The President's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Btste St @Ennebßee

.¡:),i;-.it jrl*, l1ì1i*i{äj . ., ,.,::ì:;:i'_.¡..ll : r' btste st @enneBßee HOUSE RESOLUTION NO.5 By Representatives Matlock, Kevin Brooks, Hurley, Faison, Campbell, Dunn, Hill, Evans, Weaver, Rich A RESOLUTION to commemorate the 100th Anniversary of President Ronald Reagan's birth. WHEREAS, this General Assembly is proud to honor and commemorate the lives of those inspirational Americans who, throughout their estimable lives, committed themselves to public service of the highest order and whose outstanding contributions transformed our great nation and the world; and WHEREAS, one such distinguished public servant was President Ronald Reagan, a man who truly embodied the American spirit with his un-apologetic patriotism, undeniable magnetism, and unwavering belief in the American people, in their goodness and in their God- given ability and right to self-governance; and WHEREAS, born and raised in the Land of Lincoln, Ronald Wilson Reagan experienced a humble upbringing and acquired his legendary optimism and belief that individuals could determine their own destiny from his mother, Nelle Wilson Reagan, and his father, John Edward "Jack" Reagan; and WHEREAS, nicknamed "Dutch" by his father, Ronald Reagan was a natural born-leader, who served as captain of the swim team, student body president, and member of both the football team and Tau Kappa Epsilon fraternity while majoring in economics and sociology at Eureka College; and WHEREAS, pursuing his dream of a career in the entertainment industry, he became a radio sports.announcer on -

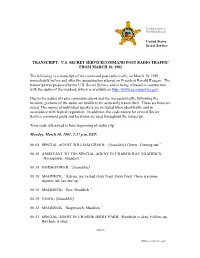

TRANSCRIPT: U.S. SECRET SERVICECOMMAND POST RADIO TRAFFIC from MARCH 30, 1981 the Following Is a Transcript of the Command Post

U.S Department of Homeland Security United States Secret Service TRANSCRIPT: U.S. SECRET SERVICECOMMAND POST RADIO TRAFFIC FROM MARCH 30, 1981 The following is a transcript of the command post radio traffic on March 30, 1981, immediately before and after the assassination attempt on President Ronald Reagan. The transcript was prepared by the U.S. Secret Service and is being released in conjunction with the audio of the incident, which is available on http://www.secretservice.gov. Due to the nature of radio communications and the increased traffic following the incident, portions of the audio are unable to be accurately transcribed. These sections are noted. The names of individual speakers are included when identifiable and in accordance with federal regulation. In addition, the code names for several Secret Service command posts and locations are used throughout the transcript. Time code referenced is from beginning of audio clip. Monday, March 30, 1981, 2:27 p.m. EST: 00:08 SPECIAL AGENT WILLIAM GREEN: “[Inaudible] Green. Coming out.” 00:16 ASSISTANT TO THE SPECIAL AGENT IN CHARGE RAY SHADDICK: “Horsepower, Shaddick.” 00:18 HORSEPOWER: “[inaudible]” 00:19 SHADDICK: “Advise, we’ve had shots fired. Shots fired. There are some injuries, uh, lay one on.” 00:26 SHADDICK: “Parr, Shaddick.” 00:29 VOICE: [Inaudible] 00:32 SHADDICK: “Stagecoach, Shaddick.” 00:35 SPECIAL AGENT IN CHARGE JERRY PARR: “Rawhide is okay, Follow-up. Rawhide is okay.” -more- www.secretservice.gov -2- 00:40 VOICE: [Inaudible] [OVERLAPPING} 00:41 SHADDICK: “Halfback, roger” 00:46 SHADDICK: “You wanna go to the hospital or back to the White House?” 00:50 PARR: “We’re going right… we’re going to Crown.” 00:52 SHADDICK: “Okay” 00:56 VOICE: [Inaudible] 00:58 SHADDICK: “Back to the White House. -

Grasso on Chervinsky

Lindsay M. Chervinsky. The Cabinet: George Washington and the Creation of an American Institution. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2020. 432 pp. $29.95, cloth, ISBN 978-0-674-98648-0. Reviewed by Joanne S. Grasso (New York Institute of Technology) Published on H-Early-America (July, 2021) Commissioned by Troy Bickham (Texas A&M University) As a grand epic but over a shorter period of jor author of the Federalist Papers. And Bradford history, Lindsay M. Chervinsky’s The Cabinet served in the Revolutionary War and then went chronicles George Washington and the creation of into law. The Virginia dynasty of presidents was in the first US presidential cabinet. In this expansive the making: Jefferson first served as secretary of account of how Washington oversaw, constructed, state, James Madison in the House of Representat‐ and ultimately organized his cabinet, the author ives, and James Monroe as an ambassador. segments her book from his pre-presidency days, In the introduction, the author begins her nar‐ when he developed relationships and strategies, in rative with the grandiose ceremony of the inaugur‐ the chapter “Forged in War,” to the initial stages of ation of Washington as the first president of the the development of his cabinet in “The Cabinet United States and then discusses many of his ad‐ Emerges,” and all the way through to problems in ministration’s initial tasks and strategies. Wash‐ “A Cabinet in Crisis.” ington used the “advice and consent” clause found As depicted, some of the brightest and time- in the United States Constitution with respect to tested minds from the Revolutionary War era were the US Senate, which states that the president cabinet members, including Henry Knox, Edmund “shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Randolph, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided and William Bradford. -

Reagan's Victory

Reagan’s ictory How HeV Built His Winning Coalition By Robert G. Morrison Foreword by William J. Bennett Reagan’s Victory: How He Built His Winning Coalition By Robert G. Morrison 1 FOREWORD By William J. Bennett Ronald Reagan always called me on my birthday. Even after he had left the White House, he continued to call me on my birthday. He called all his Cabinet members and close asso- ciates on their birthdays. I’ve never known another man in public life who did that. I could tell that Alzheimer’s had laid its firm grip on his mind when those calls stopped coming. The President would have agreed with the sign borne by hundreds of pro-life marchers each January 22nd: “Doesn’t Everyone Deserve a Birth Day?” Reagan’s pro-life convic- tions were an integral part of who he was. All of us who served him knew that. Many of my colleagues in the Reagan administration were pro-choice. Reagan never treat- ed any of his team with less than full respect and full loyalty for that. But as for the Reagan administration, it was a pro-life administration. I was the second choice of Reagan’s to head the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). It was my first appointment in a Republican administration. I was a Democrat. Reagan had chosen me after a well-known Southern historian and literary critic hurt his candidacy by criticizing Abraham Lincoln. My appointment became controversial within the Reagan ranks because the Gipper was highly popular in the South, where residual animosities toward Lincoln could still be found. -

Brady, James S.: Files

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF of a folder from our textual collections. Collection: Brady, James S.: Files Folder Title: [Press Conferences and Press Releases – Assassination Attempt] (3 of 3) Box: OA 16783 To see more digitized collections visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digital-library To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/document-collection Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/citing THE WHITE HOUSE Office of the Press Secretary March 31, 1981 NOTICE TO THE PRESS At 6:15 this morning, the President left. the recovery room for the intensive care ward. Dr. Daniel Ruge, the President's personal physician, said, "The President's vital signs are all in the normal range. He's in exceptionally good condition." Dr. Ruge indicated that the President was talking and writing notes. On James Brady's condition, Dr. Ruge said, "It is serious, but improving. It's too early to make a prognosis. He is somewhat responsive." Dr. Ruge also said that Secret Service agent Time.thy McCarthy's condition is "very fine." Doctors at the Washington Hospital Center said the condition of D.C. policeman Thomas Delahanty is serious, but the prognosis is good. At 5:30 this morning, Michael Reagan, Maureen Reagan, and Patti Davis arrived. at the White House. Ron Reagan and his wife, Doria, arrived last night. All of the children will be staying at the White House.· ##t THE WHITE HOUSE Off ice of the Press Secretary MARCH 31, 1981 NOTICE TO THE PRESS Dr. -

The New Age Under Orage

THE NEW AGE UNDER ORAGE CHAPTERS IN ENGLISH CULTURAL HISTORY by WALLACE MARTIN MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS BARNES & NOBLE, INC., NEW YORK Frontispiece A. R. ORAGE © 1967 Wallace Martin All rights reserved MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS 316-324 Oxford Road, Manchester 13, England U.S.A. BARNES & NOBLE, INC. 105 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10003 Printed in Great Britain by Butler & Tanner Ltd, Frome and London This digital edition has been produced by the Modernist Journals Project with the permission of Wallace T. Martin, granted on 28 July 1999. Users may download and reproduce any of these pages, provided that proper credit is given the author and the Project. FOR MY PARENTS CONTENTS PART ONE. ORIGINS Page I. Introduction: The New Age and its Contemporaries 1 II. The Purchase of The New Age 17 III. Orage’s Editorial Methods 32 PART TWO. ‘THE NEW AGE’, 1908-1910: LITERARY REALISM AND THE SOCIAL REVOLUTION IV. The ‘New Drama’ 61 V. The Realistic Novel 81 VI. The Rejection of Realism 108 PART THREE. 1911-1914: NEW DIRECTIONS VII. Contributors and Contents 120 VIII. The Cultural Awakening 128 IX. The Origins of Imagism 145 X. Other Movements 182 PART FOUR. 1915-1918: THE SEARCH FOR VALUES XI. Guild Socialism 193 XII. A Conservative Philosophy 212 XIII. Orage’s Literary Criticism 235 PART FIVE. 1919-1922: SOCIAL CREDIT AND MYSTICISM XIV. The Economic Crisis 266 XV. Orage’s Religious Quest 284 Appendix: Contributors to The New Age 295 Index 297 vii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS A. R. Orage Frontispiece 1 * Tom Titt: Mr G. Bernard Shaw 25 2 * Tom Titt: Mr G. -

The Rhetoric of the Benign Scapegoat: President Reagan and the Federal Government

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2000 The Rhetoric of the Benign Scapegoat: President Reagan and the Federal Government. Stephen Wayne Braden Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Braden, Stephen Wayne, "The Rhetoric of the Benign Scapegoat: President Reagan and the Federal Government." (2000). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7340. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7340 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Good Books About History, 2015-16 Bernard Bailyn, the Barbarous

Good Books about History, 2015-16 Reviews by members of the OLLI-GMU History Club Compiled by Tom Hady Compiler’s Note: With our decision a few years ago to include historical fiction, the question of what to call “history” has become more difficult. I view my role as limited. I will occasionally ask a contributor whether this belongs in a history compilation, but I generally accept their conclusion. Other than that, I compile the reviews, put them in a common format, and do a very limited amount of editing.--TFH. Bernard Bailyn, The Barbarous Years; The Peopling of British North America—The Conflict of Civilizations, 1600-1675 (2013), reviewed by Jim Crumley In this book, Mr. Bailyn takes a look at the early settlers in America, focusing on the colonization of Virginia, Massachusetts, and New York, though he also discusses the early years of the Maryland and Delaware colonies. Even someone steeped in Virginia history and very familiar with the Jamestown colony will find new information in this book. It’s a somewhat ponderous volume and not read quickly or easily, but it’s packed with information, including statistics on the extraordinarily high mortality rates among the colonists. Marina Belozerskaya, To Wake the Dead: A Renaissance Merchant and the Birth of Archaeology (2009), reviewed by Tom Hady In 1407, fourteen-year-old Ciriacus Pizzecolii or Ancona was apprenticed to learn the trade of a merchant. As a merchant, he travelled widely in the Mediterranean, and he became interested in the ancient ruins that lay all over that part of the world. -

Markarian Final Paper, 9/14/11

Amy Markarian Final Paper, 9/14/11 Teaching American History A More Perfect Union: The Origins & Development of the U.S. Constitution Book Review: Rawhide Down: The Near Assassination of Ronald Reagan by Del Quentin Wilber I currently teach “Ancient Civilizations” at the middle school level. Therefore, when given the opportunity to choose a book to review that either assists my teaching or increases my content knowledge, it was an obvious choice for me to select something that will increase my general content knowledge (with the hope that it will someday assist my teaching). I am a child of the eighties, and Ronald Reagan is the first President I remember…vaguely. As we discussed this man and his Presidency in our class, I found myself remembering my childhood interpretations of his personal qualities and events that took place. I was fascinated to learn more about how those interpretations and memories compare with the more experienced perspectives of adults and historians who also remember this time. With the idea that the book that I chose would someday serve to shape my teaching of this President, I sought one that would provide me with an accurate historical perspective, but that would also somehow “personalize” the information in a way that makes it accessible and interesting to students. In much the same way that Frederick Lewis Allen’s, Only Yesterday, offers a detailed, microscopic view of life in the 1920s, Del Quentin Wilber’s, Rawhide Down, offers an intricate perspective of Ronald Reagan and those surrounding him on one particular day of his life. -

Linguistic Scepticism in Mauthner's Philosophy

LiberaPisano Misunderstanding Metaphors: Linguistic ScepticisminMauthner’s Philosophy Nous sommes tous dans un désert. Personne ne comprend personne. Gustave Flaubert¹ This essayisanoverview of Fritz Mauthner’slinguistic scepticism, which, in my view, represents apowerful hermeneutic category of philosophical doubts about the com- municative,epistemological, and ontological value of language. In order to shed light on the main features of Mauthner’sthought, Idrawattention to his long-stand- ing dialogue with both the sceptical tradition and philosophyoflanguage. This con- tribution has nine short sections: the first has an introductory function and illus- tratesseveral aspectsoflinguistic scepticism in the history of philosophy; the second offers acontextualisation of Mauthner’sphilosophyoflanguage; the remain- der present abroad examination of the main features of Mauthner’sthought as fol- lows: the impossibility of knowledge that stems from aradicalisationofempiricism; the coincidencebetween wordand thought,thinkingand speaking;the notion of use, the relevanceoflinguistic habits,and the utopia of communication; the decep- tive metaphors at the root of an epoché of meaning;the new task of philosophyasan exercise of liberation against the limits of language; the controversial relationship between Judaism and scepticism; and the mystical silence as an extreme conse- quence of his thought.² Mauthnerturns scepticism into aform of life and philosophy into acritique of language, and he inauguratesanew approach that is traceable in manyGerman—Jewish -

John Marshall

William & Mary Law Review Volume 43 (2001-2002) Issue 4 Symposium: The Legacy of Chief Article 9 Justice John Marshall March 2002 John Marshall: Remarks of October 6, 2000 William H. Rehnquist Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Legal History Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Repository Citation William H. Rehnquist, John Marshall: Remarks of October 6, 2000, 43 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 1549 (2002), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol43/iss4/9 Copyright c 2002 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr JOHN MARSHALL REMARKS OF OCTOBER 6,2000 WILLIAM H. REHNQUIST* Thank you, Dean Reveley, for the kind introduction. It is a great pleasure to be here. Next January will be the two hundredth anniversary of the appointment of John Marshall as Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. I am quite convinced that Marshall deserves to be recognized along with George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and Thomas Jefferson as one of the "Founding Fathers" of this country. Admittedly, he does not have the name recognition of Washington, Hamilton, or Jefferson, but a strong case can be made for the proposition that his contribution to our system of government ranks with any of theirs. I shall try to make that case this evening. Of these Founders, Washington had the experience as a military commander and the reputation for public rectitude that were essential in our first President. -

Rawhide Down: the Near Assassination of President Reagan

Journal of Strategic Security Volume 5 Number 1 Volume 5, No. 1: Spring 2012 Article 3 Rawhide Down: The Near Assassination of President Reagan. By Del Quentin Wilber (New York, NY, Henry Holt and Company, 2011) J. Branch Walton Henley-Putnam University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss pp. 93-94 Recommended Citation Walton, J. Branch. "Rawhide Down: The Near Assassination of President Reagan. By Del Quentin Wilber (New York, NY, Henry Holt and Company, 2011)." Journal of Strategic Security 5, no. 1 (2012) : 93-94. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.5.1.8 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/vol5/iss1/3 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Strategic Security by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rawhide Down: The Near Assassination of President Reagan. By Del Quentin Wilber (New York, NY, Henry Holt and Company, 2011) This book review is available in Journal of Strategic Security: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/ vol5/iss1/3 Walton: Rawhide Down: The Near Assassination of President Reagan. By Del Rawhide Down: The Near Assassination of President Reagan. By Del Quentin Wilber. New York, NY, Henry Holt and Company, 2011. ISBN: 978-08050-9346-9. Photographs. Notes. Bibliography. Pp 305. $27.00 Del Quentin Wilber, a biographer of President Ronald Reagan, has writ- ten a detailed narrative of the attempt to assassinate him on March 30, 1981, as he walked out of the Washington Hilton Hotel in Washington, D.C.