English Final-Open File-26December08

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12 Chapter 4.Pdf

CHAPTER-IV PROFILE OF THE STUDY AREA Present chapter deals with the profile of physical and socio-economic aspect of Daund Tahsil, namely physiography, drainage, climate, soils, vegetation, agriculture, irrigation, transportation.The study region is flat surface of 1289.86 Sq.Km.(128986 hector) aera covering 103 villages with one urban centre Daund. The river Bhima and its tributaries are major flow of Daund Tahsil. Along the south side of the river Bhima has fertile soils hence it is agriculturally well developed. Climatically this region belongs to semi -arid tract where months May and June have maximum temperature of 40 °C. Monsoon rainfall is prime source of this region, 600 mm rainfall during monsoon season.The rainfall amount declines sharply on westward and is responsible for evolution of landscape. Region has different soil types and holding varied moistures to produce agriculture goods. The region occupies less than 9.14 percent forest area of deciduous trees that found scattered grown in Daund tahsil. This region is predominance of agriculture in nature where Jawar, Bajra & Sugarcane are cultivated besides vegetables are produced in this region. Here is significant to note that study region accounting 35.5 % irrigated land which is mainly used for sugarcane. According to 2011 Census the region has 3,41,388 population consisting of 87.37 % rural and 12.63 % urban population. It is observed that 66.93 % population is engaged in agricultural activities.This region accrosses the national highway, state highway, major district roads, other district roads and village roads. Daund lies on railway junction and state highway. -

By Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Vidyavachaspati (Doctor of Philosophy) Faculty for Moral and Social Sciences Department Of

“A STUDY OF AN ECOLOGICAL PATHOLOGICAL AND BIO-CHEMICAL IMPACT OF URBANISATION AND INDUSTRIALISATION ON WATER POLLUTION OF BHIMA RIVER AND ITS TRIBUTARIES PUNE DISTRICTS, MAHARASHTRA, INDIA” BY Dr. PRATAPRAO RAMGHANDRA DIGHAVKAR, I. P. S. THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF VIDYAVACHASPATI (DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY) FACULTY FOR MORAL AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDHYAPEETH PUNE JUNE 2016 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the entire work embodied in this thesis entitled A STUDY OFECOLOGICAL PATHOLOGICAL AND BIOCHEMICAL IMPACT OF URBANISATION AND INDUSTRILISATION ON WATER POLLUTION OF BHIMA RIVER AND Its TRIBUTARIES .PUNE DISTRICT FOR A PERIOD 2013-2015 has been carried out by the candidate DR.PRATAPRAO RAMCHANDRA DIGHAVKAR. I. P. S. under my supervision/guidance in Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune. Such materials as has been obtained by other sources and has been duly acknowledged in the thesis have not been submitted to any degree or diploma of any University or Institution previously. Date: / / 2016 Place: Pune. Dr.Prataprao Ramchatra Dighavkar, I.P.S. DECLARATION I hereby declare that this dissertation entitled A STUDY OF AN ECOLOGICAL PATHOLOGICAL AND BIO-CHEMICAL IMPACT OF URBANISNTION AND INDUSTRIALISATION ON WATER POLLUTION OF BHIMA RIVER AND Its TRIBUTARIES ,PUNE DISTRICT FOR A PERIOD 2013—2015 is written and submitted by me at the Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The present research work is of original nature and the conclusions are base on the data collected by me. To the best of my knowledge this piece of work has not been submitted for the award of any degree or diploma in any University or Institution. -

INDEX Description Sub Title Page Nos. FOREWORD 7 SYSTEM MAP 8 ABBREVIATIONS USED 9 TERMS of REFERENCE 10 Chapter 1 DISASTERS –

INDEX Description Sub title Page Nos. FOREWORD 7 SYSTEM MAP 8 ABBREVIATIONS USED 9 TERMS OF REFERENCE 10 Chapter 1 DISASTERS – AN INTRODUCTION 11 to 12 1.0 Definition .. 1.1 Types of Disaster causing interruption to train s ervices .. 1.2 Lev els of Disaster causing interruption to train services .. 1.3 Declaration of a Railway a ccident/situation as a Disaster .. Chapter 2 DISASTER PREPAREDNESS - AVAILABILITY OF 13 to 15 RESOURCES 2.0 Introduction .. 2.1 Resource Unit - I .. 2.2 Resource Un it - II .. 2.3 Resource Unit - III .. 2.4 Resource Unit - IV .. Chapter 3 DISASTER PREPAREDNESS – ARMEs/ARTs 16 -17 3.0 Accident Relief Medical Equipment Van .. 3.1 Accident Relief Train .. 3.2 ART/ARME/MFD of adjacent zones .. 3.3 List of tunnels and l ocation of ART/ARME/MFD on either .. sides Chapter 4 SHARING OF RESOURCES WITH STATE 18 -19 GOVERNMENT AND OTHERS 4.0 Introduction .. 4.1 Relief Commissioners .. 4.2 Telephone Nos. of Senior Officers of Maharashtra Govt. .. 4.3 Air Force/Army/Navy As sistance .. Chapter 5 DISASTER RESPONSE –OVERVIEW 20 -21 5.0 Golden Hour .. 5.1 Disaster Syndrome .. 5.2 Three Different Phases of Disaster Response .. Chapter 6 DISASTER RESPONSE – INSTANT ACTION TEAM 22 -29 6.0 Instant Action Team (IAT) .. 6.1 Insta nt Action Team composition .. 6.2 Pre -accident checklist of preparation of Members of Instant .. ActionTeam 6.3 Duties of Guard, Driver, Train Superintendent/Travelling .. Ticket Examiner, AC Mechanic/Attendant and RPF/GRP Staff 6.4 Railway staff travel ling on the accident affected train . -

Savitribai Phule Pune University Pune, Maharashtra

SELF –STUDY REPORT For 2nd Cycle of Accreditation Submitted to NATIONAL ASSESSMENT AND ACCREDITATION COUNCIL P.O. Box No. 1075, Nagarbhave, Bangaluru – 560010 (India) Submitted by Varvand Gram Shikshan Sanstha‟s EKNATH SITARAM DIVEKAR ARTS, SCIENCE & COMMERCE COLLEGE Varvand, Tal – Daund, Dist. Pune Pin 412215 [Maharashtra] Affiliated to Savitribai Phule Pune University Pune, Maharashtra MAY 2017 1 CONTENTS Sr. No. Particulars Page Nos. 1 Contents 02 2 Annexture 03 3 NACC Steering Committee 04 4 Acknowledgement 05 5 Preface 06 6 Principal‘s Message 07 7 College Mission & Vision 09 8 Executive Summary and Criterion-wise 11 9 SWOC Analysis 18 10 College Profile 19 10 Criterion I Curricular Aspects 29 11 Criterion II: Teaching-Learning & Evaluation 47 12 Criterion III: Research, Consultancy and Extension 91 13 Criterion IV: Infrastructure and Learning Resources 138 14 Criterion V: Student Support and Progression 157 15 Criterion VI: Governance, Leadership & Management 187 16 Criterion VII: Innovation and Best Practices 205 17 C: Inputs from the Departments 215 1. Department of Marathi 215 2. Department of English 225 3. Department of Hindi 235 4. Department of History 243 5. Department of Psychology 251 6. Department of Economics 260 7. Department of Geography 267 8. Department of Chemistry 275 9. Department of Botany 288 10. Department of Mathematics 299 11. Department of Zoology 307 12. Department of Physics 317 13. Department of Commerce 325 14. Department of Computer Science 335 15. Department of Library Science 341 16. Department of Physical Education 347 Post Accreditation Initiatives Compliance for Peer Team Report 2 ANNEXURE Annexure I : Certificate of Compliance Annexure II : Approval of courses of Affiliating University Annexure III : UGC 2 (f) and 12 (B) Certificate Annexure IV : NAAC Accreditation Certificate Annexure V : Government Pemission Letter Annexure VI : List of teachers who have attended Refresher Course and Orientation Programme in the last five years. -

Executive Summary of EPL, Kurkumbh

Executive Summary of EPL, Kurkumbh Executive Summary 1 Executive Summary of EPL, Kurkumbh 1.0 INTRODUCTION Emcure Pharmaceuticals Ltd is situated at Kurkumbh, Pune. Company headquarter is situated in Pune, Kurkumbh is One of the unit of Emcure Pharmaceuticals Ltd. Emcure Pharmaceuticals Ltd., proposes to expansion of existing project at Plot No. D-24/24-1,MIDC Kurkumbh, Tal : Daund, Dist – Pune. MIDC has well developed infrastructure facilities like Road, Water & Drainage network. Daund Railway Station is 10 Km & Pune airport is about 75 Km away from the project site. Company falls under 5(f) & Category B of EIA Notification 2006. Emcure Pharmaceuticals headquartered at Pune in West India is a vertically integrated Indian pharmaceutical company. The company's products as API with tablets, capsules (both soft gel capsules and hard-gel capsules) and injectables. Established in 1983, Emcure was born out of the vision to create a healthcare company that would address the vast healthcare needs. Their commitment and drive have propelled there growth from a single manufacturing facility during the genesis, to a range of world class manufacturing facilities spread across API, formulations and biotechnology. 1.1 NEED OF THE PROJECT The Indian pharmaceutical sector has come a long way, being almost non-existent before 1970 to a prominent provider of healthcare products, meeting almost 95 per cent of the country's pharmaceuticals needs. The Industry today is in the front rank of India’s science-based industries with wide ranging capabilities in the complex field of drug manufacture and technology. It ranks very high in the third world, in terms of technology, quality and range of medicines manufactured. -

Copy of Freedom Fighters 18-19

LIST OF STATE GOVERNMENT FREEDOM FIGHTERS PENSIONERS PUNE DISTRICT 2018-19 S.NO FULL NAME OF PENSIONER RESIDENTIAL ADDRESS 1 2 4 B DHANLAXMI PARK FLAT NO 8 OPP P M T DEPO PAUD RD KOTHRUD 1 MAJIRE D B PUNE 411038 2 CHAUHAN M M 1206 B/9 APTE RD PUNE 411004 3 CHAUHAN MAYA 1206 B/9 APTE RD PUNE 411004 4 LIMAYE K N 102/103,ERANDWANE OPP.LAW COLLEGE PUNE 411004 875 YASHODHAM APTS BHANDARKAR ROAD LANE NO. 8 FLAT NO 7 5 JOSHI P A PUNE 411004 6 TENDULKAR M.M. C/O SURESH PRABHAKAR 503 EVORA FO KALYANINAGAR PUNE 411006 7 THORAT K J BHAVANI PETH PUNE 8 UDGIR SARUBAI DNYANESHWAR 1027 NANA PETH PUNE 411 002 9 KAMBLE MALLIBAI LAXMAN BHAWANI PRTH PUNE 10 TILEKAR AMBUBAI NARSIMHA 252 NANA PETH ^PUNE 411002 11 SAYYAD MADINA ANSAR HUSSAIN 266 NANA PETH PUNE 411002 12 DHUMAL CHANDRAKANT VITTHAL 313 NANA PETH ^PUNE 411002 13 PATNA KRISHNABAI BAJIRAO BHAVANI PETH PUNE 14 ZHENDE CHANDRABHGAGA DNYANDEO 282 NANAPETH BHAJI ALI PUNE 411002 15 SHAIKH HASHMATI IMAM 395 NANA PETH PUNE 411002 16 KHAIRE SHAKUNTALA PATIL 104 NANA PETH ASHOK CHOWK PUNE 411002 17 JORKAR VITTHAL MAHADEO 456 NANA PETH NEAR MODERN BEKARI PUNE 411002 18 SHIRKE DRUPADA S 195 NANA PETH MORE WADA OPP KIRAD HOSPITAL PUNE 411002 19 BORDE SHASHIKANT PETER 630 NANA PETH PUNE ^411002 20 JAKKA LAXMIBAI HANUMANT BHAVANI PETH PUNE 21 JOBANPUTRA KANCHAN SHANTILAL BHAVANI PETH PUNE 22 KADUSKAR PARVATI SHANKAR CO KUNDAN PUROHIT S NO.59,VADAR VASTI,KARVENAGAR 411052 23 KELKAR S C 149 RASTA PETH SHANTI SAGAR PUNE 411011 24 SHINDE PARVATI M 612,RASTA PETH.AZAD ALI MAJESTIC PLAZA BLDG. -

Faculty of Commerce - BUTR- 23.08.2014

List of Recognised P.G.Teacher & Research Ph.D.Guide Faculty Of Commerce - BUTR- 23.08.2014 Sr. BUTR Date College Name & Address Subject Recommended & Period No 1 BURT - Mr. Suhas Bhaskar Joshi Bussiness P.G. Teacher 23/08/2014 till 23.08.2014 Maharashtra Education Society, Garware Practice your age College of Commerce, Add. off Karve Road, Pune 2 BURT - Dr. Govind Mahadeo Dumbre Business Law P.G. Teacher 23/08/2014 till 23.08.2014 Pune Jilha Shikshan Mandal’s your age Annasaheb Waghire College, Add. Post- Otur, Tal. Junnar, Dist. Pune 3 BURT - Dr. Shivaji Dhondiba Takalkar Business Law P.G. Teacher 23/08/2014 till 23.08.2014 Gramonnati Mandal Arts, Commerce & your age Science College, Add. Tal. Junnar, Dist. Pune 4 BURT - Dr. Mukinda Baliram Khandare Business Law Ph.D Guide 23/08/2014 to 23.08.2014 Pune Jilha Shikshan Mandal 22/08/2022 Annasaheb Waghire College, Add. Post-Otur Tal. Junnar, Pune BURT - Dr. (Smt.) Shaila Deepak Desai Business Ph.D Guide 23/08/2014 to 23.08.2014 Brihan Maharashtra College of Economics 22/08/2022 Commerce, Pune – 411 004 5 Dr. Bejamee Gregory Lobo Business M.Phil 23/08/2014 to BURT - Pune Jilha Shikshan Mandal, Prof. Economics (By Papers & 22/08/2022 23.08.2014 Ramkrishna More Arts Commerce and Research) Science College, Add. Sec. No. 28, Ganganagar Akurdi Pradhikaran, Tal. Pimpari Chichwad, Dist. Pune 7 BURT - Dr. Devidas Gangadhar Ushir Maratha Business M.Phil 23/08/2014 to 23.08.2014 Vidya Prasarak Samaj KRT Arts BH Economics (By Papers & 22/08//2022 Commerce and AM Science College Research) (KTHM), Shivajinagar, Gangapur Road, Dist. -

State Home for Women Contact Details of Social Workers of Special Cell Pune District Protection Officers Under PWDV Act Pune Di

Contact details of Social Workers of Special Cell_Pune District Sr. NGO Name and address of Cell Name of Social workers Contact number 1 Superintendent of Police office, Rural Vaishali Ranade 9767502284 Sonali Salunkhe 8796515153 2 Baramati police station Sunita Shinde 7218099945 Rajendra Khartode 9096700515 3 Junnar police station Ganga Buke 9561961021 Kavita Kate 9970776299 4 Shirur police station Yogita Gund 77449680331 Gayatri Daundkar 9689904638 Protection Officers under PWDV Act_Pune District Sr no Office address Name of contact person Contact number 1 DWCDO Office Pune, District Pune Smt.Anjali Mojar 8689840222 2 ICDS Office,Maval,Taluka,Maval Smt.N.D.Devkar 9822959605 3 ICDS OfficeBaramati,Taluka,Baramati Smt.M.G. Jadhav 9404221070 4 ICDS Office,Bhor,Taluka Bhor Shr.M.H.Bhomkar 8796512326 5 ICDS Office Ambegaonl Taluka Shr.A.D.Shewale 9623693787 6 ICDS Office Haveli,Taluka Smt.B.L.Ghadge 9623215947 7 ICDS Office Shirur,Taluka,Shirur Shr.Y.R.Gadhave 9689799696 8 ICDS Office Junnar,Taluka Junnar Shr.A.K.Salukhe 9175988969 9 ICDS Office Indapur Taluka Indapur Shr.N.B.More 9762108429 10 ICDS Office Mulshi Taluka Mulshi Shr.P.N.Suruse 81499468579 11 ICDS Office Velhe Taluka Velhe Shr.S.B.Bandgar 9096210652 12 IcDs Office Daund Taluka Daund Smt.R.S.khandare 7774056692 13 ICDS Office Purandar Taluka Purandar Smt.K.Y.Chure 9503767478 14 ICDS office Khed Taluka Khed Shr.p.S.Nehrkar 70830156374 Family Counseling Centers (FCC)_ Pune District Sr. Name and address of FCC Name of contact person Contact number 1 Karve Institute of Social Services, Shri. Dipak Walodkar 020-60505006 18, Hill Side, Karve Nagar, Pune 2 Swadhar, An Institute For Dev. -

Village Map Sawale Taluka: Mawal Pimpari Malegaon Bk

Village Map Sawale Taluka: Mawal Pimpari Malegaon Bk. District: Pune Khand Karjat Inglun Kune Ansute !( Malegaon Kh. Andhra Sarovar Khed Kusur Dahuli Kambare Andar Mawal Wahangaon Borivali Kivale µ 3.5 1.75 0 3.5 7 10.5 Nagathali Kashal Kusavali km Thoran Jambhavali Kalhat Shirdhe Vadeshwar Rakaswadi Bhoyare Ukasan Pawalewadi Valavanti Mau Kondivade A.m. Somavadi Location Index Pale Nane Mawal Udhewadi Nigade Bhajgaon Vadivali Lake MoramarwadiKacharewadi Vaund Phalane District Index Vadavali Nandurbar Khandashi Brahmanwadi Ghonshet Bhandara Shiravata Sarovar Ambale Govitri Dhule Amravati Nagpur Gondiya Kondivade N.m Shire Badhalawadi Jalgaon Nesave Sai Velhavali Karanjgaon Takave Bk. Akola Wardha Nandgaon Umbare Navalakh Buldana Nashik Washim Chandrapur Jevare Mendhewadi Yavatmal Sangise Kambare N.m. Nanoli N.m. Aurangabad Pangaloli Belaj Palghar Mangarul Jalna Gadchiroli Budhavadi Nane Hingoli Khalapur Kune N.m. KarandoliVehergaon Shilatane Thane Paravadi Jadhavwadi Ahmednagar Parbhani Dahivali Mumbai Suburban Nanded Valvhan sarovar Valakh Rajpuri Mumbai Bid Takave Kh. Budhele Vadivale Pune Jambhul Raigarh Bidar Devghar Akurdi Latur Mundhavare Osmanabad Khadakale (CT) Kanhe Ambi Nanoli Tarf Chakan Varsoli Sangavi Jambavade Lonavala (M Cl) Waksai Karla Kamshet Nayagaon Sudumbare Satara Solapur Pathargaon Ratnagiri Boraj Brahman Wadi Varale Sangli Sadapur Sudhavadi Malawali N.m. Kusgaon Kh. Mohitewadi Dongargaon WADGAON (MAWAL) Maharashtra State Lonavale Lake Taje Pimpaloli !( Katavi Kolhapur Patan Chikhalse Ahirvade Sate Wadagaon (CT) Induri Devale Bhaje Sindhudurg Talegaon Dabhade (R) Kusgaon Bk. (Ct) Dharwad Aundholi Aundhe kh. Malewadi Kurvande Brahmanwadi Bedse Talegaon Dabhade (M Cl) Karunj Taluka Index Lohagad Sawantwadi Sadavali Ozarde Urse Adhe kh. DhalewadiMahagaon Baur Junnar Dudhivare Kadadhe Parandvadi Apati Somatane Gevhande Apati Prabhachiwadi Ambegaon Adavi Pale Pawan MawalShindgaon Thugaon Atvan Kale Ambegaon Yelase Malawali P.m. -

Dr. Thirumagal. J. Pillai Original Research Paper Management

Original Research Paper Volume-9 | Issue-9 | September - 2019 | PRINT ISSN No. 2249 - 555X | DOI : 10.36106/ijar Management SCHOOL DROPOUT TRENDS FOR ELEMENTARY AND SECONDARY EDUCATION IN PUNE DISTRICT (AN EXPLORATORY STUDY BASED ON U- DISE DATA) Dr. Thirumagal. J. Associate Professor, Indira Institute Of Management, Pune Pillai ABSTRACT Education is a basic human right for all and is important for everyone to make the most of their lives. The present situation of education in India is that, despite the fact that notable progress has been made in universalization of elementary education, as is clear from the improved access, near total enrollment and higher literacy levels, the situation is still characterized by irregular attendance and dropouts among children. It is specifically against this background that the present sponsored by ICSSR study is an attempt to explore the school dropout percentages among all educational levels in Pune district. This research work is descriptive in nature and the Secondary data has been collected of Pune districts especially of academic three years from 2013 to 2016 for all educational levels in talukas of Pune district. The observations and findings reveal maximum for all combined educational levels are a fluctuating increasing trend for Pune district, very few governmental actions could control the school dropouts. KEYWORDS : School Dropouts, UDISE, Secondary Data, Pune district, Elementary education, Secondary education. Pune Talukas. INTRODUCTION: The different Taluka (15 Talukas) figures are pooled together centered Student dropout from school is an important concern, which is visible on five administrative sub-divisions. These sub-divisions are defined through two indicators. -

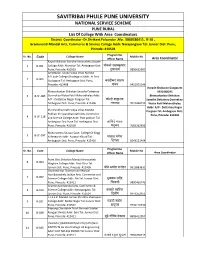

PUNE RURAL List of College with Area Coordinators District Coordinator -Dr.Shrikant Fulsundar ,Mo

SAVITRIBAI PHULE PUNE UNIVERSITY NATIONAL SERVICE SCHEME PUNE RURAL List Of College With Area Coordinators District Coordinator -Dr.Shrikant Fulsundar ,Mo. 9860286411, B-10 , Gramonnati Mandal Arts, Commerce & Science College Addr: Narayangaon Tal: Junnar Dist: Pune, Pincode: 410504 Programme Sr. No. Code College Name Mobile No Officer Name Area Coordinator Rayat Shikshan Sanstha Annasaheb Aawate 1 B-001 College Addr: Manchar Tal: Ambegaon Dist: पोकळे संजयकुमार Pune, Pincode: 410503 तुकाराम 9850652907 Ambegaon Taluka Vidya Vikas Mandal B.D.Kale College Ghodegaon Addr: At Post 2 B-005 Godegaon Tal: Ambegaon Dist: Pune, करंदीकर वभ Pincode: 412408 शंकर 9421001146 Korade Shakurao Gangaram Bhimashankar Shikshan Sanstha Dattatray 9922468295 3 B-SF-085 Govindrao Walse Patil Mahavidhylay Addr: Bhimashankar Shikshan A/P - Dattatray Nagar Pargaon Tal: कोरडे शाकुराव Sanstha Dattatray Govindrao Ambegaon Dist: Pune, Pincode: 412406 गंगाराम 9922468295 Walse Patil Mahavidhylay Addr: A/P - Dattatray Nagar Shri Pandharinath Vidya Vikas Mandal Pargaon Tal: Ambegaon Dist: Pokhari Shri pandharinath Arts Commerce Pune, Pincode: 412406 4 B-SF-118 and Science College Addr: Post pokhari Tal Ambegaon Dist Pune Tal: Ambegaon Dist: कािशदे यादव Pune, Pincode: 410509 मधुकर 7083262996 Maharashtra Shasan Govt. College Of Engg. 5 B-SF-097 & Research Addr: Awasari Khurd Tal: पांचाळ मंगेश Ambegaon Dist: Pune, Pincode: 412405 िदगंबर 8149121404 Programme Sr. No. Code College Name Mobile No Officer Name Area Coordinator Pune Jilha Shikshan Mandal Annasaheb 6 B-004 Waghire College Addr: Post-Otur Tal: Junnar Dist: Pune, Pincode: 412409 बीबे अमोल मनोहर 9623883631 Dnyaneshwar Gramonnati Mandal Hon.Balasaheb Jadhav Arts, Commerce and 7 B-007 Science College Addr: Ale Tal: Junnar Dist: भुजबळ रवीं Pune, Pincode: 412411 िचमाजी 9890460746 Gramonnati Mandal Arts, Commerce & 8 B-010 Science College Addr: Narayangaon Tal: कांबळे िल Junnar Dist: Pune, Pincode: 410504 िदलीप 8446252951 J.T.S.S.P. -

Center Code Center Name Center Address Center Incharge 1 Tilak

CenterList Center Code Center Name Center Address Center Incharge 1 Tilak Maharashtra Gultekadi,Pune Mr. Yogesh Landge Vidyapeeth, Pune 2 TMV Mumbai Office Mukhyadhyapak bhavan, 4 Mr. Belvalkar th floor, Nityananda swami hall, Sion,(W) Mumbai 3 TMV Belapur Office Great eastern chambers, Plot Mr. Vipul Dudhaskar no. 28, Sect. No. 11, CBD Belapur, Navi Mumbai 4 TMV Sadashiv Peth 1242, Sadashiv Peth Ms. Prdnya Peshwe 5 TMV Narayan Peth 568, Narayan Peth Mr. Mangesh Pharande 6 TMV Model Colony Deep Bungalow Chowk, Prof. Sarjerao Model Colony, Shivajinagar Pingale/ Prof. Nilesh Bhoite 7 TMV Baner Shivranjan Complex, S. No. Shri Sudhir Soman 12, Someshwarwadi, Baner, Pashan 8 TMV Delhi Kesari-Maratha Trust, 109, Mr. Bhatia PTI Building, New Delhi. 9 TMV Nigdi Sector no. 25, Sindhunagar, mr Pradhikaran, Nigdi 14 TMV Sangli Campus Lokmanya Trust Sadan, Plot Mr.Manohar Peshve No.67-70, Industrial Estate, Madhavnagar Road, Sangli. 25 A. R. Burla Mahila Varishta 213, Sakhar Peth, (Ashikal Mr. Rajendra Shendge Mahavidyalaya, Solapur Maidan) P.B.No.510, Solapur. 26 Abhinav College of Eng & First Floor, Chitco Center, Mr Sudhir Dixit Polytechnic (Nashik) Vakilwadi, Near Panchavati Hotel, Nashik 27 Abhinav College of Eng & 727, Budhwar Peth, Mr. Sudhir Dixit Polytechnic (Kasba Peth) Sawatamali Bhavan, 2nd Floor, Above Cosmos Bank, On Lalmahal - Phadke Haud Road, Pune - 411 002 28 Abhinav College of Eng and 601, Paradise Tower, Mr. Sudhir Dixit Polytechnic (Naupada) Gokhale Road, Naupada, Thane (W), 29 Abhinav College of DNC College Campus, DNC Mr. Sudhir I Dixit Engineering and Polytech Road, Dombivali (E) (Dombivali) 30 Abhinav Institute of Kolgiri Nagar, Hotgi Road, Shri, Shrishail Technology, (Navodya Near Majarewadi, Solapur.