Transcripts and Video from the 2018 Communities in Control Conference and from Previous Years, Visit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Re-Awakening Languages: Theory and Practice in the Revitalisation Of

RE-AWAKENING LANGUAGES Theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages Edited by John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch and Michael Walsh Copyright Published 2010 by Sydney University Press SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS University of Sydney Library sydney.edu.au/sup © John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch & Michael Walsh 2010 © Individual contributors 2010 © Sydney University Press 2010 Reproduction and Communication for other purposes Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University Press at the address below: Sydney University Press Fisher Library F03 University of Sydney NSW 2006 AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] Readers are advised that protocols can exist in Indigenous Australian communities against speaking names and displaying images of the deceased. Please check with local Indigenous Elders before using this publication in their communities. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Re-awakening languages: theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages / edited by John Hobson … [et al.] ISBN: 9781920899554 (pbk.) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Aboriginal Australians--Languages--Revival. Australian languages--Social aspects. Language obsolescence--Australia. Language revival--Australia. iv Copyright Language planning--Australia. Other Authors/Contributors: Hobson, John Robert, 1958- Lowe, Kevin Connolly, 1952- Poetsch, Susan Patricia, 1966- Walsh, Michael James, 1948- Dewey Number: 499.15 Cover image: ‘Wiradjuri Water Symbols 1’, drawing by Lynette Riley. Water symbols represent a foundation requirement for all to be sustainable in their environment. -

7. Kristie LU STOUT – CNN INTERNATIONAL

Bio & Policy Statement from A Nominee for Correspondent Member Governor 7 Board of Governors 2021-2022 Kristie LU STOUT Affiliation: CNN INTERNATIONAL POLICY STATEMENT I am honored to be nominated again as a Correspondent Governor of the Foreign Correspondents' Club, a thriving social center and world-renowned press club. Over the last year, I have served as a co-convener of the Wall Committee, helping to bring a series of powerful exhibits to the Club’s Van Es Wall including a selection of iconic photographs of the violent insurrection and historic inauguration in America. The committee is also proud to showcase an exhibit of images by the brave photojournalists of Frontier Myanmar who are chronicling the bold protests and brutal crackdown inside the country. As a Correspondent Governor, I have also served as an active member of the Professional Committee, helping to organize a number of speaking events for the Club including panel discussions on topics ranging from the coronavirus pandemic to anti-Asian violence in America, as well as in-depth conversations with authors including Sichuan culinary expert Fuchsia Dunlop and award-winning journalist Stan Grant. Previously, as a proud member of the club, I have been involved as a moderator, speaker, and panelist for numerous FCC panels and Journalism Day conferences. I have had the opportunity to share my views on digital transformation, misinformation, and gender equality, while speaking alongside my respected peers on how we have covered major events in the region. If again elected to the board, I would continue to contribute to the already powerful line-up of FCC exhibits and events that inform journalists and educate the greater community. -

Developing Identity As a Light-Skinned Aboriginal Person with Little Or No

Developing identity as a light-skinned Aboriginal person with little or no community and/or kinship ties. Bindi Bennett Bachelor Social Work Faculty of Health Sciences Australian Catholic University A thesis submitted to the ACU in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy 2015 1 Originality statement This thesis contains no material published elsewhere (except as detailed below) or extracted in whole or part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No parts of this thesis have been submitted towards the award of any other degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgment in the main text of the thesis. All research procedures reported in the thesis received the approval of the relevant Ethics Committees. This thesis was edited by Bruderlin MacLean Publishing Services. Chapter 2 was published during candidature as Chapter 1 of the following book Our voices : Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social work / edited by Bindi Bennett, Sue Green, Stephanie Gilbert, Dawn Bessarab.South Yarra, Vic. : Palgrave Macmillan 2013. Some material from chapter 8 was published during candidature as the following article Bennett, B.2014. How do light skinned Aboriginal Australians experience racism? Implications for Social Work. Alternative. V10 (2). 2 Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................... -

1-3 April 2016 Festival Program 2 Newcastle Writers Festival 1-3 April 2016

1-3 April 2016 Festival Program 2 Newcastle Writers Festival 1-3 April 2016 Ticket Information Transport Information The Newcastle Writers Festival is The festival is held in the Civic Precinct, which is close to bus links and the bustling Honeysuckle and committed to providing free sessions Darby Street eatery strips. in its program. Tickets are not needed Please note, the rail line has been cut at Hamilton Station and passengers cannot alight at Civic or for these events. Seats are offered on Newcastle stations. Buses are available at Hamilton Station for transfers to the city. For updates a “first in, first served” basis. Admission about track work and for timetable information see www.sydneytrains.info. cannot be guaranteed for free events. For bus timetables see www.newcastlebuses.info. All other tickets are available from Ticketek and can be bought over the Newcastle Taxis bookings can be made by phoning 133 300 or book online at counter, online at www.ticketek.com www.newcastletaxis.com.au. or by contacting the box office on You are encouraged to leave your car at home, especially on Saturday, 2 April, as community markets (02) 4929 1977. Please note, the will be held in Civic Park and parking spaces will be hard to secure. The festival recommends all-day advertised ticket price includes parking at the Wilson Parking station on the corner of Perkins and King streets, Newcastle. For more Ticketek’s service fee but unless you details see www.huntercarparks.com.au and www.wilsonparking.com.au. buy your tickets over the counter, the sale will incur an additional delivery fee. -

Divisions & Derisions

DIVISIONS & DERISIONS WHEN PREJUDICE PREVAILS Join us for a riveting panel discussion about social inclusion in Australia. Are we as a nation able to celebrate diversity in all of its forms? Can we rise above prejudices based on religion, gender, colour or creed? Wednesday 15 June at 6:30pm The Sydney Jewish Museum Catherine McGregor AM Stan Grant Diversity Champion Journalist Catherine McGregor is a writer Stan has been a journalist for a commentator, broadcaster and quarter of a century. He has been an Queensland Australian of The Year for ABC Federal Political Correspondent, 2016. She served for nearly four decades London based European Correspondent in the Australian Defence Force and was for the Seven Network and China gazetted in the MIlitary Division of the Correspondent for CNN. He is a Order of Australia on Australia Day 2012. member of the Wiradjuri and Kamiaroi Catherine’s personal story of gender Aboriginal people. In 2011 he published transition is compelling and inspiring. his book ‘The Tears of Strangers’. Widyan Fares Vic Alhadeff Senior Writer - Point Magazine, Chief Executive Officer NSW Multicultural NSW Jewish Board of Deputies Widyan has worked as a reporter for Vic is the former Chair of the NSW Network Ten’s Late News Team and Community Relations Commission, was the host of SBS PopAraby. In former editor of the Australian Jewish 2014, she was one of three people News and former chief sub-editor of offered the SBS Journalism The Cape Times in South Africa. He cadet-ship, making her one of the is the author of two books on South first veiled TV reporters on Australian African history. -

The Book Thief

Ryde Library Service Community Book Club Collection Talking to my country By Stan Grant First published in 2016 Genre & subject Aboriginal Australians Racism Reconciliation Synopsis An extraordinarily powerful and personal meditation on race, culture and national identity. In July 2015, as the debate over Adam Goodes being booed at AFL games raged and got ever more heated and ugly, Stan Grant wrote a short but powerful piece for The Guardian that went viral, not only in Australia but right around the world, shared over 100,000 times on social media. His was a personal, passionate and powerful response to racism in Australia and the sorrow, shame, anger and hardship of being an indigenous man. 'We are the detritus of the brutality of the Australian frontier', he wrote, 'We remained a reminder of what was lost, what was taken, what was destroyed to scaffold the building of this nation's prosperity.' Stan Grant was lucky enough to find an escape route, making his way through education to become one of our leading journalists. He also spent many years outside Australia, working in Asia, the Middle East, Europe and Africa, a time that liberated him and gave him a unique perspective on Australia. This is his very personal meditation on what it means to be Australian, what it means to be indigenous, and what racism really means in this country. Talking to My Country is that rare and special book that talks to every Australian about their country - what it is, and what it could be. It is not just about race, or about indigenous people but all of us, our shared identity. -

GATEWAY GENEROUS DONORS RECOGNISED Letter to the Editor ‘Your Article on Food at Trinity Reminded Me of How Syd Wynne’S Kitchen Prepared Me for Life in India

No 85 November 2016 The Magazine of Trinity College, The University of Melbourne GATEWAY GENEROUS DONORS RECOGNISED Letter to the Editor ‘Your article on food at Trinity reminded me of how Syd Wynne’s kitchen prepared me for life in India. In 1964 I was the most junior tutor, the one whose duty it was to grind the SCR coffee beans. One night I had occasion to visit the kitchen, so I opened the door, turned on the light and watched as the place became alive with little black oblong shapes scuttling for the nearest shade. The following year I became a lecturer at Madras Christian College, with a flat to live in complete with a small kitchen and my very own cook/bearer. This kitchen, too, was alive with cockroaches, but thanks to Trinity caused me no discomfort, as I was already familiar with harmless kitchen wildlife.’ Ian Manning (TC 1963) We would love to hear what you think. Email the Editor at [email protected] Don Grilli, Chef Extraordinaire, 1962 JOIN YOUR NETWORK Trinity has over 23,000 alumni in more than 50 countries. This global network puts you in touch with lawyers, doctors, consultants, engineers, musicians, theologians, architects and many more. You Founded in 1872 as the first college of the University of can organise work experience for students, internships or act as a Melbourne, Trinity College is a unique tertiary institution mentor for students or young alumni. Expand your business contacts that provides a diverse range of rigorous academic programs via our LinkedIn group. -

Sydney Writers' Festival

Bibliotherapy LET’S TALK WRITING 16-22 May 1HERSA1 S001 2 swf.org.au SYDNEY WRITERS’ FESTIVAL GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES SUPPORTERS Adelaide Writers’ Week THE FOLLOWING PARTNERS AND SUPPORTERS Affirm Press NSW Writers’ Centre Auckland Writers & Readers Festival Pan Macmillan Australia Australian Poetry Ltd Penguin Random House Australia The Australian Taxpayers’ Alliance Perth Writers Festival CORE FUNDERS Black Inc. Riverside Theatres Bloomsbury Publishing Scribe Publications Brisbane Powerhouse Shanghai Writers’ Association Brisbane Writers Festival Simmer on the Bay Byron Bay Writers’ Festival Simon & Schuster Casula Powerhouse Arts Centre State Library of NSW Créative France The Stella Prize Griffith REVIEW Sydney Dance Lounge Harcourts International Conference Text Publishing Hardie Grant Books University of Queensland Press MAJOR PARTNERS Hardie Grant Egmont Varuna, the National Writers’ House HarperCollins Publishers Walker Books Hachette Australia The Walkley Foundation History Council of New South Wales Wheeler Centre Kinderling Kids Radio Woollahra Library and Melbourne University Press Information Service Musica Viva Word Travels PLATINUM PATRON Susan Abrahams The Russell Mills Foundation Rowena Danziger AM & Ken Coles AM Margie Seale & David Hardy Dr Kathryn Lovric & Dr Roger Allan Kathy & Greg Shand Danita Lowes & David Fite WeirAnderson Foundation GOLD PATRON Alan & Sue Cameron Adam & Vicki Liberman Sally Cousens & John Stuckey Robyn Martin-Weber Marion Dixon Stephen, Margie & Xavier Morris Catherine & Whitney Drayton Ruth Ritchie Lisa & Danny Goldberg Emile & Caroline Sherman Andrea Govaert & Wik Farwerck Deena Shiff & James Gillespie Mrs Megan Grace & Brighton Grace Thea Whitnall PARTNERS The Key Foundation SILVER PATRON Alexa Haslingden David Marr & Sebastian Tesoriero RESEARCH & ENGAGEMENT Susan & Jeffrey Hauser Lawrence & Sylvia Myers Tony & Louise Leibowitz Nina Walton & Zeb Rice PATRON Lucinda Aboud Ariane & David Fuchs Annabelle Bennett Lena Nahlous James Bennett Pty Ltd Nicola Sepel Lucy & Stephen Chipkin Eva Shand The Dunkel Family Dr Evan R. -

Special Issue

ethical space The International Journal of Communication Ethics Vol.15 Nos.3/4 2018 ISSN 1742-0105 Special Issue: The ethics of the journalistic memoir: Radical departures Edited by Sue Joseph PAPERS • Lara Pawson’s genre-bending memoir – gravitas and the celebration of unique cultural spaces – by Richard Lance Keeble • When journalism isn’t enough: ‘Horror surrealism’ in Behrouz Boochani’s testimonial prison narrative – by Willa McDonald • On being unfair: The ethics of the memoir-journalism hybrid – by Lisa A. Phillips • Stan Grant and cultural memory: Embodying a national race narrative through memoir – by Sue Joseph PLUS • Liberal mass media and the ‘Israel lobby’ theory – by T. J. Coles • Media trust and use among urban news consumers in Brazil – by Flávia Milhorance and Jane Singer • Balancing instrumental rationality and value rationality in communicating information: A study of the ‘Nobel Older Brother’ case – by Lili Ning www.abramis.co.uk abramis • Dumbs gone to Iceland: (Re)presentations of English national identity during Euro 2016 and the EU referendum – by Roger Domeneghetti • ‘An eye in the eye of the hurricane’: Fire and fury, immersion and ethics in political literary journalism – by Kerrie Davies abramis academic • The science communication challenge: Truth and disagreement www.abramis.co.uk in democratic knowledge societies – by Gitte Meyer Publishing Office Aims and scope Abramis Academic ASK House Communication ethics is a discipline that supports communication Northgate Avenue practitioners by offering tools and analyses for the understanding of Bury St. Edmunds ethical issues. Moreover, the speed of change in the dynamic information Suffolk environment presents new challenges, especially for communication IP32 6BB practitioners. -

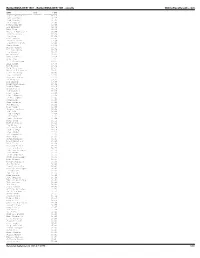

Bolderboulder 10K Results

BolderBOULDER 1987 - BolderBOULDER 10K - results OnlineRaceResults.com NAME DIV TIME ---------------------- ------- ----------- Ronnie Archuleta 31:11 Jeff Sanchez 31:35 Todd Wienke 31:50 Erin Vedeler 32:00 Nathan Wright 32:09 Bob Mcanany 32:32 Rick Katz 32:36 Michael Kubitschek 32:49 Timothy Jones 32:54 Don Hume 32:59 Pick Renfrow 33:03 David Kissner 33:06 Robert Hillgrove 33:08 James Houge 33:11 Marcus Canipe 33:15 Keith Golding 33:19 Ken Masarie 33:21 Quinn Smith 33:23 Alex Accetta 33:25 Andy Ames 33:27 D. K Corrallass 33:27 Bill Clark 33:30 Bob Boland 33:32 Erid Morrison 33:35 Michael Velascuez 33:37 Lance Denning 33:40 Bret Rickard 33:41 Charles Lusman 33:43 Brian Grier 33:44 Ron Harmon 33:46 Randy Liljenberg 33:49 Daniel King 33:51 Chuck Dooley 33:53 Ted Macblane 33:55 Nick Laydon 33:56 Finn Esbensew 33:58 Brian Jordan 34:00 David Lowe 34:00 Stan Allison 34:00 Job Hermens 34:01 Paul Duppen 34:03 Thomas Donohoue 34:04 Bob Fink 34:04 Bobb Finegan 34:05 Jim Tanner 34:07 Bruce Polford 34:09 Wayne Roth 34:11 Matt Peterson 34:13 Don Bieber 34:15 Dale Garland 34:16 Dave Dooley 34:18 Klye Hubbart 34:20 Kit Carpenter 34:21 Mati Maske 34:22 Kevin Macblane 34:24 Raley Hinojosa 34:26 Bill Kelly 34:28 Richard Kinney 34:30 Dave Leathers 34:31 John Des Roaiers 34:32 Ross Adams 34:32 Erick Anderson 34:33 Steve Rischeling 34:34 Pete Ybarra 34:37 Robert Anderson 34:40 Jay Kirksey 34:40 Daniel Corrales 34:42 Patrick Carringan 34:42 Dariub Baer 34:44 Dan Tomlin 34:45 Paul Fuller 34:46 Dave Swanson 34:46 Vincent Lostetier 34:47 Mike Sprung 34:48 Tom -

Strengthening Relationships and Cultivating Strategic Thinking Across

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 STRENGTHENING RELATIONSHIPS AND CULTIVATING STRATEGIC THINKING ACROSS THE INDO - PACIFIC AND THE UNITED STATES OUR VISION The vision of the Perth USAsia Centre is to become an influential institution recognised in Australia, across the Indo-Pacific region and the United States as contributing significantly to strategic thinking, policy development and strengthening relationships across a dynamic region. OUR HISTORY OUR MISSION Under the leadership of the Australian and Western Australian The Perth USAsia Centre is a Governments and the American Australian Association (AAA), non-partisan, not-for-profit the Perth USAsia Centre was an initiative built on the successes institution that promotes of the United States Studies Centre at the University of Sydney stronger relationships between (USSC), to develop a USSC related presence on the nation’s West Coast in response to the growing strategic importance of Western Australia, the Indo - Pacific and the United States by Australia in the Indo-Pacific region. contributing to strategic On 13 November 2012, US Secretary of State, Hillary Rodham thinking, policy development Clinton, launched the Perth USAsia Centre, as a globally significant and enhanced networks research institution and leading think-tank on the Australia- between government, Asia-US strategic and economic relationship. Being located the private sector and at The University of Western Australia (UWA), the Centre is academia. The Perth USAsia uniquely positioned to serve as a world class research and policy Centre is also a conduit for development hub encouraging a deeper Australian understanding greater communication and of business, culture, history, politics and foreign policy in the Indo- understanding across the Pacific and the US. -

The Australian Dream in Cinemas August 22

THE AUSTRALIAN DREAM IN CINEMAS AUGUST 22 DIRECTED BY DANIEL GORDON RUNNING TIME 106 MINS RATED TBC MADMAN ENTERTAINMENT PUBLICITY CONTACTS: CAROLINE WHITEWAY – [email protected] https://www.madmanfilms.com.au/the-australian-dream/ #AustralianDream FACEBOOK | INSTAGRAM | TWITTER The producers acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the sovereign lands where this documentary was filmed. LOGLINE: When the truth of history is told, we can all walk together. SHORT SYNOPSIS The Australian Dream is a documentary that uses the remarkable and inspirational story of Indigenous AFL legend Adam Goodes as the prism through which to tell a deep and powerful story about race, identity and belonging. For the first time Adam reveals his profoundly emotional journey in his own words and asks fundamental questions about the nature of racism and discrimination in society today. Walkley award- winning writer Stan Grant and BAFTA award-winning director Daniel Gordon join forces to tell this remarkable story of one of the most decorated & celebrated players in AFL history. A man who remains a cultural hero; the very epitome of resilience & survival, who continues to fight for equality and reconciliation. SYNOPSIS From shy country kid to two-time Brownlow medallist and Australian of the Year, Goodes is an inspiration to many. The footy field was where he thrived; the only place where the colour of his skin was irrelevant. Goodes’ world fell apart when he became the target of racial abuse during a game, which spiralled into public backlash against him. He spoke out about racism when Australia was not ready to hear the ugly truth, retiring quietly from AFL heartbroken.