Main | Other Chinese Web Sites Chinese Cultural Studies: Concise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Williams Collection

Crystals are the flowers of the Mineral Kingdom THE MINERAL NEWSLETTER VOLUME 52 NO. 6 JUNE 2011 Also find information on our Club Website: Williams Collection http://www.novamineralclub.org By Sue Marcus ries behind this collection and Join us on June 27 for a glimpse of enjoy the landscapes of the English NVMC Schedule: the fabulous Williams Mineral Col- West Country as Sue takes us on a lection. Amassed by the family that vicarious journey. June 27 Gen. mtg. at Long owned the famous tin mines of Corn- Want to gather at the Olive Garden Branch Nature Center, 7:45pm wall, England, the collection was for dinner before the meeting featured at the 2011 Tuscon Mineral (dinner and a show!)? Call Sue Mar- 02 July - Field Trip - see page 5 Show. Thanks to club member Ruth cus at 703-502-9844 so she can make Goen, Sue Marcus and her husband the reservations for us. ** NOTE THIS CHANGE** Roger Haskins had the good fortune September 26+ AUCTION to have a private and personal tour Our meeting will start at 7:45pm at of the collection at its home in Caer- Long Branch Nature Center in Ar- October 24 Gen. Mtg. hays Castle. Some of the world's lington. November 28 Gen. mtg. best-in-species were rediscovered Guests are always welcome, as well December 19* here and the curator also wrote a as prospective new members. Show Holiday Meeting feature article it the latest Minera- and tell specimens are also encour- * This is a joint meeting logical Record. Come share the sto- aged. -

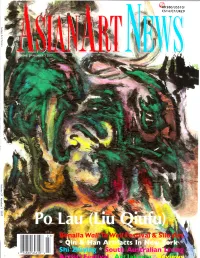

Robert C. Morgan

@,rro,ur'0, c$',4/€7luKf9 iri {:lrJ lian The Pusf Becorutes Preserut Tbe artifacts tlrat make up ttt)o recent major exhibitions of the Qin and Han dynasties remind us of tbe linked bistorical bumanity in our quotidian experience. Tbe exbibitions empbasize iust bottt releuant real lsuman contact is in truly understanding otber people omd cultures. 'tt,1. ; -:li :_*:r kr,,, :::""; Earthenware dancing figurine, Western Han (206 BC - AD 8), H.45 cm, W.42 cm. Excavated from the Tomb of King of Chu at Tuolanshan, Xuzhou (2000). 54 ASIAN ART NEWS voume2T Number 3 2OlZ ost Vie\vefs \\'ho attenclecl Sl-raanxi province. In short, the exhibi- nlsccnt ancl energetic socill ertvironntcnt tlrc lclut ivt'11' r'orttprelrcnsivt. ti(n pr'()\'okecl unexpc'ctecl possibilities irr n'hich Chinese people n,ele cor-ning exl.rihition. Age c1l' F.ntpires. fbr' \Westelncls to c()nlc t() tenls rritl'r tl're into tlteir'on,r-r, Chittese Art o.l' the Qitt € histolicll basis lncl cultr,rral essimiletion N()t ()nh: n'as it a ple'lsLre to see Hcrtt D1'rtcrsties (221 BC- AD of these <;bjects. Rather than clismiss these beatrtiftrlh' clisplayecl carthenr,vare 220),ttvere ostensibly movecl ir-r lln Llnsus- ing these sorks as xrt-f()r-xl'trj sakc. atr- ()l)jects. l>ut also t<> take n()tice of thcir pectirlg way. The sheer elegancc cntanlrt- cliences appcalc'cl to gr.rsp some of tlte conclitkrr-r. 'fhe vust majolity of nolks in ir-rg fi<>r-r-r these multivalent rvolks significcl corrplexitv ancl clensifi' of China tirm lrn this shon coulcl bc callecl objects that hacl the plesence of cver')rcla]' lif'e ls trn intc- engle <>f i.ision thel' hacl lulcly enc()Lul- n()t sccn the light of clay for centulies gral part of a pelennial uncl ernelgent cr,rl- terccl pleviousll'. -

THE EVOLUTION of CHINESE JADE CARVING CRAFTSMANSHIP Mingying Wang and Guanghai Shi

FEATURE ARTICLES THE EVOLUTION OF CHINESE JADE CARVING CRAFTSMANSHIP Mingying Wang and Guanghai Shi Craftsmanship is a key element in Chinese jade carving art. In recent decades, the rapid development of tools has led to numerous changes in carving technology. Scholars are increasingly focusing on the carving craft in addition to ancient designs. Five periods have previously been defined according to the evolution of tools and craftsmanship, and the representative innovations of each period are summarized in this article. Nearly 2,500 contemporary works are analyzed statistically, showing that piercing and Qiaose, a technique to take artistic advantage of jade’s naturally uneven color, are the most commonly used methods. Current mainstream tech- niques used in China’s jade carving industry include manual carving, computer numerical control engraving, and 3D replicate engraving. With a rich heritage and ongoing innovation in jade craftsmanship, as well as in- creased automation, the cultural value and creative designs are both expected to reach new heights. ade carving is one of the oldest and most impor- tools. In 1978, China opened its economy to the out- tant art forms in China, a craft steeped in history side. With the support of the government, influenced Jand tradition that reflects Chinese philosophy and by jade merchants and carvers from Taiwan and culture (Thomas and Lee, 1986). Carving, called Hong Kong and driven by an expanded domestic con- Zhuo and Zhuo mo in Chinese, represents the ardu- sumer market, China’s modern jade carving industry ous process of shaping and decorating an intractable has seen a period of vigorous development. -

A Jade Suit for Eternity Treasures of the Han Dynasty from Xuzhou May 25 – November 12, 2017

For Immediate Release China Institute Gallery Presents Dreams of the Kings: A Jade Suit for Eternity Treasures of the Han Dynasty from Xuzhou May 25 – November 12, 2017 Part of the Jade Suit of the King of Chu Kingdom (ca. 175 BCE) Photo courtesy of Xuzhou Museum NEW YORK – A rare shroud of precious stones designed to protect and glorify a king in the afterlife will be on view at China Institute Gallery’s new exhibition, Dreams of the Kings: A Jade Suit for Eternity, Treasures of the Han Dynasty from Xuzhou from May 25 – November 12, 2017. More than 76 objects originating from royal tombs dating from the Western Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 8 CE) will be exhibited in the U.S. for the first time. Ranging from terracotta performers to carved stone animal sculptures, the objects are extraordinary testimony to customs and beliefs surrounding life and death during the Western Han Dynasty, one of China’s golden eras. The exhibition is accompanied by a fully illustrated bilingual catalogue. In 201 BCE, the first emperor of the Han Dynasty knighted his younger brother as the first king of the Chu Kingdom, which was centered in Peng Cheng, today’s Xuzhou, in northern Jiangsu Province. Ruling under the emperor’s protection, and given special exemption from imperial taxes, elites in this Kingdom enjoyed a lavish lifestyle. Twelve generations of kings lived, died, and were buried in sumptuous tombs carved into the nearby rocky hills. Although many of the tombs were looted over the years, numerous treasures were discovered in later excavations testifying to the Chu kings’ affluence as well as their beliefs in immortality and the afterlife. -

Coffin Soul Portals of the Female Xunren in Tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng" (2020)

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations August 2020 Coffin Soul Portals of the Female Xunren in Tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng Mary E. Blum University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Asian History Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Blum, Mary E., "Coffin Soul Portals of the Female Xunren in Tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng" (2020). Theses and Dissertations. 2462. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/2462 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COFFIN SOUL PORTALS OF THE FEMALE XUNREN IN TOMB OF MARQUIS YI OF ZENG by Mary E. Blum A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art History at The University of Wisconsin Milwaukee August 2020 ABSTRACT COFFIN SOUL PORTALS OF THE FEMALE XUNREN IN TOMB OF MARQUIS YI OF ZENG by Mary E. Blum The University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, 2020 Under the Supervision of Professor Ying Wang There is a significant void in scholarship concerning the Tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng’s (Zeng Hou Yi), Leigudun M1, Suizhou, Hubei Province, dated to 433 BCE during the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (770-256 BCE) of Bronze Age China, specifically on the lacquer coffins of the female xunren. -

China Institute Gallery Presents Dreams of the Kings: a Jade Suit for Eternity Treasures of the Han Dynasty from Xuzhou May 25 – November 12, 2017

For Immediate Release China Institute Gallery Presents Dreams of the Kings: A Jade Suit for Eternity Treasures of the Han Dynasty from Xuzhou May 25 – November 12, 2017 Part of the Jade Suit of the King of Chu Kingdom (ca. 175 BCE) Photo courtesy of Xuzhou Museum NEW YORK – A rare shroud of precious stones designed to protect and glorify a king in the afterlife will be on view at China Institute Gallery’s new exhibition, Dreams of the Kings: A Jade Suit for Eternity, Treasures of the Han Dynasty from Xuzhou from May 25 – November 12, 2017. More than 76 objects originating from royal tombs dating from the Western Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 8 CE) will be exhibited in the U.S. for the first time. Ranging from terracotta performers to carved stone animal sculptures, the objects are extraordinary testimony to customs and beliefs surrounding life and death during the Western Han Dynasty, one of China’s golden eras. The exhibition is accompanied by a fully illustrated bilingual catalogue. In 201 BCE, the first emperor of the Han Dynasty knighted his younger brother as the first king of the Chu Kingdom, which was centered in Peng Cheng, today’s Xuzhou, in northern Jiangsu Province. Ruling under the emperor’s protection, and given special exemption from imperial taxes, elites in this Kingdom enjoyed a lavish lifestyle. Twelve generations of kings lived, died, and were buried in sumptuous tombs carved into the nearby rocky hills. Although many of the tombs were looted over the years, numerous treasures were discovered in later excavations testifying to the Chu kings’ affluence as well as their beliefs in immortality and the afterlife. -

Download Article

International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2016) On Relation between Sheep Horn Bell and Ancient Guangxi Musical Culture Zhian Bie Normal College Nanyang Institute of Technology Nanyang, China Abstract—The Sheep Horn-bell was a representative symbol was the development of special local bronze culture; in implement in bronze culture in southeast area in ancient China, late Qin and early Han, Qin general Zhao Tuo built Nanyue an old national musical instrument and sacrificial vessel rich in state, to which most part of Guangxi belonged, speeding up the local features. It can be seen from the unearthing range and civilization of Guangxi; up to the reign of Emperor Wu of Han, number that the Sheep Horn-bell was a representative ritual and as the power of the Central Plains went southward, Guangxi music object in Luoyue nationality in ancient Guangxi, and we entered the feudal society, and the mainstream culture was also can understand its special status in Luoyue nationality by unified into the great Chinese system; after Wei and Jin observing it and other contemporary bronze musical instrument. Dynasties, ancient tribe of Guangxi gradually developed to Keywords—sheep horn bell; bronze culture; Guangxi; music abundant minority tribes as it is today. Thus, the history of of Luoyue nationality music culture of Guangxi in ancient times had a certain relation to music culture of the Central Plains and Chu area, but it presented different styles and features more. In brief, I. INTRODUCTION effected by the rite and music culture of the Central Plains and The Sheep Horn-bell was a representative implement in Chu area, and in the communication with kingdoms of Yue bronze culture in southeast area in ancient China, an old nationality in southwest area which developed to kingdom national musical instrument and sacrificial vessel rich in local culture along with the western area, ancestors of Zhuang features. -

The Bi Disc Imagery in the Han Burial Context

DOI: 10.4312/as.2019.7.2.115-151 115 Representation of Heaven and Beyond: The Bi Disc Imagery in the Han Burial Context ∗ Hau-ling Eileen LAM 8 Abstract The bi (“disc”) is an object that was originally made from jade, and became an inde- pendent motif that appeared widely in different pictorial materials during Han times. The bi disc is considered one of the earliest jade forms, and has been used for ritual purposes or as an ornament from the Neolithic period until today. This paper focuses on the Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE), a period in which jade bi discs were exten- sively used and placed in burials of different ranks. Present finds show that images of bi discs also appeared widely in Han burials, in which they were depicted on cof- fins, funerary banners covering coffins, and mural paintings, and were also engraved on pictorial stones and pictorial bricks, these practices becoming more ubiquitous in the later Han period. By studying various images of bi discs in different burials throughout the Han period, this paper will explore the development and significance of different pictorial representations ofbi disc in Han burial context, and also attempt to reveal the rich content and thoughts embedded in the form of bi discs during this period of time. Keywords: bi disc, imagery, pictorial representation, heaven, Han Dynasty Upodobitev Neba: podoba diska bi v grobnem kontekstu dinastije Han Izvleček Bi (»disk«) je predmet, ki je bil prvotno narejen iz žada, pozneje je postal samostojen motiv ter se je pogosto pojavljal v različnih slikovnih podobah v času dinastije Han (202 pr. -

Scholar's Studio

HANSHAN TANG BOOKS • L IST 143 NEW PUBLICATIONS SCHOLAR ’S STUDIO LATEST ACQUISITIONS H ANSHAN TANG B OOKS LTD Unit 3, Ashburton Centre 276 Cortis Road London SW 15 3 AY UK Tel (020) 8788 4464 Fax (020) 8780 1565 Int’l (+44 20) [email protected] www.hanshan.com CONTENTS N EW & R ECENT P UBLICATIONS / 3 S CHOLAR ’ S S TUDIO / 22 F ROM O UR S TOCK / 32 S UBJECT I NDEX / 64 T ERMS The books advertised in this list are antiquarian, second-hand or new publications. All books listed are in mint or good condition unless otherwise stated. If an out-of-print book listed here has already been sold, we will keep a record of your order and, when we acquire another copy, we will offer it to you. If a book is in print but not immediately available, it will be sent when new stock arrives. We will inform you when a book is not available. Prices take account of condition; they are net and exclude postage. Please note that we have occasional problems with publishers increasing the prices of books on the actual date of publication or supply. For secondhand items, we set the prices in this list. However, for new books we must reluctantly reserve the right to alter our advertised prices in line with any suppliers’ increases. P OSTAL C HARGES & D ISPATCH United Kingdom: For books weighing over 700 grams, minimum postage within the UK is GB £6.50, except for ‘Home Delivery UK’ (24 hrs) which costs £7.50 minimum. -

Copyright © 2009 by Berkshire Publishing Group LLC

Copyright © 2009 by Berkshire Publishing Group LLC H ◀ G HAI Rui Hǎi Ruì 海 瑞 1514–1587 Ming dynasty official Hai Rui 海瑞 (1514–1587) was a scholar and bu- and shaming prominent figures who sought special treat- reaucrat who served in the late Ming Dynasty ment in his jurisdiction. (1368– 1644). He was known for his stern ethi- Hai was soon promoted to a minor post in the Min- cal positions and his unswerving rectitude, re- istry of Revenue at the capital. In 1565, Hai got into trou- ble for writing a scathing admonition to the emperor, maining an icon of political incorruptibility attacking his personal morals, accusing him of misrule, for the rest of Chinese history. and urging him to reform his ways. For Hai’s lese- majeste (crime committed against a sovereign power) he was imprisoned and only narrowly escaped execution. After ai Rui was a civil official of the late Ming dynasty his release Hai Rui continued to be appointed to promi- (1368– 1644), famous for his uncompromising nent positions in the bureaucracy, although he was given moral stance and his Spartan lifestyle. In an mostly sinecure positions that limited the reach of his era when civil servants commonly enriched themselves stern moralism. through their official positions, Hai was hailed as a para- In 1569, after begging the emperor to give him a gon of the idealistic Confucian values of incorruptible more substantial position, Hai was assigned to the post service to the people and the state. According to his offi- of governor of the Southern Metropolitan District, the cial biography, he was so frugal that his purchase of some prosperous region around Suzhou and Nanjing. -

August 2009 an All-American Club Santa Clara Valley Gem and Mineral Society San Jose, California

Breccia Volume 56, Number 8 August 2009 An All-American Club Santa Clara Valley Gem and Mineral Society San Jose, California Randy says… the Cabana Club. Please bring your favorite Hello Fellow Rockhounds, main dish, side dish, salad, or dessert to share. You will notice as you read this month’s issue I hope everyone is having a great summer. that we are drawing near to election time again. Please give serious consideration to how you Randy Harris, President would like to be involved in the workings of the club. Then fill out the Time and Talent sheet and turn it in to one of the officers by the September Member Displays: AUGUST meeting. This is how we determine who to nominate for office and committee positions. If This is a favorite part of our general you are unsure about the jobs, talk to the person meetings. Your scheduled date is a suggestion; doing the job now for some insight. For some of you can display any time you wish. This list is the newer members, there are several jobs that alphabetical by last name. are not very difficult and would be a good way to learn more about how the club operates. This is If your last name begins with your club, it does not work without your help. Q, R, S or T, itʼs your turn! ★ Nominations for officers are coming up in October. The election will be held at the November meeting. Welcome, New Members The Board has reserved the Cabana Club for our annual Installation Dinner. -

Early Chinese Lead-Barium Glass Its Production And

Early Chinese Lead-Barium Glass Its Production and Use from the Warring States to Han Periods (475 BCE-220 CE) Christopher F. Kim ARCH0305 Prof. Carolyn Swan May 7, 2012 K i m | 2 1. INTRODUCTION Research on early Chinese glassmaking is a relatively recent endeavor only properly begun within the last fifty years. Pioneering studies were conducted in the 1930s but the field lay dormant until the 1950s and 1960s, at which time numerous archaeological excavations in China provided scholars with more material to work with (Brill and Martin 1991:vii).1 Even then, research on early Chinese glass was primarily led by scientists; in 1982, Robert Brill was only able to locate three Chinese scholars ―who had more than a passing interest in early Chinese glass‖ (Brill and Martin 1991:viii). Since then, however, the field has grown steadily in large part due to further advances in chemical analysis techniques and growing interest on the topic. At present, it is accepted that in China,2 glassmaking began around the 5th century BCE during the late Spring and Autumn to early Warring States periods (see Fig 1.1 for a timeline of early Chinese history). Chemical analyses of glass samples dating to this time have identified no less than three glass systems: potash-lime, lead-barium, and potash;3 of these, lead-barium was the most significant in early China, and is therefore the primary focus of the present study.4 Despite considerable advances in the study of Chinese glass, a number of critical issues are still unclear and fiercely debated: (1) Many scholars argue that Chinese glassmaking derived directly from Western glassmaking, and so is not an independent innovation, and (2) the comparative lack of glass objects, particularly glass vessels, relative to those of bronze, ceramic, 1 Especially significant was Beck, Seligman, and Ritchie‘s 1934 article which first identified early Chinese glass as containing large amounts of lead and barium (Gan 1991:1).