Meeting Notice and Agenda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ACRP 03-31 Bibliography Last Update: June 15, 2016

ACRP 03-31 Bibliography Last Update: June 15, 2016 Contents Air Cargo ....................................................................................................................................................... 2 Air Service ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 Economic....................................................................................................................................................... 9 Environmental ............................................................................................................................................. 13 Finance ........................................................................................................................................................ 16 Land Use ..................................................................................................................................................... 18 Media Kit ..................................................................................................................................................... 19 Noise ........................................................................................................................................................... 21 Role of the Airport ....................................................................................................................................... 23 ACRP 03-31: Resources Bibliography Page -

Colonización, Resistencia Y Mestizaje En Las Américas (Siglos Xvi-Xx)

COLONIZACIÓN, RESISTENCIA Y MESTIZAJE EN LAS AMÉRICAS (SIGLOS XVI-XX) Guillaume Boccara (Editor) COLONIZACIÓN, RESISTENCIA Y MESTIZAJE EN LAS AMÉRICAS (SIGLOS XVI-XX) IFEA (Lima - Perú) Ediciones Abya-Yala (Quito - Ecuador) 2002 COLONIZACIÓN, RESISTENCIA Y MESTIZAJE EN LAS AMÉRICAS (SIGLOS XVI-XX) Guillaume Boccara (editor) 1ra. Edición: Ediciones Abya-Yala Av. 12 de octubre 14-30 y Wilson Telfs.: 593-2 2 506-267 / 593-2 2 562-633 Fax: 593-2 2 506-255 / 593-2 2 506-267 E-mail: [email protected] Casilla 17-12-719 Quito-Ecuador • Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos IFEA Contralmirante Montero 141 Casilla 18-1217 Telfs: (551) 447 53 66 447 60 70 Fax: (511) 445 76 50 E-mail: [email protected] Lima 18-Perú ISBN: 9978-22-206-5 Diagramcación: Ediciones Abya-Yala Quito-Ecuador Diseño de portada: Raúl Yepez Impresión: Producciones digitales Abya-Yala Quito-Ecuador Impreso en Quito-Ecuador, febrero del 2002 Este libro corresponde al tomo 148 de la serie “Travaux de l’Institut Francais d’Etudes Andines (ISBN: 0768-424-X) INDICE Introducción Guillaume Boccara....................................................................................................................... 7 Primera parte COLONIZACIÓN, RESISTENCIA Y MESTIZAJE (EJEMPLOS AMERICANOS) I. Jonathan Hill & Susan Staats: Redelineando el curso de la historia: Estados euro-americanos y las culturas sin pueblos..................................................................................................................... 13 II. José Luis Martínez, Viviana Gallardo, & Nelson -

Journal of the Inter-American Foundation

Grassroots Development J ournal of the Inter-American Foundation The IAF in Argentina VOLUME 24 NUMBER 1 2003 GrassrootsGrassroots DevelopmentDevelopment 20022002 23/123/1cov1 cov1 The Inter-American Foundation (IAF), an independent agency of the United States government, was created in 1969 as an experimental foreign assistance program. The IAF works to promote equitable, responsive and participatory self-help development by awarding grants directly to organizations in Latin America and the Caribbean. It also enters into partnerships with public and private sector entities to mobilize local, national and international resources for grassroots development. The IAF’s operating budget consists of congressional Grassroots Development appropriations and funds derived through the Social Progress Trust Fund. Journal of the Inter-American Foundation Frank Yturria, Chair, Board of Directors Patricia Hill Williams, Vice Chair, Board of Directors Publication Editor: Paula Durbin David Valenzuela, IAF President Photo Editor: Mark Caicedo Foreign Language Editions: Leyda Appel Grassroots Development is published in English and Spanish by the IAF’s Office of External Affairs. It appears on the IAF’s Web site at www.iaf.gov in English, Editorial Assistant: Adam Warfield Spanish and Portuguese versions accessible in graphic or text format. Original Design and Printing: U.S. Government Printing Office material produced by the IAF and published in Grassroots Development is in the public domain and may be freely reproduced. Certain material in this journal, however, has been provided by other sources and might be copyrighted. Reproduction of such material may require prior permission from the copyright holder. The editor requests source acknowledgement and a copy of any repro- duction. -

University of California Santa Cruz What Makes Community Forestry Work? a Comparative Case Study in Michoacan and Oaxaca, Mexi

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ WHAT MAKES COMMUNITY FORESTRY WORK? A COMPARATIVE CASE STUDY IN MICHOACAN AND OAXACA, MEXICO A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY in ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES by James Barsimantov June 2009 The Dissertation of James Barsimantov is approved: Professor Alan Richards, Chair Professor Daniel Press Professor Greg Gilbert i ii Table of Contents James Barsimantov – Doctoral Dissertation List of Tables iv List of Figures viii Abstract x Acknowledgements xi Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Chapter 2: Research Design and Methodology 18 Chapter 3: Is Community Forestry Related to Reduced Deforestation? An Analysis of 43 Eight Mexican States Chapter 4: Does Vertical Integration Matter? Social and Ecological Outcomes of 60 Community Forestry Programs Chapter 5: Internal and External Influences: Why do some communities attain higher 106 levels of vertical integration? Chapter 6:Vicious and Virtuous Cycles and the Role of External Non-Government 122 Actors in Community Forestry in Oaxaca and Michoacan, Mexico Chapter 7: Land cover change and land tenure change in Mexico’s avocado region: 140 Can community forestry reduce incentives to deforest for high value crops? Concluding Remarks 155 Appendix 1: Field Tools 160 Appendix 2: A Theoretical Model of Deforestation with Community Forestry 168 Appendix 3: Ecological Measures - Forest Transects 176 Bibliography 194 iii List of Tables James Barsimantov – Doctoral Dissertation Chapter 2 Table 2.1. A Schematic Approach to Case Selection of Mexican Forestry 20 Communities Table 2.2. Number and Percent of Communities by Level of Vertical Integration in 21 Oaxaca and Michoacan Table 2.3. -

Securing Air Cargo: Industry Perspectives

SECURING AIR CARGO: INDUSTRY PERSPECTIVES HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON TRANSPORTATION AND PROTECTIVE SECURITY OF THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JULY 25, 2017 Serial No. 115–24 Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 27–978 PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 15 2010 14:37 Jan 25, 2018 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 H:\115TH CONGRESS\17TP0725\27978.TXT HEATH Congress.#13 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas, Chairman LAMAR SMITH, Texas BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi PETER T. KING, New York SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas MIKE ROGERS, Alabama JAMES R. LANGEVIN, Rhode Island JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina CEDRIC L. RICHMOND, Louisiana LOU BARLETTA, Pennsylvania WILLIAM R. KEATING, Massachusetts SCOTT PERRY, Pennsylvania DONALD M. PAYNE, JR., New Jersey JOHN KATKO, New York FILEMON VELA, Texas WILL HURD, Texas BONNIE WATSON COLEMAN, New Jersey MARTHA MCSALLY, Arizona KATHLEEN M. RICE, New York JOHN RATCLIFFE, Texas J. LUIS CORREA, California DANIEL M. DONOVAN, JR., New York VAL BUTLER DEMINGS, Florida MIKE GALLAGHER, Wisconsin NANETTE DIAZ BARRAGA´ N, California CLAY HIGGINS, Louisiana JOHN H. RUTHERFORD, Florida THOMAS A. GARRETT, JR., Virginia BRIAN K. FITZPATRICK, Pennsylvania RON ESTES, Kansas BRENDAN P. SHIELDS, Staff Director KATHLEEN CROOKS FLYNN, Deputy General Counsel MICHAEL S. -

Corpus Christ Tule Lake Ship Docks # 1 And

Valero Meraux Port Information and Terminal Regulations Manual Copyright – Valero Services, Inc. – all rights reserved Revision 1.0 November, 2020 PREFACE: VALERO MERAUX PORT INFORMATION AND TERMINAL REGULATIONS MANUAL .................... 6 CONTACT NUMBERS: ........................................................................................................................................ 7 PART A: COMMUNICATIONS .................................................................................................................. 9 A.1 TERMINAL OWNERSHIP .......................................................................................................................................... 9 A.2 COMMUNICATION PRE-ARRIVAL REQUIREMENT ......................................................................................................... 9 A.3 COMMUNICATION – NOMINATION COORDINATOR...................................................................................................... 9 A.4 TERMINAL SUPERVISOR .......................................................................................................................................... 9 A.5 TERMINAL OPERATIONS CENTER .............................................................................................................................. 9 A.6 LOCAL TIME ......................................................................................................................................................... 9 A.7 RECEIPT OF MANUAL ............................................................................................................................................ -

Basic Concepts of Maritime Transport and Its Present Status in Latin America and the Caribbean

or. iH"&b BASIC CONCEPTS OF MARITIME TRANSPORT AND ITS PRESENT STATUS IN LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN . ' ftp • ' . J§ WAC 'At 'li ''UWD te. , • • ^ > o UNITED NATIONS 1 fc r> » t 4 CR 15 n I" ti i CUADERNOS DE LA CEP AL BASIC CONCEPTS OF MARITIME TRANSPORT AND ITS PRESENT STATUS IN LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN UNITED NATIONS Santiago, Chile, 1987 LC/G.1426 September 1987 This study was prepared by Mr Tnmas Sepûlveda Whittle. Consultant to ECLAC's Transport and Communications Division. The opinions expressed here are the sole responsibility of the author, and do not necessarily coincide with those of the United Nations. Translated in Canada for official use by the Multilingual Translation Directorate, Trans- lation Bureau, Ottawa, from the Spanish original Los conceptos básicos del transporte marítimo y la situación de la actividad en América Latina. The English text was subse- quently revised and has been extensively updated to reflect the most recent statistics available. UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATIONS Sales No. E.86.II.G.11 ISSN 0252-2195 ISBN 92-1-121137-9 * « CONTENTS Page Summary 7 1. The importance of transport 10 2. The predominance of maritime transport 13 3. Factors affecting the shipping business 14 4. Ships 17 5. Cargo 24 6. Ports 26 7. Composition of the shipping industry 29 8. Shipping conferences 37 9. The Code of Conduct for Liner Conferences 40 10. The Consultation System 46 * 11. Conference freight rates 49 12. Transport conditions 54 13. Marine insurance 56 V 14. -

Texas Freight Mobility Plan Goals

FINAL January 25, 2016 www.MoveTexasFreight.com Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1-1 1.1 Texas Freight Transportation Overview ............................................................... 1-2 1.1.1 Economy ............................................................................................... 1-2 1.1.2 Population ............................................................................................ 1-3 1.1.3 Trade ..................................................................................................... 1-3 1.1.4 Energy Production and Development ................................................. 1-4 1.1.5 Rural Freight Transportation ............................................................... 1-4 1.1.6 Urban Freight Transportation .............................................................. 1-4 1.1.7 Multimodal Transportation System .................................................... 1-5 1.2 Purpose of the Freight Plan ................................................................................. 1-7 1.3 Organization of the Freight Plan .......................................................................... 1-8 2.0 Strategic Goals ........................................................................................................ 2-1 2.1 Establishment of Consistent Goals ..................................................................... 2-2 2.1.1 National Freight Goals ........................................................................ -

Protestantism in Oaxaca, 1920-1995 Kathleen Mcintyre

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 1-31-2013 Contested Spaces: Protestantism in Oaxaca, 1920-1995 Kathleen McIntyre Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds Recommended Citation McIntyre, Kathleen. "Contested Spaces: Protestantism in Oaxaca, 1920-1995." (2013). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds/ 54 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kathleen Mary McIntyre Candidate Department of History Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Linda Hall, Chairperson Manuel García y Griego Elizabeth Hutchison Cynthia Radding Les W. Field i CONTESTED SPACES: PROTESTANTISM IN OAXACA, 1920-1995 by KATHLEEN MARY MCINTYRE B.A., History and Hispanic Studies, Vassar College, 2001 M.A., Latin American Studies, University of New Mexico, 2005 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy History The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December, 2012 ii DEDICATION To my mother, Cassie Tuohy McIntyre, for always believing in me. Many thanks. Do mo mháthair dhílis, Cassie Tuohy McIntyre, a chreid ionamsa ó thús. Míle buíochas. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It truly takes a pueblo to complete a dissertation. I am indebted to a long list of individuals and institutions in the United States and Mexico for supporting me throughout my investigation of religious conflict in Oaxaca. -

"I Do Not Know How to Fulfill Those Demands": Rethinking Jesuit

“I Do Not Know How to Fulfill Those Demands”: Rethinking Jesuit Missionary Efforts in La Florida, 1566-1572 by Saber Gray A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts Department of Florida Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida St. Petersburg Major Professor: J. Michael Francis, Ph.D. Raymond Arsenault, Ph.D. Erica Heinsen-Roach, Ph.D. Date of Approval: June 30, 2014 Keywords: Society of Jesus, education, colleges, evangelization, Cuba Copyright © 2014, Saber Gray ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many generous people have made this work possible. Dr. J. Michael Francis, my advisor since 2007, gently nudged me into researching the Florida Jesuits and secured digital copies of Jesuit correspondence from the Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu in Rome. His guidance has been, and continues to be, invaluable. My committee members, Dr. Raymond Arsenault and Dr. Erica Heinsen-Roach, had infinite patience. Thank you so much. All three professors gave me the insight and confidence to push my thesis further than I would have on my own. William and Hazel Hough generously provided for two summer research trips to the Archivo General de Indias in Seville, Spain. Lastly, thank you to everyone, especially graduate students at USFSP, who have listened to me babble about Jesuits for so long. i TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ..................................................................................................................... ii Abstract ............................................................................................................................. -

Researching North America: Sir Humphrey Gilbert's 1583

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History History, Department of 5-2013 Researching North America: Sir Humphrey Gilbert’s 1583 Expedition and a Reexamination of Early Modern English Colonization in the North Atlantic World Nathan Probasco University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss Part of the European History Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the United States History Commons Probasco, Nathan, "Researching North America: Sir Humphrey Gilbert’s 1583 Expedition and a Reexamination of Early Modern English Colonization in the North Atlantic World" (2013). Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History. 56. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss/56 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Researching North America: Sir Humphrey Gilbert’s 1583 Expedition and a Reexamination of Early Modern English Colonization in the North Atlantic World by Nathan J. Probasco A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: History Under the Supervision of Professor Carole B. Levin Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2013 Researching North America: Sir Humphrey Gilbert’s 1583 Expedition and a Reexamination of Early Modern English Colonization in the North Atlantic World Nathan J. Probasco, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2013 Advisor: Carole B. -

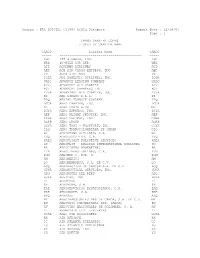

FAA DOT/TSC CY1997 ACAIS Database Report Date : 12/18/97 Page : 1

Source : FAA DOT/TSC CY1997 ACAIS Database Report Date : 12/18/97 Page : 1 CARGO CARRIER CODES LISTED BY CARRIER NAME CARCD Carrier Name CARCD ----- ------------------------------------------ ----- KHC 135 AIRWAYS, INC. KHC WRB 40-MILE AIR LTD. WRB ACD ACADEMY AIRLINES ACD AER ACE AIR CARGO EXPRESS, INC. AER VX ACES AIRLINES VX IQDA ADI DOMESTIC AIRLINES, INC. IQDA UALC ADVANCE LEASING COMPANY UALC ADV ADVANCED AIR CHARTER ADV ACI ADVANCED CHARTERS INT ACI YDVA ADVANTAGE AIR CHARTER, INC. YDVA EI AER LINGUS P.L.C. EI TPQ AERIAL TRANSIT COMPANY TPQ DGCA AERO CHARTER, INC. DGCA ML AERO COSTA RICA ML DJYA AERO EXPRESS, INC. DJYA AEF AERO FLIGHT SERVICE, INC. AEF GSHA AERO FREIGHT, INC. GSHA AGRP AERO GROUP AGRP CGYA AERO TAXI - ROCKFORD, INC. CGYA CLQ AERO TRANSCOLOMBIANA DE CARGA CLQ G3 AEROCHAGO AIRLINES, S.A. G3 EVQ AEROEJECUTIVO, C.A. EVQ XAES AEROFLIGHT EXECUTIVE SERVICES XAES SU AEROFLOT - RUSSIAN INTERNATIONAL AIRLINES SU AR AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS AR LTN AEROLINEAS LATINAS, C.A. LTN ROM AEROMAR C. POR. A. ROM AM AEROMEXICO AM QO AEROMEXPRESS, S.A. DE C.V. QO ACQ AERONAUTICA DE CANCUN S.A. DE C.V. ACQ HUKA AERONAUTICAL SERVICES, INC. HUKA ADQ AERONAVES DEL PERU ADQ HJKA AEROPAK, INC. HJKA PL AEROPERU PL 6P AEROPUMA, S.A. 6P EAE AEROSERVICIOS ECUATORIANOS, C.A. EAE KRE AEROSUCRE, S.A. KRE ASQ AEROSUR ASQ MY AEROTRANSPORTES MAS DE CARGA, S.A. DE C.V. MY ZU AEROVAIS COLOMBIANAS LTD. (ARCA) ZU AV AEROVIAS NACIONALES DE COLOMBIA, S. A. AV ZL AFFRETAIR LTD. (PRIVATE) ZL UCAL AGRO AIR ASSOCIATES UCAL RK AIR AFRIQUE RK CC AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC CC LU AIR ATLANTIC DOMINICANA LU AX AIR AURORA, INC.