Military Service--A Comparative Study Between the New Testament Teaching and the Attitude of German Adventists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

White, Mary Ellen Kelsey (1857-1890)

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Faculty Publications 2020 White, Mary Ellen Kelsey (1857-1890) Jerry A. Moon Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/pubs White, Mary Ellen Kelsey (1857–1890) JERRY A. MOON Jerry A. Moon, Ph.D., served as chair of the Church History Department in the Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary at Andrews University (2002- 2016) and as editor of Andrews University Seminary Studies (2000-2009). He co-edited The Ellen G. White Encyclopedia (Review and Herald, 2013) and co- authored The Trinity (Review and Herald, 2002). His dissertation, W. C. White and Ellen G. White: The Relationship between the Prophet and Her Son, was published by Andrews University Press in 1993. Article Title: White, Mary Ellen Kelsey (1857–1890) Author: Jerry A. Moon Mary (Kelsey) White, the first wife of William C. White, served as an editor, treasurer, and missionary. Early Life Mary Ellen Kelsey was born April 20, 1857, in Leroy Township near Battle Creek, Michigan. Mary’s mother, Eunice Rebecca [nee Bushnell] (1820-1906), was born in Old Saybrook, Middlesex County, Connecticut, USA. At the age of 13 Eunice witnessed the meteoric shower of 1833, and by 18 she had qualified herself as a public school teacher. Mary’s father, Asa Post H. Mary White Kelsey (1818-1857) was born in Schoharie, New York. Photo courtesy of Ellen G. White Estate, Inc. After their marriage, July 4, 1838, the Kelseys moved west to Leroy Township, Michigan, where Asa operated a saw mill. Under the ministry of Joseph Bates, the Kelseys became Sabbathkeepers in 1852 and charter members of the first Seventh-day Adventist church in Battle Creek, Michigan. -

HISTORY of SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST THEOLOGY Denis Kaiser, M.A., Ph.D

S EVENTH - D A Y A D V E N T I S T T HEOLOGICAL S EMINARY CHIS 674 HISTORY OF SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST THEOLOGY Denis Kaiser, M.A., Ph.D. cand. M.A. (Pastoral Ministry) Program Lincoln, Nebraska March 13-17, 2016 CHIS674 DEVELOPMENT OF SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST THEOLOGY MARCH 13-17, 2016 GENERAL CLASS INFORM ATION Class location: Mid-America Union: Piedmont Park Seventh-day Adventist Church 4801 A Street, Lincoln, NE 68510 ~ 402-489-1344 Class time/day: Sunday, March 13, 2016, 4:00-6:00 pm Mon.—Wed., 8:00 am-12:00 noon, and 1:30-5:30 pm Thursday, March 17, 8:00 am-12:30 pm. Credits offered: 3 INSTRUCTOR CONTACT Professor: Denis Kaiser, M.A., Ph.D. cand. Telephone: (269) 861-3049, cell, 8:00 am—8:00 pm only. Thank you! Email: [email protected] Office location: James White Library, Center for Adventist Research 161A Office hours: By appointment Admin. Assistant: Jenny Rojas, [email protected] 269-471-3209 Course materials: learninghub.andrews.edu COURSE DESCRIPTION The history and development of Seventh-day Adventist theology from the 1840s to the present, with emphasis on doctrines such as the Sabbath, sanctuary, conditional immortality, eschatology, covenants, Christology, righteousness by faith, and the gift of prophecy. The course utilizes blended learning to meet academic standards in a one-week intensive. Students will complete 15 hours of lectures by video outside of class, plus 30 hours during the intensive, for a total of 45 contact hours. S EVENTH - D A Y A D V E N T I S T T HEOLOGICAL S EMINARY 2 COURSE MATERIALS Required: Burt, Merlin D. -

The Triangle 1941

Southern Adventist University KnowledgeExchange@Southern Yearbooks University Archives & Publications 1941 The Triangle 1941 Southern Junior College Follow this and additional works at: https://knowledge.e.southern.edu/yearbooks Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Southern Junior College, "The Triangle 1941" (1941). Yearbooks. 11. https://knowledge.e.southern.edu/yearbooks/11 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives & Publications at KnowledgeExchange@Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yearbooks by an authorized administrator of KnowledgeExchange@Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -'SJw TAKE" NOT TO BE FROM LIBRARY ii >< ** S&Sfo rul'«'"r>l-".~*( Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from Lyrasis Members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/triangle1941coll 1HFw RIRNGLE^ PUBLISHED BY THE STUDENT BODY of SOUTHERN JUNIOR COLLEGE RHODODENDRON IN BLOOM L,U 5101 S367 A12 1941 (SDA) c N T E N T S FOREWORD CONTENTS TRIANGLE STAFF DEDICATION CAMPUS POWERS THAT BE CLASSES SENIORS JUNIORS UNDERGRADUATES ACTIVITIES DAILY BREAD ADVERTISEMENTS /f /^n? TRIANGLE STAFF Editor-in-Chief Lorabel Peavey Associate Editor Wayne Foster Business Manager Wayne Satterfield Class Activities Editor Donald West Social Activities Editor Benjamin E. Herndon Religious Activities Editor Alvin Stewart Picture Editors T. J. Shelton Marian Allen Art Editors Kathryn Roper Kathryn Shropshire Circulation Manager Maxine Hayes Faculty Advisors Dean Rudolph Johnson Miss Theodora Wirak DEDICATION In appreciation of the unending love and devotion,- for the many sacrifices made for our enjoyment; for the prayers in our behalf; for guidance and protection through our hesitant steps,- for loving care during illness,- and because we love you, dear parents of the student body o Southern Junior College, we dedi- mil cate this annual. -

Andrews University Press to Publish New Bible Commentary Keri Suarez Andrews University

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Lake Union Herald Lake Union Herald 7-2013 Andrews University Press to Publish New Bible Commentary Keri Suarez Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/luh-pubs Part of the Biblical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Suarez, Keri, "Andrews University Press to Publish New Bible Commentary" (2013). Lake Union Herald. 202. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/luh-pubs/202 This News is brought to you for free and open access by the Lake Union Herald at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Lake Union Herald by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEWS couldn’t. But you know, I think I Chippewa Valley can pray next time that happens.” Hospital is a place Another employee commented, “I like that we have a hospital where to pray we can be spiritual.” Wisconsin—Did you know there Miller prays every morning, is an Adventist hospital in Durand, “Lord, help me to be humble and Wis.? Chippewa Valley Hospital make an impact for You.” Then he and Oakview Care Center operate makes rounds to visit all the em- under the leadership of Adventist ployees and patients. “I just say ‘Hi,’ Juanita Edge ask how they’re doing, and offer members Doug Peterson, president Each morning, Art Miller (left) prays, “Lord, help me to pray with them. God opens the and CEO, and Art Miller, resident to make an impact for you.” He is resident chaplain at Chippewa Valley Hospital and Oakview Care doors from there.” chaplain. -

Medical Cadet Corps Training Is Important

official organ of the Pacific Union Conference of Seventh-day Adventists MR. AND MRS. GEORGE ADAMS JOIN FAITH FOR TODAY STAFF Recently George Adams joined the Faith for Today production staff to become the third film editor. Born in Illinois, George Adams later moved to Texas where he spent several years at Southwestern Union College. He recently graduated from Southern Mission- ary College with a B.A. degree in com- PACIFIC UNION munications. He also helped with the ARIZONA • CALIFORNIA • HAWAII • NEVADA • UTAH closed-circuit television production at the college. VOL. 70 ANGWIN, CALIFORNIA, JULY 9, 1970 NO. 2 Voice of Prophecy in Need Medical Cadet Corps Training Is Important of Specialized Volunteers Due to unusual increase in response to Every day as I answer my mail and the of the confusion in the minds of our youth, its outreach for souls, The Voice of Proph- many telephone calls that deal with ques- end to help them make the right decisions. ecy is in critical need of specialized vol- tions about Selective Service and military The final decision, however, is left to the unteers who want to do something excep- obligations, it makes me more convinced individual as to how he must serve God tional for God. than ever that every Seventh-day Adventist and his country. Are you a keypunch operator? If you young man facing a decision on his mili- Parents with sons who are at least six- are, and want to volunteer in a very spe- tary obligation needs to avail himself of the teen years of age should do everything in cialized Christian service, either evenings Medical Cadet Corps training offered him their power to get their sons into the Med- or Sundays, we invite you to write or call by his church. -

An Analysis of Adventist Mission Methods in Brazil in Relationship to a Christian Movement Ethos

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2016 An Analysis of Adventist Mission Methods in Brazil in Relationship to a Christian Movement Ethos Marcelo Eduardo da Costa Dias Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Missions and World Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Costa Dias, Marcelo Eduardo da, "An Analysis of Adventist Mission Methods in Brazil in Relationship to a Christian Movement Ethos" (2016). Dissertations. 1598. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/1598 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT AN ANALYSIS OF ADVENTIST MISSION METHODS IN BRAZIL IN RELATIONSHIP TO A CHRISTIAN MOVEMENT ETHOS by Marcelo E. C. Dias Adviser: Bruce Bauer ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: AN ANALYSIS OF ADVENTIST MISSION METHODS IN BRAZIL IN RELATIONSHIP TO A CHRISTIAN MOVEMENT ETHOS Name of researcher: Marcelo E. C. Dias Name and degree of faculty chair: Bruce Bauer, DMiss Date completed: May 2016 In a little over 100 years, the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Brazil has grown to a membership of 1,447,470 (December 2013), becoming the country with the second highest total number of Adventists in the world. Very little academic research has been done to study or analyze the growth and development of the Adventist church in Brazil. -

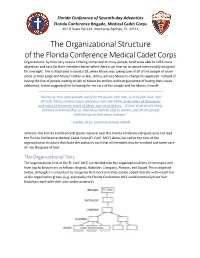

The Organizational Structure

Florida Conference of Seventh-day Adventists Florida Conference Brigade, Medical Cadet Corps 351 S State Rd 434, Altamonte Springs, FL 32714 The Organizational Structure of the Florida Conference Medical Cadet Corps Organizations, by their very nature of being comprised of many people, tend to be able to fulfill more objectives and care for their members better when there is an internal structure intentionally designed for oversight. This is illustrated in Exodus 18, when Moses was taking care of all of the people of Israel alone as their judge and Moses’ Father-in-law, Jethro, advises Moses to change his approach. Instead of having the line of people waiting to talk to Moses be endless without guarantee of having their issues addressed, Jethro suggested the following for the care of the people and for Moses, himself: “Moreover thou shalt provide out of all the people able men, such as fear God, men of truth, hating covetousness; and place such over them, to be rulers of thousands, and rulers of hundreds, rulers of fifties, and rulers of tens: …If thou shalt do this thing, and God command thee so, then thou shalt be able to endure, and all this people shall also go to their place in peace.” - Exodus 18:21, 23 KJV (emphasis added) Similarly, the Florida Conference Brigadier General over the Florida Conference Brigade does not lead the Florida Conference Medical Cadet Corps (FL Conf. MCC) alone, but rather the tiers of the organizational structure distribute the authority such that all members may be involved and taken care of—by the grace of God. -

The Light Shines in West Africa

oircc2 HERALD-51 GENERAL CHURCH PAPER OF Ew THE SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTISTS A group of soul-winning evangelists of the Gold Coast Mission, West Africa. The Light Shines in West Africa By J. 0. GIBSON President, West African Union Mission HE keynote of our work here in West Africa is responsibility of following up these efforts, in order that evangelism. Every field and institution has as its these souls may be prepared for baptism and become Tprimary aim the spreading of the gospel to the strong church members in the months or years to come. forty-two million people in our territory. Certainly the H. S. Pearce, the manager of the newly opened Advent harvest is ripe, but the laborers are few. We thank God Press here in Accra, has been assisting in one of these for the group of consecrated evangelists, teachers, and efforts. It appears that the man who owned the meet- institutional workers who have the burden to carry the ing hall where the effort was held will, among many gospel of Jesus Christ to these needy millions. others, give his heart to Christ. I also had the privilege The Gold Coast Mission has just completed its Au- of assisting in one of these efforts. I presented the Sab- gust evangelism, which is a spearhead type of evangelism. bath question, and among others who responded to keep During the month of August the schoolteachers, evan- God's true Sabbath holy was the principal of the com- gelists, institutional workers, and laymen joined together mercial college where the effort was being held in this in conducting forty-one of these efforts. -

A Movement of Authentic Christianity: an Embrace and Integration Of

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertation Projects DMin Graduate Research 2010 A Movement of Authentic Christianity: an Embrace and Integration of Biblical Fundamentals in a Seventh-day Adventist Church Plant Among the Echo Boomer Culture of the 21st Century in Keller, Texas Michael R. Cauley Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Recommended Citation Cauley, Michael R., "A Movement of Authentic Christianity: an Embrace and Integration of Biblical Fundamentals in a Seventh-day Adventist Church Plant Among the Echo Boomer Culture of the 21st Century in Keller, Texas" (2010). Dissertation Projects DMin. 30. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/30 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertation Projects DMin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT A MOVEMENT OF AUTHENTIC CHRISTIANITY: AN EMBRACE AND INTEGRATION OF BIBLICAL FUNDAMENTALS IN A SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH PLANT AMONG THE ECHO BOOMER CULTURE OF THE 21ST CENTURY IN KELLER, TEXAS by Michael R. Cauley Adviser: Bruce L. Bauer ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: A MOVEMENT OF AUTHENTIC CHRISTIANITY: AN EMBRACE AND INTEGRATION OF BIBLICAL FUNDAMENTALS IN A SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH PLANT AMONG THE ECHO BOOMER CULTURE OF THE 21ST CENTURY IN KELLER, TEXAS Name of researcher: Michael R. -

Adventist Review • Ett N

Adventist Review General Paper of the Seventh-day Adventist Church June 7, 1984 Pastors in uniform Page 3 Forgiveness in marriage Page 12 Adventists and military enlistment Page 14 The religion of President Reagan Page 20 Cover: Adventist chaplain James J. North, Jr., receives a flag from a serviceman's coffin to give to his next of kin. See This Week, page 2. THIS WEEK Corps. (See "Colonel Ever- Adventist Review • ett N. Dick, MCC," p. 8, and "A Medical Cadet Remembers " p. 10.) An area of contribution that may not be known so widely is Published continuously since 1849 the work of Adventist military EDITOR chaplains. Some of their experi- William G. Johnson ences are shared in "Pastors in ASSOCIATE EDITOR Uniform: Walking the Narrow George W. Reid Road," p. 3, and "A Chaplain MANAGING EDITOR Recalls . ," p. 6. Jocelyn R. Fay Bible credits: Texts in this ASSISTANT EDITORS issue credited to N.I.V. are James N. Coffin, Eugene F. Durand from The Holy Bible: New Aileen Andres Sox International Version. Copy- ADMINISTRATIVE SECRETARY right © 1978 by the Interna- Corinne Russ tional Bible Society. Used by EDITORIAL SECRETARIES Chaplain North gives flag to father of a deceased serviceman. permission of Zondervan Bible Chitra Barnabas, Jeanne James Publishers. ART Although the Seventh-day batant capacity—usually as Art and photo credits: Director, Byron Steele Adventist Church does not man- medics. To increase their effec- Cover, pp. 2, 3, 5 (bottom), 6, Designer, G. W. Busch date that its members not bear tiveness as they attempt to serve NSO; p. -

The Doctrine of Sin in the Thought of George R. Knight: Its Context and Implications

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Master's Theses Graduate Research 2009 The Doctrine of Sin in the Thought of George R. Knight: Its Context and Implications Jamie Kiley Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses Recommended Citation Kiley, Jamie, "The Doctrine of Sin in the Thought of George R. Knight: Its Context and Implications" (2009). Master's Theses. 47. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses/47 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT THE DOCTRINE OF SIN IN THE THOUGHT OF GEORGE R. KNIGHT: ITS CONTEXT AND IMPLICATIONS by Jamie Kiley Adviser: Denis Fortin ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Thesis Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE DOCTRINE OF SIN IN THE THOUGHT OF GEORGE R. KNIGHT: ITS CONTEXT AND IMPLICATIONS Name of researcher: Jamie Kiley Name and degree of faculty adviser: Denis Fortin, Ph.D. Date completed: December 2009 George R. Knight attempts to chart a middle course between various historical extremes on the doctrine of sin. His view of the Fall and of the consequent effects on human nature is not as pessimistic as that of theologians in the Augustinian tradition (including Martin Luther and John Calvin), who stress the complete corruption of human nature and the loss of free will. -

A Quarterly Publication of Adventist Chaplaincy Ministries

A QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF ADVENTIST CHAPLAINCY MINISTRIES ISSUE 4 2018 SEEKING HUMAN-TO-HUMAN RELATIONSHIPS PERSPECTIVE Terry Swenson, D.Min. Director of University Spiritual Care, Loma Linda University hen church members think The way we love and care for them is of Loma Linda University in the same way as Jesus did. Within W(LLU), many consider it and this verse, we discover that we can the surrounding locale as an Adventist love the world like Jesus did when Ghetto. As if everyone you meet there we see the world as Jesus did. How are Adventists. Reality is far different! we view others is how we will care Loma Linda’s student body represents for them. All too often, we make the 90 different countries, 60 faith groups, distinction between Adventist and and 69 different languages. We are non-Adventist. When we do this, our a microcosm of the world. Most very words reveal that we are placing students come from various Christian distinctions based on what we do and backgrounds with 50 percent of them believe as opposed to who we are. The being Seventh-day Adventist. How first categorizes and makes people does a team of Campus Chaplains care with differences the “other.” Which for their spiritual needs! inherently means they are not “us” nor LLU’s mission is “To continue the a “part of us.” teaching and healing ministry of Jesus Jesus viewed others differently. The Christ.” Therein lies the way to do Apostle Paul described it beautifully spiritual care and the power to do so in Galatians 3.