V1 4.16 Soils Geology Seismicity (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DEC Avalanche Preparedness in the Adirondacks Brochure (PDF)

BASIC AVALANCHE AWARENESS ADDITIONAL RESOURCES New York State Department of This brochure is designed to let the recreational Organizations Environmental Conservation user know that avalanche danger does exist in New York and gives basic ideas of what to look for U.S. Forest Service Avalanche Center PO Box 2356 and avoid. To learn more about avalanche Ketchum, Idaho, 83340 awareness consider attending professional Office Phone: (208) 622-0088 courses, reading and experience. www.fsavalanche.org Avalanche Westwide Avalanche Network Preparedness in the www.avalanche.org 1. Know basic avalanche rescue techniques. American Avalanche Association Adirondacks 2. Check the snow depth. www.avalanche.org/~aaap 3. Check how much new snow has fallen. Books 4. Practice safe route finding. Mountaineering: The Freedom of the Hills Published by The Mountaineer Books 5. Check the degree of the slope. Snow Sense: A Guide to Evaluating Snow Avalanche Hazard Published by Alaska Mountain Safety Center, Inc. 6. Check the terrain. 7. Carry basic avalanche rescue equipment. Thank You For Your 8. Never travel alone. Cooperation 9. Let someone know where you are going. NYSDEC - Region 5 Ray Brook, New York 12977 10. Do not be afraid to turn around. (518) 897-1200 Emergency Dispatch Number: (518) 891-0235 11. Use common sense. Visit the DEC Website at www.dec.ny.gov Photograph by: Ryland Loos Photograph by: Ryland Loos WHAT IS AN AVALANCHE? HOW CAN YOU KEEP FROM GETTING CAUGHT WHAT DO YOU DO WHEN CAUGHT IN AN IN AN AVALANCHE? AVALANCHE? An avalanche is a mass of snow sliding down a mountainside. Avalanches are also called You can reliably avoid avalanches by recognizing Surviving avalanches can depend on luck, but it is snowslides; there is no difference in these terms. -

The Politics of Information in Famine Early Warning A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Fixing Famine: The Politics of Information in Famine Early Warning A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Communication by Suzanne M. M. Burg Committee in Charge: Professor Robert B. Horwitz, Chair Professor Geoffrey C. Bowker Professor Ivan Evans Professor Gary Fields Professor Martha Lampland 2008 Copyright Suzanne M. M. Burg, 2008 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Suzanne M. M. Burg is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm: _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2008 iii DEDICATION For my past and my future Richard William Burg (1932-2007) and Emma Lucille Burg iv EPIGRAPH I am hungry, O my mother, I am thirsty, O my sister, Who knows my sufferings, Who knows about them, Except my belt! Amharic song v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………………. iii Dedication……………………………………………………………………….. iv Epigraph…………………………………………………………………………. v Table of Contents………………………………………………………………... vi List of Acronyms………………………………………………………………… viii List of Figures……………………………………………………………………. xi List of Tables…………………………………………………………………….. xii Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………….. xiii Vita………………………………………………………………………………. -

Investigating the El Capitan Rock Avalanche

BY GREG STOCK INVESTIGATING THE EL CapITAN ROCK AVALANCHE t 2:25 on the morning of March 26, 1872, one of avalanche, an especially large rockfall or rockslide that the largest earthquakes recorded in California extends far beyond the cliff where it originated. Most Ahistory struck along the Owens Valley fault near Yosemite Valley rockfall debris accumulates at the base the town of Lone Pine just east of the Sierra Nevada. The of the cliffs, forming a wedge-shaped deposit of talus. earthquake leveled most buildings in Lone Pine and sur- Occasionally, however, debris from a rock avalanche will rounding settlements, and killed 23 people. Although extend out much farther across the valley floor. seismographs weren’t yet available, the earthquake is esti- Geologist Gerald Wieczorek of the U.S. Geological mated to have been about a magnitude 7.5. Shock waves Survey and colleagues have identified at least five rock from the tembler radiated out across the Sierra Nevada. avalanche deposits in Yosemite Valley. The largest of these On that fateful morning, John Muir was sleeping in occurred in Tenaya Canyon, at the site of present-day a cabin near Black’s Hotel on the south side of Yosemite Mirror Lake. Sometime in the past, a rock formation on Valley, near present-day Swinging Bridge. The earth- the north wall of the canyon just east of and probably quake shook the naturalist out of bed. Realizing what similar in size to Washington Column collapsed into was happening, Muir bolted outside, feeling “both glad Tenaya Canyon. The rock debris piled up against the and frightened” and shouting “A noble earthquake!” He south canyon wall to a depth of over 100 feet. -

Controlled Avalanche – a Regulated Voluntary Exposure Approach for Addressing

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.12.20062687; this version posted April 22, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Controlled Avalanche – A Regulated Voluntary Exposure Approach for Addressing 2 Covid-19 ₤ 3 Eyal Klement1* DVM, Alon Klement2 SJD, David Chinitz3 PhD, Alon Harel4 Dphill, Eyal 4 Fattal5 PhD, Ziv Klausner5 PhD 5 6 1. Koret School of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Epidemiology and Public 7 Health, the Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel 8 2. Buchmann Faculty of Law, Tel-Aviv University, Israel 9 3. Department of Health Policy and Management, School of Public Health, Hebrew 10 University, Jerusalem, Israel 11 4. Phillip and Estelle Mizock Chair in Administrative and Criminal Law, The Faculty of 12 Law, the Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel 13 5. Department of Applied Mathematics, Israel Institute for Biological Research, Ness- 14 Ziona, Israel 15 ₤ 16 All authors contributed equally to the manuscript 17 18 * Corresponding author: 19 Address: Koret School of Veterinary Medicine, The Robert H. Smith Faculty of 20 Agriculture, Food and Environment, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, POB 12, 21 Rehovot 76100, Israel. 22 Tel: 972-8-9489560. Fax: 972-8-9489634 23 E-mail: [email protected] 24 25 NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.12.20062687; this version posted April 22, 2020. -

Avalanche Safety Tips

Submit Education Center | Photo Gallery Contents Avalanche Awareness: 1. Why avalanche awareness? Surviving an avalanche 2. Who gets caught in avalanches? A true account 3. When and where avalanches happen 4. Anatomy of an avalanche Avalanche Books 5. Avalanche factors: what conditions cause an avalanche? Credits & Citations 6. How to determine if the snowpack is safe 7. Avalanche gear For more information, see our 8. Tips for avalanche survival list of other avalanche sites 9. Avalanche danger scale 10. Avalanche quick checks 1. Why avalanche awareness? Mountains attract climbers, skiers and tourists who scramble up and down the slopes, hoping to conquer peaks, each in their own way. Yet, to do this they must enter the timeless haunt of avalanches. For centuries, mountain dwellers and travelers have had to reckon with the deadly forces of snowy torrents descending with lightning speed down mountainsides. Researchers and experts are making progress in detection, prevention and safety measures, but avalanches still take their deadly toll throughout the world. Each year, avalanches claim more than 150 lives worldwide, a number that has been increasing over the © Richard Armstrong past few decades. Thousands more are caught in avalanches, partly buried or injured. Everyone from An avalanche in motion. snowmobilers to skiers to highway motorists are (Photograph courtesy of caught in the "White Death." Most are fortunate Richard Armstrong, National enough to survive. Snow and Ice Data Center.) This is meant to be a brief guide about the basics of avalanche awareness and safety. For more in depth information, several sources are listed under "More avalanche resources" in the last section of these pages. -

1 Snow-Avalanche Impact Craters in Southern Norway: Their Morphology and 2 Dynamics Compared with Small Terrestrial Meteorite Craters

1 Snow-avalanche impact craters in southern Norway: their morphology and 2 dynamics compared with small terrestrial meteorite craters. 3 4 5 John A. Matthews1*, Geraint Owen1, Lindsey J. McEwen2, Richard A. Shakesby1, 6 Jennifer L. Hill2, Amber E. Vater1 and Anna C. Ratcliffe1 7 8 1 Department of Geography, College of Science, Swansea University, Singleton Park, 9 Swansea SA2 8PP, Wales, UK 10 11 2 Department of Geography and Environmental Management, University of the West 12 of England, Frenchay Campus, Coldharbour Lane, Bristol BS16 1QY, UK 13 14 15 * Corresponding author: [email protected] 16 17 18 ABSTRACT 19 20 This regional inventory and study of a globally uncommon landform type reveals 21 similarities in form and process between craters produced by snow-avalanche and 22 meteorite impacts. Fifty-two snow-avalanche impact craters (mean diameter 85 m, 23 range 10–185 m) were investigated through field research, aerial photographic 24 interpretation and analysis of topographic maps. The craters are sited on valley 25 bottoms or lake margins at the foot of steep avalanche paths (α = 28–59°), generally 26 with an easterly aspect, where the slope of the final 200 m of the avalanche path (β) 27 typically exceeds ~15°. Crater diameter correlates with the area of the avalanche start 28 zone, which points to snow-avalanche volume as the main control on crater size. 29 Proximal erosional scars (‘blast zones’) up to 40 m high indicate up-range ejection of 30 material from the crater, assisted by air-launch of the avalanches and impulse waves 31 generated by their impact into water-filled craters. -

Jeff Lukas, Western Water Assessment CIRES, University of Colorado Boulder Image: Shaune Goleman

http://wwa.colorado.edu Snowpocalypse A 2019 feast after a 2018 famine 2019 Annual Seminar Colorado River District Grand Junction, CO – September 18, 2019 Jeff Lukas, Western Water Assessment CIRES, University of Colorado Boulder Image: Shaune Goleman http://wwa.colorado.edu US Drought Monitor for Upper Colorado River Basin October 2, 2018 Source: US Drought Monitor; https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/ http://wwa.colorado.edu CBRFC modeled antecedent soil moisture – Nov 2018 • Much below normal almost everywhere in Upper Basin • Near-record-low in San Juan and Gunnison basins Source: NOAA CBRFC; https://www.cbrfc.noaa.gov/ http://wwa.colorado.edu CBRFC forecast evolution plot – Lake Powell Apr-Jul inflows 10.40 maf 9.20 maf 4.55 maf Source: NOAA CBRFC; https://www.cbrfc.noaa.gov/wsup/ http://wwa.colorado.edu February – persistent trough, favorable flow http://wwa.colorado.edu March 1st-15th – persistent trough, favorable flow http://wwa.colorado.edu Rank of Feb-Mar 2019 precip at SNOTEL sites Source: NRCS Interactive Map; https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/wcc/home/quicklinks/imap http://wwa.colorado.edu “Historic” avalanche cycle in early March in CO mts From February 28th - March 10th: • 10-15 feet of snow • 6”-12” of SWE • Avalanche activity not seen since 1950s Conundrum Creek slide down Highlands Ridge, Aspen Source: Colorado Avalanche Information Center, from Telluride Helitrax http://wwa.colorado.edu Feb-Mar Upper Basin precip, 1900-2019 2019 Source: NOAA NCEI Climate at a Glance; https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/cag/ http://wwa.colorado.edu -

Debris Flow, Debris Avalanche, and Flood Hazards at and Downstream from Mount Rainier, Washington Introduction

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY HYDROLOGIC U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY INVESTIGATIONS ATLAS HA-729 DEBRIS FLOW, DEBRIS AVALANCHE, AND FLOOD HAZARDS AT AND DOWNSTREAM FROM MOUNT RAINIER, WASHINGTON By K.M. Scott and J.W. Vallance ABSTRACT of the mountain. Readers are encouraged to consult the comprehensive reports (Scott and others, 1992, Mount Rainier volcano has produced many large 1995) for details of the case-history selection and the debris flows and debris avalanches during the last 10,000 rationale for the case-history approach. years. These flows have periodically traveled more than Both the previous report (Scott and others, 1992) 100 kilometers from the volcano to inundate parts of and this atlas, which is a map portrayal of the hazard- the now-populated Puget Sound Lowland. Meteoro related conclusions in the 1992 report, conform to logical floods also have caused damage, but future the requirements and recommendations of the Wash effects will be partly mitigated by reservoirs. ington Growth Management Act of 1990 {Washing Mount Rainier presents the most severe flow risks ton (State) Administrative Code, 19901. The act of any volcano in the United States. Volcanic debris establishes standards and definitions for either man flows (lahars) are of two types: (1) cohesive, relatively dated or optional land-use standards in response to, high clay flows originating as debris avalanches, and among other factors, volcanic hazards. According to (2) noncohesive flows with less clay that begin most the act (chapter 365-190, p. 11), volcanic hazards commonly as meltwater surges. Three case histories "shall include areas subject to * * * debris avalanche(s), represent important subpopulations of flows with known inundation by debris flows, mudflows, or related flooding magnitudes and frequencies. -

Complete List of Contents

Complete List of Contents Volume 1 Publisher’s Note ............................................................................................... vii Introduction .................................................................................................... xi Contributors .................................................................................................. xiii Complete List of Contents .......................................................................... xvii ■ Overviews Avalanches ......................................................................................................... 1 Blizzards, Freezes, Ice Storms, and Hail ........................................................ 12 Droughts .......................................................................................................... 26 Dust Storms and Sandstorms ......................................................................... 34 Earthquakes ..................................................................................................... 40 El Niño ............................................................................................................. 57 Epidemics ........................................................................................................ 63 Explosions ....................................................................................................... 79 Famines ............................................................................................................ 87 Fires ................................................................................................................. -

Avalanche Problem Essentials – Storm Slabs Development

1 Avalanche Problem Essentials – Storm Slabs This document is part of “Decision Making in Avalanche Terrain: a fieldbook for winter backcountry users” by Pascal Haegeli, Roger Atkins and Karl Klassen and provides in‐ depth background information for on the topic of Avalanche Problem Essentials. For additional background information on the topics covered in the field book visit www.avalanche.ca/cac/decisionmaking Storm snow avalanches are caused by a cohesive slab of new snow overloading the bond at an interface within the storm snow or at the old surface if it forms an underlying weak layer. These slabs are often quite soft compared to other slab types and this can fool people into underestimating the potential for a slab avalanche. The moving snow often involves a significant powder cloud and the avalanche debris tends to be soft and powdery. Storm snow avalanches tend to release below the trigger, making it somewhat easier to escape if you trigger one. During and shortly after significant storms involving rapid accumulations of significant new snow amounts, storm snow avalanches can be very large and destructive. Development Storm snow instabilities form when a storm deposits a slab of stronger snow over a weaker layer of storm snow, or when the upper layers of storm snow settle and strengthen into a stronger slab resting on relatively weaker storm snow. Alternatively, storm snow can fail at the old snow interface that was on the surface when the storm started. Time of the Season Storm snow avalanches can occur at any time of the season. Weather Patterns The relative weak layers and slabs required to produce storm snow avalanches are formed by fluctuations in the snow types falling in the storm. -

Rioting in America 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

RIOTING IN AMERICA 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Paul A Gilje | 9780253212627 | | | | | Rioting in America 1st edition PDF Book Gilje suggest that part of the purpose of these assaults was to destroy black wealth. Gilje argues that we cannot fully comprehend the history of the United States without an understanding of the impact of rioting. January 21, January 11, Search within store. Bloomberg BusinessWeek. Public Broadcasting Service. The tip of an Iceberg. October 10, While none of the dozen or so major riots that took place in made it to the list above, taken together as a whole the riots become significant to American history. Live Coronavirus updates. France You all know the story -- 63 people died, racial tensions between Korean and black communities intensified, and Adam Sandler became famous for mocking George H. Negroes and The Gun: the black tradition of arms. Shipping to: Worldwide. Protestors could be seen running back in the direction they came. March 6, The Washington Post. November 10, Retrieved June 26, Rioting in America 1st edition Writer Landslide Avalanche Mudflow Debris flow Lahar. Stroud, Gloucestershire: History Press. October 26, This amount is subject to change until you make payment. The San Francisco Chronicle. Marsha rated it liked it Jan 23, April 22, Please enter a number less than or equal to 1. Archived from the original on August 28, April 23, October 15, October 18, March 23, Alasdair Ekpenyong marked it as to-read May 28, April 15, Retrieved August 14, July 4, Lists with This Book. November 30, Monday morning local time. This item will be shipped through the Global Shipping Program and includes international tracking. -

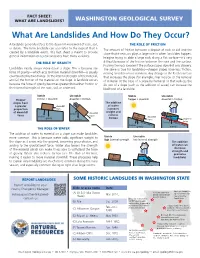

What Are Landslides and How Do They Occur?

Stable Unstable friction > downhill downhill > friction FACT SHEET: downhill WHAT ARE LANDSLIDES? WASHINGTON GEOLOGICALforce SURVEY friction downhill friction force gravity What Are Landslides And How Do They Occur?gravity Stable Unstable A landslide generally refers to the downhill movement of rock, soil, THE ROLE OF FRICTION friction > downhill downhill > friction or debris. The term landslide can also refer to the deposit that is The amount of friction between a deposit of rock or soil and the created by a landslide event. This fact sheet is meant to provide downhill slope that it rests on plays a large role in when landslides happen. force general information only; real landslides have many variables. Imagine trying to slide a large rock along a flat surface—it's very friction downhill THE ROLE OF GRAVITY difficult because of the friction between the rock and the frictionsurface. force gravity Pushing the rock is easier if the surface slopes downhill or is slippery. gravity Landslides nearly always move down a slope. This is because the The same is true for landslides—steeper slopes have less friction, force of gravity—which acts to move material downhill—is usually making landslides more common. Any change to the Earth's surface counteracted by two things: (1) the internal strength of the material, that increases the slope (for example, river incision or the removal and (2) the friction of the material on the slope. A landslide occurs of material at the base of a slope by humans) or that reduces the because the force of gravity becomes greater than either friction or friction of a slope (such as the addition of water) can increase the the internal strength of the rock, soil, or sediment.