Jewish Comics; Or, Visualizing Current Jewish Narrative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

The Language of Narrative Drawing: a Close Reading of Contemporary Graphic Novels

The Language of Narrative Drawing: a close reading of contemporary graphic novels Abstract: The study offers an alternative analytical framework for thinking about the contemporary graphic novel as a dynamic area of visual art practice. Graphic narratives are placed within the broad, open-ended territory of investigative drawing, rather than restricted to a special category of literature, as is more usually the case. The analysis considers how narrative ideas and energies are carried across specific examples of work graphically. Using analogies taken from recent academic debate around translation, aspects of Performance Studies, and, finally, common categories borrowed from linguistic grammar, the discussion identifies subtle varieties of creative processing within a range of drawn stories. The study is practice-based in that the questions that it investigates were first provoked by the activity of drawing. It sustains a dominant interest in practice throughout, pursuing aspects of graphic processing as its primary focus. Chapter 1 applies recent ideas from Translation Studies to graphic narrative, arguing for a more expansive understanding of how process brings about creative evolutions and refines directing ideas. Chapter 2 considers the body as an area of core content for narrative drawing. A consideration of elements of Performance Studies stimulates a reconfiguration of the role of the figure in graphic stories, and selected artists are revisited for the physical qualities of their narrative strategies. Chapter 3 develops the grammatical concept of tense to provide a central analogy for analysing graphic language. The chapter adapts the idea of the graphic „confection‟ to the territory of drawing to offer a fresh system of analysis and a potential new tool for teaching. -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

Graphic Novels for Children and Teens

J/YA Graphic Novel Titles The 9/11 Report: A Graphic Adaptation Sid Jacobson Hill & Wang Gr. 9+ Age of Bronze, Volume 1: A Thousand Ships Eric Shanower Image Comics Gr. 9+ The Amazing “True” Story of a Teenage Single Mom Katherine Arnoldi Hyperion Gr. 9+ American Born Chinese Gene Yang First Second Gr. 7+ American Splendor Harvey Pekar Vertigo Gr. 10+ Amy Unbounded: Belondweg Blossoming Rachel Hartman Pug House Press Gr. 3+ The Arrival Shaun Tan A.A. Levine Gr. 6+ Astonishing X-Men Joss Whedon Marvel Gr. 9+ Astro City: Life in the Big City Kurt Busiek DC Comics Gr. 10+ Babymouse Holm, Jennifer Random House Children’s Gr. 1-5 Baby-Sitter’s Club Graphix (nos. 1-4) Ann M. Martin & Raina Telgemeier Scholastic Gr. 3-7 Barefoot Gen, Volume 1: A Cartoon Story of Hiroshima Keiji Nakazawa Last Gasp Gr. 9+ Beowulf (graphic adaptation of epic poem) Gareth Hinds Candlewick Press Gr. 7+ Berlin: City of Stones Berlin: City of Smoke Jason Lutes Drawn & Quarterly Gr. 9+ Blankets Craig Thompson Top Shelf Gr. 10+ Bluesman (vols. 1, 2, & 3) Rob Vollmar NBM Publishing Gr. 10+ Bone Jeff Smith Cartoon Books Gr. 3+ Breaking Up: a Fashion High graphic novel Aimee Friedman Graphix Gr. 5+ Buffy the Vampire Slayer (Season 8) Joss Whedon Dark Horse Gr. 7+ Castle Waiting Linda Medley Fantagraphics Gr. 5+ Chiggers Hope Larson Aladdin Mix Gr. 5-9 Cirque du Freak: the Manga Darren Shan Yen Press Gr. 7+ City of Light, City of Dark: A Comic Book Novel Avi Orchard Books Gr. -

7A Temporada 4.- El Rayo Mortal / Mr. Wonderful Daniel Clowes Gener 2014

7a Temporada 4.- El Rayo Mortal / Mr. Wonderful Daniel Clowes Gener 2014 Índex: Club de Lectura: L’autor: Daniel Clowes ......................................................................................................................................... 1 La seva obra .............................................................................................................................................................. 1 El Rayo Mortal / Daniel Clowes Random House Mondadori, 2013 El Rayo Mortal / Ressenya / Gerardo Vilches.......................................................................................... 2 El Rayo Mortal / Article / Juanjo Villalba................................................................................................... 3 Mr. Wonderful / Daniel Clowes Random House Mondadori, 2012 Mr. Wonderful / Ressenya / Gerardo Vilches........................................................................................... 5 Mr. Wonderful / Article / Antonio Fraguas ................................................................................................ 6 “Wilson es una respuesta triste a Mr. Wonderful ” / Entrevista / Noel Murray ........................................ 8 “El Rayo Mortal no trata de mostrar un mundo, sino insinuarlo” / Entrevista / Albert Fernández .. 9 Altres Recomanacions ....................................................................................................................................................... 10 Novetats de la tardor / Secció Còmics d’Adults / Bib. -

General Interest

GENERAL INTEREST GeneralInterest 4 FALL HIGHLIGHTS Art 60 ArtHistory 66 Art 72 Photography 88 Writings&GroupExhibitions 104 Architecture&Design 116 Journals&Annuals 124 MORE NEW BOOKS ON ART & CULTURE Art 130 Writings&GroupExhibitions 153 Photography 160 Architecture&Design 168 Catalogue Editor Thomas Evans Art Direction Stacy Wakefield Forte Image Production BacklistHighlights 170 Nicole Lee Index 175 Data Production Alexa Forosty Copy Writing Cameron Shaw Printing R.R. Donnelley Front cover image: Marcel Broodthaers,“Picture Alphabet,” used as material for the projection “ABC-ABC Image” (1974). Photo: Philippe De Gobert. From Marcel Broodthaers: Works and Collected Writings, published by Poligrafa. See page 62. Back cover image: Allan McCollum,“Visible Markers,” 1997–2002. Photo © Andrea Hopf. From Allan McCollum, published by JRP|Ringier. See page 84. Maurizio Cattelan and Pierpaolo Ferrari, “TP 35.” See Toilet Paper issue 2, page 127. GENERAL INTEREST THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART,NEW YORK De Kooning: A Retrospective Edited and with text by John Elderfield. Text by Jim Coddington, Jennifer Field, Delphine Huisinga, Susan Lake. Published in conjunction with the first large-scale, multi-medium, posthumous retrospective of Willem de Kooning’s career, this publication offers an unparalleled opportunity to appreciate the development of the artist’s work as it unfolded over nearly seven decades, beginning with his early academic works, made in Holland before he moved to the United States in 1926, and concluding with his final, sparely abstract paintings of the late 1980s. The volume presents approximately 200 paintings, sculptures, drawings and prints, covering the full diversity of de Kooning’s art and placing his many masterpieces in the context of a complex and fascinating pictorial practice. -

Sloane Drayson Knigge Comic Inventory (Without

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Number Donor Box # 1,000,000 DC One Million 80-Page Giant DC NA NA 1999 NA Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 A Moment of Silence Marvel Bill Jemas Mark Bagley 2002 1 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alex Ross Millennium Edition Wizard Various Various 1999 NA Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Open Space Marvel Comics Lawrence Watt-Evans Alex Ross 1999 0 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alf Marvel Comics Michael Gallagher Dave Manak 1990 33 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 1 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 2 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 3 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 4 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 2000 5 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 2000 6 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Aphrodite IX Top Cow Productions David Wohl and Dave Finch Dave Finch 2000 0 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 600 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 601 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 602 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Betty Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 603 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Betty Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 -

Supergirl: Volume 4 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SUPERGIRL: VOLUME 4 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mahmud A. Asrar,Michael Alan Nelson | 144 pages | 29 Jul 2014 | DC Comics | 9781401247003 | English | United States Supergirl: Volume 4 PDF Book Also, there are some moments where Kara's powers really don't make sense. Supergirl Vol 4 9 "Tempus Fugit" May, Supergirl Vol 4 12 "Cries in the Darkness" August, Matt rated it it was amazing Apr 06, However, I do prefer the more recent issues of the series, which send Kara-El Supergirl's Kryptonian name on a space quest with Krypto the Super-Dog and art by the always dependable Kevin Maguire. The one after that will be straight garbage that no effort whatsoever was put into. Jun 08, Mike marked it as series-in-progress. This issue tells the New 52 origin of Cyborg Superman. Supergirl Vol 4 54 "Statue of Limitations" March, Search books and authors. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. What's worse is how disjointed the story is. Supergirl Vol 4 51 "Making a Splash" December, It was just generic. Harley Quinn Vol. Supergirl Vol 4 47 "Before the Fall" August, Kara is dying of Kryptonite poisoning and has fled Earth. The issue that tracked Zor-El's conflict with Jor-El about how best to save Krypton from destruction was outstanding. Mesmer, one of. Slightly better than the last volume. Science Fiction. Supergirl has Kryptonite poisoning from her run in with H'el, so she takes off into space to 'die alone' Supergirl Vol 4 10 "Hidden Things" June, Enlarge cover. Jan 03, Fraser Sherman rated it it was ok Shelves: graphic-novels. -

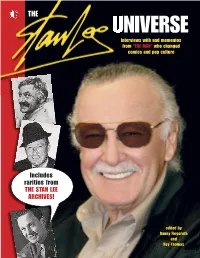

Includes Rarities from the STAN LEE ARCHIVES!

THE UNIVERSE Interviews with and mementos from “THE MAN” who changed comics and pop culture Includes rarities from THE STAN LEE ARCHIVES! edited by Danny Fingeroth and Roy Thomas CONTENTS About the material that makes up THE STAN LEE UNIVERSE Some of this book’s contents originally appeared in TwoMorrows’ Write Now! #18 and Alter Ego #74, as well as various other sources. This material has been redesigned and much of it is accompanied by different illustrations than when it first appeared. Some material is from Roy Thomas’s personal archives. Some was created especially for this book. Approximately one-third of the material in the SLU was found by Danny Fingeroth in June 2010 at the Stan Lee Collection (aka “ The Stan Lee Archives ”) of the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, and is material that has rarely, if ever, been seen by the general public. The transcriptions—done especially for this book—of audiotapes of 1960s radio programs featuring Stan with other notable personalities, should be of special interest to fans and scholars alike. INTRODUCTION A COMEBACK FOR COMIC BOOKS by Danny Fingeroth and Roy Thomas, editors ..................................5 1966 MidWest Magazine article by Roger Ebert ............71 CUB SCOUTS STRIP RATES EAGLE AWARD LEGEND MEETS LEGEND 1957 interview with Stan Lee and Joe Maneely, Stan interviewed in 1969 by Jud Hurd of from Editor & Publisher magazine, by James L. Collings ................7 Cartoonist PROfiles magazine ............................................................77 -

English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada

Drawing on the Margins of History: English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada by Kevin Ziegler A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2013 © Kevin Ziegler 2013 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This study analyzes the techniques that Canadian comics life writers develop to construct personal histories. I examine a broad selection of texts including graphic autobiography, biography, memoir, and diary in order to argue that writers and readers can, through these graphic narratives, engage with an eclectic and eccentric understanding of Canadian historical subjects. Contemporary Canadian comics are important for Canadian literature and life writing because they acknowledge the importance of contemporary urban and marginal subcultures and function as representations of people who occasionally experience economic scarcity. I focus on stories of “ordinary” people because their stories have often been excluded from accounts of Canadian public life and cultural history. Following the example of Barbara Godard, Heather Murray, and Roxanne Rimstead, I re- evaluate Canadian literatures by considering the importance of marginal literary products. Canadian comics authors rarely construct narratives about representative figures standing in place of and speaking for a broad community; instead, they create what Murray calls “history with a human face . the face of the daily, the ordinary” (“Literary History as Microhistory” 411). -

How Superman Developed Into a Jesus Figure

HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE CRISIS ON INFINITE TEXTS: HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE By ROBERT REVINGTON, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Robert Revington, September 2018 MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2018) Hamilton, Ontario, Religious Studies TITLE: Crisis on Infinite Texts: How Superman Developed into a Jesus Figure AUTHOR: Robert Revington, B.A., M.A (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Travis Kroeker NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 143 ii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies LAY ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. It argues that this connection was not integral to the character as he was originally created, but was imposed by later writers over time and mainly for cinematic adaptations. This thesis also tracks the history of how Christians and churches viewed Superman, as the film studios began to exploit marketing opportunities by comparing Superman and Jesus. This thesis uses the methodological framework of intertextuality to ground its treatment of the sources, but does not follow all of the assumptions of intertextual theorists. iii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. Superman was created in 1938, but the character developed significantly from his earliest incarnations.