in Brazil in Relationship to a Christian Movement Ethos Marcelo Eduardo da Costa Dias Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Missions and World Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Costa Dias, Marcelo Eduardo da, "An Analysis of Adventist Mission Methods in Brazil in Relationship to a Christian Movement Ethos" (2016). Dissertations. 1598. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/1598 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT AN ANALYSIS OF ADVENTIST MISSION METHODS IN BRAZIL IN RELATIONSHIP TO A CHRISTIAN MOVEMENT ETHOS by Marcelo E. C. Dias Adviser: Bruce Bauer ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: AN ANALYSIS OF ADVENTIST MISSION METHODS IN BRAZIL IN RELATIONSHIP TO A CHRISTIAN MOVEMENT ETHOS Name of researcher: Marcelo E. C. Dias Name and degree of faculty chair: Bruce Bauer, DMiss Date completed: May 2016 In a little over 100 years, the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Brazil has grown to a membership of 1,447,470 (December 2013), becoming the country with the second highest total number of Adventists in the world. Very little academic research has been done to study or analyze the growth and development of the Adventist church in Brazil. -

The Organizational Structure

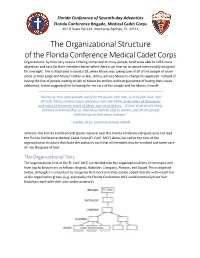

Florida Conference of Seventh-day Adventists Florida Conference Brigade, Medical Cadet Corps 351 S State Rd 434, Altamonte Springs, FL 32714 The Organizational Structure of the Florida Conference Medical Cadet Corps Organizations, by their very nature of being comprised of many people, tend to be able to fulfill more objectives and care for their members better when there is an internal structure intentionally designed for oversight. This is illustrated in Exodus 18, when Moses was taking care of all of the people of Israel alone as their judge and Moses’ Father-in-law, Jethro, advises Moses to change his approach. Instead of having the line of people waiting to talk to Moses be endless without guarantee of having their issues addressed, Jethro suggested the following for the care of the people and for Moses, himself: “Moreover thou shalt provide out of all the people able men, such as fear God, men of truth, hating covetousness; and place such over them, to be rulers of thousands, and rulers of hundreds, rulers of fifties, and rulers of tens: …If thou shalt do this thing, and God command thee so, then thou shalt be able to endure, and all this people shall also go to their place in peace.” - Exodus 18:21, 23 KJV (emphasis added) Similarly, the Florida Conference Brigadier General over the Florida Conference Brigade does not lead the Florida Conference Medical Cadet Corps (FL Conf. MCC) alone, but rather the tiers of the organizational structure distribute the authority such that all members may be involved and taken care of—by the grace of God. -

The Light Shines in West Africa

oircc2 HERALD-51 GENERAL CHURCH PAPER OF Ew THE SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTISTS A group of soul-winning evangelists of the Gold Coast Mission, West Africa. The Light Shines in West Africa By J. 0. GIBSON President, West African Union Mission HE keynote of our work here in West Africa is responsibility of following up these efforts, in order that evangelism. Every field and institution has as its these souls may be prepared for baptism and become Tprimary aim the spreading of the gospel to the strong church members in the months or years to come. forty-two million people in our territory. Certainly the H. S. Pearce, the manager of the newly opened Advent harvest is ripe, but the laborers are few. We thank God Press here in Accra, has been assisting in one of these for the group of consecrated evangelists, teachers, and efforts. It appears that the man who owned the meet- institutional workers who have the burden to carry the ing hall where the effort was held will, among many gospel of Jesus Christ to these needy millions. others, give his heart to Christ. I also had the privilege The Gold Coast Mission has just completed its Au- of assisting in one of these efforts. I presented the Sab- gust evangelism, which is a spearhead type of evangelism. bath question, and among others who responded to keep During the month of August the schoolteachers, evan- God's true Sabbath holy was the principal of the com- gelists, institutional workers, and laymen joined together mercial college where the effort was being held in this in conducting forty-one of these efforts. -

Transparency in Past Offensive Biological Weapon Programmes

Transparency in past offensive biological weapon programmes An analysis of Confidence Building Measure Form F 1992-2003 Nicolas Isla Occasional Paper No. 1 June 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive summary................................................................................................................................ 3 1. Introduction....................................................................................................................................... 5 2. Analysis and evaluation of declared data on past offensive BW programmes........................ 8 2.1. Canada....................................................................................................................................... 8 2.2. France........................................................................................................................................ 10 2.3. Iraq............................................................................................................................................. 13 2.4. Russian Federation................................................................................................................... 15 2.5. South Africa.............................................................................................................................. 18 2.6. United Kingdom...................................................................................................................... 20 2.7. United States............................................................................................................................ -

Medical Management of Biological Casualties Handbook

USAMRIID’s MEDICAL MANAGEMENT OF BIOLOGICAL CASUALTIES HANDBOOK Sixth Edition April 2005 U.S. ARMY MEDICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES FORT DETRICK FREDERICK, MARYLAND Emergency Response Numbers National Response Center: 1-800-424-8802 or (for chem/bio hazards & terrorist events) 1-202-267-2675 National Domestic Preparedness Office: 1-202-324-9025 (for civilian use) Domestic Preparedness Chem/Bio Helpline: 1-410-436-4484 or (Edgewood Ops Center – for military use) DSN 584-4484 USAMRIID’s Emergency Response Line: 1-888-872-7443 CDC'S Emergency Response Line: 1-770-488-7100 Handbook Download Site An Adobe Acrobat Reader (pdf file) version of this handbook can be downloaded from the internet at the following url: http://www.usamriid.army.mil USAMRIID’s MEDICAL MANAGEMENT OF BIOLOGICAL CASUALTIES HANDBOOK Sixth Edition April 2005 Lead Editor Lt Col Jon B. Woods, MC, USAF Contributing Editors CAPT Robert G. Darling, MC, USN LTC Zygmunt F. Dembek, MS, USAR Lt Col Bridget K. Carr, MSC, USAF COL Ted J. Cieslak, MC, USA LCDR James V. Lawler, MC, USN MAJ Anthony C. Littrell, MC, USA LTC Mark G. Kortepeter, MC, USA LTC Nelson W. Rebert, MS, USA LTC Scott A. Stanek, MC, USA COL James W. Martin, MC, USA Comments and suggestions are appreciated and should be addressed to: Operational Medicine Department Attn: MCMR-UIM-O U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) Fort Detrick, Maryland 21702-5011 PREFACE TO THE SIXTH EDITION The Medical Management of Biological Casualties Handbook, which has become affectionately known as the "Blue Book," has been enormously successful - far beyond our expectations. -

Fort Detrick, Frederick, MD

Fort Detrick, Frederick, MD FACT SHEET as of February 2018 Background: Fort Detrick encompasses approximately 1,200 acres divided among three areas in Frederick, Md. Area A is the largest, comprised of approximately 800 acres, and the primary area of construction activity. Most of the Fort Detrick facilities, tenants, post housing, and community facilities are located in Area A. The Forest Glen Annex, Silver Spring, Md., also falls under the operational control of Fort Detrick. The current Corps of Engineers design/construction program on Fort Detrick is approximately $724 million, featuring the $678-million U.S. Army Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) Replacement project, the only Department of Defense high-containment biological laboratory. Fort Detrick, originally named Camp Detrick until 1956, was established in 1931 as a military training airfield named after Maj. Frederick Detrick, a squadron surgeon. In 1943, the U.S. Biological Laboratories were established, pioneering efforts in decontamination, gaseous sterilization and agent purification. In 1969, Fort Detrick’s biological warfare research center mission was terminated and 69 acres of the installation were transferred to the Department of Health and Human Services to conduct cancer research. The installation has now matured into a multi-interagency campus (four cabinet level tenants) focusing on advanced bio-medical research and development, medical materiel management, and long-haul telecommunications for the White House, Department of Defense, and other governmental agencies. The National Interagency Biodefense Campus (NIBC) is currently the focal point of all activities on the installation, and the new USAMRIID project is the cornerstone of the campus. Names and phone numbers for significant installation points of contact are as follows: Congressional Rep (D-6th) John Delaney Congressional Rep (D-8th) Jamie Raskin Installation/MRMC Commander MG Barbara R. -

Nov03 POSTER1106.Indd

The National Cancer Institute Ft. Detrick’s 60th Anniversary story on page 3. News from the NCI-Frederick NOVEMBER 2003 Offi ce of Scientifi c Operations IN THIS ISSUE This year we celebrate the 60th Owned-Contractor Operated (GOCO) Ft. Detrick’s 60th Anniversary 3 anniversary of Fort (Ft.) Detrick. facility. Ft. Detrick’s roots can be traced to The fi rst employees of the NCI- Major Construction Projects 4 a small municipal airport known as Frederick (then known as the Detrick Field1, The Field was named Frederick Cancer Research Center) Building 470 Update 5 to honor Major Frederick L. Detrick, appeared on campus in June 1972 and who served in France during World numbered around 20 by the end of Scientifi c Publications, War I. The fi rst military presence at that month. By 1976 these numbers Graphics & Media News 6 the airfi eld was in 1931 when the had grown to about 750 individuals, Maryland National Guard established and by 1987 the staff numbered over Awards 6 a cadet pilot training center at Detrick 1,400 with a budget of nearly $100 Field and subsequently Platinum Publications 8 changed the name to Camp Detrick. Poster-Script 11 As we pause to think about the history of Ft. Did You Know? 12 Detrick and the many contributions that the Transfer Technology Branch 14 staff of Ft. Detrick has made in the areas of Community Outreach 15 infectious disease and national defense, it Offi ce of Diversity and seems that now is an Employee Programs 16 appropriate time to also look back at the history Environment, Health, and Safety of the NCI here at Ft.