Essays on Aristotle's Poetics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Levels of Homophobia

Levels of Homophobia Negative Positive Repulsion Pity Tolerance Acceptance Support Admiration Appreciation Nurturance Negative Levels: Repulsion: Homosexuality is seen as “a crime against nature.” Homosexual people are sick, crazy, sinful, immoral, wicket, etc. Anything is justified to change them, it: prison, hospitalization, from behavior therapy to shock treatment. Pity: Heterosexual chauvinism. Heterosexuality is more mature and certainly to be preferred. Any possibility of being straight should be reinforced and those who seem to be “born that way” should be pitied. Tolerance: Homosexuality is just a phase of adolescent development that many people go through and ‘grow out of’. Thus lesbians, gays and bisexuals are less mature than heterosexual people and should not be put in positions of authority because they are still working on adolescent behaviors. Acceptance: Still implies that there is something that must be accepted. Characterized by such statements as ‘you’re not gay to me, you’re just a person’. Denies the social and legal realities, while ignoring the pain of invisibility and the stress of closeted behavior. Positive Levels: Support: Work to safeguard the rights of LGBT people. May be uncomfortable themselves, but are aware of the social climate and irrational unfairness. Admiration: Acknowledges that being LGBT in our society takes strength. Such people are willing to truly look at themselves and work on their own homophobic attitudes. Appreciation: Values the diversity of people and sees LGBT people as a valid part of diversity. These people are willing to combat homophobia in themselves and others. Nurturance: Assumes that LGBT people are indispensable to society. They view all homosexual people with genuine affection and delight and are willing to be open and public advocates. -

Suffering, Pity and Friendship: an Aristotelian Reading of Book 24 of Homer’S Iliad Marjolein Oele University of San Francisco, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of San Francisco The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences 11-2010 Suffering, Pity and Friendship: An Aristotelian Reading of Book 24 of Homer’s Iliad Marjolein Oele University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.usfca.edu/phil Part of the Classics Commons, and the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Oele, Marjolein, "Suffering, Pity and Friendship: An Aristotelian Reading of Book 24 of Homer’s Iliad" (2010). Philosophy. Paper 17. http://repository.usfca.edu/phil/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Suffering, Pity and Friendship: An Aristotelian Reading of Book 24 of Homer’s Iliad Marjolein Oele University of San Francisco [email protected] Book 24 of Homer’s Iliad presents us with one of the most beautiful and chilling scenes of the epic: the scene where Achilles and Priam directly face one another at the point when the suffering (pathos) of each seems to have reached its pinnacle. Achilles’ suffering is centered on the loss of his best friend Patroclus, while the suffering of Priam – although long in the making due to the attack on his city and his family – has reached a new level of despair with the loss of his dearest son Hector. -

Resiliency and Character Strengths Among College Students

Resiliency and Character Strengths Among College Students Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Chung, Hsiu-feng Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 02/10/2021 04:26:47 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/195507 RESILIENCY AND CHARACTER STRENGTHS AMONG COLLEGE STUDENTS by Hsiu-feng Chung _________________________________ Copyright © Hsiu-feng Chung 2008 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATIONAL PSYCHOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2008 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Hsiu-feng Chung entitled Resiliency and Character Strengths Among College Students and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 04/01/08 Mary McCaslin, Ph. D. _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 04/01/08 Thomas Good, Ph. D. _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 04/01/08 Sheri Bauman, Ph. D. _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 04/01/08 Heidi Burross, Ph. D. Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

The Difference Between Empathy and Sympathy by Thoughtco., Adapted by Newsela Staff on 12.20.17 Word Count 829 Level 1010L

The difference between empathy and sympathy By ThoughtCo., adapted by Newsela staff on 12.20.17 Word Count 829 Level 1010L Image 1. A woman gives food to a homeless man in New York City. Photo by: Ed Yourdon/WIkimedia. Is that "empathy" or "sympathy" you're showing? These two words are often used interchangeably, but that is incorrect. Their difference is important. Sympathy is a simple expression of concern for another person's misfortune. Empathy, however, goes beyond sympathy. Empathy is the ability to actually feel what another person is feeling, like the saying "to walk a mile in their shoes." Taken to extremes, deep or extended feelings of empathy can actually be harmful to one's emotional health. Sympathy Sympathy is a feeling and expression of concern for someone, often accompanied by a wish for them to be happier or better off. An example of sympathy is feeling concerned after finding out someone has cancer and hoping the treatment goes well for him or her. In general, sympathy implies a deeper, more personal level of concern than pity. Pity is really just a simple expression of sorrow. However, sympathy does not imply that someone's feelings for another person are based on shared experiences or emotions. That is empathy. Empathy Empathy is the ability to recognize and share another person's emotions. Empathy requires the ability to recognize the suffering of another person from his or her point of view. It also means openly sharing another person's emotions, including painful distress. Empathy is often confused with sympathy, pity and compassion. -

Compassion (Karuṇā) and Pity (Anukampā) in Mahāyāna Sūtras

Compassion (Karuṇā) and Pity (Anukampā) in Mahāyāna Sūtras WATANABE Shogo It is a well-known fact that ideas of “devotion” and “compassion” can be seen at the roots of Indian thought. For example, in the bhakti movement of the itinerant poet-saints known as Alvars salvation is considered to result from interaction between the believer’s devotion (bhakti) to God and God’s blessing (anukampā) bestowed on the believer. The principle of shared feelings and shared suffering to be seen in this sharing of devotion closely matches the workings of compassion (karuṇā) and pity (anukampā) in Buddhism. The god Viṣṇu and the Buddha are both entities who bestow blessings and are compassionate (anukampaka), but etymologically speaking they are also “sympathetic.” Especially in the notions of compassion and pity to be seen in Mahāyāna Buddhism the idea of sympathy or empathy in the form of sharing suffering is clearly in evidence, and this is underpinned by a spirit grounded in a sense of equality with all beings. In this paper I wish to examine compassion and pity as seen in Mahāyāna sūtras, and by doing so I hope to show that the principle of shared feelings and shared suffering is a concept that ties in with the contemporary idea of coexistence, or living in harmony with others. 1. Defining Compassion (Removing Suffering and Bestowing Happiness) The Sino-Japanese equivalent of “compassion” is the two-character compound cibei (Jp. jihi) 慈悲, and I wish to begin by analyzing this term. (a) Ci / ji 慈 (maitrī “friendliness” < mitra “friend”) This signifies “benevolence” or “kindness,” bringing benefits and happiness to others. -

Pity and Courage in Commercial Sex Garofalo, Giulia

www.ssoar.info Pity and courage in commercial sex Garofalo, Giulia Postprint / Postprint Rezension / review Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: www.peerproject.eu Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Garofalo, G. (2008). Pity and courage in commercial sex. [Review of the book Sex at the margins: migration, labour markets and the rescue industry, by L. M. Agustín]. European Journal of Women's Studies, 15(4), 419-422. https:// doi.org/10.1177/13505068080150040902 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter dem "PEER Licence Agreement zur This document is made available under the "PEER Licence Verfügung" gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zum PEER-Projekt finden Agreement ". For more Information regarding the PEER-project Sie hier: http://www.peerproject.eu Gewährt wird ein nicht see: http://www.peerproject.eu This document is solely intended exklusives, nicht übertragbares, persönliches und beschränktes for your personal, non-commercial use.All of the copies of Recht auf Nutzung dieses Dokuments. Dieses Dokument this documents must retain all copyright information and other ist ausschließlich für den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen information regarding legal protection. You are not allowed to alter Gebrauch bestimmt. Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments this document in any way, to copy it for public or commercial müssen alle Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise purposes, to exhibit the document in public, to perform, distribute auf gesetzlichen Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses or otherwise use the document in public. Dokument nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated Sie dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke conditions of use. -

Radical Hope Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation By: Jonathan Lear

Radical Hope Ethics In The Face Of Cultural Devastation By: Jonathan Lear Chapter 3: Critique of Abysmal Reasoning Submitted by Paul Lussier ‘Recommended Readings’ for the Aspen/Yale Conference 2007 The following is an excerpt from: Jonathan Lear, Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation, Harvard University Press (2006), pp.118-154 1 Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation By: Jonathan Lear Chapter 3: Critique of Abysmal Reasoning Courage and Hope Thus far I have argued that Plenty Coups's dream tracked reality at two levels. First, it picked up the anxiety of the tribe and responded to it. Second, insofar as the tribe's anxiety was justified--that it was a response to a menacing yet uncertain future--the dream addressed this real-life challenge at one remove. But the case for imaginative excellence can be made stronger than that. At a time of radical historical change, the concept of courage will itself require new forms. This is the reality that needs to be faced--the call for concepts--and it would seem that if one were to face up to such a challenge well it would have to be done imaginatively. Courage, as a state of character, is constituted in part by certain ideals--ideals of what it is to live well, to live courageously. These ideals are alive in the community, but they also take hold in a courageous person's soul. As we saw in the preceding chapter, these ideals come to constitute a courageous person's ego-idea22 In traditional times, it was in terms of such an ideal that a courageous warrior would "face up to reality"-that is, decide what to do in the face of changing circumstances. -

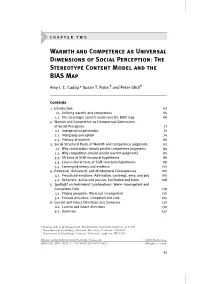

The Stereotype Content Model and the BIAS Map

CHAPTER TWO Warmth and Competence as Universal Dimensions of Social Perception: The Stereotype Content Model and the BIAS Map Amy J. C. Cuddy,* Susan T. Fiske,† and Peter Glick‡ Contents 1. Introduction 62 1.1. Defining warmth and competence 65 1.2. The stereotype content model and the BIAS map 66 2. Warmth and Competence as Fundamental Dimensions of Social Perception 71 2.1. Interpersonal perception 71 2.2. Intergroup perception 74 2.3. Primacy of warmth 89 3. Social Structural Roots of Warmth and Competence Judgments 93 3.1. Why social status should predict competence judgments 94 3.2. Why competition should predict warmth judgments 95 3.3. US tests of SCM structural hypotheses 96 3.4. Cross-cultural tests of SCM structural hypotheses 99 3.5. Converging theory and evidence 101 4. Emotional, Behavioral, and Attributional Consequences 102 4.1. Prejudiced emotions: Admiration, contempt, envy, and pity 102 4.2. Behaviors: Active and passive, facilitation and harm 108 5. Spotlight on Ambivalent Combinations: Warm–Incompetent and Competent–Cold 119 5.1. Pitying prejudice: Warm but incompetent 120 5.2. Envious prejudice: Competent but cold 125 6. Current and Future Directions and Summary 130 6.1. Current and future directions 130 6.2. Summary 137 * Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208 { Department of Psychology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08540 { Department of Psychology, Lawrence University, Appleton, WI 54912 Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Volume 40 # 2008 Elsevier Inc. ISSN 0065-2601, DOI: 10.1016/S0065-2601(07)00002-0 All rights reserved. 61 62 Amy J. C. -

Aristotle and Aquinas on Indignation: from Nemesis to Theodicy

Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers Volume 8 Issue 1 Article 6 1-1-1991 Aristotle and Aquinas on Indignation: From Nemesis to Theodicy Gayne Nerney Follow this and additional works at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy Recommended Citation Nerney, Gayne (1991) "Aristotle and Aquinas on Indignation: From Nemesis to Theodicy," Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers: Vol. 8 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. DOI: 10.5840/faithphil19918111 Available at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy/vol8/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers by an authorized editor of ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. ARISTOTLE AND AQUINAS ON INDIGNATION: FROM NEMESIS TO THEODICY Gayne Nerney The intention of this essay is to examine the accounts of indignation in the philosophical psychologies of Aristotle and Aquinas, and, in particular, Aquinas's criticism of Aristotle's evaluation of the ethical significance of this emotion. It is argued that Aquinas holds the truth concerning the nature of indignation not to be obtainable on the grounds of theological neutrality. The reason for this is that the philosophical account of indignation calls for a forthrightly theistic reflection on the ultimate meaning of this emotion. Thus, the account of nemesis within philosophical psychology finds its completion only in theodicy. The paper concludes with a reflection on the criticism that Aquinas's devaluation of indignation could undercut the emotional basis of the virtue of justice. -

Scientific Contribution Catharsis and Moral Therapy II: an Aristotelian Account

Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy (2006) 9:141–153 Ó Springer 2006 DOI 10.1007/s11019-005-8319-1 Scientific Contribution Catharsis and moral therapy II: An Aristotelian account Jan Helge Solbakk Section for Medical Ethics, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo, 1130, Blindern, NO-0318, Oslo, Norway (Phone: +47- 22844641; Fax: +47-22850590; E-mail: [email protected]) Abstract. This article aims at analysing Aristotle’s poetic conception of catharsis to assess whether it may be of help in enlightening the particular didactic challenges involved when training medical students to cope morally with complex or tragic situations of medical decision-making. A further aim of this investigation is to show that Aristotle’s criteria for distinguishing between history and tragedy may be employed to reshape authentic stories of sickness into tragic stories of sickness. Furthermore, the didactic potentials of tragic stories of sickness will be tried out. The ultimate aim is to investigate whether the possibilities of developing a therapeutic conception of medical ethics researched in a previous article on catharsis and moral therapy in Plato may be strengthened through the hermeneutics of the Aristotelian conception of tragic catharsis. Key words: Catharsis, emotions, error, fallibility, fear, guilt, hamartia, therapy, tragedy Introduction in their teaching, i.e. on conceptual clarifications and purifications, on methodological case study The present article aims at investigating Aristotle’s analyses and on rational strategies and theories for controversial treatment of the notion of tragic resolving moral dilemmas, while neglecting the catharsis in the Poetics. There are three reasons for cathartic role that pity, fear and other painful limiting the scope to the Poetics. -

Motivational and Behavioral Expressions of Schadenfreude 1

Motivational and Behavioral Expressions of Schadenfreude 1 Running Head: Motivational and Behavioral Expressions of Schadenfreude Motivational and Behavioral Expressions of Schadenfreude among Undergraduates Elana P. Kleinman Thesis completed in partial fulfillment of the Honors Program in the Psychological Sciences Under the Direction of Dr. Leslie Kirby and Dr. Craig Smith Vanderbilt University April 2017 Motivational and Behavioral Expressions of Schadenfreude 1 Abstract Schadenfreude, the pleasure that results from another person’s misfortune, is an interesting topic within emotion research. However, there has been limited research regarding whether cultural tendencies influence the motivational urges, action tendencies, and enacted behaviors of schadenfreude. In order to find out whether culture and language influence the motivational and behavioral expressions of schadenfreude, participants (N=146) completed an online questionnaire in which they read a schadenfreude eliciting vignette and responded to a series of questions to assess their appraisals, emotions, thoughts, and action tendencies. In addition, participants filled out measures to assess their levels of individualism/collectivism and empathy. The vignettes followed a 2 (competitive, slapstick) x 2 (academic, social) x 3 (friend, stranger, disliked target) design in order to determine whether certain situations and/or targets elicited greater amounts of schadenfreude. Although the expected culture and language differences were not significant in predicting schadenfreude, we found that schadenfreude is influenced by the target, the situation, and the individual’s level of empathy. In addition, we found that the significant appraisals associated with schadenfreude were: relevance, congruence, outside factors, other accountability, and accommodation-focused coping potential. Motivational and Behavioral Expressions of Schadenfreude 2 When another person experiences misfortune, our reactions can take several forms. -

The Role of Personal Responsibility in Differentiating Shame from Guilt Jamie L

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library 8-2001 The meE rgence of the Capacity for Guilt in Preschoolers: The Role of Personal Responsibility in Differentiating Shame from Guilt Jamie L. Walter Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Child Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Walter, Jamie L., "The meE rgence of the Capacity for Guilt in Preschoolers: The Role of Personal Responsibility in Differentiating Shame from Guilt" (2001). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 70. http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/70 This Open-Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. THE EMERGENCE OF THE CAPACITY FOR GUILT IN PRESCHOOLERS: THE ROLE OF PERSONAL RESPONSIBILITY IN DIFFERENTIATING SHAME FROM GUILT BY Jamie L. Walter B.A. St. Mary's College of Maryland, 1992 A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in Psychology) The Graduate School The University of Maine August, 2001 Advisory Committee: Peter J. LaFreniere, Professor of Psychology, Advisor Janice Zeman, Associate Professor of Psychology Cynthia Erdley, Associate Professor of Psychology Joyce Benenson, Associate Professor of Counseling and Education Psychology Constance Peny, Professor of Education LIBRARY RIGHTS STATEMENT In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Maine, 1 agree that the Library shall make it fieely available for inspection. I hrther agree that permission for "fair use" copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Librarian.