Biological Effects of Dispersants and Dispersed Oil on Surface and Deep Ocean Species

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acute Toxicity of Para-Nonylphenol to Saltwater Animals

Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, Vol. 19, No. 3, pp. 617±621, 2000 Printed in the USA 0730-7268/00 $9.00 1 .00 ACUTE TOXICITY OF PARA-NONYLPHENOL TO SALTWATER ANIMALS SUZANNE M. LUSSIER,*² DENISE CHAMPLIN,² JOSEPH LIVOLSI,² SHERRY POUCHER,³ and RICHARD J. PRUELL² ²U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Atlantic Ecology Division, 27 Tarzwell Drive, Narragansett, Rhode Island 02882 ³Science Applications International Corporation, 221 Third Street, Admiral's Gate, Newport, Rhode Island 02840, USA (Received 25 November 1998; Accepted 14 June 1999) AbstractÐpara-Nonylphenol (PNP), a mixture of alkylphenols used in producing nonionic surfactants, is distributed widely in surface waters and aquatic sediments, where it can affect saltwater species. This article describes a database for acute toxicity of PNP derived for calculating a national saltwater quality criterion. Using a ¯ow-through exposure system with measured concen- trations, we tested early life stages of four species of saltwater invertebrates and two species of ®sh. Static 96-h tests were also conducted on zoeal Homarus americanus, embryo-larval Mulinia lateralis, and larval Pleuronectes americanus. The number of organisms surviving the ¯ow-through test was measured at 2, 4, 8, and 12 h and daily through day 7. Mortality for most species plateaued by 96 h. The ranked sensitivities (96-h 50% lethal concentrations, measured in micrograms per liter) for the species tested were 17 for Pleuronectes americanus, 37.9 (48-h 50% effective concentration) for Mulinia lateralis, 59.4 for Paleomonetes vulgaris, 60.6 for Americamysis bahia (formerly Mysidopsis bahia), 61.6 for Leptocheirus plumulosos, 70 for Menidia beryllina, 71 for Homarus americanus, 142 for Cyprinodon variegatus, and .195 for Dyspanopius sayii. -

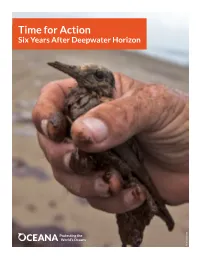

Time for Action

Time for Action Six Years After Deepwater Horizon Julie Dermansky “One of the lessons we’ve learned from this spill is that we need better regulations, better safety standards, and better enforcement when it comes to offshore drilling.” President Barack Obama June 15, 2010 Authors Acknowledgments Ingrid Biedron, Ph.D. The authors are grateful for the reviews, comments and and Suzannah Evans direction provided by Dustin Cranor, Claire Douglass, Michael April 2016 LeVine, Lara Levison, Kathryn Matthews, Ph.D., Jacqueline U.S. Coast Guard U.S. Savitz, Lora Snyder, Oona Watkins and Emory Wellman. 1 OCEANA | Time for Action: Six Years After Deepwater Horizon Executive Summary he Deepwater Horizon oil spill 2016, that show the damage the 2010 oil • Harmful oil and/or oil dispersant Tdevastated the Gulf of Mexico’s spill caused in the Gulf of Mexico. Scientists chemicals were found in about 80 marine life, communities and economy. are still working to understand the scale of percent of pelican eggs that were laid in Since the 2010 disaster, federal agencies devastation to wildlife, fisheries and human Minnesota, more than 1,000 miles from have done little to improve the safety of health. These catastrophic outcomes could the Gulf, where most of these birds offshore drilling using existing authorities happen in any region of the United States spend winters.3 and Congress has done virtually nothing where oil and gas activities are proceeding, • Oil exposure caused heart failure in to reduce the risk of another spill in our especially as those activities are moving juvenile bluefin and yellowfin tunas,4 waters or on our beaches. -

Oil + Dispersant

Effects of oil dispersants on the environmental fate, transport and distribution of spilled oil in marine ecosystems Don Zhao, Y. Gong, X. Zhao, J. Fu, Z. Cai, S.E. O’Reilly Environmental Engineering Program Department of Civil Engineering Auburn University, Auburn, AL 36849, USA Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Office of Environment, New Orleans, LA 70123, USA Outline • Roles of dispersants on sediment retention of oil compounds • Effects of dispersants on settling of suspended sediment particles and transport of oil compounds • Effects of dispersants and oil on formation of marine oil snow Part I. Effects of Oil Dispersants on Sediment Retention of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Gulf Coast Ecosystems Yanyan Gong1, Xiao Zhao1, S.E. O’Reilly2, Dongye Zhao1 1Environmental Engineering Program Department of Civil Engineering Auburn University, Auburn, AL 36849, USA 2Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Office of Environment, New Orleans, LA 70123, USA Gong et al. Environmental Pollution 185 (2014) 240-249 Application of Oil Dispersants • In the 2010 the DWH oil spill, BP applied ~2.1 MG of oil dispersants (Kujawinski et al., 2011) Corexit 9500A and Corexit 9527A • About 1.1 MG injected at the wellhead (pressure = 160 atm, temperature = 4 oC) (Thibodeaux et al., 2011) • Consequently, ~770,000 barrels (or ~16%) of the spilled oil were dispersed (Ramseur, 2010) Kujawinski, E.B. et al. (2011) Environ. Sci. Technol., 45, 1298-1306. Ramseur, J.L. (2010) www.crs.gov, R41531. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Spilled Oil • A class of principal persistent oil components The Macondo well oil contained ~3.9% PAHs by weight, and ~21,000 tons of PAHs were released during the 2010 spill (Reddy et al., 2011) PAHs are toxic, mutagenic, carcinogenic and persistent • Elevated concentrations of PAHs were reported during the DWH oil spill (EPA, 2010) Naphthalene Phenanthrene Pyrene Chrysene Benzo(a)pyrene Reddy, C.M. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Leel\Desktop\WA 2-15 DRP

DRAFT DETAILED REVIEW PAPER ON MYSID LIFE CYCLE TOXICITY TEST EPA CONTRACT NUMBER 68-W-01-023 WORK ASSIGNMENT 2-15 July 2, 2002 Prepared for L. Greg Schweer WORK ASSIGNMENT MANAGER U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY ENDOCRINE DISRUPTOR SCREENING PROGRAM WASHINGTON, D.C. BATTELLE 505 King Avenue Columbus, Ohio 43201 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................... 1 2.0 INTRODUCTION .............................................................. 2 2.1 DEVELOPING AND IMPLEMENTING THE ENDOCRINE DISRUPTOR SCREENING PROGRAM (EDSP).......................................... 2 2.2 THE VALIDATION PROCESS............................................. 2 2.3 PURPOSE OF THE REVIEW ............................................. 3 2.4 METHODS USED IN THIS ANALYSIS...................................... 4 2.5 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ....................................... 5 3.0 OVERVIEW AND SCIENTIFIC BASIS OF MYSID LIFE CYCLE TOXICITY TEST ........... 6 3.1 ECDYSTEROID SENSITIVITY TO MEASURED ENDPOINTS ................... 9 4.0 CANDIDATE MYSID TEST SPECIES ............................................ 11 4.1 AMERICAMYSIS BAHIA ................................................ 12 4.1.1 Natural History ................................................... 12 4.1.2 Availability, Culture, and Handling .................................. 12 4.1.3 Strengths and Weaknesses ....................................... 13 4.2 HOLMESIMYSIS COSTATA ............................................. 13 4.2.1 Natural History ................................................ -

Independent Human Health and Environmental Hazard

Independent Human Health and Environmental Hazard Assessments of Dispersant Chemicals in Australia, produced by NICNAS and CSIRO AMSA/National Plan preamble to the three independent reports by: NICNAS (April 2014) Chemicals used as oil dispersants in Australia: Stage 1. Identification of chemicals of low concern for human health NICNAS (October 2014) Chemicals used as oil dispersants in Australia: Stage 2. Summary report of the human health hazards of oil spill dispersant chemicals CSIRO (August 2015) A review of the ecotoxicological implications of oil dispersant use in Australian waters. The Australian National Plan Dispersant Strategy The Australian National Plan for Maritime Environmental Emergencies has had a longstanding dispersant response strategy that is transparent, fit for purpose and effective, and safe to use for people and the environment. At all stages of dispersant management: acceptance and purchase; storage and transport; and application in spill, the National Plan requires transparency. These requirements, results and processes are all published on the AMSA website. To ensure that Australia has suitable information to undertake all these steps, AMSA has always sought the best independent advice it could find. Most recently AMSA addressed questions of human health hazards and environmental hazards. Health hazard assessment by National Industrial Chemicals Notification and Assessment Scheme (NICNAS) NICNAS comprehensively addressed the question of dispersant health hazard in two stages. The first stage assessment identified 2 of 11 chemicals to be of low concern for human health. The second stage was a more full assessment that concluded that 7 of the 11 chemicals were of no concern. The remaining four were considered hazardous based on Safe Work Australia’s Approved Criteria for Classifying Hazardous Substances. -

Dispersants Edition

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS: DISPERSANTS EDITION Chemical dispersants break oil into smaller droplets, limiting the amount of oil that comes into contact with wildlife and shorelines. Many people question how they work and whether they are safe for people and animals. FIGURE 1. Dispersants, though rarely used, can be applied to oil spills. The surfactant molecules in dispersants help oil and water mix, creating small oil droplets that are more easily broken down by microbes than an oil slick. (Florida Sea Grant/Anna Hinkeldey) WHAT ARE DISPERSANTS AND burning, and dispersants — depending upon the WHAT DO THEY DO? incident.3,4 For example, booms can concentrate oil in Dispersants are a mixture of compounds whose an area for removal by skimmers, but they often fail in components work together to break oil slicks into rough sea conditions and are less effective in open small oil droplets (Figure 1). The small droplets are then water. Where dispersant use is permitted, and broken down by evaporation, sunlight, microbes, and environmental conditions (e.g., waves) indicate it could other natural processes.1 Dispersants work under a wide be effective, dispersants may better protect animals and range of temperature conditions. Their components and habitats. Dispersants are rarely used; but when they are, dispersed oil can be broken down by microbes as well.2 they are typically applied at the water’ surface. However, during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, responders WHEN AND WHERE ARE DISPERSANTS USED? also used dispersants directly at the source of the underwater blowout.5 There is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ technique for oil spill response.3 Decision-makers must weigh the WHAT IMPACTS DO DISPERSANTS environmental costs of each technique depending upon HAVE ON SEA LIFE? the scenario. -

Persistence, Fate, and Effectiveness of Dispersants Used During The

THE SEA GRANT and GOMRI PERSISTENCE, FATE, AND EFFECTIVENESS PARTNERSHIP OF DISPERSANTS USED DURING THE The mission of Sea Grant is to enhance the practical use and DEEPWATER HORIZON OIL SPILL conservation of coastal, marine Monica Wilson, Larissa Graham, Chris Hale, Emily Maung-Douglass, Stephen Sempier, and Great Lakes resources in and LaDon Swann order to create a sustainable economy and environment. There are 33 university–based The Deepwater Horizon (DWH) oil spill was the first spill that occurred Sea Grant programs throughout the coastal U.S. These programs in the deep ocean, nearly one mile below the ocean’s surface. The are primarily supported by large-scale applications of dispersants used at the surface and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration wellhead during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill raised many questions and the states in which the and highlighted the importance of understanding their effects on the programs are located. marine environment. In the immediate aftermath of the Deepwater Horizon spill, BP committed $500 million over a 10–year period to create the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative, or GoMRI. It is an independent research program that studies the effect of hydrocarbon releases on the environment and public health, as well as develops improved spill mitigation, oil detection, characterization and remediation technologies. GoMRI is led by an independent and academic 20–member research board. The Sea Grant oil spill science outreach team identifies the best available science from projects funded by GoMRI and others, and only shares peer- reviewed research results. Oiled waters in Orange Beach, Alabama. (NOAA photo) Emergency responders used a large (Figure 1).1,2 Before this event, scientists amount of dispersants during the 2010 did not know how effective dispersants DWH oil spill. -

The Role and Regulation of Dispersants in Oil Spill Response

Fighting Chemicals with Chemicals: The Role and Regulation of Dispersants in Oil Spill Response Charles L. Franklin and Lori J. Warner or most Americans, and many American environmen- dentnews.gov/ (last visited July 17, 2011) (searching reported tal lawyers, the tragic Deepwater Horizon oil spill of incidents in which dispersants were evaluated and used). Even 2010 provided the first close-up look at the role that so, their use has not been without controversy. One of the oil dispersants and surfactant chemicals (dispersants) first documented uses of dispersing agents occurred in 1967 Fplay in modern-day oil spill response efforts. While dispersants during the response to the Torrey Canyon tanker spill off the have been used for decades, dispersants played a particularly English Coast. DOT, EPA, The Exxon Valdez Oil Spill: A Report pivotal, if controversial role, in the Gulf spill response, osten- to the President, Doc. No. OSWER-89-VALDZ, (May 1989) sibly helping to reduce the onshore impact of the release. Dis- [herinafter Exxon Valdez Report], App. D-23. This early effort persants were a workhorse of the recovery effort, and in turn, proved catastrophic, however, as the chemicals used in the arguably might be credited with limiting the land impacts of effort—little more than industrial degreasing agents devel- the largest spill in history. For some, however, the central role oped for cleaning tanks—resulted in an “ecological disaster” that chemical dispersants played in the Gulf cleanup effort in which extensive mortalities of animals and algae occurred is more a cause for question than credit. This article reviews immediately, and the natural recovery was severely slowed and the historic use and regulation of oil dispersants in oil spill still incomplete in some areas ten years later. -

Acute Toxicity Responses of Two Crustaceans, Americamysis Bahia and Daphnia Magna, to Endocrine Disrupters

Journal of Health Science, 50(1) 97–100 (2004) 97 Acute Toxicity Responses of Two Crustaceans, Americamysis bahia and Daphnia magna, to Endocrine Disrupters Masashi Hirano,a Hiroshi Ishibashi,a Naomi Matsumura,a Yukiko Nagao,a Naoko Watanabe,a Akiko Watanabe,b Norio Onikura,b Katsuyuki Kishi,b and Koji Arizono*, a aFaculty of Environmental and Symbiotic Sciences, Prefectural University of Kumamoto, 3–1–100 Tsukide, Kumamoto 862–8502, Japan and bJapan Pulp and Paper Research Institute Inc., 5–13–11 Tokodai, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 300–26, Japan (Received September 12, 2003; Accepted September 17, 2003; Published online October 7, 2003) The acute toxicity of endocrine disrupters in two screening and testing systems for EDs have been crustaceans, Americamysis bahia (A. bahia) and Daph- established in the OECD (Organization for Eco- nia magna (D. magna), was investigated and the toxi- nomic Cooperation and Development) and U.S. EPA cological responses compared. Bisphenol A had the (Environmental Protection Agency).3,4) lowest toxicity to D. magna, the 48 hr median lethal Under laboratory culture, the mysid shrimp concentrations (LC50) values was 12.8 mg/l. However, Americamysis bahia (A. bahia), reaches sexual ma- the toxic sensitivity of A. bahia to bisphenol A was ap- turity in 12 to 20 days, depending on water tempera- proximately 10-fold higher than for D. magna (48 hr ture and diet.5) Normally, the female will have eggs LC ; 1.34 mg/l). The 48 hr LC of estradiol-17 was 50 50 in the ovary at approximately 12 days of age. The 2.97 and 1.69 mg/l in D. -

Bioaccumulation Potential of Surfactants: a Review © EOSCA

© EOSCA EOSCA European Oilfield Speciality Chemicals Association Bioaccumulation Potential of Surfactants: A Review © EOSCA This report was commissioned by the European Oilfield Specialty Chemical Association (EOSCA). EOSCA was founded in 1990 and has grown to an organisation comprising 40 full members and 7 associate members. As it stands today it represents almost all of the chemical manufacturers and chemical services companies involved in the supply and application of chemicals to Oil and Gas Operations in Europe. The primary function is to act as a focus of interest and concern on issues relating to Environmental and Safety Regulation. To this end it is recognised by government and operators as a first point of contact for chemical issues and is a fully recognised Non-Governmental Organisation within the OSPAR framework. It has the intention of acting as an advocacy group with regulatory and governmental bodies. EOSCA provides an opportunity for members to network with Health, Safety and Environmental Affairs professionals in the field of Oilfield Chemicals. Address for Correspondence: Graham Payne (Executive Secretary) Briar Technical Services Ltd 501 North Deeside Road Cults Aberdeen AB15 9ES Tel: +44 (0)1224 868827 Fax: +44 (0)1224 862503 [email protected] i © EOSCA EUROPEAN OILFIELD SPECIALITY CHEMICALS ASSOCIATION SUMMARY REPORT SURFACTANT BIOACCUMULATION REVIEW PROJECT Project funding: EOSCA Project Manager/Editor: Phil McWilliams ILAB Environmental Laboratory Contributors: Astrazeneca Limited, Brixham Environmental Laboratory Aquateam AS Chemex International Environmental and Resource Technology Limited Severn Trent Services The work performed in collating and evaluating the data on surfactant bioaccumulation reviewed in this report was funded entirely by EOSCA. The work was carried out over the period September 1999 to July 2000. -

Oil Spill Dispersants: Effi Cacy and Eff Ects

NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL REPORT KEY FINDINGS Oil Spill Dispersants: Effi cacy and Eff ects Oil dispersants are chemicals that change the chemical and physical properties of oil to enable it to mix with water more easily, in a similar manner to the way that dish detergents break up cooking oil on a skillet. By increasing the amount of oil that mixes into sea water, dispersants can reduce the potential contamination of shoreline habitats—but at the same time, a larger volume of water at varying depths becomes exposed to spilled oil. This report reviews ongoing research on the use of dispersants as an oil spill response technique and the impact of dispersed oil on marine and coastal ecosystems. The report concludes that more information on the potential benefi ts or adverse impacts of dispersant use is needed to make effective, timely decisions on using dispersants in response to an oil spill. 1. Decisions to use dispersants involve trade-offs. Oil dispersants break up slicks, enhancing the amount of oil that physically mixes into the water column and reducing the potential that oil will contaminate shoreline habitats or come into contact with birds, marine mammals, or other organisms in coastal ecosystems. At the same time, using dispersants increases the exposure of water column and sea fl oor life to spilled oil. 2. The window of opportunity for using dispersants is early, typically within hours to 1 or 2 days after an oil spill. After that, natural “weathering” of an oil slick on the surface of the sea, caused by impacts such as the heat from the sun or buffeting by waves, makes oil more diffi cult to disperse. -

Toxicity Testing Report Phillips 66 Ferndale Refinery Ferndale, Washington

TOXICITY TESTING REPORT PHILLIPS 66 FERNDALE REFINERY FERNDALE, WASHINGTON Prepared for Phillips 66 Ferndale Refinery 3901 Unick Road Ferndale, Washington 98248 Prepared by EcoAnalysts, Inc. 4770 NE View Drive PO Box 216 Port Gamble, WA 98364 Submittal Date: April 14, 2017 Client Contract Reference: Contract No. 4523507907 EcoAnalysts Report ID: 032117.01 Toxicity Testing Report Phillips 66 Ferndale Refinery All testing reported herein was performed consistent with our laboratory’s quality assurance program. All results are intended to be considered in their entirety, and EcoAnalysts is not responsible for use of less than the complete report. The test results summarized in this report apply only to the sample(s) evaluated. PREPARED BY ______________________________________ Meg Pinza Program Manager ______________________________________ Brian Hester Quality Assurance Officer Authors: Jay D. Word EcoAnalysts Report #032117.01 i EcoAnalysts, Inc. Toxicity Testing Report Phillips 66 Ferndale Refinery CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 2. METHODS 2 2.1 Sample Collection and Storage 2 2.2 Bioassay Testing 4 2.3 Organisms for Testing 4 2.4 Mysid, Inland Silverside, Topsmelt, and Herring Feeding 4 2.5 Water for Bioassay Testing 5 2.6 Sample Adjustment 5 2.7 Survival and Growth Tests 5 2.8 Data Management and Analysis 5 3. RESULTS 6 3.1 Pacific Herring (Clupea pallasii) Larval Chronic Test Results 6 3.2 Topsmelt (Atherinops affinis) Chronic Test Results 9 3.3 Mysid (Americamysis bahia) Chronic Test Results 12 3.4 Inland Silverside (Menidia beryllina) Chronic Test Results 15 4. QUALITY ASSURANCE/QUALITY CONTROL 18 4.1 Study Deviations 19 5. SUMMARY 20 6.