1 Getting a Knighthood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prvních Deset Abelových Cen Za Matematiku

Prvních deset Abelových cen za matematiku The first ten Abel Prizes for mathematics [English summary] In: Michal Křížek (author); Lawrence Somer (author); Martin Markl (author); Oldřich Kowalski (author); Pavel Pudlák (author); Ivo Vrkoč (author); Hana Bílková (other): Prvních deset Abelových cen za matematiku. (English). Praha: Jednota českých matematiků a fyziků, 2013. pp. 87–88. Persistent URL: http://dml.cz/dmlcz/402234 Terms of use: © M. Křížek © L. Somer © M. Markl © O. Kowalski © P. Pudlák © I. Vrkoč Institute of Mathematics of the Czech Academy of Sciences provides access to digitized documents strictly for personal use. Each copy of any part of this document must contain these Terms of use. This document has been digitized, optimized for electronic delivery and stamped with digital signature within the project DML-CZ: The Czech Digital Mathematics Library http://dml.cz Summary The First Ten Abel Prizes for Mathematics Michal Křížek, Lawrence Somer, Martin Markl, Oldřich Kowalski, Pavel Pudlák, Ivo Vrkoč The Abel Prize for mathematics is an international prize presented by the King of Norway for outstanding results in mathematics. It is named after the Norwegian mathematician Niels Henrik Abel (1802–1829) who found that there is no explicit formula for the roots of a general polynomial of degree five. The financial support of the Abel Prize is comparable with the Nobel Prize, i.e., about one million American dollars. Niels Henrik Abel (1802–1829) M. Křížek a kol.: Prvních deset Abelových cen za matematiku, JČMF, Praha, 2013 87 Already in 1899, another famous Norwegian mathematician Sophus Lie proposed to establish an Abel Prize, when he learned that Alfred Nobel would not include a prize in mathematics among his five proposed Nobel Prizes. -

Cadenza Document

2017/18 Whole Group Timetable Semester 1 Mathematics Module CMIS Room Class Event ID Code Module Title Event Type Day Start Finish Weeks Lecturer Room Name Code Capacity Size 3184417 ADM003 Yr 1 Basic Skills Test Test Thu 09:00 10:00 18-20 Tonks, A Dr Fielding Johnson South Wing FJ SW 485 185 Basement Peter Williams PW Lecture Theatre 3198490 ADM003 Yr 1 Basic Skills Test Test Thu 09:00 10:00 18-20 Leschke K Dr KE 323, 185 KE 101, ADR 227, MSB G62, KE 103 3203305 ADM003 Yr 1 Basic Skills Test Test Thu 09:00 10:00 18-20 Hall E J C Dr Attenborough Basement ATT LT1 204 185 Lecture Theatre 1 3216616 ADM005 Yr 2 Basic Skills Test Test Fri 10:00 11:00 18 Brilliantov N BEN 149 Professor F75b, MSB G62, KE 103, KE 323 2893091 MA1012 Calculus & Analysis 1 Lecture Mon 11:00 12:00 11-16, Tonks, A Dr Ken Edwards First Floor KE LT1 249 185 18-21 Lecture Theatre 1 2893092 MA1012 Calculus & Analysis 1 Lecture Tue 11:00 12:00 11-16, Tonks, A Dr Attenborough Basement ATT LT1 204 185 18-21 Lecture Theatre 1 2893129 MA1061 Probability Lecture Thu 10:00 11:00 11-16, Hall E J C Dr Ken Edwards First Floor KE LT1 249 185 18-21 Lecture Theatre 1 2893133 MA1061 Probability Lecture Fri 11:00 12:00 11-16, Hall E J C Dr Bennett Upper Ground Floor BEN LT1 244 185 18-21 Lecture Theatre 1 2902659 MA1104 ELEMENTS OF NUMBER Lecture Tue 13:00 14:00 11-16, Goedecke J Ken Edwards Ground Floor KE LT3 150 100 THEORY 18-21 Lecture Theatre 3 2902658 MA1104 ELEMENTS OF NUMBER Lecture Wed 10:00 11:00 11-16, Goedecke J Astley Clarke Ground Floor AC LT 110 100 THEORY 18-21 Lecture -

Banknote Character Advisory Committee Minutes

BANKNOTE CHARACTER ADVISORY COMMITTEE (1) MINUTES Bank of England, Threadneedle Street 13.45 ‐ 15.00: 14 March 2018 Advisory Committee Members: Ben Broadbent (Chair), Sir David Cannadine, Victoria Cleland, Sandy Nairne, Baroness Lola Young Also present: Head of Banknote Resilience Programme Manager, Banknote Transformation Programme Senior Manager, Banknote Development Secretary to the Committee Minutes 1 Introduction and background 1.1 The Chair welcomed the Committee. He reminded members that their discussions should remain confidential. 1.2 Following the successful launch of the £5 and £10, the Bank was considering plans to launch a polymer £50. Governors and Court had approved a polymer £50 and the Banknote Character Advisory Committee had been re‐convened. 1.3 The Chair advised that the Chancellor’s Spring Statement the previous day had announced a call for evidence relating to the future of cash. The results of this exercise could impact the future of the £50 and it would be inappropriate for the Bank to press forward with a polymer £50 while the Government was considering the future denominational mix. 1.4 The closing date for receipt of evidence is 5 June and a decision might be expected around the Autumn budget. If HM Treasury decided to continue with the denomination and the Bank chose to develop a polymer £50, the Bank could presumptively make an announcement in early 2019 to avoid the public nomination process spanning Christmas 2018. 1 2 Equality considerations for selecting the field 2.1 The Bank reminded the Committee that equality considerations need to be consciously considered during the character selection process. -

The Atiyah-Singer Index Theorem, Formulated and Proved in 1962–3, Is a Vast Generalization to Arbitrary Elliptic Operators on Compact Manifolds of Arbitrary Dimension

THE ATIYAH-SINGER INDEX THEOREM DANIEL S. FREED In memory of Michael Atiyah Abstract. The Atiyah-Singer index theorem, a landmark achievement of the early 1960s, brings together ideas in analysis, geometry, and topology. We recount some antecedents and motivations; various forms of the theorem; and some of its implications, which extend to the present. Contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Antecedents and motivations from algebraic geometry and topology 3 2.1. The Riemann-Roch theorem 3 2.2. Hirzebruch’s Riemann-Roch and Signature Theorems 4 2.3. Grothendieck’s Riemann-Roch theorem 6 2.4. Integrality theorems in topology 8 3. Antecedents in analysis 10 3.1. de Rham, Hodge, and Dolbeault 10 3.2. Elliptic differential operators and the Fredholm index 12 3.3. Index problems for elliptic operators 13 4. The index theorem and proofs 14 4.1. The Dirac operator 14 4.2. First proof: cobordism 16 4.3. Pseudodifferential operators 17 4.4. A few applications 18 4.5. Second proof: K-theory 18 5. Variations on the theme 19 5.1. Equivariant index theorems 19 5.2. Index theorem on manifolds with boundary 21 5.3. Real elliptic operators 22 5.4. Index theorems for Clifford linear operators 22 arXiv:2107.03557v1 [math.HO] 8 Jul 2021 5.5. Families index theorem 24 5.6. Coverings and von Neumann algebras 25 6. Heat equation proof 26 6.1. Heat operators, zeta functions, and the index 27 6.2. The local index theorem 29 6.3. Postscript: Whence the Aˆ-genus? 31 7. Geometric invariants of Dirac operators 32 7.1. -

The Royal Society of Edinburgh Issue 15 • Winter 2006

news THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH ISSUE 15 • WINTER 2006 RESOURCE THE NEWSLETTER OF SCOTLAND’S NATIONAL ACADEMY Microcrystals promise major medical benefits A new technology being developed in Scotland could transform the treatment of many diseases by enabling protein medicines that currently need to be injected, to be taken with an inhaler. Recognising the importance of this breakthrough, Dr Marie Claire Parker was presented with the nation’s top award for innovation at a Ceremony held in the Royal Museum of Scotland on 27 October 2006. Dr Parker is CEO of XstalBio Ltd, a University of Glasgow and University of Strathclyde spin-out company, which developed as a result of an RSE/Scottish Enterprise Enterprise Fellowship held by Dr Parker in 2001. The Gannochy Trust Innovation Award of the Royal Society of Edinburgh has been created to encourage and reward Scotland’s young innovators for work which benefits Scotland’s wellbeing. This coveted award also carries a cheque for £50,000 and a specially commissioned gold medal, which was presented to Dr Parker by the President of the RSE, Sir Michael Atiyah. Dr Parker plans to use the £50,000 award to help develop the manufacturing process of stable, cost-effective vaccines and the advancement of a high quality biotechnology manufacturing company in Scotland, boosting our economy. Events around Scotland Christmas Lecture 2006 International Exchanges Recognising Excellence GANNOCHY TRUST INNOVATION AWARD OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH Entitled “Protein-coated Microcrystal (PCMC) Technology”, Dr Parker’s new process can attach proteins such as insulin to crystals that are so tiny (between one and five thousandths of a millimetre) that they can be inhaled, allowing the drug to enter the body via the lung. -

17 Oct 2019 Sir Michael Atiyah, a Knight Mathematician

Sir Michael Atiyah, a Knight Mathematician A tribute to Michael Atiyah, an inspiration and a friend∗ Alain Connes and Joseph Kouneiher Sir Michael Atiyah was considered one of the world’s foremost mathematicians. He is best known for his work in algebraic topology and the codevelopment of a branch of mathematics called topological K-theory together with the Atiyah-Singer index theorem for which he received Fields Medal (1966). He also received the Abel Prize (2004) along with Isadore M. Singer for their discovery and proof of the index the- orem, bringing together topology, geometry and analysis, and for their outstanding role in building new bridges between mathematics and theoretical physics. Indeed, his work has helped theoretical physicists to advance their understanding of quantum field theory and general relativity. Michael’s approach to mathematics was based primarily on the idea of finding new horizons and opening up new perspectives. Even if the idea was not validated by the mathematical criterion of proof at the beginning, “the idea would become rigorous in due course, as happened in the past when Riemann used analytic continuation to justify Euler’s brilliant theorems.” For him an idea was justified by the new links between different problems which it illuminated. Our experience with him is that, in the manner of an explorer, he adapted to the landscape he encountered on the way until he conceived a global vision of the setting of the problem. Atiyah describes here 1 his way of doing mathematics2 : arXiv:1910.07851v1 [math.HO] 17 Oct 2019 Some people may sit back and say, I want to solve this problem and they sit down and say, “How do I solve this problem?” I don’t. -

Sir Michael Atiyah the ASIAN JOURNAL of MATHEMATICS

.'•V'pXi'iMfA Sir Michael Atiyah THE ASIAN JOURNAL OF MATHEMATICS Editors-in-Chief Shing-Tung Yau, Harvard University Raymond H. Chan, Chinese University of Hong Kong Editorial Board Richard Brent, Oxford University Ching-Li Chai, University of Pennsylvania Tony F. Chan, University of California, Los Angeles Shiu-Yuen Cheng, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology John Coates, Cambridge University Ding-Zhu Du, University of Minnesota Kenji Fulcaya, Kyoto University Hillel Furstenberg, Hebrew University of Jerusalem Jia-Xing Hong, Fudan University Thomas Kailath, Stanford University Masaki Kashiwara, Kyoto University Ka-Sing Lau, Chinese University of Hong Kong Jun Li, Stanford University Chang-Shou Lin, National Chung Cheng University Xiao-Song Lin, University of California, Riverside Raman Parimala, Tata Institute of Fundamental Research Duong H. Phong, Columbia University Gopal Prasad, Michigan University Hyam Rubinstein, University of Melbourne Kyoji Saito, Kyoto University Jalal Shatah, Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences Saharon Shelah, Hebrew University of Jerusalem Leon Simon, Stanford University Vasudevan Srinivas, Tata Institue of Fundamental Research Srinivasa Varadhan, Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences Vladimir Voevodsky, Northwestern University Jeff Xia, Northwestern University Zhou-Ping Xin, Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences Horng-Tzer Yau, Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences Mathematics in the Asian region has grown tremendously in recent years. The Asian Journal of Mathematics (ISSN 1093-6106), from International Press, provides a forum for these developments, and aims to stimulate mathematical research in the Asian region. It publishes original research papers and survey articles in all areas of pure mathematics, and theoretical applied mathematics. High standards will be applied in evaluating submitted manuscripts, and the entire editorial board must approve the acceptance of any paper. -

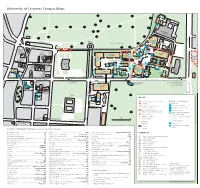

University of Leicester Campus Maps

University of Leicester Campus Maps 9 9 1 Vi 5 ctoria Par Pay a k A nd Displa y parking P Coach Drive Car Park n o DAVID WILSON s g n n h i LIBRARY o J W g h t n i u Freemen’s d l o e S i Common F Car Park £ NUFFIELD FITNESS CENTRE 3 2 1 To A6 Exit only To Train Station To Salisbury Road; To Counselling Service: London Road Freemen’s Common Health Centre; Freemen’s Common and Nixon Court Houses (500m) 1199 4 MAP KEY Campus entrance gate with barrier Wheelchair access information Exit only Building access: (Embrace Arts) Pre-booked parking for visitors – Full access to all floors please use entrance 1 Mostly accessible (see text) Occasional visitor parking – Ground floor only please check availability in advance Toilets accessible to wheelchair CRF One-way system users within building Entrance to building Entrance suitable for wheelchair To Prospect House Santander Bank access and Readson House To Opal Court £ Bookshop Entrance with ramp Bus Stop Slope over 10% Crossing Car parking space for disabled drivers Parking Location of Departments (Please see map key for building references) P AccessAbility Centre ....................................................................LIB English ......................................................................................ATT Physics and Astronomy ..............................Physics and Astronomy BUILDING KEY Accommodation Office ...............................................................CW English Language Teaching Unit ..............................Readson House Politics and International -

Notices of the American Mathematical

ISSN 0002-9920 Notices of the American Mathematical Society AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Graduate Studies in Mathematics Series The volumes in the GSM series are specifically designed as graduate studies texts, but are also suitable for recommended and/or supplemental course reading. With appeal to both students and professors, these texts make ideal independent study resources. The breadth and depth of the series’ coverage make it an ideal acquisition for all academic libraries that of the American Mathematical Society support mathematics programs. al January 2010 Volume 57, Number 1 Training Manual Optimal Control of Partial on Transport Differential Equations and Fluids Theory, Methods and Applications John C. Neu FROM THE GSM SERIES... Fredi Tro˝ltzsch NEW Graduate Studies Graduate Studies in Mathematics in Mathematics Volume 109 Manifolds and Differential Geometry Volume 112 ocietty American Mathematical Society Jeffrey M. Lee, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, American Mathematical Society TX Volume 107; 2009; 671 pages; Hardcover; ISBN: 978-0-8218- 4815-9; List US$89; AMS members US$71; Order code GSM/107 Differential Algebraic Topology From Stratifolds to Exotic Spheres Mapping Degree Theory Matthias Kreck, Hausdorff Research Institute for Enrique Outerelo and Jesús M. Ruiz, Mathematics, Bonn, Germany Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Spain Volume 110; 2010; approximately 215 pages; Hardcover; A co-publication of the AMS and Real Sociedad Matemática ISBN: 978-0-8218-4898-2; List US$55; AMS members US$44; Española (RSME). Order code GSM/110 Volume 108; 2009; 244 pages; Hardcover; ISBN: 978-0-8218- 4915-6; List US$62; AMS members US$50; Ricci Flow and the Sphere Theorem The Art of Order code GSM/108 Simon Brendle, Stanford University, CA Mathematics Volume 111; 2010; 176 pages; Hardcover; ISBN: 978-0-8218- page 8 Training Manual on Transport 4938-5; List US$47; AMS members US$38; and Fluids Order code GSM/111 John C. -

NEWSLETTER Issue: 481 - March 2019

i “NLMS_481” — 2019/2/13 — 11:04 — page 1 — #1 i i i NEWSLETTER Issue: 481 - March 2019 HILBERT’S FRACTALS CHANGING SIXTH AND A-LEVEL PROBLEM GEOMETRY STANDARDS i i i i i “NLMS_481” — 2019/2/13 — 11:04 — page 2 — #2 i i i EDITOR-IN-CHIEF COPYRIGHT NOTICE Iain Moatt (Royal Holloway, University of London) News items and notices in the Newsletter may [email protected] be freely used elsewhere unless otherwise stated, although attribution is requested when reproducing whole articles. Contributions to EDITORIAL BOARD the Newsletter are made under a non-exclusive June Barrow-Green (Open University) licence; please contact the author or photog- Tomasz Brzezinski (Swansea University) rapher for the rights to reproduce. The LMS Lucia Di Vizio (CNRS) cannot accept responsibility for the accuracy of Jonathan Fraser (University of St Andrews) information in the Newsletter. Views expressed Jelena Grbic´ (University of Southampton) do not necessarily represent the views or policy Thomas Hudson (University of Warwick) of the Editorial Team or London Mathematical Stephen Huggett (University of Plymouth) Society. Adam Johansen (University of Warwick) Bill Lionheart (University of Manchester) ISSN: 2516-3841 (Print) Mark McCartney (Ulster University) ISSN: 2516-385X (Online) Kitty Meeks (University of Glasgow) DOI: 10.1112/NLMS Vicky Neale (University of Oxford) Susan Oakes (London Mathematical Society) David Singerman (University of Southampton) Andrew Wade (Durham University) NEWSLETTER WEBSITE The Newsletter is freely available electronically Early Career Content Editor: Vicky Neale at lms.ac.uk/publications/lms-newsletter. News Editor: Susan Oakes Reviews Editor: Mark McCartney MEMBERSHIP CORRESPONDENTS AND STAFF Joining the LMS is a straightforward process. -

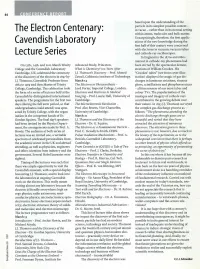

Cavendish Laboratory Lecture Series

44 CONFERENCE REPORT based upon the understanding of the particle in its simplest possible context - The Electron Centenary: in vacuo - rather than in its normal setting within atoms, molecules and bulk matter. Unsurprisingly, therefore, the first applic Cavendish Laboratory ations of the new knowledge during the first half of this century were concerned with electrons in vacuum: vacuum tubes Lecture Series and cathode-ray oscilloscopes. In England in the 1870s and 1880s interest in cathode-ray phenomena had On 13th., 14th. and 21st. March Trinity Advanced Study, Princeton. been stirred by the spectacular demon College and the Cavendish Laboratory What is Chemistry? 100 Years After strations of William Crookes. His Cambridge, UK, celebrated the centenary J.J. Thomson’s Discovery - Prof. Ahmed “Crookes’ tubes” (see front cover illus of the discovery of the electron in 1897 by Zewail, California Institute of Technology. tration) displayed the magic of gas dis J.J. Thomson, Cavendish Professor from March 14 charges in luminous striations, sinuous 1884 to 1919 and then Master of Trinity The Electron in Photosynthesis - glows, scintillations and phosphorescences College, Cambridge. The celebration took Lord Porter, Imperial College, London. - all forerunners of our neon tubes and the form of a series of lectures held at the Electrons and Positrons in Medical colour TVs. The popularisation of the Cavendish by distinguished international Imaging - Prof. Laurie Hall, University of mystique and imagery of cathode rays speakers. The programme for the first two Cambridge. contributed to the growing debate over days (during the full term period, so that The Microelectronic Revolution - their nature. In 1893 J.J. -

Contributions of Civilizations to International Prizes

CONTRIBUTIONS OF CIVILIZATIONS TO INTERNATIONAL PRIZES Split of Nobel prizes and Fields medals by civilization : PHYSICS .......................................................................................................................................................................... 1 CHEMISTRY .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 PHYSIOLOGY / MEDECINE .............................................................................................................................................. 3 LITERATURE ................................................................................................................................................................... 4 ECONOMY ...................................................................................................................................................................... 5 MATHEMATICS (Fields) .................................................................................................................................................. 5 PHYSICS Occidental / Judeo-christian (198) Alekseï Abrikossov / Zhores Alferov / Hannes Alfvén / Eric Allin Cornell / Luis Walter Alvarez / Carl David Anderson / Philip Warren Anderson / EdWard Victor Appleton / ArthUr Ashkin / John Bardeen / Barry C. Barish / Nikolay Basov / Henri BecqUerel / Johannes Georg Bednorz / Hans Bethe / Gerd Binnig / Patrick Blackett / Felix Bloch / Nicolaas Bloembergen