Cutbank 84 Article 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ten Minutes to Midnight Fringe Festival 2015 Award Winning Artists Teresa Luke Linda Jessie

Ten Minutes to Midnight Fringe Festival 2015 Award Winning Artists Teresa Luke Linda Jessie Creative Team Teresa Crea (Dramaturgy and Conceptual Development)- leading Australian writer and director with a background in social and community engagement. Teresa trained in film and theatre, and co-founded Australia’s first professionally recognised bicultural performance company, Doppio Teatro, receiving national awards for seminal contribution to multiculturalism in the arts. Teresa was awarded a New Media Arts Fellowship in 2003 and has recently completed a doctorate investigating narrative in immersive and simulated environments. Luke Harrald – composer, performer and new-media artist known for his groundbreaking work with improvisation and interactive computer music. Originally from the mid-north of SA, Luke is currently the head of studies for the Popular Music and Creative Technologies program at the University of Adelaide, and lectures in Sonic Arts. He has performed internationally (in London, Paris and Montreal) and is an important contributor to the Adelaide art music scene. Nic Mollison – stage lighting & projection designer since graduating from the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts (WAAPA) in 1995. Nic has worked with diverse range of theatre, dance & youth arts companies on local, national & international productions, including lighting & video projections for concerts, festivals, nightclubs & visual art installations. He has lectured in lighting & Projection at the University of SA and The Adelaide College Of the Arts. John Romeril - leading Australian playwright (plays include The Floating World, Carboni, The Kelly Dance, Miss Tanaka and Jack Charles versus the Crown). John has been Playwright-in-Residence for many communities, theatre companies and tertiary institutions. -

The Normal Heart

THE NORMAL HEART Written By Larry Kramer Final Shooting Script RYAN MURPHY TELEVISION © 2013 Home Box Office, Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No portion of this script may be performed, published, reproduced, sold or distributed by any means or quoted or published in any medium, including on any website, without the prior written consent of Home Box Office. Distribution or disclosure of this material to unauthorized persons is prohibited. Disposal of this script copy does not alter any of the restrictions previously set forth. 1 EXT. APPROACHING FIRE ISLAND PINES. DAY 1 Masses of beautiful men come towards the camera. The dock is full and the boat is packed as it disgorges more beautiful young men. NED WEEKS, 40, with his dog Sam, prepares to disembark. He suddenly puts down his bag and pulls off his shirt. He wears a tank-top. 2 EXT. HARBOR AT FIRE ISLAND PINES. DAY 2 Ned is the last to disembark. Sam pulls him forward to the crowd of waiting men, now coming even closer. Ned suddenly puts down his bag and puts his shirt back on. CRAIG, 20s and endearing, greets him; they hug. NED How you doing, pumpkin? CRAIG We're doing great. 3 EXT. BRUCE NILES'S HOUSE. FIRE ISLAND PINES. DAY 3 TIGHT on a razor shaving a chiseled chest. Two HANDSOME guys in their 20s -- NICK and NINO -- are on the deck by a pool, shaving their pecs. They are taking this very seriously. Ned and Craig walk up, observe this. Craig laughs. CRAIG What are you guys doing? NINO Hairy is out. -

Fringe Benefits County of Los Angeles Memorandum of Understanding

SEIU Local 721 Fringe Benefits County of Los Angeles Memorandum of Understanding October 1, 2015, through September 30, 2018 721 FB MAS AMENDMENT NO. I MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING FOR JOINT SUBMISSION TO BOARD OF SUPERVISORS REGARDING THE FRINGE BENEFIT AGREEMENT THIS AMENDMENT NO. I TO THE MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING, made and entered into this j6th day of August, 2016; BY AND BETWEEN Authorized Management Representatives (hereinafter referred to as “Management”) of the County of Los Angeles (hereinafter referred to as County”) AND LOS ANGELES COUNTY EMPLOYEES ASSOCIATION, SEIU, LOCAL 721, CTW, CLC (hereinafter referred to as “UnionTM) WHEREAS, on the 1st day of October2015, the parties entered into a Memorandum of Understanding regarding the Fringe Benefits, which Memorandum of Understanding was subsequently approved and ordered implemented by the County’s Board of Supervisors: and 721 FB MAS WHEREAS, as a result of mutual agreement, the parties desire to amend the MOU Article as set forth hereafter: NOW, THEREFORE, the parties agree as follows: 1. Amend Article 27 — Commuting Problems, Paragraph 5 — The County will advance to the Green@Work Joint Labor Management Committee, as follows: MOU Term Year 201 5-2016 $200,000 August 2016 $ 25,000 (one-time gap funding) September 2016 $ 25,000 (one-time gap funding) MOU Term Year 2016-2017 $200,000 MOU Term Year 2017-2018 $200,000 These funds shall be used for the specific purpose of maximizing direct financial rideshare subsidies for employees, and enhancing alternative transportation systems, such as shuttle services, van pools, car pools, bicycle parking, other transit services and guaranteed tide home services. -

''What Lips These Lips Have Kissed'': Refiguring the Politics of Queer Public Kissing

Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies Vol. 3, No. 1, March 2006, pp. 1Á/26 ‘‘What Lips These Lips Have Kissed’’: Refiguring the Politics of Queer Public Kissing Charles E. Morris III & John M. Sloop In this essay, we argue that man-on-man kissing, and its representations, have been insufficiently mobilized within apolitical, incremental, and assimilationist pro-gay logics of visibility. In response, we call for a perspective that understands man-on-man kissing as a political imperative and kairotic. After a critical analysis of man-on-man kissing’s relation to such politics, we discuss how it can be utilized as a juggernaut in a broader project of queer world making, and investigate ideological, political, and economic barriers to the creation of this queer kissing ‘‘visual mass.’’ We conclude with relevant implications regarding same-sex kissing and the politics of visible pleasure. Keywords: Same-Sex Kissing; Queer Politics; Public Sex; Gay Representation In general, one may pronounce kissing dangerous. A spark of fire has often been struck out of the collision of lips that has blown up the whole magazine of 1 virtue.*/Anonymous, 1803 Kissing, in certain figurations, has lost none of its hot promise since our epigraph was penned two centuries ago. Its ongoing transformative combustion may be witnessed in two extraordinarily divergent perspectives on its cultural representation and political implications. In 2001, queer filmmaker Bruce LaBruce offered in Toronto’s Eye Weekly a noteworthy rave of the sophomoric buddy film Dude, Where’s My Car? One scene in particular inspired LaBruce, in which we find our stoned protagonists Jesse (Ashton Kutcher) and Chester (Seann William Scott) idling at a stoplight next to superhunk Fabio and his equally alluring female passenger. -

2019 City Enrichment Fund SUMMARY

Appendix A to Report GRA19002 2019 City Enrichment Fund SUMMARY No. of 2019 Budget 2019 Category Apps (Total) 2019 Requested Recommended Budget vs Recommended Community Services CS - A Hunger/Shelter 10 $ 416,324 $ 360,015 CS - B Everyone Safe 9 $ 294,291 $ 286,846 CS - C Everyone Thrives 9 $ 299,588 $ 268,321 CS - D No Youth Left Behind 7 $ 180,209 $ 159,608 CS - E Everyone Age in Place 20 $ 485,352 $ 455,101 CS - F Community Capacity Grows 11 $ 214,373 $ 189,492 CS - G Someone to Talk to 7 $ 247,728 $ 141,317 CS - H Emerging Needs 22 $ 553,916 $ 303,660 Community Services Total 95 $ 2,164,360 $ 2,691,781 $ 2,164,360 $ - 0.00% Agriculture AGR A Programs and Events 18 $ 178,615 $ 130,841 Agriculture Total 18 $ 143,361 $ 178,615 $ 130,841 $ 12,520 8.73% Arts ART - A Arts - Operating 34 $ 3,977,467 $ 2,436,164 ART - B Arts - Festival 10 $ 300,070 $ 179,486 ART - C Arts - Capacity Building 9 $ 113,000 $ 58,597 ART - D Arts - Creation & Presentation 35 $ 238,877 $ 96,295 Arts Total 88 $ 2,770,542 $ 4,629,414 $ 2,770,542 $ - 0.00% Environment ENV-A Capacity Building - $ - $ - ENV-C Project and Programs 8 $ 180,364 $ 114,925 Environment Total 8 $ 146,390 $ 180,364 $ 114,925 $ 31,465 21.49% Page 1 of 20 Appendix A to Report GRA19002 No. of 2019 Budget 2019 Category Apps (Total) 2019 Requested Recommended Budget vs Recommended Communities, Culture & Heritage CCH - A CCH - Events 57 $ 782,985 $ 535,595 CCH - B CCH - New Projects 11 $ 165,092 $ 44,645 CCH - C CCH - Capacity Building 1 $ 6,900 $ - CCH Total 69 $ 564,972 $ 954,977 $ 580,240 -$ 15,268 -

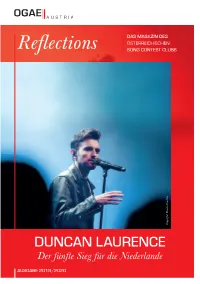

Reflections 3 Reflections

3 Refl ections DAS MAGAZIN DES ÖSTERREICHISCHEN Refl ections SONG CONTEST CLUBS AUSGABE 2019/2020 AUSGABE | TAUSEND FENSTER Der tschechische Sänger Karel Gott („Und samkeit in der großen Stadt beim Eurovision diese Biene, die ich meine, die heißt Maja …“) Song Contest 1968 in der Royal Albert Hall wurde vor allem durch seine vom böhmischen mit nur 2 Punkten den bescheidenen drei- SONG CONTEST CLUBS Timbre gekennzeichneten, deutschsprachigen zehnten Platz, fi ndet aber bis heute großen Schlager in den 1970er und 1980er Jahren zum Anklang innerhalb der ESC-Fangemeinde. Liebling der Freunde eingängiger U-Musik. Neben der deutschen Version, nahm Karel Copyright: Martin Krachler Ganz zu Beginn seiner Karriere wurde er Gott noch eine tschechische Version und zwei ÖSTERREICHISCHEN vom Österreichischen Rundfunk eingela- englische Versionen auf. den, die Alpenrepublik mit der Udo Jürgens- Hier seht ihr die spanische Ausgabe von „Tau- DUNCAN LAURENCE Komposition „Tausend Fenster“ zu vertreten. send Fenster“, das dort auf Deutsch veröff ent- Zwar erreichte der Schlager über die Ein- licht wurde. MAGAZINDAS DES Der fünfte Sieg für die Niederlande DIE LETZTE SEITE | ections Refl AUSGABE 2019/2020 2 Refl ections 4 Refl ections 99 Refl ections 6 Refl ections IMPRESSUM MARKUS TRITREMMEL MICHAEL STANGL Clubleitung, Generalversammlung, Organisation Clubtreff en, Newsletter, Vorstandssitzung, Newsletter, Tickets Eurovision Song Contest Inlandskorrespondenz, Audioarchiv [email protected] Fichtestraße 77/18 | 8020 Graz MARTIN HUBER [email protected] -

My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R. Fisher Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS By David R. Fisher A thesis submitted to the College of Music In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of David Fisher on March 29, 2006. ______________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee M ember The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables......................................................................................................................iv Abstract................................................................................................................................v 1. THE ORIGINS OF THE SHOEGAZER.........................................................................1 2. A BIOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE.………..………17 3. AN ANALYSIS OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS...............................28 4. LOVELESS AND ITS LEGACY...................................................................................50 BIBLIOGRAPHY..............................................................................................................63 -

UNDERSTANDING PORTRAYALS of LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS in HIP-HOP LYRICS SINCE 2009 By

ON THE BEAT: UNDERSTANDING PORTRAYALS OF LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS IN HIP-HOP LYRICS SINCE 2009 by Francesca A. Keesee A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degrees of Master of Science Conflict Analysis and Resolution Master of Arts Conflict Resolution and Mediterranean Security Committee: ___________________________________________ Chair of Committee ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Graduate Program Director ___________________________________________ Dean, School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Date: _____________________________________ Fall Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, VA University of Malta Valletta, Malta On the Beat: Understanding Portrayals of Law Enforcement Officers in Hip-hop Lyrics Since 2009 A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees of Master of Science at George Mason University and Master of Arts at the University of Malta by Francesca A. Keesee Bachelor of Arts University of Virginia, 2015 Director: Juliette Shedd, Professor School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Fall Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, Virginia University of Malta Valletta, Malta Copyright 2016 Francesca A. Keesee All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to all victims of police brutality. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am forever grateful to my best friend, partner in crime, and husband, Patrick. -

Fringe Season 1 Transcripts

PROLOGUE Flight 627 - A Contagious Event (Glatterflug Airlines Flight 627 is enroute from Hamburg, Germany to Boston, Massachusetts) ANNOUNCEMENT: ... ist eingeschaltet. Befestigen sie bitte ihre Sicherheitsgürtel. ANNOUNCEMENT: The Captain has turned on the fasten seat-belts sign. Please make sure your seatbelts are securely fastened. GERMAN WOMAN: Ich möchte sehen wie der Film weitergeht. (I would like to see the film continue) MAN FROM DENVER: I don't speak German. I'm from Denver. GERMAN WOMAN: Dies ist mein erster Flug. (this is my first flight) MAN FROM DENVER: I'm from Denver. ANNOUNCEMENT: Wir durchfliegen jetzt starke Turbulenzen. Nehmen sie bitte ihre Plätze ein. (we are flying through strong turbulence. please return to your seats) INDIAN MAN: Hey, friend. It's just an electrical storm. MORGAN STEIG: I understand. INDIAN MAN: Here. Gum? MORGAN STEIG: No, thank you. FLIGHT ATTENDANT: Mein Herr, sie müssen sich hinsetzen! (sir, you must sit down) Beruhigen sie sich! (calm down!) Beruhigen sie sich! (calm down!) Entschuldigen sie bitte! Gehen sie zu ihrem Sitz zurück! [please, go back to your seat!] FLIGHT ATTENDANT: (on phone) Kapitän! Wir haben eine Notsituation! (Captain, we have a difficult situation!) PILOT: ... gibt eine Not-... (... if necessary...) Sprechen sie mit mir! (talk to me) Was zum Teufel passiert! (what the hell is going on?) Beruhigen ... (...calm down...) Warum antworten sie mir nicht! (why don't you answer me?) Reden sie mit mir! (talk to me) ACT I Turnpike Motel - A Romantic Interlude OLIVIA: Oh my god! JOHN: What? OLIVIA: This bed is loud. JOHN: You think? OLIVIA: We can't keep doing this. -

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha E Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha_E_Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Runnin' (Trying To Live) 2Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3Oh!3 Feat. Katy Perry Starstrukk 3T Anything 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 5 Seconds of Summer She's Kinda Hot 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Seconds of Summer Hey Everybody 5 Seconds of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds of Summer Girls Talk Boys 5 Seconds of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds of Summer Amnesia 5 Seconds of Summer (Feat. Julia Michaels) Lie to Me 5ive When The Lights Go Out 5ive We Will Rock You 5ive Let's Dance 5ive Keep On Movin' 5ive If Ya Getting Down 5ive Got The Feelin' 5ive Everybody Get Up 6LACK Feat. J Cole Pretty Little Fears 7Б Молодые ветра 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc Donna 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 30 Seconds To Mars Rescue Me 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent Feat. Eminem & Adam Levine My Life 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg and Young Jeezy Major Distribution 101 Dalmatians (Disney) Cruella De Vil 883 Nord Sud Ovest Est 911 A Little Bit More 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 1927 If I Could "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Canadian Idiot A Bugs Life The Time Of Your Life A Chorus Line (Musical) What I Did For Love A Chorus Line (Musical) One A Chorus Line (Musical) Nothing A Goofy Movie After Today A Great Big World Feat. -

AUSTRALIAN SINGLES REPORT 19Th December, 2016 Compiled by the Music Network© FREE SIGN UP

AUSTRALIAN SINGLES REPORT 19th December, 2016 Compiled by The Music Network© FREE SIGN UP ARTIST TOP 50 Combines airplay, downloads & streams #1 SINGLE ACROSS AUSTRALIA Starboy 1 The Weeknd | UMA starboy Rockabye The Weeknd ft. Daft Punk | UMA 2 Clean Bandit | WMA Say You Won't Let Go 3 James Arthur | SME Riding the year out at #1 on the Artist Top 50 is The Weeknd’s undeniable hit Starboy ft. Daft Punk. Black Beatles Overtaking Clean Bandit’s Rockabye ft. Sean Paul & Anne-Marie which now sits at #2, Starboy has 4 Rae Sremmurd | UMA stuck it out and finally taken the crown. Vying for #1 since the very first issue of the Australian Singles Scars to your beautiful Report and published Artist Top 50, Starboy’s peak at #1 isn’t as clear cut as previous chart toppers. 5 Alessia Cara | UMA Capsize The biggest push for Starboy has always come from Spotify. Now on its eighth week topping the 6 Frenship | SME streaming service’s Australian chart, the rest of the music platforms have finally followed suit.Starboy Don't Wanna Know 7 Maroon 5 | UMA holds its peak at #2 on the iTunes chart as well as the Hot 100. With no shared #1 across either Starvi n g platforms, it’s been given a rare opportunity to rise. 8 Hailee Steinfeld | UMA Last week’s #1, Rockabye, is still #1 on the iTunes chart and #2 on Spotify, but has dropped to #5 on after the afterparty 9 Charli XCX | WMA the Hot 100. It’s still unclear whether there will be one definitive ‘summer anthem’ that makes itself Catch 22 known over the Christmas break. -

Perfect Setting, Distinctive Performances Portlands’ Pickathon MUSIC FESTIVAL

Music.Gear.Style. No.73 August 2015 Perfect Setting, Distinctive Performances Portlands’ Pickathon MUSIC FESTIVAL SPIN THE BLACK CIRCLE: New Albums from Low, Destroyer, The Arcs, Lianne La Havas, Dave Douglas, Robert Glasper, Stephen Micus, and More INTERVENTION RECORDS: A New Audiophile Reissue Label Strives to be Different THE AUDIOPHILE APARTMENT: Sound for Small Spaces l Analog Diversity from Monk Audio GamuT Combines Power and Finesse With Their M250i monoblocks l Digital Excellence From Gryphon, The Ultimate Silence from IsoTek, and more! WCT_TONE_Dec2014.indd 1 6/10/15 3:31 PM WE’VE DESIGNED THE PERFECT RECEIVER. MRX 710 / MRX 510 / MRX 310 NOW WE’LL PERFECT YOUR ROOM. AWARD-WINNING A/V RECEIVERS The most direct, economical route to outstanding music and home theater. Multiple channels of clean power, superb amplification with Advanced Load Monitoring for unrestrained dynamics. Even with the finest equipment and speakers perfectly positioned, the room can have a negative impact on sound quality. Dimensions, dead spots, archways, even furniture can turn it into an additional instrument adding unwanted coloration and resonances to sound. In minutes, ARC 1M adjusts for these effects so that the award-winning sound of the MRX isn’t lost in a less than perfect room. Now your Anthem gear can do what it does best: allow you to lose yourself in the music or movie. INCLUDES ANTHEM ROOM CORRECTION SYSTEM anthemAV.com 46 74 features tone style 11. PUBLISHER’S LETTER Old School: The Wino: 12. TONE TOON BeoCenter 9500 14 74 Cabernet 4 Ways