Netherlands Phase 4 Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Possibilities for Early Contractor Involvement in Infrastructure Projects in the Netherlands

2014 Possibilities for early contractor involvement in infrastructure projects in the Netherlands C.C. van Huuksloot 4002547 30-5-2014 0 PROJECT DETAILS Master thesis project: Possibilities for early contractor involvement in infrastructure projects in the Netherlands. PERSONAL DETAILS Author: Carmen Cecilia van Huuksloot Student number: 4002547 Telephone number: +31 623493392 Email address: [email protected] STUDY PROGRAM Study program: Construction management & engineering Graduation department: Building processes Faculty: Civil engineering University: Delft University of Technology GRADUATION COMMITTEE TU Delft Chairman: Prof. Dr. ir. M.J.C.M. Hertogh First supervisor: Ir.L.P.I.M. Hombergen Second supervisor: Dr. W.M. de Jong Ballast Nedam Content supervisor: Ir. C.Q. Klap General supervisor: E. Aal GRADUATION ORGANIZATION Ballast Nedam Infra Special Projects Ringwade 71 3439 LM Nieuwegein Tel: +31 30 285 30 60 1 Preface My name is Carmen van Huuksloot and I am a master student Construction Management and Engineering at the faculty of Civil Engineering at the Technical University in Delft. This report is written as part of my graduation research to the possibilities for early contractor involvement in infrastructure projects in the Netherlands. During my study I have always been interested in the procurement of major infrastructure projects and thus I was sure that I wanted to use this subject for my graduation research. Nowadays there are many different opinions on the tender procedure in the Netherlands, dependent on the interests of different parties. In addition, there are different approaches to procurement. Every time, something new is introduced to meet the needs of all stakeholders. There was the option to look at existing approaches, but to me it was more challenging to explore something for my graduation research that is uncharted territory in the Netherlands. -

1.2 Motivation for This Master's Thesis

Design for the in- and outlet structure of the Energy Storage Lake within the Delta21 plan Yordi Paasman 4221346 B.Sc. in Civil Engineering, Delft University of Technology, 2017 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science To be presented publicly on Friday March 13th, 2020 at 15:30h. Thesis committee: Dr. ir. M. A. N. Hendriks TU Delft, supervisor Ir. L. J. M. Houben TU Delft Dr. ing. M. Z. Voorendt TU Delft Ing. G. F. van der Woerdt, MBA Ballast Nedam Structural Engineering Hydraulic Structures Delft University of Technology The Netherlands An electronic version of this thesis is available at http://repository.tudelft.nl/. ABSTRACT Yordi Paasman, Structural Engineering, University of Technology Delft Abstract of Master’s Thesis, Submitted 05 March 2020: Design for the In- and Outlet Structure of the Energy Storage Lake within the Delta21 Plan. This thesis aims to come up with a preliminary design for the in- and outlet structure, in which pump-turbines are housed, of the energy storage lake within the Delta21 plan. The goal is to come up with a feasible, cost-effective and lasting solution, that can store green energy, pump out 10 000 m3/s of water and retain design storms, the classic design steps are followed. The method followed, starts with an analysis of the problem, giving insight to the relevant stakeholders and functions that should be included. These elements lead to the Program of Requirements, which contains research into the tailor-made pump-turbine sys- tem and present-day water levels. -

Smart Stadium Tools

Smart Stadium Tools An explorative case study of the Johan Cruijff ArenA: identification and optimization of smart tools Simon van Heck | Master Thesis | June 2019 | Delft University of Technology This page is intentionally left blank - 2 - Integrating Smart Tools within Stadiums An explorative case study of the Johan Cruijff ArenA: identification and optimization of smart tools by Simon Gerard Janus van Heck in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Management in the Built Environment at the Delft University of Technology COLOPHON Details Student number 4289986 Graduation Lab (Public) Real Estate Management Graduation Company KPMG The Netherlands Project duration February, 2019- July, 2019 Version P5-report Date June 18, 2019 Graduation committee 1st mentor Prof.dr.ir. A. (Alexandra) Den Heijer, Full professor Public Real Estate, TU Delft 2nd mentor Drs P.W. (Philip) Koppels, TU Delft, 2nd supervisor Assistant professor Real Estate Management, TU Delft 3rd mentor Ir. B. (Bart) Valks, TU Delft, 3rd supervisor PhD researcher Smart campus tools, TU Delft Company supervisor Ir. W. (Wilco) Leenslag, KPMG Innovation Advisory, company supervisor Senior manager KPMG Innovation Advisory Delegate examiner Ir. S. (Steven) Steenbruggen, TU Delft - 3 - Preface In the context of my Master of Science in Management in the Built Environment (MBE) at the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment at the Delft University of Technology, I conducted this research as my final graduation project. The research focused on improving the integration of smart tools in stadiums, which fits in the department of real estate management. This research is the results of almost nine months of work. -

2020 Annual Report

2 of 136 3 of 136 4 of 136 5 of 136 Table of contents Report of the Board of Management Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................... 8 1. Profile of Ballast Nedam ................................................................................................................................................ 11 1.1 Who we are ........................................................................................................................................................... 13 1.2 What we do ............................................................................................................................................................ 15 1.3 How we do it .......................................................................................................................................................... 16 1.4 Our stakeholders ................................................................................................................................................... 17 1.5 Market trends ......................................................................................................................................................... 19 2. Business Review ............................................................................................................................................................ 23 2.1 Overview of 2020 .................................................................................................................................................. -

International Journal on Public Works, Ports & Waterways Developments

International Journal on Public Works, Ports & Waterways Developments Number 80 • September 2000 International Association of Dredging Companies Terra et Aqua – Number 80 – September 2000 Terra et Aqua is published quarterly by the IADC, The International Association of Dredging Companies. The journal is available on request to individuals or organisations with a professional interest in the development of ports and waterways, and in particular, the associated dredging work. The name Terra et Aqua is a registered trademark. Editor Marsha R. Cohen Editorial Advisory Committee H.A.J. Fiers, Chairman H. van Diepen H. De Vlieger H.W.J. Poiesz K. de Groot R. Vidal Martin P.G. Roland P.J.A. Hamburger F.A. Minderhoud H. Cami IADC Board of Directors R. van Gelder, President O. Nakagome, Vice President C. van Meerbeeck, Treasurer P.G. Roland M. Montevecchi G. Vandewalle D. Eicke J.J. Koeman Please address inquiries to the editor. Articles in Terra et Aqua do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the IADC Board or of individual members. © 2000 IADC, The Netherlands All rights reserved. Electronic storage, reprinting or abstracting of the contents is allowed for non-commercial purposes with permission of the publisher. ISSN 0376-6411 Typesetting and printing by Opmeer Drukkerij bv, The Hague, The Netherlands. Front cover: The construction of the container terminal at Pelabuhan Tanjung Pelepas, Malaysia is part of one of the world’s most intensive dredging and land reclamation projects (see page 3). IADC P.J.A. Hamburger, Secretary General Duinweg 21 2585 JV The Hague, The Netherlands Tel. 31 (70) 352 3334, Fax 31 (70) 351 2654 E-mail: [email protected] International Association of Dredging Companies http://www.iadc-dredging.com Terra et Aqua – Number 80 – September 2000 CONTENTS 2 Editorial 3 Tanjung Pelepas Port: From Jungle to Malaysia’s Newest Container Port Allard Renkema and David Kinlan Working on a fast track, in less than 5 years, a quiet oil palm plantation area has been transformed into an active port and industrial area. -

Netherlands Economic Mission to Ireland

Netherlands Economic Mission to Ireland 13 - 14 June 2019 Netherlands Economic Mission to Ireland 13 - 14 June 2019 3 5 Index The Netherlands Foreword Minister Sigrid Kaag 8 Foreword Jacco Vonhof 9 Map of the Netherlands 13 Introducing the Netherlands 14 Ireland and the Netherlands 16 Company Profiles Alt4 & CTVrede 20 Ballast Nedam 21 BAM Infraconsult 22 CERTUS Port Automation 23 Damen Shipyards 24 Deltares 25 Dieseko Group 26 Fotolight / Construction&Display 27 Geba Trans 28 KVSA 29 MEP 30 MKB-Nederland 31 Netherlands Water Partnership 32 North Sea Port Netherlands 33 Port of Amsterdam International 34 Port of Rotterdam 35 Royal Boskalis Westminster 36 Strukton 37 TMA Logistics 38 Van den Herik 39 Van Oord Dredging and Marine Contractors 40 Official Delegation Ministry of Foreign Affairs 44 Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Dublin 45 Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy | Netherlands Enterprise Agency 46 6 7 Foreword Foreword Ireland and the Netherlands have enjoyed strong As the President of the Royal Association for Small and political and economic relations for many decades. Medium Enterprises, it is my great honour to introduce As maritime nations and members of the European myself to you, as the business leader of the Economic Union, we are outward-looking countries with common Mission to Ireland together with Minister Sigrid Kaag, interests and challenges when it comes to trade, which conincides with the State Visit of Their Majesties maritime infrastructure, connectivity and climate King Willem-Alexander and Queen Máxima. change. So port and maritime development are natural priorities for both our countries. -

Annual Report 2013

Schiphol Group Annual Report 2013 Contents Contents About us 2 Profile 3 Facts and Figures 6 Aviation Mission and Ambition 8 page 14 Schiphol constructs, converts and connects 10 Business model 13 Strategy 22 Message from the CEO 23 Consumer Changing business environment 25 Strategy 28 Products & Management Agenda 2014 31 Services page 16 Our results for 2013 32 Management Agenda 2013 33 Top Connectivity 34 Real Estate Excellent Visit Value 44 page 18 Competitive Marketplace 53 Sustainable Performance 59 Economic regulation 79 Financial performance 81 Governance 85 Alliances & Report of the Supervisory Board 86 Participations Supervisory Board 94 page 20 Management Board 96 Corporate Governance 99 Remuneration 102 Shareholder information 107 Risk management 108 Annual Statements Operational and socio-economic statements 115 Financial Statements 2013 132 2013 Annual Report 1 About us 2013 Annual Report 2 Profile Profile Schiphol Group is an airport company and Amsterdam Airport Schiphol is its principal airport. We aim to create sustainable value for our stakeholders, with due regard for their various interests. All our actions reflect our key values: reliability, efficiency, hospitality, inspiration and sustainability. Destinations hub The activities at Schiphol are an important engine that drives Amsterdam Airport Schiphol is a well-equipped international the Dutch economy and generates employment. Every year, airport that offers state-of-the-art facilities to 99 airlines aviation adds over 26 billion euros to the Dutch gross domestic which, in 2013, carried a total of 52.6 million travellers and product. The Schiphol site alone accommodates some five over 1.5 million tonnes of cargo from Schiphol to destinations hundred companies that provide jobs for approximately all over the world. -

View Volume 8, Issue 1

View is the client magazine of BAM International bv – Volume 8, Issue 1 - 2017 View New project in Antarctica Creating the future in Dubai Tunnel to sustainability BAM International is an operating company of Royal BAM Group, one of Fast and eco-friendly Europe’s largest contracting companies EDF’s Blyth offshore wind demonstration active in construction, property, civil project will debut the gravity base engineering, public-private partnerships, foundation for offshore wind turbines. mechanical and electrical contracting, By mid-2017 these five innovative consultancy and engineering in foundations will sit on the North Sea 30 countries across the globe. bottom, off the Northumberland coast BAM International operates outside Europe. in the United Kingdom, each carrying a 10-metre high turbine with a capacity The BAM acronym is included in the of 8.3 megawatts. Construction of the names of all our subsidiaries and joint caissons took place in the Newcastle ventures to indicate that in all our Yard. Measuring 30 metres in diameter, activities we benefit from the collective these concrete artefacts will float on strength, know-how and experience of the water till they are moved into place, entire Royal BAM Group. ballasted and immersed. In today’s competitive market our goal is to exceed clients’ expectations, deliver on time and on budget and at the same time act sustainably and contribute positively View inside to the communities where we work. 4 Attractive proposals for our clients Address BAM House The Hague 6 The impact of being an -

Water and the Dutch

SWEET & SALT Water and the Dutch NAi Publishers Tracy Metz & Maartje van den Heuvel 5 Introduction 6 Water in Pictures 13 From Seascapes to VJ Art Sweet, Salt and Saline 22 Conflict 44 Dikes and Polders 74 Concord 96 Big Water 122 Profit 144 Wet City 172 Pleasure 196 Catastrophe 224 Myth 246 Water and the Dutch 280 Bibliography 288 INLEIDING / 7 INTRODUCTION / 9 No element is as intrinsic to the Dutch cultural being given room (a friend). Polders are being identity as water. A look at maps of the Nether- allowed to flood, dams are being opened, resi- lands spread over the centuries is enough to dential developments are being built in and realize how defining water is for this delta. on the water, dikes and dunes are being slot- When a storm surge hits, the Dutch watch ted into each other, rivers are being widened. anxiously to see whether the rivers are going to Engineers and designers are learning each overflow their banks again. They handle water other’s language, and creativity in relation to ingeniously and with great know-how when water is getting a new impetus. they want to control, repel or guide it. They use For Tracy Metz, born in the USA and a resi- it for profit, at sea or in the port that is the link dent of the Netherlands for over half her life, between the maritime world and the economy her travels around the ‘water world’ provided a in the hinterlands. They enjoy the beauty of fascinating look at the making, and the ‘make- water and can derive intense pleasure from ability’, of the Dutch landscape. -

Annual Report 2016 Ballast Nedam

Annual Report 2016 Ballast Nedam Table of contents Report of the Board of Management Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 3 1 Profile of Ballast Nedam .................................................................................................................. 4 Vision, mission and values ...................................................................................................... 4 Core activities and organizational structure ............................................................................ 5 Composition of the Board of Management .............................................................................. 6 Responsibility Statement of the Board of Management .......................................................... 7 2 Strategy ........................................................................................................................................... 8 Overview of 2016 ..................................................................................................................... 8 Financial results ....................................................................................................................... 9 Outlook for 2017 .................................................................................................................... 11 3 Risk and risk management ........................................................................................................... -

Projectorganisatie Stormvloedkering 1987?

25 26 \ \ 1UW \ ^^ •11 • - \ \ !^i jÊiVv \ 7* "•«•» t 4 w \ A\ -| t i ï ' <**^^ 4ii« """" i •.' • . 1 .•' -" ' 7 ft 1 \ > \ •™~— * —i » • I E^B^ A* « f- 27 28 29 30 31 Boek 1:Totaalontwerp en ontwerpfilosofie Deelnota 1 Totaalontwerp Deelnota 2 Ontwerpfilosofie Deelnota 3 Natuurrandvoorwaarden Deelnota 4 Beschrijving van het ontwerp Deelnota 5 Beheer, bewaking en onderhoud 32 Deelnota 1: Totaalontwerp 33 34 Inhoud 1. Inleiding 1.1. Doel van de nota 1.2. Indeling van de nota 1.3. Totstandkoming van de nota 1.4. Opslag documentatie 2. Het project In een breder verband 2.1. Kort historisch overzicht 2.2. De betekenis van het project voor Zuidwest-Nederland 3. Randvoorwaarden voor de stormvloedkering 3.1. Doorstroomopening 3.2. Veiligheid (kerende hoogte) 3.3. Overige randvoorwaarden 4. Ontwikkeling van het ontwerp 4.1. Inleiding 4.2. Van tijdelijke doorlaatbare blokkendam tot permanente pij- lerdam 4.3. Van „pijlers op putten" naar „pijlers op staal,, 4.4. De ontwikkeling van het ontwerp voor de drempel en het funderingsbed 5. Organisatie van het project 5.1. Inleiding 5.2. De projectorganisatie voor de stormvloedkering 5.2.1. De totale opzet 5.2.2. Verdere uitwerking van de projectorganisatie 5.3. Contractuele aspecten 5.4. Relatie aspecten 5.5. Plannings aspecten 1. Inleiding 1.1. Doel van de Nota Reeds in een vroeg stadium van het ontwerp van de stormvloedke Aan de hierboven uitgezonderde onderwerpen zal in afzonderlijke ring werd de noodzaak onderkend van het verzamelen en zorgvul nota's uitgebreid aandacht worden besteed. dig bewaren van belangrijke gegevens die tot de totstandkoming van het ontwerp hebben bijgedragen. -

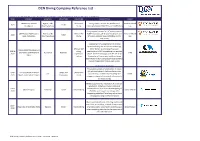

DCN Diving Company Reference List

DCN Diving Company Reference List Following are some selected projects but the list is not limited to (visit www.dcndiving.com/projects-map for more info): YEAR PROJECT LOCATION STRUCTURE DISCIPLINE DESCRIPTION CLIENT CBM PLEM Umbilical Nigeria, Lekki Offshore Air Diving support services for installation of Pinnacle Oil and 2020 PLEM Installation Free Trade Zone Diving umbilical between CBM PLEM and POWER Buoy Gas Diving support services for 16" pipelay support, CBM Pipelay PLEM Subsea Nigeria, Lekki Offshore Air PLEM instalaltion, 16" Z spool installation and Pinnacle Oil and 2020 PLEM Hose Installation Free Trade Zone Diving 12"subsea umbilical hose installation and As- Gas Built survey. Development of a patended Micro Habitat System including FAT and proven technology. Offshore SAT Diver Welder and Welding Procedure Micro Habitat Development 2020 & diving, qualifications in DCN's hyperbaric and wet test and Ninian South Platform NL and UK Platform CNRi 2020 Hyperbaric centre. Offshore campaign with the use of Sat Repair testing Diving where 4 brace repair welds on Ninian South Platform were completed including NDT at a depth ranging from 43msw and 76msw. Click here for more info The project consists of construction of eleven (11) artificial islands in Hail and Gasha fields, 2019- Hail and Ghasha Artificial Jettey and Offshore Air UAE Butinah Jetty, Butinah Centre Building and NMDC 2020 Islands Construction Project Breakwater Diving navigation channels that provide safe access to the these islands. Diving support for the installation of a new rail- way tunnel. Activities included removal of 2019- concrete barrier with Ultra-HP Waterjetting of Munich Airport Germany Tunnel Inshore Diving Ballast Nedam 2020 2500 Bar, underwater concreting, other supporting activities.