Resistance to New Technology and Its Effects on Nuclear Power, Information Technology and Biotechnology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond Westworld

“We Don’t Know Exactly How They Work”: Making Sense of Technophobia in 1973 Westworld, Futureworld, and Beyond Westworld Stefano Bigliardi Al Akhawayn University in Ifrane - Morocco Abstract This article scrutinizes Michael Crichton’s movie Westworld (1973), its sequel Futureworld (1976), and the spin-off series Beyond Westworld (1980), as well as the critical literature that deals with them. I examine whether Crichton’s movie, its sequel, and the 1980s series contain and convey a consistent technophobic message according to the definition of “technophobia” advanced in Daniel Dinello’s 2005 monograph. I advance a proposal to develop further the concept of technophobia in order to offer a more satisfactory and unified interpretation of the narratives at stake. I connect technophobia and what I call de-theologized, epistemic hubris: the conclusion is that fearing technology is philosophically meaningful if one realizes that the limitations of technology are the consequence of its creation and usage on behalf of epistemically limited humanity (or artificial minds). Keywords: Westworld, Futureworld, Beyond Westworld, Michael Crichton, androids, technology, technophobia, Daniel Dinello, hubris. 1. Introduction The 2016 and 2018 HBO series Westworld by Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy has spawned renewed interest in the 1973 movie with the same title by Michael Crichton (1942-2008), its 1976 sequel Futureworld by Richard T. Heffron (1930-2007), and the short-lived 1980 MGM TV series Beyond Westworld. The movies and the series deal with androids used for recreational purposes and raise questions about technology and its risks. I aim at an as-yet unattempted comparative analysis taking the narratives at stake as technophobic tales: each one conveys a feeling of threat and fear related to technological beings and environments. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Electric Amateurs Literary encounters with computing technologies 1987-2001 Dorothy Butchard PhD in English Literature The University of Edinburgh 2015 DECLARATION is is to certify that the work contained within has been composed by me and is entirely my own work. No part of this thesis has been submitted for any other degree or professional quali"cation. ABSTRACT is thesis considers the portrayal of uncertain or amateur encounters with new technologies in the late twentieth century. Focusing on "ctional responses to the incipient technological and cultural changes wrought by the rise of the personal computer, I demonstrate how authors during this period drew on experiences of empowerment and uncertainty to convey the impact of a period of intense technological transition. From the increasing availability of word processing software in the 1980s to the exponential popularity of the “World Wide Web”, I explore how perceptions of an “information revolution” tended to emphasise the increasing speed, ease and expansiveness of global communications, while more doubtful commentators expressed anxieties about the pace and effects of technological change. -

Perpectives Battle Against Poliovirus in Pakistan

Perpectives Battle against poliovirus in Pakistan Kaneez Fatima1, Ishtiaq Qadri2 1IQ Institute of Infection and Immunity, Lahore, Pakistan 2King Fahd Medical Research Center, King Abdul Aziz University, Saudi Arabia Abstract On 22 Feb 2013, the Polio Monitoring Cell of Pakistan announced that the 2012-2013 polio campaign ended, and that 1.6 million children could not be vaccinated due to security concerns in several regions where polio workers had been killed. Those who could not be vaccinated included 50,000 children from the Federally Administrated Tribal Area (FATA), 150,000 form Khyber Pakhtoon Khao, 400,000 from a Quetta, 400,000 from Karachi, and a small number from the Rawalpindi District. These statistics are worrying, as several districts in the large metropolitan cities of Karachi and Quetta were also excluded. The fear of advanced medicine, ideas, or complex devices is a new phenomenon in many conservative and poor countries such as Pakistan, Afghanistan, Sudan, and Somalia. To safeguard the safety of the rest of the world, the failure in the implementation of WHO guidelines for vaccination must be regulated by the UN. There are a number of reasons for the phobias surrounding vaccination, but as technology continues to evolve at such a rapid rate, those with self-determined ideologies cannot cope with such advances. They become vocal to gain popularity and prevent the use of these technologies and medicine by creating and spreading rumors and propaganda of expediency. The struggle to vaccinate children is not easily understood by anyone living in the developed world. The irrational fear of vaccines and the lack of vaccination pose a serious global health risk and must be curbed through a wide variety of pro-vaccination media and religious campaigns. -

Technology, Labor, and Mechanized Bodies in Victorian Culture

Syracuse University SURFACE English - Dissertations College of Arts and Sciences 12-2012 The Body Machinic: Technology, Labor, and Mechanized Bodies in Victorian Culture Jessica Kuskey Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/eng_etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Kuskey, Jessica, "The Body Machinic: Technology, Labor, and Mechanized Bodies in Victorian Culture" (2012). English - Dissertations. 62. https://surface.syr.edu/eng_etd/62 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in English - Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT While recent scholarship focuses on the fluidity or dissolution of the boundary between body and machine, “The Body Machinic” historicizes the emergence of the categories of “human” and “mechanical” labor. Beginning with nineteenth-century debates about the mechanized labor process, these categories became defined in opposition to each other, providing the ideological foundation for a dichotomy that continues to structure thinking about our relation to technology. These perspectives are polarized into technophobic fears of dehumanization and machines “taking over,” or technological determinist celebrations of new technologies as improvements to human life, offering the tempting promise of maximizing human efficiency. “The Body Machinic” argues that both sides to this dichotomy function to mask the ways the apparent body-machine relation is always the product of human social relations that become embedded in the technologies of the labor process. Chapter 1 identifies the emergence of this dichotomy in the 1830s “Factory Question” debates: while critics of the factory system described workers as tools appended to monstrous, living machines, apologists claimed large-scale industrial machinery relieved human toil by replicating the laboring body in structure and function. -

Radical Environmentalism

Anyone who will read the anarchist and radical environmentalist journals will see that opposition to the industrial-technological system is widespread and growing. Theodore Kaczynski, aka the Unabomber Radical Environmentalism Green religion and the politics of radical environmentalism from Earth First! and the Earth Liberation Front to the Unabomber and anti-globalization resistance Department of Religion The University of Florida Spring 2017 Wednesdays, 4:05-7:05 p.m. Offered with both undergraduate & graduate sections: REL 3938, Section 1E77 RLG 6167, Section 1E76 Instructor: Dr./Prof. Bron Taylor Office: Anderson 121 Office Hours: Wednesdays, 1:30-3:00 p.m. (and by appointment) ! Course Gateways: Syllabus (The additional, direct access links, below, are also found in this syllabus.) Schedule of Readings and Assignments Bron Taylor’s Print History and Digital Archive of Earth First!, Wild Earth, Live Wild or Die, and Alarm Bibliography Documentary Readings WWW Sites Music Anyone who will read the anarchist and radical environmentalist journals will see that opposition to the industrial-technological system is widespread and growing Theodore Kaczynski, aka the Unabomber Course Description Radical Environmentalism Critical examination of the emergence . from Earth First! & the and social impacts of Radical Earth Liberation Front to Environmentalism, with special the Unabomber and the attention to its religious and moral anti-globalization resistance dimensions, and the ecological and political perceptions that undergird its Fall 2017 controversial strategies designed to Wednesdays 4:05-7:05p.m. arrest environmental degradation. Rel 3938 (undergraduate section) Rlg 6167 (graduate section) Course Overview and Objectives Instructor: Dr./Prof. Bron Taylor The University of Florida During the 1980s and much of the Office: Anderson 121; 1990s and beyond, thousands of Office Hours environmental activists were arrested W: 1:30-3:00 p.m. -

Transhumanism

T ranshumanism - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=T ranshum... Transhumanism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia See also: Outline of transhumanism Transhumanism is an international Part of Ideology series on intellectual and cultural movement supporting Transhumanism the use of science and technology to improve human mental and physical characteristics Ideologies and capacities. The movement regards aspects Abolitionism of the human condition, such as disability, Democratic transhumanism suffering, disease, aging, and involuntary Extropianism death as unnecessary and undesirable. Immortalism Transhumanists look to biotechnologies and Libertarian transhumanism other emerging technologies for these Postgenderism purposes. Dangers, as well as benefits, are Singularitarianism also of concern to the transhumanist Technogaianism [1] movement. Related articles The term "transhumanism" is symbolized by Transhumanism in fiction H+ or h+ and is often used as a synonym for Transhumanist art "human enhancement".[2] Although the first known use of the term dates from 1957, the Organizations contemporary meaning is a product of the 1980s when futurists in the United States Applied Foresight Network Alcor Life Extension Foundation began to organize what has since grown into American Cryonics Society the transhumanist movement. Transhumanist Cryonics Institute thinkers predict that human beings may Foresight Institute eventually be able to transform themselves Humanity+ into beings with such greatly expanded Immortality Institute abilities as to merit the label "posthuman".[1] Singularity Institute for Artificial Intelligence Transhumanism is therefore sometimes Transhumanism Portal · referred to as "posthumanism" or a form of transformational activism influenced by posthumanist ideals.[3] The transhumanist vision of a transformed future humanity has attracted many supporters and detractors from a wide range of perspectives. -

Christian Cyborgs: a Plea for a Moderate Transhumanism

Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers Volume 34 Issue 3 Article 5 7-1-2017 Christian Cyborgs: A Plea for a Moderate Transhumanism Benedikt Paul Göcke Follow this and additional works at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy Recommended Citation Göcke, Benedikt Paul (2017) "Christian Cyborgs: A Plea for a Moderate Transhumanism," Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers: Vol. 34 : Iss. 3 , Article 5. DOI: 10.5840/faithphil201773182 Available at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy/vol34/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers by an authorized editor of ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. CHRISTIAN CYBORGS: A PLEA FOR A MODERATE TRANSHUMANISM Benedikt Paul Göcke Should or shouldn’t Christians endorse the transhumanist agenda of chang- ing human nature in ways fitting to one’s needs? To answer this question, we first have to be clear on what precisely the thesis of transhumanism en- tails that we are going to evaluate. Once this point is clarified, I argue that Christians can in principle fully endorse the transhumanist agenda because there is nothing in Christian faith that is in contradiction to it. In fact, given certain plausible moral assumptions, Christians should endorse a moderate enhancement of human nature. I end with a brief case study that analyses the theological implications of the idea of immortal Christian cyborgs. I argue that the existence of Christian cyborgs who know no natural death has no impact on the Christian hope of immortality in the presence of God. -

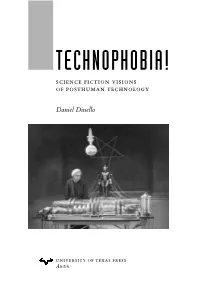

TECHNOPHOBIA! Science Fiction Visions of Posthuman Technology

TECHNOPHOBIA! science fiction visions of posthuman technology Daniel Dinello university of texas press Austin Frontispiece: Human under the domination of corporate science and autonomous technology (Metropolis, 1926. Courtesy Photofest). Copyright © 2005 by the University of Texas Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First edition, 2005 Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, University of Texas Press, P.O. Box 7819, Austin, TX 78713-7819. www.utexas.edu/utpress/about/bpermission.html The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ansi/niso z39.48-1992 (r1997) (Permanence of Paper). library of congress cataloging-in-publication data Dinello, Daniel Technophobia! : science fiction visions of posthuman technology / by Daniel Dinello. — 1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-292-70954-4 (cl. : alk. paper) — isbn 0-292-70986-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Science fiction—History and criticism. 2. Technology in literature. I. Title. pn3433.6.d56 2005 809.3'876209356—dc22 2005019190 NINE Technology Is a Virus machine plague virus horror: technophobia and the return of repressed flesh Technophiliacs want to escape from the body—that mor- tal hunk of animated meat. But even while devising the mode of their disembodiment, a tiny terror gnaws inside them—virus fear. The smallest form of life, viruses are parasites that live and reproduce by penetrating and commandeering the cell machinery of their hosts, often killing them and moving on to others. ‘‘As the means become available for the technology- creating species to manipulate the genetic code that gave rise to it,’’ says techno-prophet Ray Kurzweil, ‘‘...newvirusescanemergethroughacci- dent and/or hostile intention with potentially mortal consequences.’’1 The techno-religious vision of immortality represses horrific images of mutilated bodies and corrupted flesh that haunt our collective nightmares in the science fiction subgenre of virus horror. -

Are Technical Difficulties at the Supreme Court Causing a ''Disregard of Duty''?

92 JOURNAL OF LAW, TECHNOLOGY & THE INTERNET [VoL 3:1 ARE TECHNICAL DIFFICULTIES AT THE SUPREME COURT CAUSING A ''DISREGARD OF DUTY''? Mark Grabowski1 ABSTRACT Recent U.S. Supreme Court cases involving technology-related is sues indicate that several Justices are embarrassingly ignorant about computing and communication methods that many Americans take for granted. Indeed, some Justices admit they are behind the times. Yet, as members of the nation's highest court, they are increasingly asked to set legal precedents about these very technologies. The implications are profound for U.S. media law because, with the advent of the Digi tal Age, speech and expression have become intertwined with tech nology. The article argues that it is crucial for our most important decision-makers to keep pace with the times; otherwise, they may make poor legal decisions or avoid hearing important cases because they do not grasp the issues involved. In fact, such missteps may al ready be occurring. A few possible solutions are offered. INTRODUCTION If you are in America and not yet acquainted with cell phones, computers and the Internet, you must have spent the past decade under a rock-or be a member of the United States Supreme Court. Supreme Court Justices lately have displayed a startling level of ignorance about computing and communication methods that many Americans take for granted. Justice Clarence Thomas "generally characterizes the 1 Mark Grabowski is an assistant professor of communication at Adelphi University, where he teaches media law and new media. He also writes a column on legal affairs for AOL News, the third-most visited news website in the nation. -

Technology As Future Other: Exploring the Cinematic Cyborg As A

Technology as Future Other: Exploring the Cinematic Cyborg as a Crossroads of Xenophobia and Technophobia in the Terminator and RoboCop Series (1984-2014) C. A. (Tineke) Dijkstra s1021834 [email protected] Supervisor: Dr. E. (Liesbeth) Minnaard Second reader: Dr. E. J. (Evert) van Leeuwen Master Thesis Media Studies: Comparative Literature and Literary Theory Leiden University - Humanities Academic year 2014-2015 Front image: "Human 2.0: The Cyborg Revolution", courtesy of watchdocumentary.tv 1 Table of contents page Introduction (Theoretical Framework) 3 Xenophobia, Othering and Representation 7 Technophobia 10 Chapter 1: Early 1980s 13 The Terminator (1984) 13 RoboCop (1987) 18 In Conclusion 24 Chapter 2: Early 1990s 28 RoboCop 2 (1990) 28 Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) 34 RoboCop 3 (1993) 39 In Conclusion 43 Chapter 3: Post-9/11 48 Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines (2003) 49 Terminator Salvation (2009) 55 RoboCop (2014) 62 In Conclusion 67 Conclusion 69 Works Cited 72 2 Introduction (Theoretical Framework) This thesis examines the cinematic cyborg as a figure which embodies technophobic fears expressed in film. By exploring the cyborg's representation, I will show how its portrayal in film expresses these technophobic fears, which are, as I will show, interwoven with xenophobia. The cyborg is viewed here as a figure in which technophobia and xenophobia collide. I will examine the so-called preferred meaning expressed in my case studies, which are eight films featuring a cyborg protagonist released in a period of three decades. Moreover, I will compare these messages to see if and how the expressions of technophobia differ and whether they change over time. -

Teotwawki and Other Neoliberal Gods

JOSÉ MANUEL BUESO FERNÁNDEZ Integrante del colectivo artístico Declinación Magnética [email protected] Teotwawki and Other Neoliberal Gods A Reflection on End-of-the-World Politics vol 20 / Jun.2019 49-80 pp Recibido: 31-01-2019 - revisado 11-03-2019 - aceptado: 13-06-2019 © Copyright 2012: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Murcia. Murcia (España) ISSN edición impresa: 1889-979X. ISSN edición web (http://revistas.um.es/api): 1989-8452 Teotwawki and Other Neoliberal Gods: A Reflection on End-of-the-World Politics José Manuel Bueso TEOTWAWKI Y OTROS DIOSES NEOLIBERALES UNA REFLEXIÓN SOBRE LA POLÍTICA DEL FIN DEL MUNDO ABSTRACT Why is it easier to imagine the End of the World than the End of Capitalism? As a contribution to the (as yet) hypothetical discipline of Apocalyptology, which would be devoted to studying Capitalism’s multiple connections with the End of the World, this essay seeks to answer that question through a historical and critical analysis of what American Survivalists call Teotwawki as a meta- narrative framing for a variety of political discourses, ranging from Survivalism itself to the insurrectionary anarchism of the Invisible Committee, or the anarcho-primitivism of the Deep Ecology Movement and some accounts of the Anthropocene. Ever since the end of the 1970s, in a context where Capitalist Realism polices the boundaries of collective imaginaries, pre-empting any alternative to the Neoliberal order, end-of-the-world plots and tropes have been displacing end-of-capitalism narratives by redirecting the desire for radical social change towards the imagery of catastrophe and collapse and away from visions of revolution. -

Against Technology: from the Luddites to Neo-Luddism Steven E

Against Technology RT688X_FM.indd 1 3/6/06 10:01:49 AM RT688X_C000.indd 2 3/3/06 10:23:02 AM Against Technology From the Luddites to Neo-Luddism Steven E. Jones New York London Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business RT688X_FM.indd 2 3/6/06 10:01:49 AM RT688X_RT7867X_Discl.fm Page 1 Thursday, March 9, 2006 10:49 AM "All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace," in The Pill versus The Springhill Mine Disaster © 1968 by Richard Brautigan is reprinted with permission of Sarah Lazin Books. Published in 2006 by Published in Great Britain by Routledge Routledge Taylor & Francis Group Taylor & Francis Group 270 Madison Avenue 2 Park Square New York, NY 10016 Milton Park, Abingdon Oxon OX14 4RN © 2006 by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC Routledge is an imprint of Taylor & Francis Group Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 10987654321 International Standard Book Number-10: 0-415-97867-X (Hardcover) 0-415-97868-8 (Softcover) International Standard Book Number-13: 978-0-415-97867-5 (Hardcover) 978-0-415-97868-2 (Softcover) Library of Congress Card Number 2005031322 No part of this book may be reprinted, reproduced, transmitted, or utilized in any form by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying, microfilming, and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publishers. Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.