The Role and Regulation of Dispersants in Oil Spill Response

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

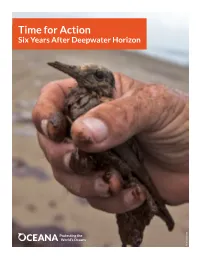

Time for Action

Time for Action Six Years After Deepwater Horizon Julie Dermansky “One of the lessons we’ve learned from this spill is that we need better regulations, better safety standards, and better enforcement when it comes to offshore drilling.” President Barack Obama June 15, 2010 Authors Acknowledgments Ingrid Biedron, Ph.D. The authors are grateful for the reviews, comments and and Suzannah Evans direction provided by Dustin Cranor, Claire Douglass, Michael April 2016 LeVine, Lara Levison, Kathryn Matthews, Ph.D., Jacqueline U.S. Coast Guard U.S. Savitz, Lora Snyder, Oona Watkins and Emory Wellman. 1 OCEANA | Time for Action: Six Years After Deepwater Horizon Executive Summary he Deepwater Horizon oil spill 2016, that show the damage the 2010 oil • Harmful oil and/or oil dispersant Tdevastated the Gulf of Mexico’s spill caused in the Gulf of Mexico. Scientists chemicals were found in about 80 marine life, communities and economy. are still working to understand the scale of percent of pelican eggs that were laid in Since the 2010 disaster, federal agencies devastation to wildlife, fisheries and human Minnesota, more than 1,000 miles from have done little to improve the safety of health. These catastrophic outcomes could the Gulf, where most of these birds offshore drilling using existing authorities happen in any region of the United States spend winters.3 and Congress has done virtually nothing where oil and gas activities are proceeding, • Oil exposure caused heart failure in to reduce the risk of another spill in our especially as those activities are moving juvenile bluefin and yellowfin tunas,4 waters or on our beaches. -

An Assessment of Marine Ecosystem Damage from the Penglai 19-3 Oil Spill Accident

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article An Assessment of Marine Ecosystem Damage from the Penglai 19-3 Oil Spill Accident Haiwen Han 1, Shengmao Huang 1, Shuang Liu 2,3,*, Jingjing Sha 2,3 and Xianqing Lv 1,* 1 Key Laboratory of Physical Oceanography, Ministry of Education, Ocean University of China, Qingdao 266100, China; [email protected] (H.H.); [email protected] (S.H.) 2 North China Sea Environment Monitoring Center, State Oceanic Administration (SOA), Qingdao 266033, China; [email protected] 3 Department of Environment and Ecology, Shandong Province Key Laboratory of Marine Ecology and Environment & Disaster Prevention and Mitigation, Qingdao 266100, China * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.L.); [email protected] (X.L.) Abstract: Oil spills have immediate adverse effects on marine ecological functions. Accurate as- sessment of the damage caused by the oil spill is of great significance for the protection of marine ecosystems. In this study the observation data of Chaetoceros and shellfish before and after the Penglai 19-3 oil spill in the Bohai Sea were analyzed by the least-squares fitting method and radial basis function (RBF) interpolation. Besides, an oil transport model is provided which considers both the hydrodynamic mechanism and monitoring data to accurately simulate the spatial and temporal distribution of total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH) in the Bohai Sea. It was found that the abundance of Chaetoceros and shellfish exposed to the oil spill decreased rapidly. The biomass loss of Chaetoceros and shellfish are 7.25 × 1014 ∼ 7.28 × 1014 ind and 2.30 × 1012 ∼ 2.51 × 1012 ind in the area with TPH over 50 mg/m3 during the observation period, respectively. -

Oil + Dispersant

Effects of oil dispersants on the environmental fate, transport and distribution of spilled oil in marine ecosystems Don Zhao, Y. Gong, X. Zhao, J. Fu, Z. Cai, S.E. O’Reilly Environmental Engineering Program Department of Civil Engineering Auburn University, Auburn, AL 36849, USA Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Office of Environment, New Orleans, LA 70123, USA Outline • Roles of dispersants on sediment retention of oil compounds • Effects of dispersants on settling of suspended sediment particles and transport of oil compounds • Effects of dispersants and oil on formation of marine oil snow Part I. Effects of Oil Dispersants on Sediment Retention of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Gulf Coast Ecosystems Yanyan Gong1, Xiao Zhao1, S.E. O’Reilly2, Dongye Zhao1 1Environmental Engineering Program Department of Civil Engineering Auburn University, Auburn, AL 36849, USA 2Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Office of Environment, New Orleans, LA 70123, USA Gong et al. Environmental Pollution 185 (2014) 240-249 Application of Oil Dispersants • In the 2010 the DWH oil spill, BP applied ~2.1 MG of oil dispersants (Kujawinski et al., 2011) Corexit 9500A and Corexit 9527A • About 1.1 MG injected at the wellhead (pressure = 160 atm, temperature = 4 oC) (Thibodeaux et al., 2011) • Consequently, ~770,000 barrels (or ~16%) of the spilled oil were dispersed (Ramseur, 2010) Kujawinski, E.B. et al. (2011) Environ. Sci. Technol., 45, 1298-1306. Ramseur, J.L. (2010) www.crs.gov, R41531. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Spilled Oil • A class of principal persistent oil components The Macondo well oil contained ~3.9% PAHs by weight, and ~21,000 tons of PAHs were released during the 2010 spill (Reddy et al., 2011) PAHs are toxic, mutagenic, carcinogenic and persistent • Elevated concentrations of PAHs were reported during the DWH oil spill (EPA, 2010) Naphthalene Phenanthrene Pyrene Chrysene Benzo(a)pyrene Reddy, C.M. -

Persistent Organic Pollutants in Marine Plankton from Puget Sound

Control of Toxic Chemicals in Puget Sound Phase 3: Persistent Organic Pollutants in Marine Plankton from Puget Sound 1 2 Persistent Organic Pollutants in Marine Plankton from Puget Sound By James E. West, Jennifer Lanksbury and Sandra M. O’Neill March, 2011 Washington Department of Ecology Publication number 11-10-002 3 Author and Contact Information James E. West Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife 1111 Washington St SE Olympia, WA 98501-1051 Jennifer Lanksbury Current address: Aquatic Resources Division Washington Department of Natural Resources (DNR) 950 Farman Avenue North MS: NE-92 Enumclaw, WA 98022-9282 Sandra M. O'Neill Northwest Fisheries Science Center Environmental Conservation Division 2725 Montlake Blvd. East Seattle, WA 98112 Funding for this study was provided by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, through a Puget Sound Estuary Program grant to the Washington Department of Ecology (EPA Grant CE- 96074401). Any use of product or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the authors or the Department of Fish and Wildlife. 4 Table of Contents Table of Contents................................................................................................................................................... 5 List of Figures ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 List of Tables ....................................................................................................................................................... -

Decontaminating Terrestrial Oil Spills: a Comparative Assessment of Dog Fur, Human Hair, Peat Moss and Polypropylene Sorbents

environments Article Decontaminating Terrestrial Oil Spills: A Comparative Assessment of Dog Fur, Human Hair, Peat Moss and Polypropylene Sorbents Megan L. Murray *, Soeren M. Poulsen and Brad R. Murray School of Life Sciences, University of Technology Sydney, PO Box 123, Sydney, NSW 2007, Australia; [email protected] (S.M.P.); [email protected] (B.R.M.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 4 June 2020; Accepted: 4 July 2020; Published: 8 July 2020 Abstract: Terrestrial oil spills have severe and continuing consequences for human communities and the natural environment. Sorbent materials are considered to be a first line of defense method for directly extracting oil from spills and preventing further contaminant spread, but little is known on the performance of sorbent products in terrestrial environments. Dog fur and human hair sorbent products were compared to peat moss and polypropylene sorbent to examine their relative effectiveness in adsorbing crude oil from different terrestrial surfaces. Crude oil spills were simulated using standardized microcosm experiments, and contaminant adsorbency was measured as percentage of crude oil removed from the original spilled quantity. Sustainable-origin absorbents made from dog fur and human hair were equally effective to polypropylene in extracting crude oil from non- and semi-porous land surfaces, with recycled dog fur products and loose-form hair showing a slight advantage over other sorbent types. In a sandy terrestrial environment, polypropylene sorbent was significantly better at adsorbing spilled crude oil than all other tested products. Keywords: crude oil; petroleum contamination; disaster management; land pollution 1. Introduction Crude oils are complex in composition and form the basis of many materials and fuels in high demand by global communities [1]. -

The Foundation for Global Action on Persistent Organic Pollutants: a United States Perspective

The Foundation for Global Action on Persistent Organic Pollutants: A United States Perspective Office of Research and Development Washington, DC 20460 EPA/600/P-01/003F NCEA-I-1200 March 2002 www.epa.gov Disclaimer Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. Cover page credits: Bald eagle, U.S. FWS; mink, Joe McDonald/Corbis.com; child, family photo, Jesse Paul Nagaruk; polar bear, U.S. FWS; killer whales, Craig Matkin. Contents Contributors ................................................................................................. vii Executive Summary ....................................................................................... ix Chapter 1. Genesis of the Global Persistent Organic Pollutant Treaty ............ 1-1 Why Focus on POPs? ................................................................................................. 1-2 The Four POPs Parameters: Persistence, Bioaccumulation, Toxicity, Long-Range Environmental Transport ......................................................... 1-5 Persistence ......................................................................................................... 1-5 Bioaccumulation ................................................................................................. 1-6 Toxicity .............................................................................................................. 1-7 Long-Range Environmental Transport .................................................................. 1-7 POPs -

Independent Human Health and Environmental Hazard

Independent Human Health and Environmental Hazard Assessments of Dispersant Chemicals in Australia, produced by NICNAS and CSIRO AMSA/National Plan preamble to the three independent reports by: NICNAS (April 2014) Chemicals used as oil dispersants in Australia: Stage 1. Identification of chemicals of low concern for human health NICNAS (October 2014) Chemicals used as oil dispersants in Australia: Stage 2. Summary report of the human health hazards of oil spill dispersant chemicals CSIRO (August 2015) A review of the ecotoxicological implications of oil dispersant use in Australian waters. The Australian National Plan Dispersant Strategy The Australian National Plan for Maritime Environmental Emergencies has had a longstanding dispersant response strategy that is transparent, fit for purpose and effective, and safe to use for people and the environment. At all stages of dispersant management: acceptance and purchase; storage and transport; and application in spill, the National Plan requires transparency. These requirements, results and processes are all published on the AMSA website. To ensure that Australia has suitable information to undertake all these steps, AMSA has always sought the best independent advice it could find. Most recently AMSA addressed questions of human health hazards and environmental hazards. Health hazard assessment by National Industrial Chemicals Notification and Assessment Scheme (NICNAS) NICNAS comprehensively addressed the question of dispersant health hazard in two stages. The first stage assessment identified 2 of 11 chemicals to be of low concern for human health. The second stage was a more full assessment that concluded that 7 of the 11 chemicals were of no concern. The remaining four were considered hazardous based on Safe Work Australia’s Approved Criteria for Classifying Hazardous Substances. -

Dispersants Edition

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS: DISPERSANTS EDITION Chemical dispersants break oil into smaller droplets, limiting the amount of oil that comes into contact with wildlife and shorelines. Many people question how they work and whether they are safe for people and animals. FIGURE 1. Dispersants, though rarely used, can be applied to oil spills. The surfactant molecules in dispersants help oil and water mix, creating small oil droplets that are more easily broken down by microbes than an oil slick. (Florida Sea Grant/Anna Hinkeldey) WHAT ARE DISPERSANTS AND burning, and dispersants — depending upon the WHAT DO THEY DO? incident.3,4 For example, booms can concentrate oil in Dispersants are a mixture of compounds whose an area for removal by skimmers, but they often fail in components work together to break oil slicks into rough sea conditions and are less effective in open small oil droplets (Figure 1). The small droplets are then water. Where dispersant use is permitted, and broken down by evaporation, sunlight, microbes, and environmental conditions (e.g., waves) indicate it could other natural processes.1 Dispersants work under a wide be effective, dispersants may better protect animals and range of temperature conditions. Their components and habitats. Dispersants are rarely used; but when they are, dispersed oil can be broken down by microbes as well.2 they are typically applied at the water’ surface. However, during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, responders WHEN AND WHERE ARE DISPERSANTS USED? also used dispersants directly at the source of the underwater blowout.5 There is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ technique for oil spill response.3 Decision-makers must weigh the WHAT IMPACTS DO DISPERSANTS environmental costs of each technique depending upon HAVE ON SEA LIFE? the scenario. -

Persistence, Fate, and Effectiveness of Dispersants Used During The

THE SEA GRANT and GOMRI PERSISTENCE, FATE, AND EFFECTIVENESS PARTNERSHIP OF DISPERSANTS USED DURING THE The mission of Sea Grant is to enhance the practical use and DEEPWATER HORIZON OIL SPILL conservation of coastal, marine Monica Wilson, Larissa Graham, Chris Hale, Emily Maung-Douglass, Stephen Sempier, and Great Lakes resources in and LaDon Swann order to create a sustainable economy and environment. There are 33 university–based The Deepwater Horizon (DWH) oil spill was the first spill that occurred Sea Grant programs throughout the coastal U.S. These programs in the deep ocean, nearly one mile below the ocean’s surface. The are primarily supported by large-scale applications of dispersants used at the surface and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration wellhead during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill raised many questions and the states in which the and highlighted the importance of understanding their effects on the programs are located. marine environment. In the immediate aftermath of the Deepwater Horizon spill, BP committed $500 million over a 10–year period to create the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative, or GoMRI. It is an independent research program that studies the effect of hydrocarbon releases on the environment and public health, as well as develops improved spill mitigation, oil detection, characterization and remediation technologies. GoMRI is led by an independent and academic 20–member research board. The Sea Grant oil spill science outreach team identifies the best available science from projects funded by GoMRI and others, and only shares peer- reviewed research results. Oiled waters in Orange Beach, Alabama. (NOAA photo) Emergency responders used a large (Figure 1).1,2 Before this event, scientists amount of dispersants during the 2010 did not know how effective dispersants DWH oil spill. -

Effects of Oil on Wildlife and Habitat the U.S

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Effects of Oil on Wildlife and Habitat The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Weathering reduces the more toxic elements in oil products over time as Service is the federal exposure to air, sunlight, wave and tidal action, and certain microscopic agency responsible for organisms degrade and disperse many of the nation’s fish oil. Weathering rates depend on factors such as type of oil, weather, and wildlife resources and temperature, and the type of shoreline one of the primary trustees and bottom that occur in the spill area. for fish, wildlife and habitat Types of Oil Although there are different types of at oil spills. oil, the oil involved in the Deepwater Horizon spill is classified as light crude. The Service is actively involved Light crude is moderately volatile and in response efforts related to the can leave a residue of up to one third of Deepwater Horizon oil spill that the amount spilled after several days. It occurred in the Gulf of Mexico on April leaves a film on intertidal resources and 20, 2010. Many species of wildlife, has the potential to cause long-term including some that are threatened or contamination. endangered, live along the Gulf Coast and could be impacted by the spill. Impacts to Wildlife and Habitat Oil causes harm to wildlife through Oil spills affect wildlife and their physical contact, ingestion, inhalation habitats in many ways. The severity and absorption. Floating oil can of the injury depends on the type and contaminate plankton, which includes quantity of oil spilled, the season and algae, fish eggs, and the larvae of MacKenzie FWS/Tom weather, the type of shoreline, and the various invertebrates. -

Marine Pollution in the Caribbean: Not a Minute to Waste

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Marine Public Disclosure Authorized Pollution in the Caribbean: Not a Minute to Waste Public Disclosure Authorized Standard Disclaimer: This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/the World Bank. The findings, interpreta- tions, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of the World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Copyright Statement: The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant per- mission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rose- wood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA, telephone 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470, http://www.copyright.com/. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA, fax 202-522-2422, e-mail [email protected]. -

Fate of Marine Oil Spills

FATE OF MARINE OIL SPILLS TECHNICAL INFORMATION PAPER 2 Introduction When oil is spilled into the sea it undergoes a number of physical and chemical changes, some of which lead to its removal from the sea surface, while others cause it to persist. The fate of spilled oil in the marine environment depends upon factors such as the quantity spilled, the oil’s initial physical and chemical characteristics, the prevailing climatic and sea conditions and whether the oil remains at sea or is washed ashore. An understanding of the processes involved and how they interact to alter the nature, composition and behaviour of oil with time is fundamental to all aspects of oil spill response. It may, for example, be possible to predict with confidence that oil will not reach vulnerable resources due to natural dissipation, so that clean-up operations will not be necessary. When an active response is required, the type of oil and its probable behaviour will determine which response options are likely to be most effective. This paper describes the combined effects of the various natural processes acting on spilled oil, collectively known as ‘weathering’. Factors which determine whether or not the oil is likely to persist in the marine environment are considered together with the implications for response operations. The fate of oil spilled in the marine environment has important implications for all aspects of a response and, consequently, this paper should be read in conjunction with others in this series of Technical Information Papers. Properties of oil Crude oils of different origin vary widely in their physical and chemical properties, whereas many refined products tend to have well-defined properties irrespective of the crude oil from which they are derived.